CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

WHY I WROTE CORALINE 6 page

Coraline stared at the leaves on the trees and at the patterns of light and shadow on the cracked bark of the trunk of the beech tree outside the window. Then she looked down at her lap, at the way that the rich sunlight brushed every hair on the cat’s head, turning each white whisker to gold.

Nothing, she thought, had ever been so interesting.

And, caught up in the interestingness of the world, Coraline barely noticed that she had wriggled down and curled catlike on her grandmother’s uncomfortable armchair, nor did she notice when she fell into a deep and dreamless sleep.

XII.

H ER MOTHER SHOOK HER gently awake.

“Coraline?” she said. “Darling, what a funny place to fall asleep. And really, this room is only for best. We looked all over the house for you.”

Coraline stretched and blinked. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I fell asleep.”

“I can see that,” said her mother. “And wherever did the cat come from? He was waiting by the front door when I came in. Shot out like a bullet as I opened it.”

“Probably had things to do,” said Coraline. Then she hugged her mother so tightly that her arms began to ache. Her mother hugged Coraline back.

“Dinner in fifteen minutes,” said her mother. “Don’t forget to wash your hands. And just look at those pajama bottoms. What did you do to your poor knee?”

“I tripped,” said Coraline. She went into the bathroom, and she washed her hands and cleaned her bloody knee. She put ointment on her cuts and scrapes.

She went into her bedroom—her real bedroom, her true bedroom. She pushed her hands into the pockets of her dressing gown, and she pulled out three marbles, a stone with a hole in it, the black key, and an empty snow globe.

She shook the snow globe and watched the glittery snow swirl through the water to fill the empty world. She put it down and watched the snow fall, covering the place where the little couple had once stood.

Coraline took a piece of string from her toy box, and she strung the black key on the string. Then she knotted the string and hung it around her neck.

“There,” she said. She put on some clothes and hid the key under her T-shirt. It was cold against her skin. The stone went into her pocket.

Coraline walked down the hallway to her father’s study. He had his back to her, but she knew, just on seeing him, that his eyes, when he turned around, would be her father’s kind gray eyes, and she crept over and kissed him on the back of his balding head.

“Hullo, Coraline,” he said. Then he looked around and smiled at her. “What was that for?”

“Nothing,” said Coraline. “I just miss you sometimes. That’s all.”

“Oh good,” he said. He put the computer to sleep, stood up, and then, for no reason at all, he picked Coraline up, which he had not done for such a long time, not since he had started pointing out to her she was much too old to be carried, and he carried her into the kitchen.

Dinner that night was pizza, and even though it was homemade by her father (so the crust was alternately thick and doughy and raw, or too thin and burnt), and even though he had put slices of green pepper on it, along with little meatballs and, of all things, pineapple chunks, Coraline ate the entire slice she had been given.

Well, she ate everything except for the pineapple chunks.

And soon enough it was bedtime.

Coraline kept the key around her neck, but she put the gray marbles beneath her pillow; and in bed that night, Coraline dreamed a dream.

She was at a picnic, under an old oak tree, in a green meadow. The sun was high in the sky and while there were distant, fluffy white clouds on the horizon, the sky above her head was a deep, untroubled blue.

There was a white linen cloth laid on the grass, with bowls piled high with food—she could see salads and sandwiches, nuts and fruit, jugs of lemonade and water and thick chocolate milk. Coraline sat on one side of the tablecloth while three other children took a side each. They were dressed in the oddest clothes.

The smallest of them, sitting on Coraline’s left, was a boy with red velvet knee britches and a frilly white shirt. His face was dirty, and he was piling his plate high with boiled new potatoes and with what looked like cold, whole, cooked, trout. “This is the finest of pic-nics, lady,” he said to her.

“Yes,” said Coraline. “I think it is. I wonder who organized it.”

“Why, I rather think you did, Miss,” said a tall girl, sitting opposite Coraline. She wore a brown, rather shapeless dress, and had a brown bonnet on her head which tied beneath her chin. “And we are more grateful for it and for all than ever words can say.” She was eating slices of bread and jam, deftly cutting the bread from a large golden-brown loaf with a huge knife, then spooning on the purple jam with a wooden spoon. She had jam all around her mouth.

“Aye. This is the finest food I have eaten in centuries,” said the girl on Coraline’s right. She was a very pale child, dressed in what seemed to be spider’s webs, with a circle of glittering silver set in her blonde hair. Coraline could have sworn that the girl had two wings—like dusty silver butterfly wings, not bird wings—coming out of her back. The girl’s plate was piled high with pretty flowers. She smiled at Coraline, as if it had been a very long time since she had smiled and she had almost, but not quite, forgotten how. Coraline found herself liking this girl immensely.

And then, in the way of dreams, the picnic was done and they were playing in the meadow, running and shouting and tossing a glittering ball from one to another. Coraline knew it was a dream then, because none of them ever got tired or winded or out of breath. She wasn’t even sweating. They just laughed and ran in a game that was partly tag, partly piggy-in-the-middle, and partly just a magnificent romp.

Three of them ran along the ground, while the pale girl fluttered a little over their heads, swooping down on butterfly wings to grab the ball and swing up again into the sky before she tossed the ball to one of the other children.

And then, without a word about it being spoken, the game was done, and the four of them went back to the picnic cloth, where the lunch dishes had been cleared away, and there were four bowls waiting for them, three of ice cream, one of honeysuckle flowers piled high.

They ate with relish.

“Thank you for coming to my party,” said Coraline. “If it is mine.”

“The pleasure is ours, Coraline Jones,” said the winged girl, nibbling another honeysuckle blossom. “If there were but something we could do for you, to thank you and to reward you.”

“Aye,” said the boy with the red velvet britches and the dirty face. He put out his hand and held Coraline’s hand with his own. It was warm now.

“It’s a very fine thing you did for us, Miss,” said the tall girl. She now had a smear of chocolate ice cream all around her lips.

“I’m just pleased it’s all over,” said Coraline.

Was it her imagination, or did a shadow cross the faces of the other children at the picnic?

The winged girl, the circlet in her hair glittering like a star, rested her fingers for a moment on the back of Coraline’s hand. “It is over and done with for us,” she said. “This is our staging post. From here, we three will set out for uncharted lands, and what comes after no one alive can say. . . .” She stopped talking.

“There’s a but, isn’t there?” said Coraline. “I can feel it. Like a rain cloud.”

The boy on her left tried to smile bravely, but his lower lip began to tremble and he bit it with his upper teeth and said nothing. The girl in the brown bonnet shifted uncomfortably and said, “Yes, Miss.”

“But I got you three back,” said Coraline. “I got Mum and Dad back. I shut the door. I locked it. What more was I meant to do?”

The boy squeezed Coraline’s hand with his. She found herself remembering when it had been she, trying to reassure him, when he was little more than a cold memory in the darkness.

“Well, can’t you give me a clue?” asked Coraline. “Isn’t there something you can tell me?”

“The beldam swore by her good right hand,” said the tall girl, “but she lied.”

“M-my governess,” said the boy, “used to say that nobody is ever given more to shoulder than he or she can bear.” He shrugged as he said this, as if he had not yet made his own mind up whether or not it was true.

“We wish you luck,” said the winged girl. “Good fortune and wisdom and courage—although you have already shown that you have all three of these blessings, and in abundance.”

“She hates you,” blurted out the boy. “She hasn’t lost anything for so long. Be wise. Be brave. Be tricky.”

“But it’s not fair,” said Coraline, in her dream, angrily. “It’s just not fair. It should be over.”

The boy with the dirty face stood up and hugged Coraline tightly. “Take comfort in this,” he whispered. “Th’art alive. Thou livest.”

And in her dream Coraline saw that the sun had set and the stars were twinkling in the darkening sky.

Coraline stood in the meadow, and she watched as the three children (two of them walking, one flying) went away from her across the grass, silver in the light of the huge moon.

The three of them came to a small wooden bridge over a stream. They stopped there and turned and waved, and Coraline waved back.

And what came after was darkness.

Coraline woke in the early hours of the morning, convinced she had heard something moving, but unsure what it was.

She waited.

Something made a rustling noise outside her bedroom door. She wondered if it was a rat. The door rattled. Coraline clambered out of bed.

“Go away,” said Coraline sharply. “Go away or you’ll be sorry.”

There was a pause, then the whatever it was scuttled away down the hall. There was something odd and irregular about its footsteps, if they were footsteps. Coraline found herself wondering if it was perhaps a rat with an extra leg. . . .

“It isn’t over, is it?” she said to herself.

Then she opened the bedroom door. The gray, predawn light showed her the whole of the corridor, completely deserted.

She went toward the front door, sparing a hasty glance back at the wardrobe-door mirror hanging on the wall at the other end of the hallway, seeing nothing but her own pale face staring back at her, looking sleepy and serious. Gentle, reassuring snores came from her parents’ room, but the door was closed. All the doors off the corridor were closed. Whatever the scuttling thing was, it had to be here somewhere.

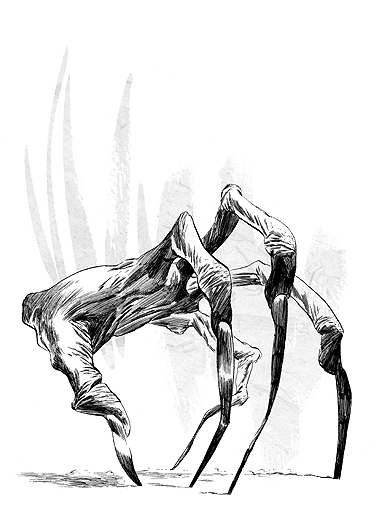

Coraline opened the front door and looked at the gray sky. She wondered how long it would be until the sun came up, wondered whether her dream had been a true thing while knowing in her heart that it had been. Something she had taken to be part of the shadows under the hall couch detached itself from beneath the couch and made a mad, scrabbling rush on its long white legs, heading for the front door.

Coraline’s mouth dropped open in horror and she stepped out of the way as the thing clicked and scuttled past her and out of the house, running crablike on its too-many tapping, clicking, scurrying feet.

She knew what it was, and she knew what it was after. She had seen it too many times in the last few days, reaching and clutching and snatching and popping blackbeetles obediently into the other mother’s mouth. Five-footed, crimson-nailed, the color of bone.

It was the other mother’s right hand.

It wanted the black key.

XIII.

C ORALINE’S PARENTS NEVER SEEMED to remember anything about their time in the snow globe. At least, they never said anything about it, and Coraline never mentioned it to them.

Sometimes she wondered whether they had ever noticed that they had lost two days in the real world, and came to the eventual conclusion that they had not. Then again, there are some people who keep track of every day and every hour, and there are people who don’t, and Coraline’s parents were solidly in the second camp.

Coraline had placed the marbles beneath her pillow before she went to sleep that first night home in her own room once more. She went back to bed after she saw the other mother’s hand, although there was not much time left for sleeping, and she rested her head back on that pillow.

Something scrunched gently as she did.

She sat up, and lifted the pillow. The fragments of the glass marbles that she saw looked like the remains of eggshells one finds beneath trees in springtime: like empty, broken robin’s eggs, or even more delicate—wren’s eggs, perhaps.

Whatever had been inside the glass spheres had gone. Coraline thought of the three children waving good-bye to her in the moonlight, waving before they crossed that silver stream.

She gathered up the eggshell-thin fragments with care and placed them in a small blue box which had once held a bracelet that her grandmother had given her when she was a little girl. The bracelet was long lost, but the box remained.

Miss Spink and Miss Forcible came back from visiting Miss Spink’s niece, and Coraline went down to their flat for tea. It was a Monday. On Wednesday Coraline would go back to school: a whole new school year would begin.

Miss Forcible insisted on reading Coraline’s tea leaves.

“Well, looks like everything’s mostly shipshape and Bristol fashion, luvvy,” said Miss Forcible.

“Sorry?” said Coraline.

“Everything is coming up roses,” said Miss Forcible. “Well, almost everything. I’m not sure what that is.” She pointed to a clump of tea leaves sticking to the side of the cup.

Miss Spink tutted and reached for the cup. “Honestly, Miriam. Give it over here. Let me see. . . .”

She blinked through her thick spectacles. “Oh dear. No, I have no idea what that signifies. It looks almost like a hand.”

Coraline looked. The clump of leaves did look a little like a hand, reaching for something.

Hamish the Scottie dog was hiding under Miss Forcible’s chair, and he wouldn’t come out.

“I think he was in some sort of fight,” said Miss Spink. “He has a deep gash in his side, poor dear. We’ll take him to the vet later this afternoon. I wish I knew what could have done it.”

Something, Coraline knew, would have to be done.

That final week of the holidays, the weather was magnificent, as if the summer itself were trying to make up for the miserable weather they had been having by giving them some bright and glorious days before it ended.

The crazy old man upstairs called down to Coraline when he saw her coming out of Miss Spink and Miss Forcible’s flat.

“Hey! Hi! You! Caroline!” he shouted over the railing.

“It’s Coraline,” she said. “How are the mice?”

“Something has frightened them,” said the old man, scratching his mustache. “I think maybe there is a weasel in the house. Something is about. I heard it in the night. In my country we would have put down a trap for it, maybe put down a little meat or hamburger, and when the creature comes to feast, then—bam!—it would be caught and never bother us more. The mice are so scared they will not even pick up their little musical instruments.”

“I don’t think it wants meat,” said Coraline. She put her hand up and touched the black key that hung about her neck. Then she went inside.

She bathed herself, and kept the key around her neck the whole time she was in the bath. She never took it off anymore.

Something scratched at her bedroom window after she went to bed. Coraline was almost asleep, but she slipped out of her bed and pulled open the curtains. A white hand with crimson fingernails leapt from the window ledge onto a drainpipe and was immediately out of sight. There were deep gouges in the glass on the other side of the window.

Coraline slept uneasily that night, waking from time to time to plot and plan and ponder, then falling back into sleep, never quite certain where her pondering ended and the dream began, one ear always open for the sound of something scratching at her windowpane or at her bedroom door.

In the morning Coraline said to her mother, “I’m going to have a picnic with my dolls today. Can I borrow a sheet—an old one, one you don’t need any longer—as a tablecloth?”

“I don’t think we have one of those,” said her mother. She opened the kitchen drawer that held the napkins and the tablecloths, and she prodded about in it. “Hold on. Will this do?”

It was a folded-up disposable paper tablecloth covered with red flowers, left over from some picnic they had been on several years before.

“That’s perfect,” said Coraline.

“I didn’t think you played with your dolls anymore,” said Mrs. Jones.

“I don’t,” admitted Coraline. “They’re protective color-ation.”

“Well, be back in time for lunch,” said her mother. “Have a good time.”

Coraline filled a cardboard box with dolls and with several plastic doll’s teacups. She filled a jug with water.

Then she went outside. She walked down to the road, just as if she were going to the shops. Before she reached the supermarket she cut across a fence into some wasteland and along an old drive, then crawled under a hedge. She had to go under the hedge in two journeys in order not to spill the water from the jug.

It was a long, roundabout looping journey, but at the end of it Coraline was satisfied that she had not been followed.

She came out behind the dilapidated old tennis court. She crossed over it, to the meadow where the long grass swayed. She found the planks on the edge of the meadow. They were astonishingly heavy—almost too heavy for a girl to lift, even using all her strength, but she managed. She didn’t have any choice. She pulled the planks out of the way, one by one, grunting and sweating with the effort, revealing a deep, round, brick-lined hole in the ground. It smelled of damp and the dark. The bricks were greenish, and slippery.

She spread out the tablecloth and laid it, carefully, over the top of the well. She put a plastic doll’s cup every foot or so, at the edge of the well, and she weighed each cup down with water from the jug.

She put a doll in the grass beside each cup, making it look as much like a doll’s tea party as she could. Then she retraced her steps, back under the hedge, along the dusty yellow drive, around the back of the shops, back to her house.

She reached up and took the key from around her neck. She dangled it from the string, as if the key were just something she liked to play with. Then she knocked on the door of Miss Spink and Miss Forcible’s flat.

Miss Spink opened the door.

“Hello dear,” she said.

“I don’t want to come in,” said Coraline. “I just wanted to find out how Hamish was doing.”

Miss Spink sighed. “The vet says that Hamish is a brave little soldier,” she said. “Luckily, the cut doesn’t seem to be infected. We cannot imagine what could have done it. The vet says some animal, he thinks, but has no idea what. Mister Bobo says he thinks it might have been a weasel.”

“Mister Bobo?”

“The man in the top flat. Mister Bobo. Fine old circus family, I believe. Romanian or Slovenian or Livonian, or one of those countries. Bless me, I can never remember them anymore.”

It had never occurred to Coraline that the crazy old man upstairs actually had a name, she realized. If she’d known his name was Mr. Bobo she would have said it every chance she got. How often do you get to say a name like “Mr. Bobo” aloud?

“Oh,” said Coraline to Miss Spink. “Mister Bobo. Right. Well,” she said, a little louder, “I’m going to go and play with my dolls now, over by the old tennis court, round the back.”

“That’s nice, dear,” said Miss Spink. Then she added confidentially, “Make sure you keep an eye out for the old well. Mister Lovat, who was here before your time, said that he thought it might go down for half a mile or more.”

Coraline hoped that the hand had not heard this last, and she changed the subject. “This key?” said Coraline loudly. “Oh, it’s just some old key from our house. It’s part of my game. That’s why I’m carrying it around with me on this piece of string. Well, good-bye now.”

“What an extraordinary child,” said Miss Spink to herself as she closed the door.

Coraline ambled across the meadow toward the old tennis court, dangling and swinging the black key on its piece of string as she walked.

Several times she thought she saw something the color of bone in the undergrowth. It was keeping pace with her, about thirty feet away.

She tried to whistle, but nothing happened, so she sang out loud instead, a song her father had made up for her when she was a little baby and which had always made her laugh. It went,

Oh—my twitchy witchy girl

I think you are so nice,

I give you bowls of porridge

And I give you bowls of ice

Cream.

I give you lots of kisses,

And I give you lots of hugs,

But I never give you sandwiches

With bugs

In.

That was what she sang as she sauntered through the woods, and her voice hardly trembled at all.

The dolls’ tea party was where she had left it. She was relieved that it was not a windy day, for everything was still in its place, every water-filled plastic cup weighed down the paper tablecloth as it was meant to. She breathed a sigh of relief.

Now was the hardest part.

“Hello dolls,” she said brightly. “It’s teatime!”

She walked close to the paper tablecloth. “I brought the lucky key,” she told the dolls, “to make sure we have a good picnic.”

And then, as carefully as she could, she leaned over and, gently, placed the key on the tablecloth. She was still holding on to the string. She held her breath, hoping that the cups of water at the edges of the well would weigh the cloth down, letting it take the weight of the key without collapsing into the well.

The key sat in the middle of the paper picnic cloth. Coraline let go of the string, and took a step back. Now it was all up to the hand.

She turned to her dolls.

“Who would like a piece of cherry cake?” she asked. “Jemima? Pinky? Primrose?” and she served each doll a slice of invisible cake on an invisible plate, chattering happily as she did so.

From the corner of her eye she saw something bone white scamper from one tree trunk to another, closer and closer. She forced herself not to look at it.

“Jemima!” said Coraline. “What a bad girl you are! You’ve dropped your cake! Now I’ll have to go over and get you a whole new slice!” And she walked around the tea party until she was on the other side of it to the hand. She pretended to clean up spilled cake, and to get Jemima another piece.

And then, in a skittering, chittering rush, it came. The hand, running high on its fingertips, scrabbled through the tall grass and up onto a tree stump. It stood there for a moment, like a crab tasting the air, and then it made one triumphant, nail-clacking leap onto the center of the paper tablecloth.

Time slowed for Coraline. The white fingers closed around the black key. . . .

And then the weight and the momentum of the hand sent the plastic dolls’ cups flying, and the paper tablecloth, the key, and the other mother’s right hand went tumbling down into the darkness of the well.

Coraline counted slowly under her breath. She got up to forty before she heard a muffled splash coming from a long way below.

Someone had once told her that if you look up at the sky from the bottom of a mine shaft, even in the brightest daylight, you see a night sky and stars. Coraline wondered if the hand could see stars from where it was.

She hauled the heavy planks back onto the well, covering it as carefully as she could. She didn’t want anything to fall in. She didn’t want anything ever to get out.

Then she put her dolls and the cups back in the cardboard box she had carried them out in. Something caught her eye while she was doing this, and she straightened up in time to see the black cat stalking toward her, its tail held high and curling at the tip like a question mark. It was the first time she had seen the cat in several days, since they had returned together from the other mother’s place.

The cat walked over to her and jumped up onto the planks that covered the well. Then, slowly, it winked one eye at her.

It sprang down into the long grass in front of her, and rolled over onto its back, wiggling about ecstatically.

Coraline scratched and tickled the soft fur on its belly, and the cat purred contentedly. When it had had enough it rolled over onto its front once more and walked back toward the tennis court, like a tiny patch of midnight in the midday sun.

Coraline went back to the house.

Mr. Bobo was waiting for her in the driveway. He clapped her on the shoulder.

“The mice tell me that all is good,” he said. “They say that you are our savior, Caroline.”

“It’s Coraline, Mister Bobo,” said Coraline. “Not Caroline. Coraline.”

“Coraline,” said Mr. Bobo, repeating her name to himself with wonderment and respect. “Very good, Coraline. The mice say that I must tell you that as soon as they are ready to perform in public, you will come up and watch them as the first audience of all. They will play tumpty umpty and toodle oodle, and they will dance, and do a thousand tricks. That is what is they say.”

“I would like that very much,” said Coraline. “When they’re ready.”

She knocked at Miss Spink and Miss Forcible’s door. Miss Spink let her in and Coraline went into their parlor. She put her box of dolls down on the floor. Then she put her hand into her pocket and pulled out the stone with the hole in it.

“Here you go,” she said. “I don’t need it anymore. I’m very grateful. I think it may have saved my life, and saved some other people’s death.”

She gave them both tight hugs, although her arms barely stretched around Miss Spink, and Miss Forcible smelled like the raw garlic she had been cutting. Then Coraline picked up her box of dolls and went out.

“What an extraordinary child,” said Miss Spink. No one had hugged her like that since she had retired from the theater.

That night Coraline lay in bed, all bathed, teeth cleaned, with her eyes open, staring up at the ceiling.

It was warm enough that, now that the hand was gone, she had opened her bedroom window wide. She had in-sisted to her father that the curtains not be entirely closed.

Her new school clothes were laid out carefully on her chair for her to put on when she woke.

Normally, on the night before the first day of term, Coraline was apprehensive and nervous. But, she realized, there was nothing left about school that could scare her anymore.

She fancied she could hear sweet music on the night air: the kind of music that can only be played on the tiniest silver trombones and trumpets and bassoons, on piccolos and tubas so delicate and small that their keys could only be pressed by the tiny pink fingers of white mice.

Coraline imagined that she was back again in her dream, with the two girls and the boy under the oak tree in the meadow, and she smiled.

As the first stars came out Coraline finally allowed herself to drift into sleep, while the gentle upstairs music of the mouse circus spilled out onto the warm evening air, telling the world that the summer was almost done.

INTRODUCTION

I T WOULD HAVE BEEN easy to put together an “unseen material” section on American Gods, my last novel. Once the book was done, there were about ten thousand words ready to be cut. There was a whole short story that didn’t seem to belong in the book, so I wound up sending it out as a very wordy Christmas card. That wasn’t going to happen with Coraline. I wrote it very slowly, a word at a time, making, unintentionally, something that left no room for cuts and elisions.

I only removed one bit from the whole thing; many years ago I showed it to a very eminent and brilliant author, who wanted to publish it in her line of books, but who felt that it needed something at the beginning to tell you what sort of a book it was.

This is the story of Coraline, I wrote, who was small for her age, and found herself in darkest danger.

Before it was all over Coraline had seen what lay behind mirrors, and had a close call with a bad hand, and had come face to face with her other mother; she had rescued her true parents from a fate worse than death and triumphed against overwhelming odds.

This is the story of Coraline, who lost her parents, and found them again, and (more or less) escaped (more or less) unscathed.

But the author’s career as a publisher was pretty much over, and when, some years after that, I sat down to write the last two-thirds of the book (in August 1992 I’d got up to “Hullo,” said Coraline. “How did you get in?” The cat didn’t say anything. Coraline got out of bed and then stopped, without ending the sentence, for six years), the first thing I did was to remove that opening.

Date: 2015-12-11; view: 1352

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| WHY I WROTE CORALINE 5 page | | | WHY I WROTE CORALINE 7 page |