CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Part V: Word-Formation 2 page

· Aphaeresis: the loss of one or more letters at the beginning of a word: story (history), cello (violoncello), phone (telephone).

· Syncope: the loss of one or more letters in the interior of a word: specs (spectacles), aphesis (aphaeresis).

· Apocope: the loss of one or more letters at the end of a word: ad (advertisement), ed (editor), fab (fabulous), prof (professor), and gym (gymnastics or gymnasium).

In some cases, speakers do not even realize that a particular word is the product of clipping; for example, the word zoo was formed from zoological garden.

5.10 Acronyms and Abbreviations

Acronyms are formed by taking the initial letters of some or all the words in a phrase or title and pronouncing them as a word. This type of word-formation is prevalent in names of organizations, military, and scientific terminology. Common examples are American Psychological Association (APA), Modern Language Association (MLA), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), Antisocial Behavior Order (ASBO), frequently asked questions (FAQ), Scholastic Achievement (or Aptitude) Test(s) (SAT), Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG), Designer Shoe Warehouse (DSW), Personal Identification Number (PIN), Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), random access memory (RAM), very important person (VIP), read only memory (ROM), and others.

In numerous cases, speakers do not realize that they are using an acronym. One example is radar (radio detecting and ranging), which is an acronym common throughout many languages. Other examples of acronyms are scuba (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus), and laser (light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation). It is widely assumed that the use of text shorthand known as acronyms was started as a result of the use of Morse Code to send and receive messages in the 19th century. Because telegraph companies charged the sender by the word, acronyms were invented to save the sender costs and to quicken the time and effort of the sending agent. Telegraph companies would not only charge by the word but would charge additional fees for numerals and words that could not be easily pronounced. So, acronyms which had no vowels were given vowels so as to make them pronounceable. A good example of this is the apparatus used for Radio Ranging and Detection. To send this collection of words, a sender would be charged for four separate words. Sending RRD would be only one word but charged an extra fee because it was not pronounceable. Sending radar gets the sender charged for only one pronounceable word. Modern society uses acronyms for many of the same reasons as the telegraph companies, e.g. ease of typing and speed of communication, be it on the modern day computer keyboard or the ubiquitous cell phone. Technically, there is a difference between acronyms and abbreviations. This difference becomes vague in many instances and makes it sometimes difficult to assign either word to the usage. While N.A.T.O. would be an abbreviation, it is also an acronym as in NATO. Some scholars distinguish between acronyms and initialisms; however, we do not recognize a sharp distinction between acronyms and initialisms, preferring the former as an inclusive label.

Abbreviation is a reduced version of a word, phrase, or sentence. Abbreviations are societal slangs. They come and go in waves. The reason for abbreviations is linguistic economy. Communicators value succinct language, and abbreviations contribute to concise style. Technological constraints contribute to the use of abbreviations. They also help to convey “a sense of social identity; to use an abbreviated form is to be ‘in the know’—a part of the social group to which the abbreviation belongs” (Crystal, 2005, p.120). Those who are computer savvy will be recognized by their extensive use of abbreviations such as WYSIWYG (What you see is what you get), and other similar abbreviations.

Now abbreviations are part netspeak and textspeak, which is a rapidly emerging jargon used among Internet users. David Crystal has compiled a glossary of netspeak and textspeak, and some examples illustrated here are borrowed from the Glossary: bps (bits per second), four-oh-four [404] (a term identifying an error message shown on screen when a browser makes a faulty request to a server), and others (Crystal, 2004). There are a lot of abbreviations used by “species of spoken shorthand” (Crystal, 2004, p.120): OK (all correct), PDQ (pretty damn quick), GTT (gone to Texas), BTW (by the way), ETA (estimated time of arrival), FYI (for your information), POS (parent over shoulder), ROFL (rolling on the floor laughing), RSVP (Répondez s'il vous plait), BRB (Be right back), TTYL (Talk to you later), and others.

Part VI: Semantics

The term semantics (sémantique) was created by Michel Bréal in 1883 to refer to the science of the study of meaning (as cited in Leroy, 1967, p. 19). Some scholars use the terms semasiology and semantics interchangeably. Keith Allan defines semantics as “the study of meaning in human languages, the study and representation of the meaning of every kind of constituent and expression in a language (morph, word, phrase, clause, sentence, and text) and also their meaning relations” (Allan, 2009). Semasiology is “the science of meanings or sense development (of words); the explanation of the development and changes of the meanings of words” (Encyclopedia). This term was first introduced by Christian Karl Reisig in 1825. The name comes from the Greek sēmasiā ‘signification’ (from sēma ‘sign’ sēmantikos ‘significant’ and logos ‘learning’). Scholars do not argue about the differences between semasiology and semantics. They believe they are synonymous when applied to philology (Ullman, 1951, p.5), but semantics has an additional area of application—it is used as a generic term for the study of relations between signs and things signified (Read, 1948, p.78).

As we said earlier, some scholars treat semaseology and semantics as synonyms; however, scholars differentiate between semasiology and onomasiology. As the Swiss Romanist Kurt Baldinger notes, “Semasiology…considers the isolated word and the way its meanings are manifested, while onomasiology looks at the designation of a particular concept, that is, at a multiplicity of expressions which form a whole” (1980, p. 278). Baldinger further explains that the difference between semasiology and onomasiology is meaning and naming: semasiology takes its starting point in a word as a form and charts the meanings that the word can occur with; onomasiology takes its starting point in a concept and investigates different expressions by which the concept is designated, or named (p.278). To put it simply, a semasiologist asks, “What is the meaning of the word inhabit?” An onomasiologist asks, “How to name the concept to occupy as a place of settled residence?” We will consider semasiology and semantics synonymic terms, and in our book, we will use semantics more often than semasiology so that not to confuse the readers.

W. N. Fransis (1958) believes that semantics studies four different kinds of meanings. One of them is notional meaning when a word expresses ideas, concepts, images, and feelings. It can also be defined as an object, relationship, or class of objects or relationships in the outside world that is referred to by a word. Fransis calls it referential meaning, and the object, relationship, and class of objects outside world to which a word refers is called its referent. Also the meaning of a word is considered as the sum total of what it contributes to all the utterances in which it appears, which Francis calls distributional meaning (1958, p.31).

John Lyons’s definition is pretty simple. He defines semantics as the study of meaning (1977, p.1). Frank Palmer argues in his book, Semantics:

[S]emantics is not a single, well-integrated discipline. It is not a clearly - defined level of linguistics, not even comparable to phonology or grammar. Rather it is a set of studies of the use of language in relation to many different aspects of experience, to linguistic and non-linguistic context, to participants in discourse, to their knowledge and experience, to the conditions under which a particular bit of language is appropriate. (1981, p. 206)

Although the term meaning may seem familiar to us, it has several meanings itself. Dictionaries provide literal meanings of a word; however, when we communicate, we convey other meanings besides the ones registered in the dictionaries. By simply looking at common or even scholarly uses of the relevant terms, we will not make much progress in the study of meaning; therefore, we should look at it within the framework of academic or scientific study—within linguistics (Palmer, 1990, p. 5).

6.1 Types of Semantics

Stephen Ullman classifies semantics into lexical semantics, which concentrates on word-meanings (p.33), and syntactic semantics, which deals with “the meaning of parts of speech, parts of the sentence, and other grammatical categories” (p.34). He also identifies descriptive and historical semantics. Descriptive semantics is the science of meaning, and diachronic semantics is the science of changes of meaning (p.171).

Howard Jackson gives several types of semantics: pragmatic, sentence, lexical, philosophical, and linguistic. He states that pragmatic semantics studies the meaning of the utterances in the context; sentence semantics studies the meanings of the sentences and meaning relations between the sentences; lexical semantics is the study of meaning in relation to words, including both the meaning relations that words contract with each other and the meaning relations that words have with extra-linguistic reality; philosophical semantics is concerned with logical properties of language; and linguistic semantics deals with all aspects of meaning in natural languages, from meaning of utterances in context to the meanings of sounds in syllables (pp.246-247). Georgios Tserdanelis and Wai Yi Peggy Wong add compositional semantics as well, by which they understand “the way the meanings of the whole sentences are determined from the meanings of the words in them by the syntactic structure of the sentence” (2004, p.216). Lexical semantics deals with a lexicon or a group of words in a language. While lexical semantics deals with individual words, compositional semantics deals with the meanings of phrases and sentences.

6.2 Word-Meaning

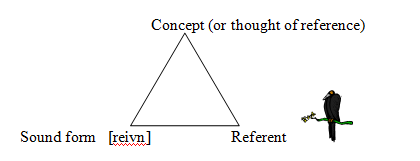

When people describe the world, they utter strings of sounds to convey the information to a listener. If they utter ‘Texas,’ they refer to a state, and if they utter ‘Chicago,’ they denote a city. The scholars who do not see any difference between the reference and the denotation apply a referential, or denotative, approach to the meaning of words. The entities they refer to, e.g., state and city, are named as referents, or denotata (singular denotatum). The commonly-known referential model of the meaning is Ogden/Richards basic triangle, which underlies the semantic systems of all the proponents of this school of thought.

As seen in this diagram, the sound-form of the linguistic sign [reivn] is connected with our concept of the raven which it denotes and through it with the referent, i.e. the actual bird. So, where is the place of meaning in this triangle? In the Course in General Linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure (1959) calls the combination of a concept and a sound-image a sign (Later, he renames concept as signified and sound-image as signifier). He made the arbitrariness of the linguistic sign one of the most basic principles of the theory: “The bond between the signifier and the signified is arbitrary” (1916, p. 67). Since the linguistic sign is arbitrary, the sound-form is arbitrary and cannot be the meaning of the word. This can be easily proven by comparing the sound-forms of different languages, which convey one and the same meaning, e.g., English [reivn], Russian [voron], Croatian [gavran], Dutch [raf], Polish [kruk], and Turkish [kuzgun]. Moreover, homophones may have identical sound-form but different meanings, e.g., [ai]-[ai] (I-eye) and [nait]-[nait] (night-knight). Most concepts are intrinsically the same for the whole mankind in one and the same period of its historical development; however, the sound-forms will always be different.

Some scholars who accept the referential approach to the meaning of words believe that the meaning of a linguistic sign is the concept underlying it; therefore, they substitute meaning for concept in the basic triangle. We argue that meaning is not concept; for example, the concept of cold may be expressed with words chilly, cool, frigid, frosty, gelid, and icy, but their meanings are slightly different, which proves that meaning and concept are not identical.

Others recognize meaning as the referent. They believe that unless they have scientifically accurate knowledge of the referent, they cannot give a scientifically accurate definition of the meaning of a word. Bloomfield argues, “In order to give scientifically accurate definition of meaning for every form of a language, we should have to have a scientifically accurate knowledge of everything in the speakers’ world” (1935, p.139). The actual extent of a person’s knowledge makes this impossible. We argue meaning and referent are not the same. “Meaning is linguistic, whereas the denoted object or the referent is beyond the scope of language” (Ginzburg, p. 15). One and the same object can be denoted by more than one word of a different meaning; for example, raven in different contexts may be denoted as bird, Corvus corax, and corvid. These analyses show that the meaning of a word cannot be identified with any of the points of the triangle: a sound form, or concept, or referent.

For some scholars, refer and denote are separate terms. They apply the representational approach to meaning. For them, denotation is used for the relationship between a linguistic expression and the world, while reference is used for the action of a speaker in choosing the items in the world. Lyons defines denotation as “a relation that applies in the first instance to lexemes and holds independently of particular occasions of utterance” (p.208). He believes reference is “the relationship between an expression and what that expression stands for on particular occasions of its utterance” (p.174). He states that reference depends on concrete utterances, not on abstract notions. It is a property of only expressions. It cannot relate single lexemes (book) to extra-linguistic objects since it is an utterance-dependent notion. Reference is not generally applicable to single word forms, and it is never applicable to single lexemes (p.197). For instance, the expressions Mary’s book, great books, and on the book may be used to establish a relationship of reference with specific items as referents. In these examples, the reference of these expressions containing book is partly determined by the denotation of the lexeme book in the overall system of the English language. So, the difference between denotation and reference is that “reference is an utterance-bound relation and does not hold of lexemes as such, but of expressions in the context” (Lyons, 1977, p.208). Semanticists who adopted the representational approach claim that the ability to talk about the world depends on the mental models of it. In this approach, meaning derives from language being a reflection of the conceptual structures.

Another approach to meaning, which is expressed mostly by structural linguists, is a functional approach. The proponents of a functional approach claim that the meaning of a linguistic unit may be studied only through its relation to other linguistic units and not through its relation to either concept or referent. Two examples illustrate this approach, e.g., improve and improvement. Their meanings are different because they function in speech differently. If we compare the context where they function, we notice that improve may be followed by a noun or a pronoun: improve him, improve the relationship, and improve it and may be preceded by a noun or a pronoun: he improves the relationship. Improvement may be followed by a prepositional phrase, e.g., improvement in studies, and it can also be preceded by an adjective, e.g., considerable improvement. We notice words improve and improvement occupy different positions in relation to other words. The position of a word in relation to other neighbouring words is called the distribution of a word. Since the distribution of the words, improve and improvement, is different, they belong to different classes; therefore, they have different meanings. The same approach may be applied to polysemous words whose meanings can be realized only in the context. The lexeme table has several meanings: a piece of furniture, a supply or source of food, a group of people assembled at or as if at a table (the bargaining table), a systematic arrangement of data, a condensed enumeration (a table of contents), and the upper flat surface of a gem. These meanings can be realized only in the context. People normally respond to the meanings in the context. If someone mentions a program about big cats in Africa, the listeners understand that the speaker is not talking about stray cats in Dallas. If someone uses the phraseological unit let the cat out of the bag, the listeners understand that the meaning should be derived from the whole phrase, not just from each constituent of it. The functionalists believe “semantic investigation is confined to the analysis of the difference or sameness of meaning, and the meaning is understood essentially as the function of the use of linguistic units” (Ginzburg, Khidekel, Knyazeva, & Sankin, 1979, p. 17).

6.3 Types of Meaning

Word-meaning is made up of various components, and their combination and the interrelation determine the inner facet of the word. These components represent types of meaning. The main types of meanings are grammatical, differential, distributional, and lexical meanings of words and word-forms.

6.3.1 Grammatical Meaning

Grammatical meaning may be defined as “the component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different words” (Ginzburg, Khidekel, Knyazeva, & Sankin, 1979, p. 18). The following words such as radios, babies, formulae, and studies have the grammatical meaning of plurality. The grammatical meaning of tense may be observed in verbs such as bought, traded, slept, delivered, and understood. The words newspaper’s (report), sons’ (letters), country’s (debt), and children’s (toys) share the grammatical meaning of case (possessive case).

6.3.2 Lexical Meaning

Lexical meaning has been defined by scholars in accordance with the main principles of different linguistic schools. Ferdinand de Saussure believes meaning is the relation between the object, or notion named, and the name itself. Leonard Bloomfield defines the meaning of a word as the situation in which the speaker utters it and the response it calls forth in the hearer (1935, p. 139). Arnold criticizes Bloomfield’s and Saussure’s approaches for incompleteness and proposes that “lexical meaning is the realisation of concept or emotion by means of a definite language system” (p. 38). This definition is broader because it takes into consideration not only uttered words but also human consciousness, which comprises not only mental activity but also emotions, volition, and pragmatic functions of language: communicative, emotive, evaluative, and aesthetic.

6.3.3 Denotative Meaning

The English lexicon is so vast and varied that clear categories of meaning are, at times, elusive. Words may have denotative and connotative meanings. Denotation is the “objective (dictionary) relationship between a lexeme and the reality to which it refers to” (Crystal, 2005, p. 170). The denotation of the lexeme spring corresponds to the season between winter and summer, regardless whether it is sunny, pleasant, or rainy. The denotation of the word cat corresponds to the set of felines. Further, we need to clarify the distinction between denotation and reference. Lyons defines the denotation of a lexeme as “the relationship that holds between that lexeme and persons, things, places, properties, processes and activities external to the language system” (1977, p.207). It is practically impossible to give the examples of denotation because denotation “holds independently of particular occasions of utterance” (p.208). If we say book, there is no particular reference to that book. It is something general. Reference is used to indicate the actual persons, things, places, properties, processes, and activities being referred to in a particular situation. By means of reference, a speaker or writer indicates which things, phenomena, and persons are being talked about. Reference depends on concrete utterances, not on abstract notions. It is a property only of expressions. It cannot relate single lexemes (book) to extra-linguistic objects since it is an utterance-dependent notion. Reference is not generally applicable to single word forms, and it is never applicable to single lexemes (p.197). As mentioned earlier, the expressions Mary’s book, great books, and on the book may be used to establish a relationship of reference with specific items as referents. In these examples, the reference of these expressions containing book is partly determined by the denotation of the lexeme book in the overall system of the English language. So, the difference between denotation and reference is that “reference is an utterance-bound relation and does not hold of lexemes as such, but of expressions in the context” (Lyons, 1977, p.208). Denotation, on the other hand, is “a relation that applies in the first instance to lexemes and holds independently of particular occasions of utterance” (p.208).

6.3.4 Connotative Meaning

Connotation refers to the personal aspect of lexical meaning, often emotional associations which a lexeme brings to mind” (Crystal, 2005, p. 170). Connotation creates a set of associations. These associations create the connotation of the lexeme, but they cannot be its meaning. Sometimes a lexeme is highly charged with connotations. We call such lexemes loaded, e.g., fascism, dogma, and others. Irina Arnold differentiates between connotation and denotation. She believes “The conceptual content of a word is expressed in its denotative meaning; however, connotative component is optional” (1986, p. 40). Some scholars, such as Stephen Ullmann (1962, p.74), find a binary distinction between connotation and denotation. The best explanation of the relationship between denotation and connotation is given by Leech (1981): “The connotations of a language expression are pragmatic effects that arise from encyclopaedic knowledge about its denotation and also from experiences, beliefs, and prejudices, about the contexts in which the expression is typically used” (as cited in Allan & Brown, 2009, p. 138). Connotations express points of view and personal attitudes; therefore, they may cause certain reaction, which will motivate semantic extension and creation of a new vocabulary.

As part of the connotative meaning, lexemes may contain an element of emotive evaluation. The words console, condole, solace, comfort, cheer up, and sympathize refer to the assuaging of unhappiness and grief, but the emotive charge of the words console, condole, solace are heavier than in comfort, cheer up, and sympathize. Condole and solace are formal, and condole sounds fusty and pompous, whereas condole may sound more precious. Console may suggest the attempt to make up for a loss offering something in its place. “The emotive charge is one of the objective semantic features proper to words as linguistic units and forms part of the connotative component of meaning” (Ginzburg, Khidekel, Knyazeva, & Sankin, 1979, p. 21).

Stylistic Reference

Words differ in their emotive charge and in their stylistic reference. There is a relation between stylistic reference and emotive charge of words, and they are interdependent. Stylistic reference is discussed in more detail in 3.1 (Synchronic Approach to the Structure of the English Vocabulary). Stylistically, words can be identified as literary, neutral, and colloquial layers. With the exception of the neutral layer, all other layers are emotively charged, i.e., they have some connotational meaning. If we compare the following words such as pain, ache, pang, stitch, throe, and twinge, they all mean some state of physical, emotional, or mental lack of well-being. Among them, pain is neutral, and it is not emotively charged. When we use the word ache, the connotation of ‘long-lasting’ is added to the meaning of pain. On the contrary, pang is pain but is sudden and sharp and is like to recur. A twinge is pretty much like a pang but milder in intensity. A throe is a violent and convulsive pain, and a stitch is a sudden, sharp, and piercing pain.

Also, these words except stitch have figurative application to mental and spiritual suffering: the pain of separation, the ache of loneliness, a pang of remorse, the throes of indecision, and a twinge of regret. “The emotive charge is one of the objective semantic features proper to words as linguistic units and forms part of the connotational component of meaning” (Ibid, p.21).

6.3.5 Differential Meaning

When the semantic component serves to distinguish one word from all others containing identical morphemes, then that semantic component contains differential meaning. Differential meaning can be illustrated in the following examples: in the compound words barman, boatman, cabman, and caveman, the components bar, boat, cab, and cave serve to distinguish these words from one another; therefore, they have differential meaning.

6.3 6 Distributional Meaning

Distributional meaning is the meaning ofthe order and arrangement of morphemes composing the word. Lyons (1968) states the idea that the attachments between elements within a word are firmer than are the attachments between words themselves (as cited in Saeed, p. 57). Some examples may illustrate this approach. The order of the morphemes is fixed in the following lexemes: reader, disappointment, and actually. The order of the morphemes cannot be changed without disturbance of its meaning. The following formations, er+read, or ment+appoint+dis do not make any sense, therefore proving the arrangement of morphemes is fixed, and these morphemes cannot be rearranged arbitrarily. Distributional meaning may be observed not only in lexemes but in collocations as well; for example, in collocations kick the bucket, in a stew of something and someone, and get one’s wires crossed, the arrangement of words is fixed, and any attempt to make changes in the structure will disturb the meaning. Summing up, distributional meaning is the meaning of the pattern of the arrangement of the morphemes composing the word and the arrangement of lexemes creating a collocation. Distributional meaning is found in all words composed of more than one morpheme (builder, not erbuild) and in trite metaphors: a flight of fancy, a heart of gold, and a shadow of a smile.

6.4 Phonetic, Morphological, and Semantic Motivation of Words

The term motivation denotes “the relationship existing between the phonemic or morphemic composition and structural pattern of the word, on the one hand, and its meaning on the other” (Arnold, p. 33). Three main types of motivation are observed: phonetical, morphological, and semantic.

Phonetical motivation occurs when there is a certain similarity between the sound-form of a word and its meaning when speech sounds may suggest spatial and visual dimensions, shape, and size, e.g., tick- tock, cuckoo, ratatat and sizzle. These lexemes are phonetically motivated because the sound clusters are a direct imitation of the sounds these words denote. This process in linguistics is onomatopoeia, which is “the use of a word for which the connection between sound and meaning seems non-arbitrary because the word’s sound echoes its meaning” (Denham & Lobeck, 2011, p. 140). Although the examples of onomatopoeia show that a certain non-arbitrary element of lexemes exists, these formations are never organic elements of a language system (de Saussure, 1959, p. 69). Moreover, these sound imitations are not the same in all languages; for example, English bow-bow corresponds to French ouaoua, which proves that even sound imitations in different languages are somewhat arbitrary. Other examples illustrate this assumption: cuckoo (English), kukučka (Slovak), kukushka (Russian), koekoek (Dutch), Kuckuck (German), dzeguze (Latvian), gegutė (Lithuanian), kukavica (Slovenian), guguk kuşu (Turkish), and kuke (Tatar). Interjections are closely related to onomatopoeia; however, they do not contradict the arbitrariness of the sound-form (e.g., English ouch! refers to French aïe!, to Russian oi!, to Ukranian oi!, and to Turkish uf!). Interjections are “spontaneous expressions of reality dictated, so to speak, by natural forces (de Saussure, 1959, p. 69). As seen from the argument above, phonetical motivation, a direct connection between the phonetic structure of the word and its meaning, is not universally recognized in modern linguistic science.

Date: 2015-12-18; view: 1248

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Part V: Word-Formation 1 page | | | Part V: Word-Formation 3 page |