CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Feature: Spotlight on Treating Inflammatory Acne

| T |

he therapeutic benefit of topical retinoids in reducing inflammatory acne lesions when used as monotherapy, or in combination with other topical agents, has not been fully appreciated by clinicians, including dermatologists. Though it?s widely accepted that the primary lesion in the pathogenesis of acne is the microcomedone, and we have long recognized that topical retinoids are clinically effective comedolytic agents, a disconnect still occurs. This happens when a clinician treats a patient with predominantly inflammatory acne and loses track of the concept that inflammatory acne lesions once began as microcomedones, and may only sometimes pass through a clinically evident closed comedonal phase.

|

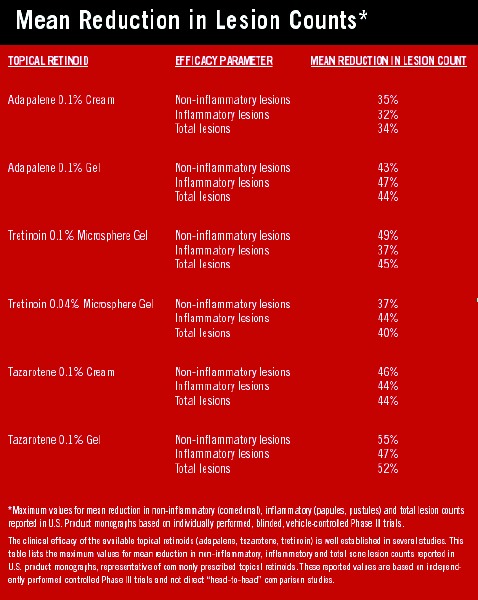

This article is based on the current literature assessing the impact of topical retinoid therapy for inflammatory acne, supporting the concept that topical retinoids are an important foundation for effective acne treatment, best initiated early in the course of therapy, regardless of whether the clinical presentation is predominantly comedonal or inflammatory. The ability to use topical retinoids as monotherapy or in combination with other topical agents, such as benzoyl peroxide and/or topical antibiotics, is well-established in multiple clinical studies and over years of clinical use.

Understanding Acne Pathogenesis and its Relationship to Topical Retinoid Use

The significance of the microcomedone as the primordial lesion of acne is widely appreciated by dermatologists. The microclimate created by abnormal keratinization and desquamation occurring within the follicular canal, combined with the increased sebum production associated with acne vulgaris, precedes the proliferation of commensal Propionibacterium acnes.

For several years it was believed, partially through scientific evidence, that comedonal and inflammatory acne lesions are caused by degradation of sebum by bacterial enzymes (lipases), producing free fatty acids that induce comedogenesis and trigger inflammation. This process is followed by thinning of the follicular epithelial lining, leading to loss of wall integrity. Duct wall disruption with subsequent spillage of follicular contents into the surrounding dermis leads to further augmentation of the inflammatory process. With improvements in technology supporting research, additional findings related to acne pathogenesis have helped to advance our understanding of currently available therapeutic agents, and provide a framework for discovery of novel treatments.

? Assessment of Microcomedone Formation. The formation of microcomedones precedes the development of visible comedonal and inflammatory acne lesions. Labeling techniques have correlated comedone formation and ductal hyperproliferation, establishing the presence of hyperproliferative keratins. Both the size and number of microcomedones increase in correlation with worsening of acne.

After initiation of topical retinoid therapy, the number of both comedones and microcomedones decreases; discontinuation of topical retinoid therapy results in relatively rapid reemergence of microcomedone formation.

? Cytokine Participation. The comedonal lesion as the focal point for formation of inflammatory acne is supported in part by evaluations of cytokine levels within lesions. Comedone formation has been demonstrated in vitro in the presence of interleukin (IL), specifically IL-1-alpha, and impaired by IL-1 antagonism. Analysis of cytokine content within histologically evaluated comedones demonstrated significant concentrations of IL-1-alpha within approximately 75% of comedones tested. Secretion of IL-1-alpha from comedones can induce innate ?nonspecific? (antigen independent) inflammation. Further amplification of the inflammatory cascade may be produced by lymphocytic infiltration directed against specific antigens, such as P. acnes. Further observation of increased hypersensitivity to P. acnes in patients with severe acne vulgaris.

? Role of Follicular Wall Integrity. Is based on the observations that:

? lymphocytic infiltration rather than neutrophilic infiltration is the initial histologic inflammatory event.

? disruption of the follicular duct wall.

Loss of integrity of the follicular duct wall was demonstrated in 14% of inflammatory lesions after 6 hours and 23% after 72 hours, confirming the presence of inflammation without follicular disruption. Neutrophils were noted within inflammatory infiltrate after approximately 2 days, within pustular lesions, and in greatest density when follicular wall rupture was observed.

Hormonal Influence. Androgen receptors have been identified within the pilosebaceous duct and sebaceous gland. The presence of 5-alpha reductase I within the pilosebaceous duct also supports a role for the interplay between circulating androgens, pilosebaceous unit function, and pathogenesis of acne lesions.

? Lipid Composition. Epidermal and sebaceous lipid composition may play a role in comedogenesis. Orderly desquamation requires a natural progression in corneocyte production with the formation of a lipid-encapsulated lattice-like network, and proper balance in lipid composition. Ceramide content is a significant component of normal stratum corneum. A phospholipid-enriched plasma membrane is converted to a ceramide-rich bi-layered membrane.

Skin surface lipids of normal patients (without acne) have been shown to contain markedly higher concentrations of skin surface linoleic acid than those found in acne patients, suggesting a relative ?fatty acid deficiency.? Increased sebaceous lipid content of linoleic acid has been correlated with decreased sebum production induced by treatment with oral isotretinoin and cyproterone acetate treatment.

? Role of Propionibacterium acnes. Suggests that P. acnes proliferation and involvement in acne lesion pathogenesis occurs after the development of microcomedonal and comedonal lesions. With the development of ductal hyperproliferation and sebum accumulation, a microclimate conducive to P. acnes proliferation is formed. As acne lesion formation progresses from normal follicles to comedonal lesions to inflammatory lesions, the prevalence of colonized follicles and the number of colony forming units (CFUs) of P. acnes increase.

Reduction in P. acnes concentration has been correlated with clinical improvement in patients treated with benzoyl peroxide and antibiotic therapy. The emergence of antibiotic-resistant P. acnes strains has also been associated with worsening of acne or lack of response to antibiotic therapy.

Recent evidence supports binding and stimulation of a specific ?pathogen recognition receptor,? called toll-like receptor-2 (TLR-2), by exoproducts produced by P. acnes. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are located on a variety of cell surfaces including mononuclear cells and dendritic cells involved in antigen recognition; TLR activation is involved in immune response through augmented stimulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine production. Therefore, it is possible to therapeutically reduce the impact of P. acnes on acne lesion development by reducing P. acnes organism concentration, or by interfering with the interaction between P. acnes exoproducts and TLR-2 receptors. Antibiotics and benzoyl peroxide exert an antimicrobial effect, reducing the number of P. acnes CFUs. Topical retinoids interfere with the interaction of P. acnes exoproducts and TLR-2, probably through reduction of TLR-2 surface membrane expression, and by interfering with formation of the ?follicular microclimate? conducive to P. acnes proliferation.

The optimal use of topical retinoids includes treatment with other agents, including topical antibiotics, benzoyl peroxide, and oral antibiotics. The combination of benzoyl peroxide application in the morning, including cleanser formulations, and topical retinoid therapy in the evening, maximizes response, especially due to the additive effect against inflammatory lesions; the topical retinoid provides for reduction in comedonal lesions.

As some patients may experience difficulty with local irritation related to combined benzoyl peroxide-topical retinoid use, topical retinoid therapy in combination with a topical antibiotic (clindamycin phosphate 1%) or an oral antibiotic have also been studied.

(COSE WINDOW)

Progressive Application Techniques

Fortunately, we have reached a time where the majority of acne patients can utilize topical retinoid therapy with little or no adverse consequence. There are some patients who are exquisitely ?retinoid sensitive? and quickly develop signs and symptoms of irritation; but they are the exception.

Another subset exhibits ?cumulative irritancy,? a presentation that can often be overcome by slower initiation of therapy, progressive application frequency, appropriate vehicle selection, and proper cleansing and moisturizer use. It must be appreciated that when combination topical therapies are used, other agents also carry with them their own irritancy potential. An approach that is often helpful in reducing irritation with topical acne treatment is to initiate nighttime application of topical retinoid therapy every other night for the first 1 week to 2 weeks, and then nightly thereafter. At this point, if there is no significant irritation, the recommended morning and/or daytime applications of other prescribed topical agents, such as benzoyl peroxide, topical antibiotic therapy, etc., can be added to the regimen.

This progressive ?go slow? approach allows a period of accommodation to the topical retinoid and other products, and facilitates identification of which component of the therapeutic protocol was the ?culprit? in initiating significant irritation, should it develop.

If a topical retinoid is being added to a topical acne regimen that?s already in progress and not associated with significant irritation, it should be started in the same progressive fashion at bedtime. Use of the established products that are being continued (ie, benzoyl peroxide, topical antibiotic, etc) should be applied earlier during the day.

Date: 2016-06-13; view: 669

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Feature: Overcoming the Challenges of Difficult Acne Cases | | | Feature: The Psychosocial Impact of Acne |