CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

How Franklin Roosevelt Secretly Ended the Gold Standard

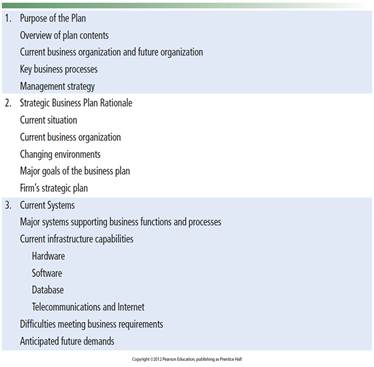

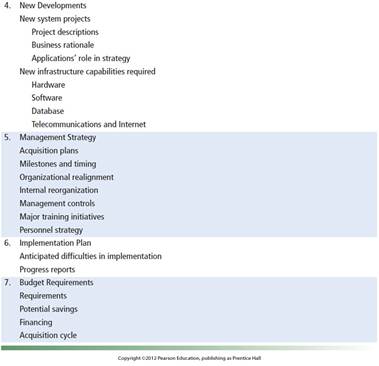

(Chapter 14: Contents including Table 14-1 in page 532-533 of textbook)

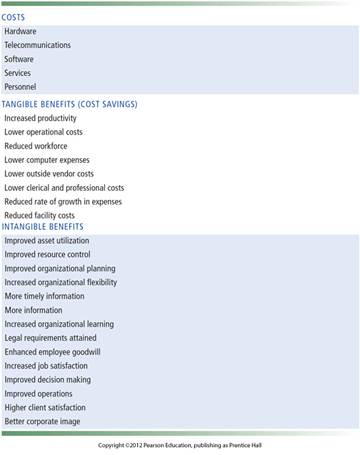

(Q-6) Mention the costs and benefits of information systems.

(Q-6) Mention the costs and benefits of information systems.

Table 14-3 lists some of the more common costs and benefits of systems.

Tangible benefits can be quantified and assigned a monetary value.

Intangible benefits, such as more efficient customer service or enhanced decision making, cannot be immediately quantified but may lead to quantifiable gains in the long run.

(Q-7) Analyze an international information systems architecture.

The major dimensions for developing an international information systems architecture are the global environment, the corporate global strategies, the structure of the organization, the management and business processes, and the technology platform.

(Q-8) Describe the three principles of reorganizing the business on an international scale (in terms of an international information systems support structure).

1. Organize value-adding activities along lines of comparative advantage. For instance, marketing/sales functions should be located where they can best be performed, for least cost and maximum impact; likewise with production, finance, human resources, and information systems.

2. Develop and operate systems units at each level of corporate activity— regional, national, and international. To serve local needs, there should be host country systems units of some magnitude.

3. Establish at world headquarters a single office responsible for development of international systems—a global chief information officer (CIO) position.

How Franklin Roosevelt Secretly Ended the Gold Standard

By Eric Rauchway Mar 21, 2013 4:28 PM GMT+0200

On March 4, 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt became president for the first time, promising an “adequate but sound” currency. The next day, a Sunday, he closed the nation’s banks. “We are now off the gold standard,” he privately declared to a group of advisers. Goldbugs in the president’s circle immediately began prophesying doom. One of his aides, Lewis Douglas, proclaimed “the end of Western civilization.”

How Roosevelt took this fateful step has been the subject of debate among historians, many of whom believe that the president flailed his way through his first weeks in office, and only gradually came to the decision to take the country off gold that April. But the evidence suggests that Roosevelt intended to do so from Day One for very specific reasons, although he delayed letting the rest of the country in on his plans.

Minutes after FDR had made his unsettling private disclosure, a secretary told him that reporters were clamoring to know if the U.S. had left the gold standard. “Tell them to ask a banker,” Roosevelt said. He clearly did not yet wish to say the truth publicly. First, he needed depositors to return the gold they had withdrawn in panic in the weeks preceding his inauguration.

Shame, Fear

By Tuesday, Americans had begun to bring gold in large quantities back to the banks. Perhaps they were shamed by the president’s identifying hoarding as the source of the panic, or maybe they feared prosecution under new penalties, including a tax on hoarding, then being discussed in Washington as ways of ensuring that gold came back to the Treasury. The Federal Reserve announced that it had the names of those who had taken out gold.

On Wednesday, Roosevelt convened his first press conference. More than 100 reporters crowded into a small office he had chosen to ensure intimacy, clustering at his desk. Then FDR said cheerfully, “As long as nobody asks me whether we are off the gold standard or gold basis, that is all right” -- which is to say, by professing he didn’t want to talk about the gold standard, Roosevelt artfully steered the conversation to the gold standard, and then discussed it at length, if obliquely.

First, FDR ran through various requirements for being on the gold standard. He made clear that paper money was no longer convertible into gold, nor was the metal available for export. But he declared that so far as buying gold back with other currency, “we are still on the gold standard.” When pressed as to whether these measures were a temporary expedient or permanent policy, Roosevelt said the U.S. would have a permanently “managed currency” and that “it may expand one week and it may contract another week. That part is all off the record.”

Thus did the reporters learn Roosevelt’s intentions. The U.S. was no longer on the gold standard, except so far as receiving gold was concerned, and he meant to adopt a permanent policy of managing the quantity of the currency. This way, he could bring commodity prices back up and maintain them at a level that would ensure producers a higher standard of living. But he didn’t want to announce the policy too abruptly, lest he induce panic.

War Chest

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve continued to take in gold. Guards, many of them former Marines armed with machine guns, oversaw the trucks bringing back the treasure, which would never again leave. “I am keeping my finger on gold,” Roosevelt said that Friday, and he did.

It would take the next nine months for Roosevelt’s program to take shape in law, but when it had, he controlled the value of the dollar, and had a war chest full of gold to defend it on international markets. He had the power to adjust the value of the currency in keeping with domestic economic needs, and he used it to drive commodity prices back up. In time, the new dollar -- managed to promote prosperity, a paper promise of gold stored, but always unavailable -- would become the basis for a world of such currencies defined by the Bretton Woods agreements.

Though some contemporary critics of Roosevelt never forgave him -- gold retained an alchemical power to turn nonsense into received wisdom -- others eventually endorsed his policy. The banker James Warburg initially complained that “sacred cows were being slaughtered,” but later reversed himself, as he said in an oral history he gave decades later. “I had to learn through being wrong that none of these things worked by the book,” he said. “A man can do idiotic things, but if the man in the street thinks the fellow is all right and going in the right direction, they don’t notice the idiotic things,” Warburg reflected. “So all you do is scare a bunch of orthodox economists and bankers, and they’re scared anyway, so it doesn’t make any difference.”

The recovery from the Great Depression began instantly with Roosevelt’s policy shift, in March 1933. He had changed expectations, and begun an administration that would use money as a tool to bring widespread prosperity -- rather than serve as a tool of moneyed interests.

(Eric Rauchway

is a professor of history at the University of California, Davis, and the author of the forthcoming “The Money-Makers: The Invention of Prosperity From Bullion to Bretton Woods” and “The Great Depression and the New Deal: A Very Short Introduction.” The opinions expressed are his own.)To contact the writer of this post: Eric Rauchway at earauchway@ucdavis.edu.

To contact the editor responsible for this post: Timothy Lavin at tlavin1@bloomberg.net.

Date: 2015-01-02; view: 3359

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Q-5) Describe an information systems plan. | | | FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT |