CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Part V: Word-Formation 1 page

Word-formation is the process of coining new words from existing ones. Each word-formation process will result in the production of a specific type of word. If we know these word-forming devices, it will be easier to study the different types of words that exist in the English language. In the discussion of word-formation processes, we shall use the terms which were already introduced in the previous chapters, e.g., free forms which can stand alone; bound forms which cannot occur alone; stems which carry the basic meaning of the word; affixes which add the meaning to the word. If a stem consists of a single morpheme, it is called a root or a base. Roots constitute the core of words and carry their basic meaning. Stems and roots may be bound or free; however, affixes are always bound. Georgious Tserdanelis and Wai Yi Peggy Wong define the word-formation process as “the systematic relationships between roots and words derived from them, on the one hand, and between a word and its varied inflected, i.e., grammatical forms, on the other” (2004, p.156). The most important word-formation processes are derivation, compounding, conversion, blending, backformation, clipping, acronyms, and stress and tone placement.

5.1 Derivation/Affixation

Russian lexicologists approach the problem of derivation slightly differently. They term one of the word-formation processes as affixation,not derivation. The principle is the same, but the difference is in terms. We will use affixation and derivation interchangeably. Affixation is defined as “the formation of words by adding derivational affixes to different types of bases” (Ginzburg, Khidekel, Knyazeva, & Sankin, 1979, p. 114). Derivational affixes are divided into suffixes and prefixes. Prefixes are added to the beginning of bases, e.g., upload (up+load), and suffixes are added to the end of bases, e.g., employment (employ+ment). The formation of words with the help of prefixes is prefixation, while the process of formation of words with adding suffixes to the bases is suffixation.

Derivation, or affixation, creates a new word by changing the category or the meaning of the base to which it applies, e.g., teach (v)+ er (suffix) = teacher (n); beauty (n)+ful (suffix)=beautiful (adj). Derivation is a productive means of coining new words in English. There are more than sixty common derivational affixes, and there is no limit to their application.

Some English Derivational Affixes

| Affix | Change | Semantic Effect | Examples | |

| Suffixes | ||||

| -able | V ® A | able to be X’ed | readable | |

| -ation | V ® N | the result of X’ing | realization | |

| -er | V ® N | one who X’s | teacher | |

| -ing | V ® N V ® A | the act of X’ing in the process of X’ing | playing the sleeping girl | |

| -ion | V ® N | the result or act of X’ing | graduation | |

| -ive | V ® A | having the property of doing X | impressive | |

| -ment | V ® N | the act or result of X’ing | achievement | |

| -al | N ® A | pertaining to X | legal | |

| -ial | N ® A | pertaining to X | ||

| -ian | N ® N N ® A | pertaining to X | politician Russian | |

| -ic | N ® A | having the property of X | organic | |

| -ize | N ® V | put in X | hospitalize | |

| -less | N ® A | without X | jobless | |

| -ous | N ® A | the property of having or being X | curious | |

| -ate | A ® V | make X | activate | |

| -ity | A ® N | the result of being X | similarity | |

| -ize | A ® V | make X | modernize | |

| -ly | A ® Adv | in an X manner | silently | |

| -ness | A ® N | the state of being X | kindness | |

| Prefixes | ||||

| ex- | N ® N | former X | ex-wife | |

| in- | A ® A | not X | incompetent | |

| un- | A ® A V ® V | not X reverse X | unhappy undo | |

| re- | A ® A | X again | revisit | |

Each line in this table can be considered a word-formation rule, which predicts how new words may be formed. Thus, if there is a rule whereby the suffix –ment may be added to the verb achieve, resulting in a noun, denoting the act or result of achieving, then we can predict that if the suffix –ment is added to certain verbs, the result will be a new noun.

These rules may be used to analyze words as well as to form new words. Derivation can also create multiple levels of word structure. Although it may seem complex, correctional, unkindness, and organizational have structures consistent with the rules in the table (above).

Organizational

In the example with the word unkindness, the observation here is that the prefix un- readily combines with adjectives before it converts to a noun. We see from these examples that complex words have structures consisting of hierarchically organized constituents.

5.1.1 Types of Derivational Affixes

Derivational affixes are subdivided into two groups: class-changing and class-maintaining. Class-changing derivational affixes change the word class to which they are added. Thus, the verb achieve and the suffix –able create an adjective achievable. However, class-maintaining derivational affixes do not change the word class but change only the meaning of the word; for example, the noun adult and the suffix –hood create another noun adulthood, but now it is an abstract noun rather than a concrete noun. Class-changing affixes, when added to the stems, immediately change the class of the words, making them alternatively as a verb, a noun, an adverb, or an adjective. Therefore, derivational affixes determine or govern the word class of the stem. For instance, nouns may be derived from verbs or adjectives; adjectives may be derived from verbs and nouns; adverbs -- from either adjectives or nouns; and verbs may be derived from nouns or adjectives. English class-changing derivations are mostly suffixes. Noun-derivational affixes, which are also called nominalizers, are the following:

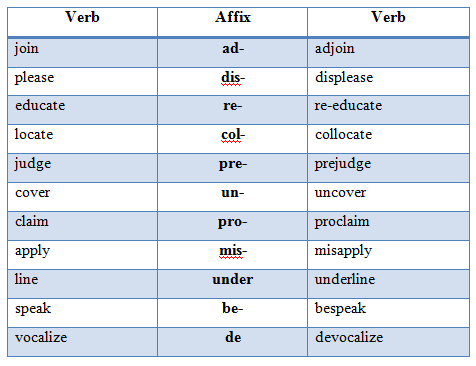

Verb-derivational affixes, also known as verbalizers, are used to coin verbs from other classes of words. Although verbs are used to form other classes of words, they are not readily formed from other parts of speech. The following derivational affixes build verbs from nouns and adjectives.

Adjective derivational affixes, or adjectivizers, are used to form adjectives mostly from the nouns and rarely from the verbs.

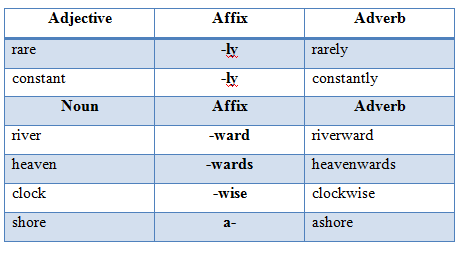

Adverb-derivational affixes, or adverbializers, are affixes which help form adverbs frequently from adjective and rarely from the nouns.

Class-maintaining derivations refer to those derivations which do not change the class of the stem to which they are added but change its meaning. Unlike class-changing derivations, which are mainly suffixes, class-maintaining derivations are prefixes and suffixes.

Noun patterns:

Verb patterns:

Adjective patterns:

English adverbs are not used to form words of other classes; therefore, there are no adverb patterns, as nouns, verbs, and nouns have.

5.2 Stress and Tone Placement

Sometimes a base can undergo a change in the placement of stress or tone to reflect a change in its category. There are some pairs of words in English in which a verb has a stress on the final syllable, while a corresponding noun is stressed on the first syllable.

5.3 Compounding

Compounding is a word-forming process which coins new words not by means of affixation but by combining two or more free morphemes. Compounding is a productive word-formation process. Actually, the parts of compound words may be only free morphemes, or the combination of free and bound morphemes. Compounds have more than one root, e.g., girlfriend, textbook, classmate, and others. Compounding is highly productive in the English language. It can be found in all the major lexical categories, such as nouns, adjectives, and verbs, but nouns are the most common type of compounds. The second element of a compound is usually the head, which carries the lexical meaning and determines the category of the entire word, whereas the first element only modifies the second element. For example, greenhouse is a noun just as house is. In addition, compounding can interact with derivation, e.g., abortion debate, in which the first word is derivation. Compounds consisting of two roots are the most numerous in the English language. Here are some examples of compounds, where nouns are initial elements: air (air-bed, air-brake, airbus, air-cell, air-conditioner, and others), arm (armchair), door (doorbell, doorjamb, and doormat), hand:(handball, handcar, and handcraft), eye: (eyeball, eyelash, eyeliner, eyesore, and eyewitness), heart (heartache, heartburn, and heartbreak), moon (moonbeam, moonboot, and moonlight). The following verbs are initial elements of compounds: pull (pullback and pullover), stand (standpatter and standpoint), swim (swimsuit and swimwear), and others. Adjectives as initial words include the following: big (bigfoot, bighead, and bighorn), brief (briefcase), short (shortbread, shortchange, and shorthand), high (highborn, highball, and highjack). Adverbs may also be as initial elements of compounds: down (downbeat, downburst, and downgrade), up (upbeat and upbound), and others.

There is a special type of compound which is formed by the combination of two bound morphemes. These types of compounds are called “neo-classical” (Jackson & Ze Amvela, 2007, p.95) compounds (bibliography, astronaut, pedophile, and xenophobia). New-classical compounding is a type of composition where the elements of a compound are not of native origin. They were mostly borrowed from classical languages such as Latin and Greek, e.g., bio-, auto-, tele-, -ology, and -phile. Such roots are considered bound roots. This creates a problem when distinguishing between neo-classical bound roots and affixes. Some examples of neo-classical compounds are the following: lexicology, morphology, semasiology, and others.

5.3.1 Classification of Compounds

As we discussed earlier, compounds consist of more than one root, but very often these roots do not belong to the same word class. Since the last element of a compound carries the lexical meaning, it also carries the grammatical meaning. As a general rule, the word class of the last element determines the class of the compound. Therefore, we classify compounds according to the word class: noun compounds, verb compounds, adjective compounds, adverb compounds, and special noun compounds.

Noun compounds are the ones whose first component belongs to any word class, e.g., a noun, an adjective, a verb, or an adverb, but the last element is a noun. Examples of noun compounds are the following:

N + N (modifier—head): doorbell, moonbeam, birdbrain, egghead, and eyewitness

Adj + N (modifier—head): blackboard, blackbird, highball, bluebonnet, and greenhouse

V + N (verb—object): daredevil, pickpocket, killjoy, and breakwater

Adv + N (not syntactic): afterthought

Verb compounds are the ones whose first component belongs to any word class, e.g., a noun, an adjective, a verb, or an adverb, but the last element is a verb. Examples of verb compounds are the following:

N + V (Object—Verb): brainwash, browbeat

V + V (co-ordinate): dropkick, freeze-dry

Adj + V (not syntactic): whitewash

Adv+ V (modifier—head): downgrade, undercut

Adjective compounds are the ones whose first component belongs to any word class, except a verb, but the last element is an adjective. Verbs do not combine with adjectives. Examples of adjective compounds are the following:

N + Adj (not syntactic): seasick, snow-white

Adj+Adj (co—ordinate): metallic-green, blue-green

Adv+Adj (modifier—head): nearsighted

Adverb compounds are not numerous. The combination of two adverbs constitutes an adverb compound: throughout, into.

The last group contains special noun compounds: V + Adv=Noun compound. This class of compounds is the only one which does not follow the general rule. In this case neither of the components determines the word class of the compound. The noun compound drive-in is formed from the verb drive and the adverb in.

5.3.2 Endocentric and Exocentric Compounds

Compounds express a wide range of meaning relationships. Leonard Bloomfield offers a classification based on the “relation of the compound as a whole to its members” (1935, p.235). He makes the distinction between “endocentric and exocentric compounds” (p.235). He borrows these terms from syntax and applies them to compounds. Most of the compounds are endocentric. A compound denotes a subtype of concept derived from its head, which is usually the last element of the compound; for example, steamboat means a boat driven by steam power. “Headedness is shown most clearly by hyponymy: the compound as a whole is a hyponym of its head” (Bauer, 1983). A compound word in which one member identifies the general class to which the meaning of the entire word belongs is called an endocentric compound (O’Grady, Archibald, Aronoff, & Rees-Miller, 2001, p.713). An exocentric compound does not have a head. A compound whose meaning does not follow from the meaning of its parts (e.g., redneck) is called an exocentric compound. Bloomfield argues that there are some compounds which can be endocentric and exocentric, depending on the meaning realized in the sentence. A good example is bittersweet. This compound is formed of two adjectives; therefore, it functions as an adjective endocentric compound, but it may not be a case if bittersweet is used to denote a poisonous Eurasian woody vine (Solanum dulcamara) or a North American poisonous woody vine (Celastrus scandens). In this instance, bittersweet functions as a noun; therefore, it is exocentric because “as a noun, it differs in grammatical function from the two adjective members” (Bloomfield, 1935, p. 135). Another example is bluebonnet. It is an endocentric compound if it denotes a wide flat round cap of blue wool formerly worn in Scotland. However, when it denotes the official Texas state flower, then it is exocentric. As these examples show, when a compound functions the same as the head member, it is still considered an exocentric compound because it is not a hyponym of its head. In the example of redneck, neck is the head component; however, in the modern usage, redneck is not a type of neck but a stereotyped person with rural, right-wing associations.

5.4 Reduplication

Reduplication is a process of forming new words by repeating the entire free morpheme (total reduplication) or a part of it (partial reduplication). It is not a productive means of forming new words in the English language, but it is common in other languages like Turkish. A few examples of reduplication in English are win-win, lose-lose, blah-blah, bye-bye, and goody-goody. The following examples illustrate partial reduplication: okey-dokey, zig-zag, chick-flick, roly-poly, walkie-talkie, knick-knack, and others. These combinations are used informally.

5.5 Conversion

Although conversion, the term first used by Henry Sweet (1898, p. 38), is one of the most productive means of coining new words in Modern English, scholars still argue whether this phenomenon should be studied within syntax, morphology, word-formation, or even semantics. Georgious Tserdanelis and Wai Yi Peggy Wong take a syntactic approach to conversion. They believe that conversion is the creation of new words “by shifting the part of speech to another part without changing the form of the word” (2004, p.430), contending that in Modern English, there is no distinction between parts of speech, i.e. between a noun and a verb, noun and adjective, and others. Thomas Pyles and John Algeo (1993, p.281) use the term ‘functional shift’ to refer to the same process to highlight that words are converted from one grammatical function to another without any change in form, e.g., paper (n)--paper (v). This functional approach to conversion cannot be justified and should be rejected as inadequate because one and the same word cannot simultaneously belong to different classes of words, or parts of speech. We defend a position that conversion is a word-forming process and should be studied within word-formation because conversion deals with forming new lexical units and perfectly fits the definition of word-formation as the process of coining new words from the existing ones.

The major kinds of conversion are noun ®verb, verb®noun, adjective ®noun, and adjective ® verb. For example:

Noun ®verb: bottle (n)—bottle (v), network (n)—network (v), father (n)—father (v), mother (n)—mother (v), eye (n)—eye (v), head (n)—head (v), paper (n)—paper (v), taxi (n)—taxi (v), and trash (n)—trash (v).

Verb®noun: call (v)—call (n), command (v)—command (n), impact (v)—impact (n), commute (v)—commute (n), blackmail (v)—blackmail (n), e-mail (v)—e-mail (n), and fax (v)— fax (n).

Adjective ® verb: better (adj)—better (v), savage (adj)—savage (v), and total (adj)— total (v).

Adjective ®noun: crazy (adj)—crazy (n) and poor (adj)—the poor (n). Such conversions are relatively rare. Some scholars believe that they are not conversions at all but substantivized adjectives.

Adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, interjections may act as bases for conversion, e.g. up (adv)—up (v) and down (adv)—down (v).

Although some scholars (Jackson & Ze Amvela, 2005) believe that conversion may occur within the same word class, e.g., walk (v) and walk (v) a dog, we do not consider them as conversions because they have different meanings of one and the same word, and these meanings are realized in the context. We do not recognize the class of marginal cases of conversion (Bauer, 1983), or partial cases of conversion. If any change is made in the structure, spelling, or pronunciation while new words are formed from the existing ones, we do not recognize them as conversions.

5.6 Blend(ing)

Blending is a word-forming process where a new lexeme is produced by combining the shortened forms of two or more words in such a way that their constituent parts are identifiable. The meaning is also a blend of two or more components. For example, harmolodic is a combination of harmonic and melodic. Other blends are comsat (communications + satellite), simulcast (simultaneous + broadcast), slurb (slum + suburban), druther (would + rather), and others. Additionally, refudiate, (refute + repudiate) was recently added to the New Oxford American Dictionary (2010). Some of these blends are coined for an occasion, as a political event; for example, Watergate is a hotel/office complex where a political scandal occurred, and later similar words were coined to denote certain types of scandals, e.g., Koreagate, oilgate, and computergate. Some of these combining forms come out of activity; for example, - thon means any long and uninterrupted activity, and it came from marathon. Later, new words were coined, such as begathons, danceathons, telethons, walkathons, workathons, phoneathons, and others. The exercise vogue produced the following blends: dancercise (dance + exercise), jazzercise (jazz + exercise), aerobicise (aerobic + exercise), aquacise (aqua + exercise), and others. Some combining forms appear out of the fever of fashion, such as –oholic and –aholic (a person addicted to or obsessed with), which generate the blends workaholic, shopaholic, chocoholic, melancholic, bookaholic, danceaholic, textaholic, and others. Some blends will disappear from use. Blends tend to be more frequent in informal style; however, they may be used in advertising and technical fields as well.

5.7 Eponyms

Eponymsare words created from names of (usually) famous people, and the words’ meanings relate to something specific about them or their experiences (Denham & Lobeck, 2010, pp. 196-197). An eponym is the term which stands for an ordinary common noun derived from a proper noun, the name of a person, or place. The first Hershey Bar was concocted in 1894 by a confectioner, Milton Hershey, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Two days later, a candy-maker, Leonard Hirschfield, and his daughter nicknamed Tootsie introduced the first paper-wrapped candy, the chewy Tootsie Roll (Panati, 1984, p.123). A sandwich was born when at 5 a.m., on August 6, 1762, John Montagu, fourth earl of Sandwich, felt hungry while gambling, so he ordered to bring him some cold thick-sliced roast beef between two pieces of toasted bread (Hendrickson, 2008, p. 728). Quisling (n) means ‘traitor,’ and quisle (v) is the back-formation from quisling, and it means ‘to betray one’s country.’ Major Quisling (1887-1945) earned his rank in the Norwegian army. He served as military attaché in Russia and Finland. Although the Norwegians considered him mentally unstable, he was able to form the National Unity Party, shortly before Hitler came to power in1933. Suppressing all opposition, he assumed King Haakon’s throne in the palace and drove around in a bulletproof limousine that was presented to him by Hitler. When the war was over, he was tried for treason, murder, and theft and found guilty on all accounts. He was shot by a firing squad in 1945 (Hendrickson, 2008, p. 691).

In figure skating, the term axel is used to denote a graceful jump consisting of one-and-half turns in the air. It is named after its inventor, the Norwegian skater, Axel Paulson, who perfected it in the late 19th century (p.47). Some other examples of eponyms are algorithm (named after al-Khowarizmi (circa 780-850), an Arabic mathematician); ampere (named after André Marié Ampére (1775-1836), the French physicist); atlas (Atlas was forced by Zeus to support the heavens upon his shoulders. It was taken from Greek mythology); July (the seventh month was named after Julius Caesar by Mark Anthony); August (the eighth month was named after Augustus Caesar (63 BCE-14 CE), the first Roman emperor); alexandrite (a grass-green chrysoberyl that shows a red color by transmitted or artificial light, named after Alexander I Russian emperor); bignonia (‘a plant,’ named after Abbé Jean- Paul Bignon (1662-1743, French royal librarian); bobby (‘a police officer,’ named after Sir Robert Peel, who organized the London police force); and boycott (named after Charles C. Boycott (1832-1897), English land agent in Ireland, who was ostracized for refusing to reduce rents) (Hendrickson, 2008).

5.8 Backformation

Backformation is coining a new word from an older word which is mistakenly taken as its derivative. It is “a process that creates a new word by removing a real or supposed affix from another word in a language” (O’Grady, Archibald, Aronoff, & Rees-Miller, 1993, p.127). For example, resurrect was formed from resurrection. Other backformations include accrete from accretion, adolesce from adolescence, attrit from attrition, babysit from babysitter, beg from beggar, bulldoze from bulldozer, choate from inchoate, commentate from commentator, enthuse from enthusiasm, evaluate from evaluation, haze from hazy, and others. Words ending in –or, ar, or -er are susceptible to backformation. Because such words as teacher, singer, and others are the result of suffixation, other words such as editor, burglar, peddler, respirator, and swindler are believed to be built the same way, resulting in creation of the verbs edit, burgle, peddle, respirate, and swindle. Many verbs are formed from abstract nouns ending in –ion: absciss from abscission, accrete from accretion, and ablute from ablution. The oldest backformation in American English is locate (from location), which came into being in the seventeenth century. After the Civil war, out of the word commutation a new word, commute, was coined to indicate a regular railroad travel to and from the city. Several other words such as housekeep, burgle, enthuse, donate, injunct, and jell were created. The British English also used backformation by changing an –ation noun to –ate verb: create from creation, deviate from deviation, delineate from delineation, placate from placation, and ruminate from rumination. Backformation continues to produce new words. Some are formed because of a real need, but some of them are just playful formations. These words are fully adopted into the language, and few persons who use them know their origin.

5.9 Clipping

In contradiction to the eighteenth century British English purism, the American English of the nineteenth century reveled in the process of clipping. Clipping is a process of word-formation which shortens a polysyllabic word by deleting one or more syllables, thus retaining only a part of the stem, e.g., lab (laboratory), bra (brassière), bus (omnibus), car (motorcar), and mob (mobile vulgus). Clipping is synonymous to shortening, so these terms will be used interchangeably.

Various classifications of shortened words have been offered. The generally accepted one is that based on the position of the clipped part. According to whether it is the final, the initial, or the middle part of the word that is cut off we distinguish initial clipping (aphaeresis), and medial clipping (syncope), final clipping (apocope).

Date: 2015-12-18; view: 4013

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Part III: Synchronic and Diachronic Approaches to the Structure of the English Vocabulary | | | Part V: Word-Formation 2 page |