CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

WHY I WROTE CORALINE 5 page

“Well,” said Coraline to the thing that had once been her other father, “at least you didn’t jump out at me.”

The creature’s twiglike hands moved to its face and pushed the pale clay about, making something like a nose. It said nothing.

“I’m looking for my parents,” said Coraline. “Or a stolen soul from one of the other children. Are they down here?”

“There is nothing down here,” said the pale thing indistinctly. “Nothing but dust and damp and forgetting.” The thing was white, and huge, and swollen. Monstrous, thought Coraline, but also miserable. She raised the stone with the hole in it to her eye and looked through it. Nothing. The pale thing was telling her the truth.

“Poor thing,” she said. “I bet she made you come down here as a punishment for telling me too much.”

The thing hesitated, then it nodded. Coraline wondered how she could ever have imagined that this grublike thing resembled her father.

“I’m so sorry,” she said.

“She’s not best pleased,” said the thing that was once the other father. “Not best pleased at all. You’ve put her quite out of sorts. And when she gets out of sorts, she takes it out on everybody else. It’s her way.”

Coraline patted its hairless head. Its skin was tacky, like warm bread dough. “Poor thing,” she said. “You’re just a thing she made and then threw away.”

The thing nodded vigorously; as it nodded, the left button eye fell off and clattered onto the concrete floor. The thing looked around vacantly with its one eye, as if it had lost her. Finally it saw her, and, as if making a great effort, it opened its mouth once more and said in a wet, urgent voice, “Run, child. Leave this place. She wants me to hurt you, to keep you here forever, so that you can never finish the game and she will win. She is pushing me so hard to hurt you. I cannot fight her.”

“You can,” said Coraline. “Be brave.”

She looked around: the thing that had once been the other father was between her and the steps up and out of the cellar. She started edging along the wall, heading toward the steps. The thing twisted bonelessly until its one eye was again facing her. It seemed to be getting bigger, now, and more awake. “Alas,” it said, “I cannot.”

And it lunged across the cellar toward her then, its toothless mouth opened wide.

Coraline had a single heartbeat in which to react. She could only think of two things to do. Either she could scream and try to run away, and be chased around a badly lit cellar by the huge grub thing, be chased until it caught her. Or she could do something else.

So she did something else.

As the thing reached her, Coraline put out her hand and closed it around the thing’s remaining button eye, and she tugged as hard as she knew how.

For a moment nothing happened. Then the button came away and flew from her hand, clicking against the walls before it fell to the cellar floor.

The thing froze in place. It threw its pale head back blindly, and opened its mouth horribly wide, and it roared its anger and frustration. Then, all in a rush, the thing swept toward the place where Coraline had been standing.

But Coraline was not standing there any longer. She was already tiptoeing, as quietly as she could, up the steps that would take her away from the dim cellar with the crude paintings on the walls. She could not take her eyes from the floor beneath her, though, across which the pale thing flopped and writhed, hunting for her. Then, as if it was being told what to do, the creature stopped moving, and its blind head tipped to one side.

It’s listening for me, thought Coraline. I must be extra quiet. She took another step up, and her foot slipped on the step, and the thing heard her.

Its head tipped toward her. For a moment it swayed and seemed to be gathering its wits. Then, fast as a serpent, it slithered for the steps and began to flow up them, toward her. Coraline turned and ran, wildly, up the last half dozen steps, and she pushed herself up and onto the floor of the dusty bedroom. Without pausing, she pulled the heavy trapdoor toward her, and let go of it. It crashed down with a thump just as something large banged against it. The trapdoor shook and rattled in the floor, but it stayed where it was.

Coraline took a deep breath. If there had been any furniture in that flat, even a chair, she would have pulled it onto the trapdoor, but there was nothing.

She walked out of that flat as fast as she could, without actually ever running, and she locked the front door behind her. She left the door key under the mat. Then she walked down onto the drive.

She had half expected that the other mother would be standing there waiting for Coraline to come out, but the world was silent and empty.

Coraline wanted to go home.

She hugged herself, and told herself that she was brave, and she almost believed herself, and then she walked around to the side of the house, in the gray mist that wasn’t a mist, and she made for the stairs, to go up.

X.

C ORALINE WALKED UP THE stairs outside the building to the topmost flat, where, in her world, the crazy old man upstairs lived. She had gone up there once with her real mother, when her mother was collecting for charity. They had stood in the open doorway, waiting for the crazy old man with the big mustache to find the envelope that Coraline’s mother had left, and the flat had smelled of strange foods and pipe tobacco and odd, sharp, cheesy-smelling things Coraline could not name. She had not wanted to go any farther inside than that.

“I’m an explorer,” said Coraline out loud, but her words sounded muffled and dead on the misty air. She had made it out of the cellar, hadn’t she?

And she had. But if there was one thing that Coraline was certain of, it was that this flat would be worse.

She reached the top of the house. The topmost flat had once been the attic of the house, but that was long ago.

She knocked on the green-painted door. It swung open, and she walked in.

We have eyes and we have nerveses

We have tails we have teeth

You’ll all get what you deserveses

When we rise from underneath.

whispered a dozen or more tiny voices, in that dark flat with the roof so low where it met the walls that Coraline could almost reach up and touch it.

Red eyes stared at her. Little pink feet scurried away as she came close. Darker shadows slipped through the shadows at the edges of things.

It smelled much worse in here than in the real crazy old man upstairs’s flat. That smelled of food (unpleasant food, to Coraline’s mind, but she knew that was a matter of taste: she did not like spices, herbs, or exotic things). This place smelled as if all the exotic foods in the world had been left out to go rotten.

“Little girl,” said a rustling voice in a far room.

“Yes,” said Coraline. I’m not frightened, she told herself, and as she thought it she knew that it was true. There was nothing here that frightened her. These things—even the thing in the cellar—were illusions, things made by the other mother in a ghastly parody of the real people and real things on the other end of the corridor. She could not truly make anything, decided Coraline. She could only twist and copy and distort things that already existed.

And then Coraline found herself wondering why the other mother would have placed a snowglobe on the drawing-room mantelpiece; for the mantelpiece, in Coraline’s world, was quite bare.

As soon as she had asked herself the question, she realized that there was actually an answer.

Then the voice came again, and her train of thought was interrupted.

“Come here, little girl. I know what you want, little girl.” It was a rustling voice, scratchy and dry. It made Coraline think of some kind of enormous dead insect. Which was silly, she knew. How could a dead thing, especially a dead insect, have a voice?

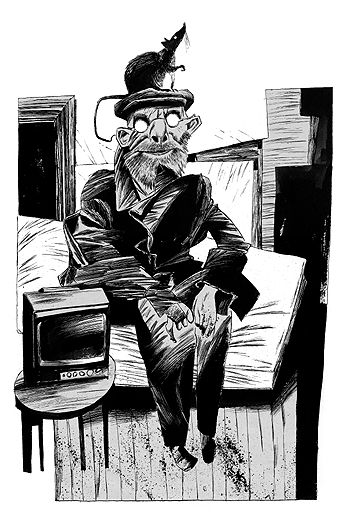

She walked through several rooms with low, slanting ceilings until she came to the final room. It was a bedroom, and the other crazy old man upstairs sat at the far end of the room, in the near darkness, bundled up in his coat and hat. As Coraline entered he began to talk. “Nothing’s changed, little girl,” he said, his voice sounding like the noise dry leaves make as they rustle across a pavement. “And what if you do everything you swore you would? What then? Nothing’s changed. You’ll go home. You’ll be bored. You’ll be ignored. No one will listen to you, not really listen to you. You’re too clever and too quiet for them to understand. They don’t even get your name right.

“Stay here with us,” said the voice from the figure at the end of the room. “We will listen to you and play with you and laugh with you. Your other mother will build whole worlds for you to explore, and tear them down every night when you are done. Every day will be better and brighter than the one that went before. Remember the toy box? How much better would a world be built just like that, and all for you?”

“And will there be gray, wet days where I just don’t know what to do and there’s nothing to read or to watch and nowhere to go and the day drags on forever?” asked Coraline.

From the shadows, the man said, “Never.”

“And will there be awful meals, with food made from recipes, with garlic and tarragon and broad beans in?” asked Coraline.

“Every meal will be a thing of joy,” whispered the voice from under the old man’s hat. “Nothing will pass your lips that does not entirely delight you.”

“And could I have Day-Glo green gloves to wear, and yellow Wellington boots in the shape of frogs?” asked Coraline.

“Frogs, ducks, rhinos, octopuses—whatever you desire. The world will be built new for you every morning. If you stay here, you can have whatever you want.”

Coraline sighed. “You really don’t understand, do you?” she said. “I don’t want whatever I want. Nobody does. Not really. What kind of fun would it be if I just got everything I ever wanted? Just like that, and it didn’t mean anything. What then?”

“I don’t understand,” said the whispery voice.

“Of course you don’t understand,” she said, raising the stone with the hole in it to her eye. “You’re just a bad copy she made of the crazy old man upstairs.”

“Not even that anymore,” said the dead, whispery voice. There was a glow coming from the raincoat of the man, at about chest height. Through the hole in the stone the glow twinkled and shone blue-white as any star. She wished she had a stick or something to poke him with: she had no wish to get any closer to the shadowy man at the end of the room.

Coraline took a step closer to the man, and he fell apart. Black rats leapt from the sleeves and from under the coat and hat, a score or more of them, red eyes shining in the dark. They chittered and they fled. The coat fluttered and fell heavily to the floor. The hat rolled into one corner of the room.

Coraline reached out one hand and pulled the coat open. It was empty, although it was greasy to the touch. There was no sign of the final glass marble in it. She scanned the room, squinting through the hole in the stone, and caught sight of something that twinkled and burned like a star at floor level by the doorway. It was being carried in the forepaws of the largest black rat. As she looked, it slipped away.

The other rats watched her from the corners of the rooms as she ran after it.

Now, rats can run faster than people, especially over short distances. But a large black rat holding a marble in its two front paws is no match for a determined girl (even if she is small for her age) moving at a run. Smaller black rats ran back and forth across her path, trying to distract her, but she ignored them all, keeping her eyes fixed on the one with the marble, who was heading straight out of the flat, toward the front door.

They reached the steps on the outside of the building.

Coraline had time to observe that the house itself was continuing to change, becoming less distinct and flattening out, even as she raced down the stairs. It reminded her of a photograph of a house, now, not the thing itself. Then she was simply racing pell-mell down the steps in pursuit of the rat, with no room in her mind for anything else, certain she was gaining on it. She was running fast—too fast, she discovered, as she came to the bottom of one flight of stairs, and her foot skidded and twisted and she went crashing onto the concrete landing.

Her left knee was scraped and skinned, and the palm of one hand she had thrown out to stop herself was a mess of scraped skin and grit. It hurt a little, and it would, she knew, soon hurt much more. She picked the grit out of her palm and climbed to her feet and, as fast as she could, knowing that she had lost and it was already too late, she went down to the final landing at the ground level.

She looked around for the rat, but it was gone, and the marble with it.

Her hand stung where the skin had been scraped, and there was blood trickling down her ripped pajama leg from her knee. It was as bad as the summer that her mother had taken the training wheels off Coraline’s bicycle; but then, back then, in with all the cuts and scrapes (her knees had had scabs on top of scabs) she had had a feeling of achievement. She was learning something, doing something she had not known how to do. Now she felt nothing but cold loss. She had failed the ghost children. She had failed her parents. She had failed herself, failed everything.

She closed her eyes and wished that the earth would swallow her up.

There was a cough.

She opened her eyes and saw the rat. It was lying on the brick path at the bottom of the stairs with a surprised look on its face—which was now several inches away from the rest of it. Its whiskers were stiff, its eyes were wide open, its teeth visible and yellow and sharp. A collar of wet blood glistened at its neck.

Beside the decapitated rat, a smug expression on its face, was the black cat. It rested one paw on the gray glass marble.

“I think I once mentioned,” said the cat, “that I don’t like rats at the best of times. It looked like you needed this one, however. I hope you don’t mind my getting involved.”

“I think,” said Coraline, trying to catch her breath, “I think you may—have said—something of the sort.”

The cat lifted its paw from the marble, which rolled toward Coraline. She picked it up. In her mind a final voice whispered to her, urgently.

“She has lied to you. She will never give you up, now she has you. She will no more give any of us up than change her nature.” The hairs on the back of Coraline’s neck prickled, and Coraline knew that the girl’s voice told the truth. She put the marble in her dressing-gown pocket with the others.

She had all three marbles, now.

All she needed to do was to find her parents.

And, Coraline realized with surprise, that bit was easy. She knew exactly where her parents were. If she had stopped to think, she might have known where they were all along. The other mother could not create. She could only transform, and twist, and change.

The mantelpiece in the drawing room back home was quite empty. But knowing that, she knew something else as well.

“The other mother. She plans to break her promise. She won’t let us go,” said Coraline.

“I wouldn’t put it past her,” admitted the cat. “Like I said, there’s no guarantee she’ll play fair.” And then he raised his head. “Hullo . . . did you see that?”

“What?”

“Look behind you,” said the cat.

The house had flattened out even more. It no longer looked like a photograph—more like a drawing, a crude, charcoal scribble of a house drawn on gray paper.

“Whatever’s happening,” said Coraline, “thank you for helping with the rat. I suppose I’m almost there, aren’t I? So you go off into the mist or wherever you go, and I’ll, well, I hope I get to see you at home. If she lets me go home.”

The cat’s fur was on end, and its tail was bristling like a chimney sweep’s brush.

“What’s wrong?” asked Coraline.

“They’ve gone,” said the cat. “They aren’t there anymore. The ways in and out of this place. They just went flat.”

“Is that bad?”

The cat lowered its tail, swishing it from side to side angrily. It made a low growling noise in the back of its throat. It walked in a circle, until it was facing away from Coraline, and then it began to walk backwards, stiffly, one step at a time, until it was pushing up against Coraline’s leg. She put down a hand to stroke it, and could feel how hard its heart was beating. It was trembling like a dead leaf in a storm.

“You’ll be fine,” said Coraline. “Everything’s going to be fine. I’ll take you home.”

The cat said nothing.

“Come on, cat,” said Coraline. She took a step back toward the steps, but the cat stayed where it was, looking miserable and, oddly, much smaller.

“If the only way out is past her,” said Coraline, “then that’s the way we’re going to go.” She went back to the cat, bent down, and picked it up. The cat did not resist. It simply trembled. She supported its bottom with one hand, rested its front legs on her shoulders. The cat was heavy but not too heavy to carry. It licked at the palm of her hand, where the blood from the scrape was welling up.

Coraline walked up the stairs one step at a time, heading back to her own flat. She was aware of the marbles clicking in her pocket, aware of the stone with a hole in it, aware of the cat pressing itself against her.

She got to her front door—now just a small child’s scrawl of a door—and she pushed her hand against it, half expecting that her hand would rip through it, revealing nothing behind it but blackness and a scattering of stars.

But the door swung open, and Coraline went through.

XI.

O NCE INSIDE, IN HER FLAT, or rather, in the flat that was not hers, Coraline was pleased to see that it had not transformed into the empty drawing that the rest of the house seemed to have become. It had depth, and shadows, and someone who stood in the shadows waiting for Coraline to return.

“So you’re back,” said the other mother. She did not sound pleased. “And you brought vermin with you.”

“No,” said Coraline. “I brought a friend,” She could feel the cat stiffening under her hands, as if it were anxious to be away. Coraline wanted to hold on to it like a teddy bear, for reassurance, but she knew that cats hate to be squeezed, and she suspected that frightened cats were liable to bite and scratch if provoked in any way, even if they were on your side.

“You know I love you,” said the other mother flatly.

“You have a very funny way of showing it,” said Coraline. She walked down the hallway, then turned into the drawing room, steady step by steady step, pretending that she could not feel the other mother’s blank black eyes on her back. Her grandmother’s formal furniture was still there, and the painting on the wall of the strange fruit (but now the fruit in the painting had been eaten, and all that remained in the bowl was the browning core of an apple, several plum and peach stones, and the stem of what had formerly been a bunch of grapes). The lion-pawed table raked the carpet with its clawed wooden feet, as if it were impatient for something. At the end of the room, in the corner, stood the wooden door, which had once, in another place, opened onto a plain brick wall. Coraline tried not to stare at it. The window showed nothing but mist.

This was it, Coraline knew. The moment of truth. The unraveling time.

The other mother had followed her in. Now she stood in the center of the room, between Coraline and the mantelpiece, and looked down at Coraline with black button eyes. It was funny, Coraline thought. The other mother did not look anything at all like her own mother. She wondered how she had ever been deceived into imagining a resemblance. The other mother was huge—her head almost brushed the ceiling—and very pale, the color of a spider’s belly. Her hair writhed and twined about her head, and her teeth were sharp as knives. . . .

“Well?” said the other mother sharply. “Where are they?”

Coraline leaned against an armchair, adjusted the cat with her left hand, put her right hand into her pocket, and pulled out the three glass marbles. They were a frosted gray, and they clinked together in the palm of her hand. The other mother reached her white fingers for them, but Coraline slipped them back into her pocket. She knew it was true, then. The other mother had no intention of letting her go or of keeping her word. It had been an entertainment, and nothing more. “Hold on,” she said. “We aren’t finished yet, are we?”

The other mother looked daggers, but she smiled sweetly. “No,” she said. “I suppose not. After all, you still need to find your parents, don’t you?”

“Yes,” said Coraline. I must not look at the mantelpiece, she thought. I must not even think about it.

“Well?” said the other mother. “Produce them. Would you like to look in the cellar again? I have some other interesting things hidden down there, you know.”

“No,” said Coraline. “I know where my parents are.” The cat was heavy in her arms. She moved it forward, unhooking its claws from her shoulder as she did so.

“Where?”

“It stands to reason,” said Coraline. “I’ve looked everywhere you’d hide them. They aren’t in the house.”

The other mother stood very still, giving nothing away, lips tightly closed. She might have been a wax statue. Even her hair had stopped moving.

“So,” Coraline continued, both hands wrapped firmly around the black cat. “I know where they have to be. You’ve hidden them in the passageway between the houses, haven’t you? They are behind that door.” She nodded her head toward the door in the corner.

The other mother remained statue still, but a hint of a smile crept back onto her face. “Oh, they are, are they?”

“Why don’t you open it?” said Coraline. “They’ll be there, all right.”

It was her only way home, she knew. But it all depended on the other mother’s needing to gloat, needing not only to win but to show that she had won.

The other mother reached her hand slowly into her apron pocket and produced the black iron key. The cat stirred uncomfortably in Coraline’s arms, as if it wanted to get down. Just stay there for a few moments longer, she thought at it, wondering if it could hear her. I’ll get us both home. I said I would. I promise. She felt the cat relax ever so slightly in her arms.

The other mother walked over to the door and pushed the key into the lock.

She turned the key.

Coraline heard the mechanism clunk heavily. She was already starting, as quietly as she could, step by step, to back away toward the mantelpiece.

The other mother pushed down on the door handle and pulled open the door, revealing a corridor behind it, dark and empty. “There,” she said, waving her hands at the corridor. The expression of delight on her face was a very bad thing to see. “You’re wrong! You don’t know where your parents are, do you? They aren’t there.” She turned and looked at Coraline. “Now,” she said, “you’re going to stay here for ever and always.”

“No,” said Coraline. “I’m not.” And, hard as she could, she threw the black cat toward the other mother. It yowled and landed on the other mother’s head, claws flailing, teeth bared, fierce and angry. Fur on end, it looked half again as big as it was in real life.

Without waiting to see what would happen, Coraline reached up to the mantlepiece and closed her hand around the snow globe, pushing it deep into the pocket of her dressing gown.

The cat made a deep, ululating yowl and sank its teeth into the other mother’s cheek. She was flailing at it. Blood ran from the cuts on her white face—not red blood but a deep, tarry black stuff. Coraline ran for the door.

She pulled the key out of the lock.

“Leave her! Come on!” she shouted to the cat. It hissed, and swiped its scalpel-sharp claws at the other mother’s face in one wild rake which left black ooze trickling from several gashes on the other mother’s nose. Then it sprang down toward Coraline. “Quickly!” she said. The cat ran toward her, and they both stepped into the dark corridor.

It was colder in the corridor, like stepping down into a cellar on a warm day. The cat hesitated for a moment; then, seeing the other mother was coming toward them, it ran to Coraline and stopped by her legs.

Coraline began to pull the door closed.

It was heavier than she imagined a door could be, and pulling it closed was like trying to close a door against a high wind. And then she felt something from the other side starting to pull against her.

Shut! she thought. Then she said, out loud, “Come on, please.” And she felt the door begin to move, to pull closed, to give against the phantom wind.

Suddenly she was aware of other people in the corridor with her. She could not turn her head to look at them, but she knew them without having to look. “Help me, please,” she said. “All of you.”

The other people in the corridor—three children, two adults—were somehow too insubstantial to touch the door. But their hands closed about hers, as she pulled on the big iron door handle, and suddenly she felt strong.

“Never let up, Miss! Hold strong! Hold strong!” whispered a voice in her mind.

“Pull, girl, pull!” whispered another.

And then a voice that sounded like her mother’s—her own mother, her real, wonderful, maddening, infuriating, glorious mother—just said, “Well done, Coraline,” and that was enough.

The door started to slip closed, easily as anything.

“No!” screamed a voice from beyond the door, and it no longer sounded even faintly human.

Something snatched at Coraline, reaching through the closing gap between the door and the doorpost. Coraline jerked her head out of the way, but the door began to open once more.

“We’re going to go home,” said Coraline. “We are. Help me.” She ducked the snatching fingers.

They moved through her, then: ghost hands lent her strength that she no longer possessed. There was a final moment of resistance, as if something were caught in the door, and then, with a crash, the wooden door banged closed.

Something dropped from Coraline’s head height to the floor. It landed with a sort of a scuttling thump.

“Come on!” said the cat. “This is not a good place to be in. Quickly.”

Coraline turned her back on the door and began to run, as fast as was practical, through the dark corridor, running her hand along the wall to make sure she didn’t bump into anything or get turned around in the darkness.

It was an uphill run, and it seemed to her that it went on for a longer distance than anything could possibly go. The wall she was touching felt warm and yielding now, and, she realized, it felt as it were covered in a fine downy fur. It moved, as if it were taking a breath. She snatched her hand away from it.

Winds howled in the dark.

She was scared she would bump into something, and she put out her hand for the wall once more. This time what she touched felt hot and wet, as if she had put her hand in somebody’s mouth, and she pulled it back with a small wail.

Her eyes had adjusted to the dark. She could half see, as faintly glowing patches ahead of her, two adults, three children. She could hear the cat, too, padding in the dark in front of her.

And there was something else, which suddenly scuttled between her feet, nearly sending Coraline flying. She caught herself before she went down, using her own momentum to keep moving. She knew that if she fell in that corridor she might never get up again. Whatever that corridor was was older by far than the other mother. It was deep, and slow, and it knew that she was there. . . .

Then daylight appeared, and she ran toward it, puffing and wheezing. “Almost there,” she called encouragingly, but in the light she discovered that the wraiths had gone, and she was alone. She did not have time to wonder what had happened to them. Panting for breath, she staggered through the door, and slammed it behind her with the loudest, most satisfying bang you can imagine.

Coraline locked the door with the key, and put the key back into her pocket.

The black cat was huddled in the farthest corner of the room, the pink tip of its tongue showing, its eyes wide. Coraline went over to it and crouched down beside it.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I’m sorry I threw you at her. But it was the only way to distract her enough to get us all out. She would never have kept her word, would she?”

The cat looked up at her, then rested its head on her hand, licking her fingers with its sandpapery tongue. It began to purr.

“Then we’re friends?” said Coraline.

She sat down on one of her grandmother’s uncomfortable armchairs, and the cat sprang up into her lap and made itself comfortable. The light that came through the picture window was daylight, real golden late-afternoon daylight, not a white mist light. The sky was a robin’s-egg blue, and Coraline could see trees and, beyond the trees, green hills, which faded on the horizon into purples and grays. The sky had never seemed so sky, the world had never seemed so world.

Date: 2015-12-11; view: 1290

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| WHY I WROTE CORALINE 4 page | | | WHY I WROTE CORALINE 6 page |