CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

DIGNITY

Fast-food workers and a newform of labor activism.

BY WILLIAM FINNEGAN

|

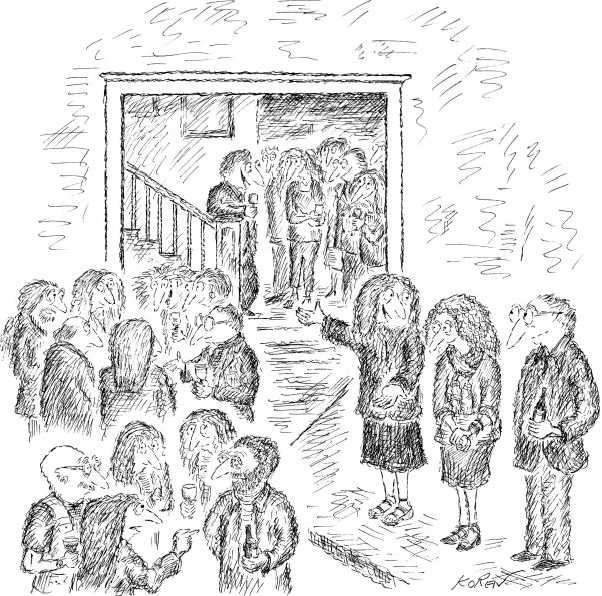

A demonstration by fast-food workers last week in Manhattan. One recent study found

that fifty-two per cent of fast-food workers require some form of public assistance.

PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK PETERSON / REDUX

| F |

or the customers, nothing has changed in the big, busy

McDonald's on Broadway at West 181st Street, in Washington

Heights. Promotions come and go—during the World Cup, the

French-fry package was suddenly not red but decorated with

soccer-related "street art," and, if you held your phone up to the box,

it would download an Augmented Reality app that let you kick

goals with the flick of a finger. New menu items appear—recently,

the Jalapeno Double and the Bacon Clubhouse, or, a while back,

the Fruit and Maple Oatmeal. But a McDonald's is a McDonald's.

This one is open twenty-four hours. It has its regulars, including a

panel of older gentlemen who convene at a row of tables near the

main door, generally wear guayaberas, and deliberate matters large

and small in Spanish. The restaurant doesn't suffer as much staff

turnover as you might think. Mostly the same employees, mostly

women, in black uniforms and gold-trimmed black visors, toil and

serve and banter with the customers year after year. The longtime

manager, Dominga de Jesus, bustles about, wearing a bright-pink

shirt and a worried look, barking at her workers, "La lineal La

lineal "

Behind the counter, though, a great deal has changed in the past

two years. Among the thirty-five or so non-salaried employees,

fourteen, at last count, have thrown in their lot with Fast Food

Forward, the New York branch of a growing campaign to unionize

fast-food workers. Underneath the lighted images of Big Macs and

Chicken McNuggets, back between the deep fryer and the meat

freezer, the clamshell grill and the egg station, the order screens

and the endless, hospital-like beeping of timers, there have been

sharp and difficult debates about the wisdom of demanding better

pay and forming a union.

Most of the workers here make minimum wage, which is eight

dollars an hour in New York City, and receive no benefits. Rosa

Rivera, a grandmother of four who has worked at McDonald's for

fourteen years, makes eight dollars and fifty cents. Exacerbating the

problem of low pay in an expensive city, nearly everyone is

effectively part time, getting fewer than forty hours of work a week.

And none of the employees seem to know, from week to week,

when, exactly, they will work. The crew-scheduling software used

by McDonald's is reputed to be sophisticated, but to the workers it

seems mindless and opaque. The coming week's schedule is posted

on Saturday evenings. Most of those who, like Rivera, have sided

with the union movement—going out on one-day wildcat strikes,

marching in midtown protests—suspect that they have been

penalized by managers with reductions in their hours. But just-in-

time scheduling is not easy to analyze.

Arisleyda Tapia, who has been working here for eight years, and

makes eight dollars and thirty-five cents an hour, says she was fired

last year by a supervisor for participating, on her own time, in a

protest. She was reinstated three days later by cooler management

heads, but Tapia, a single mother with a five-year-old daughter, says

that she now gets only thirty hours a week. She used to average

forty. "And they don't really post the schedule anymore," she told

me. "They just give you these."

She waved a thin strip of paper in the air. It was like the stuff that

comes out of a shredder. Tapia laughed, and mimicked a manager

frantically snipping each line out of a printed schedule, for

individual distribution. "This way, it's harder for us to see what's

going on at the store. You see only your own hours."

| T |

apia was a nurse in Santiago de los Caballeros, the second city

of the Dominican Republic. She had two children, Scarlet and

Steven. Her husband drove a taxi. Her mother, also a nurse, raised

orchids. When Tapia's marriage fell apart, she felt her hopes for her

children dimming. It was 2003; a banking crisis had cratered the

Dominican economy. With her mother's blessing, she left her job at

a big university hospital where she had worked for twelve years and

moved, alone, to New York. She rented a shared room in Inwood, a

working-class neighborhood in upper Manhattan, for fifty dollars a

week, got a job at a McDonald's in Inwood, and then a second job,

at the 181st Street McDonald's. She made minimum wage. Still,

she was able to send most of her paychecks home. "I made more in

a week here than I did in a month as a nurse there," she said. Her

children were provided for. College remained a possibility. Her

Facebook cover photo has a woman's closed eye with long lashes

and a big tear trickling down. "That's for missing my kids," she told

me.

Tapia struggled with depression. Her immigration status was work-

authorized, letting her obtain a Social Security number, and then it

wasn't. She got scammed by a lawyer. She feared she would be

deported. Tapia makes friends easily—if you walk the streets of

Inwood with her, you will see her merrily accosted by neighbors—

but she felt isolated. The sueno americano—the reason she still gives,

half-ruefully, for emigrating—had taken on nightmarish colors. She

felt trapped in a cold, foreign, overwhelming place. She felt that

people were following her. She went for therapy at public clinics.

Tapia, who is deeply religious, found herself looking for a sign from

God. One night, in church, she got it. Her anxiety receded. She

talks about the experience in awed, fierce tones.

She took up with a man—a taxi-driver—and on New Year's Day,

2009, she gave birth to a daughter, Ashley. The relationship with

the taxi-driver did not last. Tapia was thirty-seven. She found an

apartment on Sherman Avenue, in Inwood, across from the 207th

Street Subway Yard. The apartment was small and dark, partitioned

to create more rooms, and Tapia shared it with other renters. She

and Ashley slept in a single bed in a closet-size alcove. They still

sleep there. Tapia had already bought, sight unseen, a small rental

house in Santiago; her mother manages it, and the rent helps

support Scarlet and Steven.

cTake your pick—those people are talking schools. Next to

them is real estate, and over by the stairs is money."

With an infant, Tapia had to quit one of

her jobs. Money got tighter. She and

Ashley received food stamps—a hundred

and eighty-nine dollars a month—and,

crucially, an earned-income tax-credit

refund. But day care was expensive, and

Tapia could never get enough hours at work. Wary of the courts,

she received no child support. Still, her spirits were strong. Now she

lived for Ashley, who was bright and mischievous. Friends and co-

workers deluged the child with love and toys. Somebody gave her a

little plastic cash register. She banged away on it, piping, "Welcome

to McDonald's. How may I help you?"

One of Tapia's closest friends was Dominga de Jesus, her manager.

One of Tapia's closest friends was Dominga de Jesus, her manager.

La Dominga, as everybody calls her, is also Dominican. She lives in

the Bronx, started at the bottom herself at McDonald's, and has a

daughter slightly older than Ashley. The little girls are friends. La

Dominga was kind to Tapia in her despair. In turn, Tapia helped

Dominga when she had housing troubles. Between crises, the two

women loved to party together. Tapia was delighted for Dominga

when she went off to Hamburger University, the McDonald's

training center, in Oak Brook, Illinois, where she earned a degree

in Hamburgerology. The course there "sounded like a good party,"

Tapia told me, grinning.

In 2012, community organizers from New York Communities for

Change, a Brooklyn-based descendant of ACORN, started sniffing

around the McDonald's in Washington Heights. La Dominga—

perhaps forewarned, or simply aware of the long-standing vigilance

at McDonald's against any stirrings of union sentiment—spotted a

suspected organizer on one of her closed-circuit cameras. His name

was Alfredo Miase. He was Dominican. Tapia recalled, "She told

me, 'Don't talk to him.' "

But Tapia had recently had a run-in with another manager, who

kept her working, even though she had a fever, for hours. "Finally, I

couldn't take it," she told me. "I just couldn't stand up anymore, and

I went home. She suspended me for a week for that. She's gone

now, but she was abusive. That experience left me ready to do

something." So Tapia met with Miase, down the block, beyond the

closed-circuit cameras, skulking, scared. And she was not the only

one. "He was a very thoughtful, sympathetic guy," she said.

A small group of workers, nearly all women, started meeting with

Miase and another organizer, Marisol Vasquez, at a nearby

Chinese restaurant called Jimmy's. They discussed their problems

and what might be done. Tapia, unlike some American workers,

already had a solid grasp of what a union is. In the D.R., she had

been a member of the national nurses' union during a major dispute

with the ministry of health. That fight culminated in strikes that

caused a national furor. Doctors had also walked out. "Patients were

dying," she remembered. In the end, the government agreed to

meet with the strikers and address their demands.

The Service Employees International Union, the second-largest

union in the United States, was quietly funding the fast-food

campaign. The first public act was a one-day strike on November

29, 2012. Some two hundred workers, from around forty fast-food

outlets in New York City, gathered at dawn outside a McDonald's

on Madison Avenue in midtown, chanting, "Hey, hey, what do you

say, we demand fair pay." They had walked off jobs at Burger King,

Wendy's, Taco Bell, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Domino's Pizza, and

McDonald's. Their goals, they told reporters, were an industry-wide

raise to fifteen dollars an hour and the right to form a union

without retaliation. It was a day of rallies, walkouts, and a march

through Times Square. The Times called it "the biggest wave of job

actions in the history of America's fast-food industry." Tapia and

several co-workers from Washington Heights were in the thick of

it. La Dominga was shocked to see her friend's face in the crowd in

a photograph on her Facebook news feed.

| T |

he protests spread to the Midwest, with hundreds of fast-food

workers demonstrating in Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, and

Detroit. By the summer of 2013, workers in sixty cities across the

United States, even in the traditionally anti-union South, were

staging coordinated one-day walkouts and marches with a single

message: fifteen and a union. In December, it was more than a

hundred cities. The movement picked up political support.

President Obama renewed a long-neglected pledge to raise the

federal minimum wage, which is $7.25 an hour—it should be nine

dollars, he first suggested, and then lifted his sights, in early 2014,

to $10.10. That's a modest proposal; in 1968, the minimum wage, in

current dollars, was $10.95. Even so, minimum-wage legislation has

no chance of passing in this Congress. But opinion polls show wide

public support for a hike. Some cities and states have been bidding

up their own minimum-wage laws. In June, Seattle decided to raise

its minimum wage to fifteen dollars. Fast-food workers rightly took

credit for having made plausible a minimum wage that, less than

two years ago, sounded outlandish.

The fast-food giants have seemed clumsy, and wrong-footed by the

surge of protest. Their traditional defense of miserable pay—that

most of their employees are young, part time, just working for gas

money, really—has grown threadbare. Most of their employees

today are adults—median age twenty-eight. More than a quarter

have children. Particularly since the onset of the global recession of

2009, McJobs are often the only jobs available. And seventy per

cent of fast-food workers are indeed part time, working fewer than

forty hours a week.

McDonald's has tried to acknowledge the real lives of its workforce

by providing counselling through a Web site (since taken down)

and a help line called McResource. A sample personal budget was

offered online last year. The budget was full of odd assumptions:

that employees worked two full-time jobs, for instance, and that

health insurance could be bought for twenty dollars a month. The

gesture made the corporation look painfully out of touch. The same

thing happened with a health-advice page. Workers were advised to

break food into pieces to make it go farther, sing to relieve stress,

and take at least two vacations a year, since vacations are known to

"cut heart attack risk by 50%." Swimming, one learned, is great

exercise. Fresh fruit and vegetables are good for you, McDonald's

declared. A mother of two in Chicago, who had worked at

McDonald's for ten years, called the help line and found herself

counselled to apply for food stamps and Medicaid. This was, at

least, realistic. A recent study by researchers at the University of

California-Berkeley and the University of Illinois at Urbana-

Champaign found that fifty-two per cent of fast-food workers are

on some form of public assistance.

"Look, I know you think you've got the stuff, but I'm

telling you: walk God."

Sensitive to the beating that their brands

Sensitive to the beating that their brands

are taking in the escalating confrontation

with employees, the fast-food giants have

been leaving the hardball response to their lobby, the National

Restaurant Association. "The other N.R.A.," as it is known, is an

enormous organization, with nearly half a million member

businesses, but its strategic thinking seems to be dominated by the

major chains. It has fought minimum-wage legislation, at every

level of government, for decades. It has fought paid-sick-leave laws,

the Affordable Care Act, worker-safety regulations, restrictions on

the marketing of junk food to children, menu-labelling

requirements, and a variety of public-health measures, such as limits

on sugar, sodium, and trans fats. Its press releases now deride the

demands of fast-food workers as "nothing more than big labor's

attempt to push their own agenda." But internal N.R.A. documents,

leaked this spring to Salon, show the group's concern about the

"reputational attacks on our industry." They say that N.R.A. agents

are "closely monitoring social media for any plans or signs of

activity," and are even tracking the movements of one activist. Scott

DeFife, the chief N.R.A. spokesman, told me that the crowds at the

protests actually consist of organizers: "There's often not one

restaurant worker to be found among the crowds of organizers."

McDonald's has rarely hesitated to act aggressively on labor issues.

In 1990, it sued a tiny group called London Greenpeace for libel,

because of leaflets the group had distributed attacking the company.

According to Eric Schlosser's book "Fast Food Nation" (2001),

McDonald's had been successfully using Britain's plaintiff-friendly

libel laws to intimidate British mass media for many years. Two

members of London Greenpeace fought back. Although they could

not afford a lawyer, the court proceedings went on for more than a

decade, revealing, among other things, the extensive use by

McDonald's of spies—some meetings of London Greenpeace

apparently had as many spies in attendance as real members. The

"McLibel trial" was, from start to finish, a public-relations fiasco.

For the second-largest private employer in the world (after

Walmart), with more than thirty-five thousand restaurants in a

hundred and nineteen countries, McDonald's can be, in the court of

public opinion, remarkably inept.

In recent months, Fast Food Forward and its many partners—Fight

for 15 (Chicago), Stand Up KC (Kansas City), STL Can't Survive

on $7.35 (St. Louis)—have been rhetorically thrashing their

corporate opponents. The Berkeley-University of Illinois study,

commissioned by Fast Food Forward, found that American fast-

food workers receive almost seven billion dollars a year in public

assistance. That's a direct taxpayer subsidy, the activists argue, for

the fast-food industry. Taxpayers are also, by that logic, grossly

overpaying the industry's top management. According to the

progressive think tank Demos, fast-food executives' compensation

packages quadrupled, in constant dollars, between 2000 and 2013.

They now take home, on average, nearly twenty-four million

dollars a year. Their front-line workers' wages have barely risen in

that time, and remain among the worst in U.S. industry. The

differential between C.E.O. and worker pay in fast food is higher

than in any other domestic economic sector—twelve hundred to

one. In construction, by comparison, the differential is ninety-three

to one.

The fast-food chains insist that if they were to pay their employees

more they would have to raise menu prices. Their wages are

"competitive." But in Denmark McDonald's workers over the age

of eighteen earn more than twenty dollars an hour—they are also

unionized—and the price of a Big Mac is only thirty-five cents

more than it is in the United States. There are regional American

fast-food chains that take the high road with their employees. The

starting wage at In-N-Out Burger, which is based in Southern

California, and has two hundred and ninety-five restaurants in

California and the Southwest, is eleven dollars. Full-time workers

receive a complete benefits package, including life insurance—and

the burgers are cheap and good.

McDonald's, throughout its history, has denied responsibility for

the labor practices of its franchisees, who own and operate nearly

ninety per cent of its more than fourteen thousand outlets in the

United States. In March, seven class-action lawsuits were filed

against the company in three states—California, Michigan, and

New York—alleging wage theft and other violations of labor law.

In late July, the general counsel of the National Labor Relations

Board ruled, in connection with another set of complaints, that

McDonald's is a "joint employer" with its franchisees. The

corporation exercises, through its standard contract, the most

elaborate possible control over virtually every aspect of its

franchisees' operations, and the pay and the treatment of workers

are very largely determined by that control. Indeed, the lawsuits

allege that the crew-scheduling software that McDonald's

franchisees are required to use leads directly to the cost-cutting

practices that amount to wage theft.

McDonald's will fight the ruling and its implementation, both on

its own behalf and on behalf of other major franchisors. The

implications of the ruling, if it is upheld, are profound. Not only will

the responsibility of corporations for millions of workers be

increased sharply but the prospects for fast-food unionization will

brighten. Shop-by-shop organizing in what the economist David

Weil calls "the fissured workplace" is a Sisyphean chore. Having the

legally chosen representatives of the industry's workforce sit down

with the leaders of McDonald's, Burger King, and Wendy's, all of

whom are capable of a cost-benefit analysis of their business model,

makes more sense.

| I |

asked Arisleyda Tapia who she thought could raise her pay.

"Bruce," she said immediately. "He's rich."

She meant Bruce Colley, the owner of the McDonald's where she

works. Colley owns twenty-nine McDonald's franchises, including

nineteen in Manhattan. He grew up in Westchester County, and

graduated from the Trinity Pawling School and Cornell. When he

joined the family business, in 1980, his father, Dean, owned more

than a hundred McDonald's franchises in the Northeast. Dean was

master of foxhounds of the Golden's Bridge (New York) Hounds.

Bruce is a polo player. His net worth is not a matter of public

record. Still, you can see where Tapia got her impression.

Colley found himself in the news when, in 2003, he was reported to

be having an affair with Kerry Kennedy Cuomo, triggering her

divorce from Andrew Cuomo. According to the Post, Kerry was

"crushed" when Bruce decided not to leave his then wife for her.

Otherwise, Colley does a good job of staying out of the papers. (He

declined to comment for this article.) In July, 2013, during a heat

wave, Sheliz Mendez, one of Colley's employees at the McDonald's

in Washington Heights, fainted in the kitchen and had to be

hospitalized. Some of her co-workers walked off the job, protesting

the lack of air-conditioning, and began chanting on the sidewalk

outside. Reporters showed up. So did Colley. CBS New York

described him as a "McDonald's spokesman." He apologized for the

inconvenience to customers and employees and said that two of the

store's three air-conditioning units were already repaired. His

workers said that they had been complaining about the heat for

months and that the units were turned on only because camera

crews had appeared. Jamne Izquierdo, who has worked at the

Washington Heights outlet for nine years, said she had never seen

the air-conditioning on before.

As my stunt double, you 11 be doing all of my press

conferences, court appearances, and family reunions."

A year later, on another hot July day, I

stopped in the store and found it stifling.

Managers were setting up big portable

Managers were setting up big portable

fans near the counter. Colley did not want

another labor incident. I was waiting for

Tapia to finish her shift. There was a new

freestanding sign, touting the Bacon Clubhouse with a cryptic

boast: "Artisan is how this club rolls." On the workers' uniform caps,

multicolored stitching declared "FAMOUS CRISPY FUN LOVEABLE."

Was William Burroughs writing ad copy from the next world?

Having clocked out, Tapia emerged, looking drained, and eating

Fruit and Maple Oatmeal from a paper cup.

We walked south on Broadway. A rainstorm had broken the heat.

We passed through the spooky, puddled maw of the George

Washington Bridge Bus Station, its concrete arms hulking

overhead like a Soviet brutalist ruin. Tapia had sent Ashley, her

five-year-old, to visit her grandmother in the Dominican Republic.

She couldn't afford to go. It had been eleven years. She Skyped

with her kids and her mother several times a day, but it was strange,

this free time that she suddenly had. There was a national

conference of the fast-food workers' movement coming up, in

Chicago. The union was sending a couple of buses from New York.

Maybe she could go. We found a Dominican restaurant down

Broadway.

Did she really believe that Bruce Colley could unilaterally raise the

pay of all his employees to fifteen dollars an hour?

Tapia looked down. "He used to give us just one shirt," she said,

finally. "We tried to give a petition to La Dominga about people

getting their hours reduced, but she wouldn't accept it. Then Bruce

came and had a meeting with us. He came because we have a

strong union committee. He didn't go to any of his other stores. He

listened to us. Then they gave us each a box with four uniforms.

That was a real strike victory." She sighed. "But we know who our

real opponent is. It's the corporation. McDonald's."

The space between franchisees and a parent company is nowhere

more opaque than at McDonald's, where the price of admission is

exceptionally high: applicants must show at least seven hundred

and fifty thousand dollars of unborrowed money even to be

considered for a franchise, and the investment costs go up from

there. Very few franchisees fail to observe the code of omerta that

governs their relationship with the corporation. One disgruntled

franchisee in California recently broke the silence, telling the

Washington Post that McDonald's executives had advised her to

"pay your employees less" if she wanted to take home more herself.

Two former McDonald's managers recently went public with

confessions of systematic wage theft, claiming that pressure from

both franchisees and the corporation forced them to alter time

sheets and compel employees to work off the clock.

Having a union will put a stop to this type of injustice, Tapia

believes. And she was not wrong, I thought, about the importance

of tangible victories, however small. Building confidence was

crucial, even in the fissured workplace—showing doubters that

standing up for yourself need not always bring down the wrath of

the bosses on your head and could actually achieve benefits. "Some

people are too scared to say anything," she said. "They're scared to

talk to you, for instance—the media." I could confirm that. "It's not

that everybody working there supports the union. But they all want

us to keep fighting. They're afraid to fight themselves, but they

know they'll benefit when we win."

Date: 2015-01-11; view: 1575

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| What Are the Differences Between Travel Agent and Tour Operator? | | | But would the boat parties be reinstated? |