CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Schumpeter

While the concept of dubbing movies is alien to many British and American cinemagoers, it still remains de rigueur in many parts of Europe. The regular voice artists who dub for the likes of Bruce Willis or Tom Cruise can become stars themselves, writes Ross Davies.

Maybe it's as a cultural consequence of the myriad kung fu films spawned in the 1970s and 1980s, but it's easy for a Briton or American to think of dubbing as a kind of amateurish cottage industry, replete with inaccurate dialogue and risible out-of-synch diction.

Imagine watching a European art house film, for instance, only to have your ears met with the voice of, say, Danny Dyer. For most people it would present a jarring asymmetry. An audio-visual lopsidedness, if you will.

After all, the reason Britons and Americans often watch foreign films - apart from to flex our culture vulture credentials in front of friends and colleagues - is for the exoticism of viewing another culture in action.

Language, in its original context, plays a huge part of that experience.

With Michael Haneke's Amour up for best picture at this weekend's Oscars, it would appear that many of us cinephiles, who happen to list English as our mother tongue, are still more than happy with the standard conduit of subtitles.

The goal is that the audience thinks that Daniel Craig actually speaks German”

DietmarWunder German voice of James Bond

Yet, on the continent, the dubbing of foreign films is still very common. And the voice actors, who may "do" one or multiple actors, are recognised as celebrities in their own right.

But just how does one become a dubber?

For the last seven years, DietmarWunder has been the official "voice" of Daniel Craig in the revamped James Bond canon. Like many other voice artists, he is a trained actor who inadvertently stumbled into the industry.

"I was actually doing some theatre when a colleague of mine, who happened to be a dubbing director, gave me my first role as stuttering student in Happy Days. Initially, it was pretty challenging but I haven't looked back since."

Wunder's enthusiasm for his profession isn't surprising. It has afforded him a comfortable lifestyle, including a red carpet welcome at last year's German premiere of Skyfall.

He is quick to stress that dubbing is more than just simply reading off a script in a studio.

"You need to really follow the performance of the actor on the screen to remain believable," he says. "That means mimicking his movements so that they become your own. The goal is that the audience thinks that Daniel Craig actually speaks German."

DietmarWunder is the voice of Daniel Craig in the German trailer for Skyfall

Like Wunder, Luca Biagini was a theatre actor before he entered a dubbing set in Italy which dates back to the days of Mussolini when foreign films had to be re-voiced in Italian.

In the last 30 years, he has dubbed everyone from John Malkovich and Harrison Ford to Downton Abbey's Hugh Bonneville.

In 2010, he also lent his intonation to the Italian version of The King's Speech, doubling up for Colin Firth's Oscar-winning turn as George VI.

Effecting and synchronising a stutter was particularly challenging, says Biagini.

"It's a role that is close to my heart, but it wasn't easy. The aim was to recreate the voice without the viewer being aware of any synchronisation - a bit like magic or an illusion. Having the guidance of an intelligent director also helped."

The dubbing process is a lot more complex than many would imagine.

The interpretation often requires a cabal of translators, adaptors, actors and a specialist dubbing director. It's a rigorous process, says Italian actress Lisa Genovese.

Currently residing in London, Genovese started out her career as an assistant to director Mario Maldesi, the self-styled doyen of Italian dubbing, notably cherry-picked by Stanley Kubrick to synchronise the dialogue from his 1972 film A Clockwork Orange.

"He was amazing , a maestro , but he could be hard work," she explains. "I remember he once called in this actress to do a very tiny part, but she ended up having to recite her lines twenty times before Mario was satisfied. Wealllearnedsomuchfromhim."

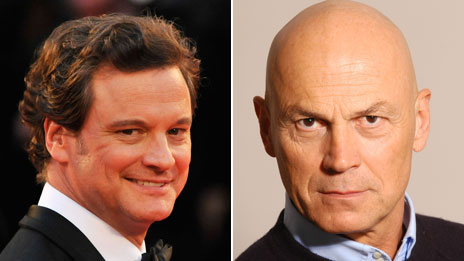

Luca Biagini provides the voice of Colin Firth in The King's Speech - but do they sound similar?

While Biagini and Genovese speak romantically of the artistry required to be successful voice actor, Manfred Lehmann is less effusive.

The German "voice" of Bruce Willis for the last 25 years, he doesn't mince his words when asked what he enjoys most about his job.

"I enjoy the money. It pays the bills."

Armed with a sonorous voice that exudes hard-boiled machismo, it's easy to understand why Lehmann has been cast as the vocal accompaniment to a string of action heroes over his career, including Mickey Rourke, Dolph Lundgren and Steven Seagal, among others.

However, for his home audience, Lehman is inextricably linked to Willis - himself born to a German mother.

When we speak on the phone, he has just finished recording his lines for A Good Day to Die Hard. So, has he ever met his cinematic counterpart?

"About ten years ago," he answers. "I found him to be a pretty nice guy, although we only exchanged pleasantries. I asked him whether he had ever heard my version of him."

One of these men set hearts aflutter as Mr Darcy in Pride and Prejudice

Andhadhe?

"No."

But dubbers have been known to receive recognition and gratitude.

After winning an Oscar in 1998 for his performance in Good Will Hunting, Robin Williams sent his usual German dubbing voice, Peer Augustinski, a note which read: "Thank you for making me famous in Germany."

Biagini has also crossed paths with his matching parts.

"I met Richard Dreyfuss after we had done Mr Holland's Opus and he dubbed me for a joke. I also met Willem Dafoe , who was really gentle and quite reserved. Wegotonwell.

"There was also talk that Hugh Laurie personally selected me as his voice double in House, but I don't know about that - you'll have to ask him."

Not all countries choose rerecording over subtitles.

Brave was dubbed into Icelandic - spoken with Scottish accents

While ubiquitous in Germany and Italy, as well as Spain and France, in Nordic countries, where good English is widely spoken, dubbing only tends to be found across a few children's television programmes.

The argument against subtitles, according to Lehmann, is that "they are a visual distraction, deflecting attention from the film".

Yet, a recent article published in the Italian daily newspaper La Repubblica reported a growing demand among the public for original language films, citing the influence of increased online streaming, television channels with multilingual options and a greater knowledge of English among the younger generation.

However, Genovese is sceptical of a U-turn happening in the near future.

"I am not sure that Italian audiences are ready for films with subtitles," she says. "You have to remember there is a long-standing tradition of dubbing that people are used to. I can't see it being uprooted anytime soon."

Biagini agrees.

"Sure, the audience now has the chance to see a film in its original language, but it is quite elite. The general public still prefers dubbing - for my sake, I hope it does."

Schumpeter

Fixing the capitalist machine

Some sensible ideas for reviving America’s entrepreneurial spirit

Sep 29th 2012 |From the print edition

AMERICA has been the world’s most important growth machine since the second world war. In the 1950s and 1960s its GDP grew by 3% a year despite the economy’s maturity. In the 1970s it endured stagflation but the Reagan revolution revived the entrepreneurial spirit and the growth rate returned to 3% in the 1990s. The machine was good for the world as well as America—it helped spread the gospel of capitalism and transform the American dream into a global dream.

Today the growth machine is in trouble. It all but exploded in the financial crisis of 2007-08. But even before then it had been juddering. Examine the machine’s three most powerful pistons—capital markets, innovation and the knowledge economy—and you discover that they had been malfunctioning for a decade.

The United States once boasted the world’s most business-friendly capital markets. But in recent years the boast has rung hollow, as Robert Litan and Carl Schramm point out in a new book, “Better Capitalism”. Venture capitalists have slashed their spending, dumping more adventurous companies in the process, not least because around 90% of them failed to produce a positive return. The number of initial public offerings is down from an average of 547 a year in the 1990s to 192 since then. This has dramatically cut the supply of new, high-growth companies. Given that companies less than five years old may have provided almost all the 40m net jobs the American economy added between 1980 and the financial crisis, that is dismal news for the unemployed.

America also used to have one of the most business-friendly immigration policies. Fully 18% of the Fortune 500 list as of 2010 were founded by immigrants (among them AT&T, DuPont, eBay, Google, Kraft, Heinz and Procter & Gamble). Include the children of immigrants and the figure is 40%. Immigrants founded a quarter of successful high-tech and engineering companies between 1995 and 2005. They obtain patents at twice the rate of American-born people with the same educational credentials. But America’s immigration policies have tightened dramatically over the past decade, a period in which some other rich countries, such as Canada, have continued to woo skilled immigrants, while fabulous new opportunities have opened up in emerging markets like China and India. Why endure America’s visa obstacle course when other countries are laying out the red carpet?

Finally, America has long boasted the world’s most business-friendly universities. One-fifth of American start-ups are linked to universities, and great institutions like Stanford and MIT spawn businesses by the thousand. But the university-business boom seems to be fading. Federal spending on health-related research increased from $20 billion in 1993 to $30 billion in 2008, for example, but the number of new drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration fell from a peak of 50 in 1996 to just 15 in 2008. University technology offices, which legally have first dibs at commercialising the faculty’s ideas, have evolved into clumsy bureaucracies. The average age of researchers given grants by the National Institutes of Health is 50 and rising.

These problems all bear more heavily on entrepreneurs than established companies. Foreign-born entrepreneurs are finding it harder to gain citizenship. Academics are finding it harder to commercialise their ideas. All sorts of entrepreneurs are finding it harder to obtain seed money and to take their companies public. American capitalism is becoming like its European cousin: established firms with the scale and scope to deal with a growing thicket of regulations are doing well, but new companies are withering on the vine or selling themselves to incumbents.

What can be done to reverse this worrying trend? Messrs Litan and Schramm provide detailed answers. They note that the recent JOBS act was a step in the right direction, not least because it suggested that the political elite is beginning to realise the seriousness of the problem. The act exempts new companies, for their first five years, from the onerous Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) regulations (passed in 2002, in response to a spate of corporate scandals). The act quadruples the number of shareholders that private companies can have (from 499 to 2,000) before they have to go public. It removes barriers to crowdfunding. But Messrs Litan and Schramm also have plenty of suggestions of their own.

Some of their ideas are familiar. They suggest that the government should give green cards to all foreigners who come to America to study science, technology, engineering or maths. Some are more innovative. Exchange-traded investment funds, which have gone from nothing a decade ago to a trillion-dollar industry today, leave promising new companies vulnerable to the fickleness of high-frequency traders: so why not let them exclude themselves from such funds’ baskets of shares? SOX is reducing the supply of new companies in the name of protecting investors: so why not let smaller firms opt out of SOX so long as shareholders are duly warned? The authors also argue that university technology offices should lose their monopolies, giving professors more freedom to exploit their innovations.

Date: 2014-12-29; view: 1251

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Hollywood dubbing: The German Bruce Willis and other invisible stars | | | The truth about baby food |