CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Criminal Law and Civil Law

The Canadian Legal System

The nine judges of the Supreme Court of Canada sit in session in Ottawa.

In contrast to the Canadian parliamentary system, which has remained fairly static and unchanged since Victorian times, the Canadian legal system has undergone tremendous evolution over the last century and a half.

Canada’s legal regime is structured according to the so-called Anglo-American tradition, owing to the country’s British colonial roots. The fundamental principles of Canadian law and justice are thus not terribly different from those governing the judicial system of the U.S., U.K, or other nations with a history of British rule. As is the case in those countries, Canada is a nation that recognizes the general principle that laws must be clear and rational, that all accused men are innocent until proven guilty by a neutral judicial system, and that the government’s power over the individual is limited by the national Constitution and certain universal (or God-given, if you prefer) human rights.

Legal History

The evolution of Canadian law basically unfolded in sync with Canada’s evolution as a colony of Britain.

In many Canadian courtrooms, photographs and video cameras are not allowed, so special courtroom artists must be recruited to draw or paint pictures of the proceedings for newspapers the next day.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, “Canada” didn’t really exist, legally speaking. The nation was simply an overseas chunk of British territory, and under the exclusive domain of British law as a result. This changed in the mid 1800s, when Canadian legislatures were established for the first time. Canadian politicians could now make their own laws, which caused the laws of Britain, for the most part, to stop automatically applying to the Canadian colonies. In 1931, Canada officially stopped being a colony of Great Britain (via the Statute of Westminster), and the British parliament lost most of its powers to pass laws for Canada.

There was still one more cord to cut, however, and it was not until 1949 that Britain ceased to be the ultimate authority in Canadian law. Until that year, legal cases from Canadian courts could be appealed to the Judicial Committee of the British House of Lords, which acted as a sort of across-the-pond supreme court. This setup became more embarrassing and unpopular as the 20th century progressed, with the British Lords coming under increasing fire for not knowing or caring much about Canada and just issuing arbitrary rulings that “felt right” regardless of precedent or context. In 1949, this right of appeal to Britain was abolished, making theSupreme Court of Canadathe new highest legal body in the land. Canadian law was finally sovereign.

The Common Law

Though Canada is now fully independent from Britain, British Common Law still applies, as it does in the United States and other former British colonies. Common Law is basically the idea that precedent matters, and that decisions and definitions set down by courts in earlier times still apply to everyone today. Though Canadian judges now have more than enough independent Canadian legal precedent to help them make decisions, it’s not entirely uncommon for judges, when faced with a particularly thorny legal question, to refer back to the judgments of British judges in the colonial period, or even earlier, in order to provide historical context for the purpose of laws or understanding, say, what “libel” is supposed to mean. The famed Magna Carta of 1215, for instance, which first outlined basic principles of English justice, is still considered one of the foundational documents of Canadian Common Law.

The Charter Era

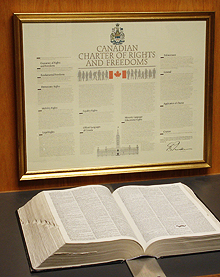

Today, framed copies of the Charter hang in government buildings, libraries, and schools across Canada.

From around 1931 (when Canada became independent from British law) to 1982, Canadian law operated according to a principle known as parliamentary supremacy. According to this theory, with Britain out of the way, there was basically no authority higher than the Canadian Parliament when it came to deciding what was legal and what was not. Any decree passed by Parliament was the law, end of story. If you didn’t like it, too bad.

Parliamentary supremacy ended in 1982, when the Canadian Constitution was reformed and a new thing called the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was added. The Charter declared that some human rights were so important that no law could be passed that violated them. So if, say, the Canadian government passed a law that said all Japanese people had to be rounded up and sent to camps because we were at war with Japan, that law would be unconstitutional, because the Charter forbids parliament from passing a law that discriminates against race or nationality.

1982 thus heralded in a bold new age of Canadian law, sometimes called the “Charter Era.” It’s a new era in which the rights of all Canadians are much more clear and easily protected than in previous decades, but also one in which judges and lawyers have gained a great deal of power, as we shall see.

Criminal Law and Civil Law

The Canadian Constitution delegates the power to make criminal law exclusively to the Parliament of Canada, meaning almost all of Canada’s most “serious” laws are national in scope and apply equally across the entire country. Criminal law is generally understood to involve any effort by the federal government to regulate or maintain public safety, social order or morality. This broad category, in turn, includes all the most glamorous and scary crimes, such as theft, murder, kidnapping, violence, perversion, fraud and corruption. This is the sort of stuff you get thrown in jail for.

All of Canada's significant criminal laws are published yearly in a consolidated volume known as the Pocket Criminal Code. No cop or lawyer should be without one!

Though Canada’s 10 provincial governments have the power to pass laws of their own, these are not allowed to regulate criminal matters and focus largely on the administration of public services such as education, health care, natural resources, transportation and energy or the general regulation of labour and industries. If you break a provincial law, you might be found guilty of a “summary offence,” and get fined or have your business shut down. It’s generally rare to go to prison for a provincial offense.

Federal and provincial laws that affect private, rather than public interests, are known as civil laws. Unlike Canadian criminal laws, which always seek to protect “The Queen” (in the abstract sense of the Queen being the symbolic embodiment of all Canadians), civil laws regulate relationships between individuals and businesses, and civil trials are of the “Peter sues Paul” variety. Most civil laws regulate things such as contracts, property, rent, marriage, child custody, employment and other matters where one person’s interests may run into someone else’s. Canadians are often said to be a people who are quite eager to sue each other over the smallest infractions, and the rise of lawsuits, particularly overtort (negligence) matters has been attributed to the vast amount of civil law in modern Canada.

Law Enforcement

Active-duty RCMP officers usually only wear their famous red outfits on special occasions; the rest of the time they wear more ordinary-looking blue police uniforms. Seen here, Constable Doug Scott (1986-2007) and Superintendent Doug Coates (1957-2010), two famous RCMP heroes who died in the line of duty.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police(RCMP), with their red coats and wide-brimmed hats, are of course one of the most iconic images of Canada, but not all Canadian law enforcement is handled by them. It’s actually up to individual provinces or cities to decide whom they want to recruit to enforce the law and round up troublemakers. The RCMP, which is trained and managed by the federal government, is but one option; there are also a multitude of other local and provincial police forces across the country, including the Ontario Provincial Policewho hold jurisdiction over all of Ontario, and the Vancouver Police Departmentwho run the cops in British Columbia’s largest city.

After arrest comes the trial, and after the trial, can either be fined, put on probation (constant supervision), or thrown in prison. Like the rest of the justice system, Canadian prisons are jointly run by the feds and provinces. Less than two years in prison, and you go to a provincially-run jail. More than two, and it’s federal. Generally speaking, judicial punishments in Canada tend to operate on a progressive scale, and most convicted criminals will only go to jail after repeatedly re-offending.

The most severe punishment in Canada is life in prison. In all other cases, however, imprisoned Canadians are given jail sentences for a specific length of time, and these can be ended early as a reward for personal reform and good prison behaviour, as determined by the local parole board. Canada has had no death penalty since 1976.

Canadian Courts

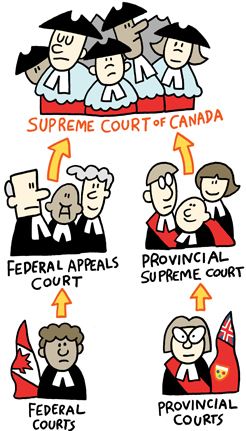

Because criminal law — the most important sort of law — is a federal jurisdiction, the Canadian court system is largely run by the federal government. Though Canada is a federation with power shared between the local and national levels of government, the Canadian justice system is said to be “unitary,” meaning federal and provincial courts are not independent from one another, but rather operate within a single “Canadian” system. The main division is that provincial courts handle all criminalprosecutions and appeals, while federal courts handle disputes involving more esoteric matters of federal jurisdiction, such as conflicts between provinces, maritime law, or disputes over federal taxes or citizenship.

Because criminal law — the most important sort of law — is a federal jurisdiction, the Canadian court system is largely run by the federal government. Though Canada is a federation with power shared between the local and national levels of government, the Canadian justice system is said to be “unitary,” meaning federal and provincial courts are not independent from one another, but rather operate within a single “Canadian” system. The main division is that provincial courts handle all criminalprosecutions and appeals, while federal courts handle disputes involving more esoteric matters of federal jurisdiction, such as conflicts between provinces, maritime law, or disputes over federal taxes or citizenship.

Canadian courtrooms operate in the traditional Anglo-American way. Two lawyers, one representing the accused, one representing the government, argue back and forth, often for several days, in the presence of a judge, who eventually issues a ruling favouring one side over the other. Juries of 12 randomly selected citizens are an optional choice for defendants who would rather not be tried by judge alone. It should be noted that these days full trials are actually quite rare in Canada; the vast majority of Canadians accused of crimes usually arrange a plea bargain — or out-of-court negotiated settlement — with the government in order to secure a faster ruling. This often includespleading guilty to a lesser charge in exchange for the original charges being dropped.

If your trial doesn’t go your way, you can then appeal to various higher courts, who have the power to reconsider the case and reverse the ruling of the previous court. If you appeal enough times, in turn, you wind up at the “court of last resort”.

Date: 2015-12-11; view: 2409

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Organizational Structure | | | The Supreme Court of Canada |