CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Part III: Synchronic and Diachronic Approaches to the Structure of the English Vocabulary

3.1 Synchronic Approach to the Structure of the English Vocabulary

3.1.1 Common, Literary, and Colloquial layers

Synchronically, the structure of the English lexicon consists of common, literary, and colloquial layers. Leonhard Lipka further divides a literary layer into scientific, foreign, and archaic words. He includes technical, slang, vulgar, and dialectal words in the colloquial layer. The major part of the lexicon Lipka identifies as a common layer--lexemes, which are present in all the varieties of English. The following diagram provided by Lipka illustrates the structure of the English lexicon (2002, p.17). We believe this diagram should include neologisms, as well; they can appear in all the layers of the vocabulary: literary, common, and colloquial.

Common words are stylistically neutral, and their stylistic neutrality makes it possible to use them in all kinds of situations. The common vocabulary is the central group of the English lexicon, its historical foundation and living core. That is why words of this stratum show a considerably greater stability in comparison with words of the other strata, especially colloquial.

The literary layer of the English vocabulary is comprised of literary, scientific, and scholarly terms, foreign words, and archaisms. Besides general-literary (bookish) words, e.g., abdicate, harmony, aberration, accentuate, affinity, aggrandize, allege, antipathy, calamity, alacrity, equanimity, eschew, ingenuous, innocuous, etc., we may have various specific subgroups such as 1) terms or scientific words: gerocomy, genocide, nutrient, respiration, friction, hazard, laboratory, evaporation, vertebrate, and cyclone; 2) literary terms: accent, acrostic, allegory, allusion, antagonist, ballad, caesura, comedy, connotation, metaphor, metonymy, denotation, irony, rhyme, epiphany, oxymoron, parable, and paradox; 3) archaisms: thorp—‘village,’ whilom — ‘at times, formerly,’ aught — ‘anything, all, everything,’ and ere — ‘before.’ Sometimes a clipped form of a longer word supplants the latter altogether, turning it to an archaic word. Thus mob supplanted mobile vulgus ‘movable, or fickle, common people’; and omnibus, in the sense ‘motor vehicle for paying passengers,’ is almost as archaic as mobile vulgus, having been clipped to bus. Taxicab has completely replaced taximeter cabriolet. Bra has similarly supplanted brassiere (Algeo, 2010, p. 235); 4) foreign words: French: bon mot, camouflage, chauffeur, coupon, apropos, faux pas, and bouquet; Spanish: tamale, tortilla, jalapeno, pico de gallo, siesta, fiesta, lasso, burrito, taco, salsa, cilantro, guacamole, and enchilada; German: pretzel, strudel, dachshund, and kindergarten; Italian: confetti, crescendo, gondola, motto, pizza, regatta, lasagna, salami, and zucchini; Russian: babushka, borsch, samovar, sputnik, troika, and tundra; Hawaiian: aloha, hula, and wiki.

The colloquial layer includes technical, slang, jargon, dialectal, and vulgar words. “Slang words or phrases are typically very informal, and they are usually restricted to a particular group— typically teens and young adults— as a marker of in- group status” (Denham & Lobeck, 2010, p. 190). Most are not new words; they are usually existing words which acquired new meanings. Slang does not last long; however, the slang terms that stick around soon cease to be slang and join the common words stratum. Mob, hubbub, and rowdy were previously slang words. Some slang words like cool, nice, awesome, yeah right, whatever, ya, hot, and me too are used by a wide range of people. While some educated people do not use slang and view it unfavourably and hyperbolic, “slang is a feature of most languages and is an indicator of the ways in which language adapts for the purposes of those who use it” (Denham & Lobeck, 2010, p. 190).

Although Lipka does not differentiate between slang and jargon, we believe there are some differences between them. Jargon is not as informal as slang is, and jargon tends toward “specialized vocabulary associated with particular professions, trades, sports, occupations, games, and so on” (Denham & Lobeck, 2010, p. 190). Slang is used mostly by teens and young adults. Moreover, slang may not exist more than one generation, but jargon may travel from one generation to the other. Some medical jargon words are ailment, alleviate symptoms, allergen, benign, condition, dosage, edema, inflammation, inhibitor, lesion, syncope, intake, and vertigo. The following are university jargon words and expressions: academic advisor, term, semester, alumnus (alumni), assessment, campus, dissertation, elective, enrollment, finals, graduation, incomplete, independent student, learning outcomes, mentor, module, office hours, plagiarism, provost, sabbatical, seminar, tutor, and tutorial.

Slang is not the same as a style, or register, although some scholars claim they are. Bruce Rowe and Diane Levine (2012) argue, “The use of slang is another way that speakers indicate the informal register” (p. 214). By using slang, individuals indicate their social identity, and slang actually has never been accepted in formal language. Racial epithets are also slangs, and they are actually taboo slang, such as “wop for Italians who immigrated ‘without papers,’ wetback for Mexicans who illegally crossed the border by swimming across the Rio Grande, and slant eyes for Asians, who have an epicanthic fold in the eyelid” (Ibid, p. 214). Many people create their own slang words that are not identifiable by other people; however, slang words may be related to the whole generation that are identifiable by many people, e.g., jazz musicians of Harlem used the phrase cool cat to identify an individual who was a wonderful jazz musician. The hippies used the phrase far-out to express amazement or marked by a considerable departure from the conventional or traditional. Another expression hippies used is get high which means having some feelings after taking some drugs. This phrase still exists as slang.

Everyone has a different way of speaking in a formal or informal setting. Individuals shift registers easily and unconsciously. In the conversation with friends and family members, individuals use different vocabulary and tone than they would use during their teaching, lecturing, or conducting business. They never fail to switch from one register to another depending on a situation or a setting. According to Denham and Lobeck, register is the manner of speaking that depends on audience (e. g., formal versus informal) (2010, p. 190), and it is a speech or writing style adopted for a particular audience (Ibid, p. 342). Shifting registers, or styles, helps people maintain their social relationships. In a given situation, they may want to show their power, but in a different context, they may minimize it. Register differences can be shown in different ways. One is word choice when communicating in a formal or informal setting. Individuals will not use such words or phrases as gonna, ya’ll, wanna, and fixin’ during the job interview, but they may use them after the interview when they describe the interview process to their friends or family members. According to Frank Parker and Kathryn Riley, “when speaking or writing in a more formal register, our word choice may lean toward multisyllabic words rather than their shorter equivalents” (2010, p.180). Other ways of shifting registers are sentence structures, an accent, and tones. During the job interview, the interviewee may ask, “Which department will I be working in?” or “In which department will I be working?” The second example shows that the interviewee knows an appropriate formal style of communication. A registeris “the variety of language for a particular purpose” (Algeo & Pyles, 2010 p. 11), and the more different the circumstances are, the more registers we use to communicate our message. Registers are suitable to the situation, the level of formality, and the individual to whom we are speaking.

The word ‘technical’ is “a direct derivation from the Greek tekhne, an art, skill, or craft” (Murphy, 2011, p. 146). Technical terms are specialized vocabulary of various specialties. Some technical terms are binary, cache, encryption, domain, blacklist, buffer, defragment, keystroke, annealing, frit, grinder, and laminate.

Vulgar,ortaboo, words are “forbidden words or expressions interpreted as insulting or rude in a particular language” (Denham & Lobeck, 2010, p. 190). This term came from Latin vulgus, which means common people, so vulgar language is directly translated as the language of common people. Although vulgar words are forbidden, they have existed in the language for hundreds of years, and the list is extensive.

Dialectsare mutually intelligible varieties of a language that differ in systematic ways, but these language forms are understood by speakers of these varieties. “A dialect variety of a language has unique phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, and vocabulary and is spoken and understood by a particular group” (Denham & Lobeck, 2010, p. 514). Three types of dialects are identified such as regional, ethnic, and social. When people are separated from each other geographically, regional dialects develop. Dialectologists list three American regional dialects: Northern, Midland, and Southern. Ethnic dialects are characterized by ethnic groups living in those areas. “The linguistic characteristics of the people who settled there are the primary influence on that dialect, and the speech of most people in that area shares similar dialect features” (Denham & Lobeck, 2010, p. 410). Social dialects can reveal our educational or class status. The choice of a language variation and the speakers’ “attitudes about social class, politics, and religion all influence our linguistic choices” (Ibid, p.416).

3.1.2 Neologisms

Every year, new words appear in the English language. Some may be transient slang, but most of them become permanent members of the English word-stock. Some new words may appear because of cultural and technological changes, as in the case of iPad and iPhone: technological advances usually trigger a cascade of new words. “Coinings, or neologisms, are words that have been recently created” (Denham & Lobeck, 2010, p. 194). True neologisms are rare; usually new words are coined from old ones with the help of word-formation processes. Some true neologisms are bling (flashy jewellery worn, especially as an indication of wealth; expensive and ostentatious possessions), which is “hip-hop slang,” and googol coined by Milton Sirotta (the figure 1 followed by 100 zeros equals to 10100) (p.194). Tebowing (kneeling on one knee in prayer in a public place or being photographed doing this) was coined after Tim Tebow, a NFL player, who “started praying, even if everyone else around [him] was doing something completely different” (Introducing ‘Tebowing,’ 2011). Some new words are coined from place names. Examples are “oughterby, which is defined as someone we do not want to invite to a party but feel we should, and nottage, a word for the things we find a use for right after we have thrown them away” (Denham & Lobeck, 2010, p. 194). Metrosexual is a blending from metropolitan + -sexual, coined on the analogy of heterosexual. This neologism means ‘a usually urban heterosexual male given to enhancing his personal appearance by fastidious grooming, beauty treatments, and fashionable clothes’ (Merriam-Webster Online).

A professional group of linguists of the American Dialect Society (ADS) hold an annual competition “A Word of the Year” to showcase new words (Denham & Lobeck, 2010, p. 192). The table shows some new words which were coined between 2001 and 2010. Not all the words made ‘A Word of the Year,’ but they are still in circulation. The American Dialect Society (ADS) listed the following words in its website: http://www.americandialect.org/

| Year | Word/expression | Meaning |

| 2011 | occupy (v), (n) | referring to the Occupy protest movement |

| 2010 | app (n) hacktivism (n) -pad (n) Obamacare (n) Refudiate (v) | an application program for a computer or phone operating system. As in “there’s an app for that,” an advertising slogan for the iPhone. using computer hacking skills as a form of political or social activism combining form used by iPad and other tablet computers (ViewPad, WindPad, etc.). a pejorative term for the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. blend of refute and repudiate used by Sarah Palin on Twitter. It means ‘reject.’ |

| 2009 | tweet (n) (v) charging station (n) | (noun) a short message sent via the Twitter.com service, and (verb) to send such a message a place where electric cars recharge their batteries |

| 2008 | bailout (n) (v) shovel-ready (adj) | the rescue (n) (to rescue-v.) by the government of companies on the brink of failure, including large players in the banking industry used to describe infrastructure projects that can be started quickly when funds become available |

| 2007 | subprime (adj) elderproof (v) | an adjective used to describe a risky or less than ideal loan, mortgage, or investment to make something safe for the elderly to use. |

| 2006 | to pluto/be plutoed (v) flog (n) lactard (n) | to demote or devalue someone or something, as happened to the former planet Pluto when the General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union decided Pluto no longer met its definition of a planet. a fake blog created by a corporation to promote a product or a television show a person who is lactose-intolerant |

| 2005 | truthiness (n) | what one wishes to be the truth regardless of the facts |

| 2004 | red state, blue state, purple state (comp. noun) phish (v) fetch (adj) krunked mash-up (n) meet-up (n) orange revolution ( n) | together, a representation of the American political map to acquire passwords or other private information (of an individual, an account, a web site, etc.) via a digital ruse cool or stylish, from the movie Mean Girls cool, crazy a blend of two songs or albums into a single cohesive musical work. a local special interest meeting organized through a national website. the recent Ukrainian political crisis. |

| 2003 | embed (v) | to place a journalist with troops or a political campaign |

| 2002 | google (v) | to search the Web using the search engine Google for information on a person or thing |

| 2001 | facial profiling (n) | using video “faceprints” to identify terrorists and criminals |

3.2Diachronic Approach: Etymological Survey of the English Word-Stock

3.2.1 Definition of Etymology

Etymology [L. etymologia, < Gr, etymologia, <etymon (etymon-- an earlier form of a word in the same language or an ancestral language or a word in a foreign language that is the source of a particular loanword) and logia (doctrine, study)] of words is the study of the origins and history of the form and meaning of words. The Living Webster defines etymology as an “explanation of the origin and linguistic changes of a particular word and the derivation of a word” (1977, p.337). It is a historical evolution of lexical units.

The term etymology was actually created by the Stoics, a group of Greek philosophers and logicians, at the beginning of the fourth century (Jackson & Amvela, 2004, p.6). The Stoics noticed irregularities between the form and the content of certain words. “Since they were convinced that the language should be regularly related to its content, they undertook to discover the original forms called the ‘etyma’ (root) to establish the regular correspondence between language and reality” (Jackson & Amvela, 2004, p.6). The Stoics accurately perceived the disjunction between words and their forms, and from the etymological point of view, they saw the English vocabulary as anything but homogenous. The English word-stock is comprised of the native word-stock and the word-stock of borrowings from other languages, with a borrowed vocabulary much larger than the native stock of words.

3.2.2 English Lexemes of Native Origin

The term “native” typically denotes words of Anglo-Saxon origin brought to the British Isles from the continent in the 5th century by the Germanic tribes — the Angles, the Saxons, and the Jutes. Nevertheless, the term is often applied to words whose origin cannot be traced to any other languages. As mentioned above, numerically, the native word-stock is not large. The Anglo-Saxon stock of lexical items (lexemes) is estimated to make only “25% to 30% of the English vocabulary” (Eliseeva, 2003, p.40). A comprehensive dictionary of Anglo-Saxon falls short of “fifty thousand words” (Pei, 1967, p.91). If to consider that half of the spoken lexemes failed to find their way to the dictionary, it can be safely asserted that the native Anglo-Saxon language did not comprise more than one hundred thousand lexemes. Shakespeare’s vocabulary, which consisted mostly of native words, is believed to be the richest ever employed by any single man, and “it has been calculated to comprise 21,000 words” (Jespersen, 1938).

Robertson estimates that only “about twenty thousand words” are in circulation today, and if this estimate is correct, it brings us up to Shakespeare’s total. Of these words, “one-fifth, or about four thousand, are said to be of Anglo-Saxon origin, three-fifths, or about twelve thousand, of Latin, French, and Greek origin” (1954). However, this does not mean that foreign words predominate in the English language in daily discourse. In fact, the most frequently used words are native. These native words include most of the auxiliary and modal verbs (shall, will, must, can, may, and have), main verbs (live, die, come, go, do, make, give, take, eat, drink, work, play, walk, and run), nouns (home, house, room, window, door, floor, and roof), pronouns (I, you, he, my, his, and who), prepositions (to, in, of, out, on, and under), numerals (one, two, three, and four), and coordinating and subordinating conjunctions (and, but, till, and as). Words of Anglo-Saxon origin include the words, denoting the following: outward, visible parts of the body (head, hand, arm, back, finger, thumb, mouth, nose, ear, arm, leg, etc.), members of the family and closest relatives (father, mother, brother, son, wife, etc.), natural phenomena and planets (snow, rain, wind, sun, moon, star, etc.), animals (horse, cow, sheep, cat, etc.), qualities and properties (old, young, cold, hot, light, dark, and long), and common actions (do, make, go, come, see, hear, eat, etc.). Mario Pei (1967) states that if we go into literary usage, we find that “words of the Bible are ninety-four percent native, Shakespeare’s ninety percent, Tennyson’s eighty-eight percent, and Milton’s eighty-one percent” (p.93).

Most of the native lexemes have undergone great changes, for example, the process of combining roots with prefixes and suffixes or with other roots, the process of changes in the semantic structure of the words (polysemy), the process of spontaneous creation of words, and the process of analogy, where the words are coined in imitation of other words. The relative stability and semantic peculiarities of Anglo-Saxon words account for their great derivational potential. Most words of native origin make up large clusters of derived and compound words in the present-day language. As a case in point, the word ‘snow’ is the basis for the formation of the following words: snowball, snowbell, snowberry, snowbird, snowblink, snowblader, snowbound, snow-broth, snowbush, snow-cap, snowdrift, snowdrop, snowfall, snowfield, snowflake, snowman, snowmobile, snowpack, snowplough, snowshoe, snow shed, snow slide, snowy, and so on. Most Anglo-Saxon words are root-words; therefore, it is easy to coin new words.

New words have been created from Anglo-Saxon simple word-stems mainly by means of affixation, word-composition, and conversion. Such affixes of native origin as –er, -ness, -ing, -dom, -hood, -ship, -ful, -less, -y, -ish, -ly, -ish, -en, un-, and mis- make part of the patterns widely used to build numerous new words: happiness, childhood, childish, chilly, friendship, friendly, freedom, untrue, and misunderstand. Conversion is a common way to convert one part of speech to another using a form that represents one part of speech in the position of another without changing the form of the word at all; for example, one may use “The lights gleam in the night,” ‘gleam’ being a verb, and “I can see the gleam in the night,” ‘gleam’ being a noun. Compounding of words is creating new words that consist of at least two stems which occur in the language as free forms, e.g., horse-fly, pot-pie, rifle-range, horsewhip, bagpipe, policeman, etc. Although not numerous in Modern English, words of Anglo-Saxon origin must be considered very important due to their stability, specific semantic characteristics, great word-forming power, wide spheres of application, and high frequency value. The native element comprises not only the ancient Anglo-Saxon core but also words which appeared later as a result of word-formation, split polysemy, and other processes operative in English.

3.2.3 Borrowed, or Loan, Lexemes

When one language takes lexical units from other languages, we speak of borrowings or loan lexemes. The English language is an insatiable borrower. “Over 350 languages are on record as sources of its present-day vocabulary, and the locations of contact are found all over the world” (Crystal, 2003, p.126). Loan lexemes can be classified according to the following characteristics, either according to the source of borrowing or according to the degree of assimilation. According to the sources of borrowing, loan words are classified as borrowings of Celtic origin, Latin loans, Scandinavian borrowings, loans from German and Dutch, borrowings from French, Slavic, Hungarian, Turkish, and so on.

Borrowings of Celtic Origin

Celtic influence on the English language is minor. This may be explained by the fact that Celtic communities were destroyed or pushed back to the areas of Cornwall, Wales, Cumbria, and the Scottish borders. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that “at Andredesceaster or Pevensey a deadly struggle occurred between the native population and the newcomers and that not a single Briton was left alive” (Baugh & Cable, 1978, p.72). Apparently, large numbers of the defeated fled to the West. A whole cluster of Celtic place-names exist in the northeastern corner of Dorcetshire (p.73). It is also likely that Anglo-Saxons married Celtic women. At least there was some contact between these two peoples—Anglo-Saxons and the Celts. Some words survived into Modern English such as crag, cumb (deep valley), carr (rock), dunn (dun, grey), bald, down, glen, druid, bard, cradle, and others (The Living Webster, 1977). A few place-names are believed to be of Celtic origin. They include the river names such as Thames, Avon, Don, Exe, Usk, and Wye. Town names include Dover (water), Eccles (church), and Bray (hill) (Crystal, 2003, p. 8).

Borrowings from Latin

The first large influx of foreign borrowings into English came with the Latin of the missionaries, as well as through cultural and trade relations with the continent. Latin was the official language of the Christian church, and consequently the spread of Christianity was accompanied by a new period of Latin borrowings. These words were associated with church and religious rituals, e.g., priest (L. presbyter), monk (L. monachus), nun (L. nonna), and candle (L. candela). Scholarly terms were also borrowed, e.g., school (L. schola), scholar (L. scholar), and magister (L. magister). Some loans were associated with plants and animals, such as oak (L. quercus), pine (L.pinus), maple (L.acer), rose (L. rosa), lily (L. lilium), orchid (L. amerorchis rotundifolia), a white-tailed deer (L.odocoileus virginianus), raccoon (L.procyon lotor), and grey wolf (L.canis lupus). Others were associated with food, vessels, and household items, e.g., kitchen, cheese, kettle, cup, plum, wine, lettuce, chair, and knife (The Living Webster, 1977). Joseph Williams states that the proportion of Latin borrowings during this period would roughly be as follows: plants and animals, 30 percent; food, vessels, and household items, 20 percent; buildings and settlements, 12 percent; dress, 12 percent; military and legal, 9 percent; religious and scholarly, 3 percent; miscellaneous, 5 percent” (1975, p.57).

Scandinavian Borrowings

The next big linguistic invasion came as a result of the Viking raids on Britain, “which began in A.D. 787 and continued at intervals for some 200 years” (Crystal, 1995, p.25); however, the similarity between Old English and the language of Scandinavian invaders makes it sometimes very difficult to decide whether a given word in Modern English is native or borrowed. Many of the common words of the two languages are identical, and if there had been no Old English literature, it would be difficult to say whether a given word is of Scandinavian or native origin. As a result of the Scandinavian invasion, a large number of settlements with Danish names appeared in England, along with the personal names of Scandinavian origin. Sawyer (1962) counts 1,500 such place names, especially in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire. Over 600 end in suffix –by, the Scandinavian word for ‘town’ or ‘farm,’ e.g., Derby, Grimsby, Rugby, etc. Many place names end in –thorp (‘village’), e.g., Atlthorp, Astonthorpe; thwaite (‘clearing’), as in Braithwaite, Applethwaite; and toft (‘homestead’), as in Lowestoft, Eastoft, and Sandtoft (as cited in Crystal, 2003, p. 25). The Viking invasions led to an increase in personal names of Scandinavian origin. They express kinship or relationship to a parent or ancestor, e.g. Johnson, Robertson, Davidson, and they end in –son. In certain cases, there are reliable criteria by which words of Scandinavian origin can be recognized. One of the simplest ways to recognize words of Scandinavian origin is by the sound [sk], e.g., sky, skill, skin, ski, skirt. In Old English, sk was palatalized to sh (written sc) and [∫] in Modern English, whereas Scandinavian countries still retained the [sk] sound. The borrowed words from Scandinavian did not undergo palatalization and are still pronounced [sk]: skill, scrape, scrub, and bask. The Old English scyrte has become shirt, while the corresponding Old Norse (O.N.) form skyrta gives us skirt. In the same way, the retention of the hard pronunciation [k] and [g] in such words as kid, get, give, gild, egg is an indication of Scandinavian origin.

Loans from French

Toward the close of the Old English period, an event occurred which had a great impact on the English language. This event was the Norman Conquest, in 1066. The conquerors brought French to England, and French became the language of the ruling class. The Norman Conquest reduced the linguistic penetration of Scandinavian into one major area where the Danes were superior to the native English: “national administration, in which equable division of governmental units, fair taxation, strong criminal law, regulated commerce, and a high sense of personal honor predominated” (Nist, 1966, p.100). The Norman Conquest made French the official language in England. The following French words penetrated English: government, attorney, chancellor, country, court, crime, estate, judge, jury, noble, and royal; in the religious sphere: abbot, clergy, preach, sacrament, vestment, and many others. Some words designating English titles are of French origin: prince, duke, marquess, viscount, and baron, and their feminine equivalents, princess, duchess, marquise, viscount, and baroness, are also of French origin. Some military terms are of French origin: army, captain, corporal, lieutenant, sergeant, and soldier. French names were given to various animals when served up as food at Norman tables—beef, pork, veal, and mutton. Culinary processes were also named in French, for instance, boil, broil, fry, stew, and roast.

Later French borrowings are not assimilated as much as older borrowings, such as police, picnic, soup, and others. Later borrowings include aide-de-camp, amateur, ballet, baton, beau, bouillon, boulevard, brochure, brunette, bureau, café, camouflage, champagne, chaperon, chemisette, chiffonier, chute, cliché, commandant, communiqué, crochet, detour, foyer, fuselage, genre, hors d’oeuvre, impasse, invalid, liaison, limousine, lingerie, massage, matinee, menu, morale, morgue, naïve, negligee, plateau, première, protégé, rapport, repartee, repertoire, reservoir, restaurant, risqué, roué, rouge, saloon, souvenir, suéde, surveillance, tête-a-tête, and vis-à-vis.

Spanish Loanwords

English has taken words from Spanish as well. “Spanish words or Spanish transmissions came from the New World” (Pyles & Algeo, 1993, p. 300); they include such words as alligator, anchovy, armada, armadillo, avocado, barbecue, bolero, cannibal, cargo, castanet, chocolate, cigar, cocoa, cockroach, cork, corral, domino, embargo, flotilla, galleon, guitar, junta, maize, mescal, mantilla, mosquito, mulatto, negro, palmetto, peccadillo, plaza, potato, sherry, sombrero, tango, tomato, tornado, tortilla, vanilla, and others.

Borrowings from Italian

From another Romance language, Italian, English has acquired musical terms, such as duo, fugue, madrigal, violin, viola, allegro, largo, opera, piano, presto, recitative, solo, sonata, adagio, aria, cantata, concerto, contralto, staccato, tempo, and trio. Other loan words from Italian include artichoke, balcony, balloon, bandit, bravo, broccoli, cameo, canto, carnival, casino, dilettante, firm, fresco, lasagna, lava, macaroni, malaria, pizza, replica, scope, spaghetti, stanza, studio, umbrella, vendetta, and volcano. These borrowings are usually concentrated on the areas of arts and food but may be related to other areas, too.

Loans from Dutch and German

Dutch and German also contributed some words to English. The following Dutch words penetrated English: buoy, cruise, deck, and yacht. Much of the vernacular of geology and mineralogy is of German origin, such as cobalt, gneiss, lawine, loess, nickel, quartz, and zinc. Other words taken from German include hamburger, frankfurter, noodle, wienerwurst, and schnitzel. The vernacular of drinking includes lager, bock, and schnapps. Seminar and semester are ultimately Latin, but they entered American English by way of German.

Borrowings from Slavic, Hungarian, and Turkish

Very minor sources of the English vocabulary are of Slavic, Hungarian, and Turkish origins. The Slavic sable penetrated English through French. Astrakhan and mammoth came directly from Russian. Later, English assimilated such Russian words as kopeck, muzhik, ruble, steppe, tundra, troika, vodka, and sputnik. Goulash and paprika came from Hungarian. Turkish borrowings include khan, horde, and tulip. Tulip received its name from turban(d). It is believed to have looked like Turkish headgear (Pyles, 1964, pp.339-351; The Living Webster, 1977). Sometimes, words come to the English language indirectly. This is the case with the word coffee. Probably, even the Turkish are not aware that coffee actually originated in the Turkish language: kahveh (Turkish) > kahva (Arabic) > koffie > (Dutch) > coffee (English).

3.2.4 Classification of Borrowings according to the Degree of Assimilation

Loan lexemes are also classified according to the degree of their adaptation. Irina Arnold uses the term assimilation for this process “to denote a partial or total conformation to the phonetical, graphical, and morphological standards of the receiving language and its semantic system” (1986, p.255). She identifies the following three groups of loan words: completely-assimilated loans, partly- assimilated loans, and non-assimilated loans, which she terms barbarisms. She believes that most of the borrowed words, which penetrated the English language in earlier times, underwent changes and became completely assimilated loans. A good example is the French word sport. Without consulting an etymological dictionary, one would assume it is of native origin. According to Albert Baugh and Thomas Cable (1993, p.219), the adaptation of some loan words occurred by the simple process of cutting off the Latin ending, e.g., conjectural (L. conjectural-is), exclusion (L. exclusion-em), and exotic (L. exotic-us). Thus, the Latin ending –us in adjectives was changed to –ous ((L. conspicus>conspicuous) or was replaced by –al as in external (L. externus>external). Latin nouns ending in –tas were changed in English to –ty (brevitas>brevity).

The second group containing the partly assimilated loan lexemes can be divided into several subgroups:

a) Loan words partly assimilated semantically because they denote objects and notions peculiar to a particular country from which they come. They may denote foreign clothing: sari, sombrero; foreign titles and professions: shah, rajah, sheikh, and toreador; food and drinks: pilaf (Persian) and sherbet (Arabian).

b) Loan words partly assimilated grammatically, e.g., nouns borrowed from Latin or Greek retain their original plural forms: bacillus – bacilli, crisis – crises, and formula – formulae.

c) Loan words partly assimilated phonetically, e.g., machine, cartoon, police, bourgeois, confetti, incognito, macaroni, opera, sonata, tomato, and potato.

d) Loan words partly assimilated graphically: e.g., in Greek borrowings y appears in the middle of the word (symbol, synonym); ph is pronounced as [f] (phoneme, morpheme); ch is pronounced as [k] (chemistry, chaos); and ps is pronounced as [s] (psychology).

The third group of borrowings comprises the so-called barbarisms, i.e. words used by English speaking people in conversation or in writing, but these words retained their original forms, e.g., adios, ad libitum, tête-a-tête, and vis-à-vis.

3.2.5 Etymological Doublets and Triplets

Etymological doublets are two words of the same language which were derived from the same basic word by different routes. Some doublets are formed from different dialects, e.g., whole and hale are dialectal doublets. Whole came from Midland dialect, whereas hale came from Northern dialect. They differ to a certain degree in form, meaning, and current usage. The Latin words episcopus and discus penetrated Old English as bishop and dish. Later these words were borrowed again to create the words Episcopal and disc. Phonetic differences indicate that some French words were borrowed from different dialects—the Norman spoken in England (Anglo-Norman) and Central French (Standard French). It is easy to identify the doublets which came from Central French. Latin c [k] before a developed into ch [tò] in Central French but remained in Norman dialect. So, chapter came from Central French, which was originally adopted from Latin capitulum, a diminutive of caput; however, capital came from Norman dialect, which was also adopted from the same Latin word capitulum. The same explanation may be given to the doublets chattel and cattle. They both were borrowed by the French from Latin capitāle (possession, stock).

Scandinavian-English Doublets

| Old Norse | English from Scandinavian | English from Old English |

| skyrta | skirt | shirt |

| skip | skiff | ship |

| lan | loan | lend |

Latin-French Doublets

| Latin | English from Latin | English from French |

| abbreviare | abbreviate | abridge |

| aggravatus | aggravate | aggrieve |

| amicabilis | amicable | amiable |

| appretiare | appreciate | appraise |

The word appreciate was borrowed from Latin appretiare (to set a price to) in the1650s. The word appraise was borrowed from the stem of Old French aprisier in 1400. French borrowed this word from the Latin appretiare (to set a price to). The words gentle, genteel, and jaunty are borrowed from the French word gentil. Genteel and jaunty penetrated English in the seventeenth century. The same way chief penetrated English in the fourteenth century, and chef, in the nineteenth century (Pyles, 1964, p.336).

Etymological triplets are three words of the same language which were derived from the same basic word by different routes. Some examples are hospital (Latin) — hostel (Anglo-Norman) — hotel (Central French). All three words originated from the Latin word hospitāle. The verbs to capture (Latin) — to catch (Anglo-Norman) — to chase (Central French) have derived from Latin word captāre.

To sum up, although the English language has borrowed words from different languages and continues to do so, English remains English. What it has borrowed from other languages has given greater wealth to the English word-stock, not reducing the Englishness of the English language, but rather enriching it.

3.2.6 Folk Etymology

Etymological analysis requires a systematic research of the origin and development of lexemes or expressions that is done by scholars; however, not only researchers are concerned with the etymology of the language items, but laypersons are also curious about the make-up of words. People try to associate strange words with the ones they already know; therefore, every speaker is a kind of etymologist himself or herself. This trivial and amusing phenomenon is called folk etymology, or popular etymology, or false etymology. “In its simplest operations, folk etymology merely associates together words which resemble each other in sound and show a real or fancied similarity of meaning, but which are not at all related in their origin” (Greenough & Kittredge, 1967, p.145). This arises from ignorance of the true origin of these words. Some examples of folk etymology are Welsh rarebit (the original Welsh rabbit, ‘cheese on toast’) and sirloin (original surloin). Folk etymology not only affects the spelling of words and their associations, but “it [also] transforms the word, in whole or in part, so to bring it nearer to the word or words with which it is ignorantly thought to be connected” (p.147). Often, folk etymology affects borrowed words, e.g., sparrowgrass (L. asparagus), but it may affect native words as well, as in the example of sand-blind (original samblind). These examples show that folk etymology is based on people’s misunderstanding of certain words and their attempt to domesticate them so that they sound and spelled like the words in their own language. “Folk etymology—the naive misunderstanding of a more or less esoteric word that makes it into something more familiar and hence seems to give it a new etymology, false though it be—is a minor kind of blending” (Algeo, 2010, p. 241).

Part IV: The Word

4.1 Defining a Word

While everyone knows what a word is, defining one is surprisingly complex. Since the word is central to any language system, different disciplines including phonology, lexicology, syntax, morphology, psychology, and other branches of science bring their own particular questions to the notion of ‘word.’ Scholars in these fields characterize the notion of ‘word’ very specifically; therefore, their respective definitions show certain limitations. Within the scope of linguistics, the word has been defined syntactically, semantically, phonologically, and by combining various approaches. The semantic-phonological approach may be illustrated with Alan Gardiner’s definition: “A word is an articulate sound-symbol in its aspect of denoting something which is spoken about” (1922, p. 355). The eminent French linguist Paul Jules Antoine Meillet combines the semantic, phonological, and grammatical criteria: “A word is defined by the association of a particular meaning with a particular group of sounds capable of a particular grammatical employment” (1926, p.30). Edward Sapir takes into consideration the syntactic and semantic aspects when he calls the word “one of the smallest, completely satisfying bits of isolated meaning into which the sentence resolves itself” (1921, p.35). He also points out a very important characteristic of the word -- its indivisibility: “[A word] cannot be cut into without a disturbance of meaning, one or the other or both of the severed parts remaining as a helpless waif on our hands” (p. 35). We can illustrate this point with the help of the preposition about. If we divide it into two parts, a + bout, we receive two different words, an article a and a noun bout (a period of work or other activity). About and a bout do not share the same meaning. If we cut the word absorb into a and bsorb, we have an article a, but the severed part bsorb does not mean anything, thus “remaining as a helpless waif on our hands” (Sapir, 1921, p.35).

The American linguist Leonard Bloomfield is the first to suggest a formal definition of the word. He defines a word as a minimum free form. He identifies the basic unit of a structure as a morpheme (morphemes will be discussed later in the text). He states that a list of morphemes for a language constitutes the lexicon (1933, p.178). The notion lexicon is further developed by David Crystal. This term was borrowed from Greek in the early seventeenth century, which meant a dictionary containing a selection of words and meanings, arranged in an alphabetical order (Skeat, p. 260). The term itself comes from Greek lexis ‘word.’ The term lexicon has broadened its meaning, and within linguistics, it refers to the stock of meaningful units in a language. To study the lexicon of English means to study all aspects of the vocabulary of the language: words, idioms, prefixes, suffixes, meaning and meaning relations. Crystal differentiates between a word and a lexeme when he states, “A lexeme (or lexical item) is a unit of lexical meaning which exists regardless of any inflectional endings it may have or the number of words it may contain” (p.118). If we encounter a sentence with the words pixilating, pixilatates, and pixilated, we will disregard the endings of these words and look up the meaning of the lexeme pixilate (be somewhat unbalanced mentally or be drunk). For this reason, the headwords in a dictionary are all lexemes.

What counts as a word then? Howard Jackson and Etienne Zé Amvela (2007) define a word as an “uninterruptible unit of structure consisting of one or more morphemes and which typically occurs in the structure of phrases” (p.59). They also make a distinction between lexical and grammatical words. Lexical words are nouns, verbs, adjectives, pronouns, and adverbs. Such elements as prepositions, articles, conjunctions, and forms indicating number and tense are grammatical words (p.59). Irina Arnold believes all the definitions of the word are “dependent upon the line of approach, the aim the scholar has in view” (p.30). She states that for a comprehensive word theory, a description seems more appropriate than a definition:

The word is the fundamental unit of language. It is a dialectical unity of form and content. Its content or meaning is not identical to notion, but it may reflect human notions, and in this sense may be considered as the form of their existence. Concepts fixed in the meaning of words are formed as generalized and approximately correct reflections of reality; therefore, in signifying them, words reflect reality in their content. The acoustic aspect of the word serves to name objects of reality, not to reflect them. In this sense the word may be regarded as a sign. This sign, however, is not arbitrary but motivated by the whole process of its development. That is to say, when a word first comes into existence it is built out of the elements already available in the language and according to the existing patterns. (1986, p.31)

Although we may agree with some points of Arnold’s description of a word and believe that a word has many facets, we adhere to the simple definition of the word as the smallest free form found in a language. According to Bloomfield, ‘a minimum free form’ is a word. By this, he means that “the word is the smallest meaningful linguistic unit that can be used on its own” (as cited in Katamba, 2012, p. 6). We can contrast two words devil and devilish. The word devil is a minimum free form, and we cannot divide this word into pieces without destroying its meaning. The word devilish can be divided into pieces: devil and –ish. While devil has a meaning, -ish does not have any meaning, and it cannot stand on its own; therefore, devil is a word, but –ish is not a word.

William O’Grady, Michael Dobrovolsky, and Mark Aronoff also define a word a “minimal free form” (1993, p.112). A free form is an element which does not have to occur in a fixed position with respect to neighboring elements in a language.

1. A cat is a domestic animal.

2. I see a cat.

3. Many commercial cat foods are laced with corn.

In the first example, the word cat appears before the verb; in the second example, it appears after the verb, and in the third example, it appears in front of the noun. The reference to minimal is important because we do not identify phrases like the birds as one word, since it consists of two free forms—the and birds.

Even though we define words as minimal free forms, they are not minimal meaningful units of language because they can be broken down further. The word unemployment can stand alone, but it can also be broken into three parts: un-, employ, and -ment. The term for these minimal meaningful units is sign (de Saussure, 1959, p.68). A more common term in linguistics is a morpheme. Ferdinand de Saussure states that a sign is a combination of a concept and a sound image. Most linguists believe a sign has an arbitrary nature; however, it does not mean that any person can create a sign; he or she does not have a power to change the sign when it is established in the linguistic community (pp.68-69). William O’Grady, Michael Dobrovolsky, and Mark Aronoff also believe that most linguistic signs are arbitrary, which means that the connection between the sound of a given sign and its meaning is purely conventional, not rooted in some property of the object for which a sign stands (p.133). There is nothing about the sound-image (signifier [de Saussure, p.67]) of the concept (signified [de Saussure, p.67]) of frog, which refers to these creatures; therefore, we consider this sign to be chosen arbitrarily. The same word frog has different sounds in different languages: lyagushka (Russian), baka (Tatar), Frosch (German), kicker (Dutch), and grenouille (French). Some linguists may argue that onomatopoeia (the naming of a thing or action by a vocal imitation of the sound associated with it, as buzz, hiss, etc.) might be used to prove that the choice of the signifier is not always arbitrary, but de Saussure argues that “onomatopoeic formations are never organic elements of a linguistic system” (p.69). Moreover, although onomatopoeia is used to create a word, it does not have the same signifier in all the languages: buzz (English), vızıltı (Turkish), hudziennie (Belorussian), zhuzhzhanie (Russian), zumbido (Spanish), kêu vo vo (Vietnamese), etc. All these examples prove the arbitrary nature of a sign.

4.2 Morphological Structure of Words

Morphology is the study of structure, or form, or description of word-formation (as inflection, derivation, and compounding) in language and the system of word-forming elements and processes in a language (Webster, p.1170). William O’Grady, John Archibald, Mark Aronoff, and Janie Rees-Miller add that morphology is “the system of categories and rules involved in word-formation and interpretation” (2001, p.720). In morphology, the proper topic of study is the play of prefixes and suffixes or the internal changes within the word, which modify the word’s basic meaning. Modern descriptive linguists prefer such traditional terms as inflectional endings, root, stem, and morpheme. Where the traditional grammar would describe cats as consisting of the root cat and –s as an inflectional plural ending, the modern structural linguist would describe both cat and the ending–s as two different morphemes or units of meaning --one carrying the basic meaning of the word; the other, the accessory notion of plurality. However, a distinction would be set up between the two by labeling cat as a free morpheme, which could be used in isolation, and ending–s as a bound morpheme, which has no separate existence. Bloomfield labeled the meaning of the morpheme a “sememe” (as cited in Chisholm, 1981, p. 16); however, linguists did not study the meaning of a morpheme, so this term was dropped out of usage in linguistics. Bloomfield recognized that the complex meaning in a language is not simply the result of combining morphemes. He called the basic feature of arrangement of morphemes a taxeme(1935, p.116). He believes taxemes are meaningless, if taken in the abstract. Combinations of single taxemes occur as conventional grammatical arrangements, tactic forms (p.116). In a linguistic system, a taxeme is parallel to the phoneme in that neither has a meaning, but each is a minimal form-- a phoneme at the phonological level and a taxeme at the grammatical level.

4.2.1 Free and Bound Morphemes

A morpheme, which can occur alone as an individual word, is called a free morpheme, whereas a morpheme which can occur only with another morpheme is called a bound morpheme. The morpheme think is a free morpheme; however, morphemes un- and –able in the word unthinkable are bound morphemes. As we mentioned before, any concrete realization of a morpheme is called a morph. A morph should not be confused with a syllable. The difference between them is that “while morphs are manifestations of morphemes and represent specific meaning, syllables are parts of words which are isolated only on the basis of pronunciation” (Jackson & Zé Amvela, 2007, p.4). Other examples of a morpheme’s change when it is combined with another element can be traced in the following examples: the final segment of permit is [t] when it stands alone; however, when the word combines with the morpheme –ion, [t] changes to [∫] in the word permission. Similar alternations are found in the words allude/allusion, alternate/alternation, amalgamate/amalgamation, annotate/annotation, and assuage/assuasive.

Victoria A. Fromkin et al. (2000) name morphemes that represent categories of words as lexical morphemes. They refer to items (book, pen, table, etc.), actions (go, run, swim, etc.), attributes (red, fair, long, short, etc.), and concepts (theory, notion, etc.) that can be described with words or illustrated with pictures. Such morphemes as –ly, un-, -ed, -s, a, the, an, about, to, this, that, etc. are considered grammatical morphemes; the speaker uses them to signal the relationship between a word and the context in which they are used. Prepositions and determiners belong to grammatical morphemes because they express only a limited range of concepts. It should be noted that not all lexical morphemes are free morphemes, and not all grammatical morphemes are bound morphemes. Such grammatical morphemes as prepositions (about, for, to, etc.) and determiners (this, that, a, an, the, etc.) are free morphemes because they can stand alone.

4.2.2 Roots and Affixes

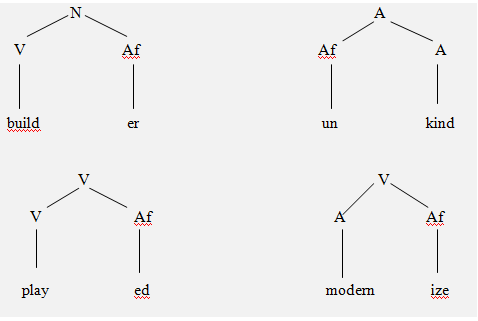

Complex words such as annotation, builder, professor, and others have internal structure. It is necessary not only to identify each component of the morphemes but also to classify them according to their contribution to the meaning and function of complex words. Typically, complex words consist of a root and one or more affixes. The root constitutes the core of the word and carries the major component of its meaning. Roots belong to a lexical category such as noun (N), verb (V), adjective (Adj), adverb (Adv), and preposition (P). Unlike roots, affixes are bound morphemes, and they do not belong to a lexical category. Affixes are subdivided into prefixes and suffixes. For example, when the suffix –er combines with the root build, the noun builder is coined to denote ‘one who builds.’ The internal structure of this word can be shown in a diagram, which O’Grady, Archibald, Aronoff, and Rees-Miller call “a tree structure” (p. 135). When an affix is attached to the root, the form is called a base or a stem (The terms base and stem may be used interchangeably). Sometimes a basecorresponds to the word’s root; for example, in cat, the root is cat, and it is also a base.

4.2.3 Stems

A stem is the actual form to which an affix (a suffix or a prefix) is added. In blacken, for example, the affix -en is added to the root black. Sometimes, an affix can be added to the form, which is larger than a root, e.g., authorization (n).

4.2.4 Types of affixes

We can distinguish three types of affixes in terms of their position relative to the stem. An affix, which is attached to the front of the stem, is called a prefix, and an affix, which is attached to the end of the stem, is called a suffix.

Some English prefixes and suffixes

| Prefixes | Suffixes |

| de+base de+cease dis+prove im+part im+bibe in+tone inter+fere in+trepid pre+fix pre+judge pre+side | employ+ment enjoy+ment frang+ible frenz+y fulmin+ate gorge+ous grate+ful hunt+er nation+al+ize profess+or prob+ation |

A less common type of affix is an infix, which occurs within another morpheme. Although it is common in some languages, in English it appears with expletives, which provide extra emphasis to the word. One might point to certain usages on the American frontier such as guaran-damn-tee , abso-bloody-lutely, and others.

4.2.5 Derivational and Functional Affixes

Functional affixes serve to convey grammatical meaning. They build different forms of one and the same word. Instead of creating a new word, functional affixes modify the form of the word in order to mark the grammatical subclass to which it belongs. A word form is defined as one of the different aspects a word may take as a result of inflection. Complete sets of all the various forms of a word when considered as inflectional patterns, such as plurality, declension and conjugation, are termed paradigms. A paradigm is defined as the system of grammatical forms characteristic of a word, e.g., work, work+s, work+ing, and work+ed.

Plurality inflection

| Singular | Plural |

| computer judge country dress fox buzz fly | computer+s judge+s countr+ies dresses foxes buzzes flies |

Tense Inflection

| Present | Past |

| play rule cry fix kiss dress | played ruled cried fixed kissed dressed |

Inflection of Derived or Compound Words

| Derived Form | Compound Form |

| kingdom+s professor+s achievement+s hospitalize+d activate+d clean+ed | baseball+s blackboard+s brother+s-in-law passer+sby babysit+s manhandle+d |

The difference between functional and derivational affixes is the following: derivational affixes serve to supply the stem with components of lexical and lexico-grammatical meaning, and thus form different words, whereas a functional affix does not change either the grammatical category or the type of meaning found in the word to which it belongs.

The word to which the suffix –s is attached is still a noun and still has the same type of meaning. Similarly, the past tense suffix –ed, attached to the verb, does not change the grammatical category: played is still a verb, and it still retains its meaning; played still denotes an action, regardless of the tense of the verb.

In contrast, derivational affixes change the category and the meaning of the form. Derivational affixes serve to supply the stem with components of lexical and lexico-grammatical meaning, thus forming different words (derivational affixes will be discussed more in depth in the word-formation section). Consider the following examples:

4.2.6 Cliticization

Some morphemes act like words in terms of their meaning or function; however, they are unable to stand alone by themselves. These morphemes are called clitics (O’Grady, Archibald, Aronoff, & Rees-Miller, 2001, p.139). These elements should be attached to another word, which is called a host word. A good example in English is the contracted forms, e.g., I’m, he’s, we’ve, they’re, and others. Clitics which are attached to the end of the host are called enclitics, as the examples show. Clitics which are attached to the beginning of the host are called proclitics; they are not observed in the English language but are characteristic of French: Suzanne les voit (Suzanne them- sees). Clitics act like affixes because they cannot stand alone; however, they are members of a lexical category such as verbs, pronouns, or nouns.

4.2.7 Internal Change/Alternation

Internal change is the process which substitutes one non-morphemic part for another to mark a grammatical cont

Date: 2015-12-18; view: 4409

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Part II: The Structure of the English Lexicon | | | Part V: Word-Formation 1 page |