CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Part One. Today

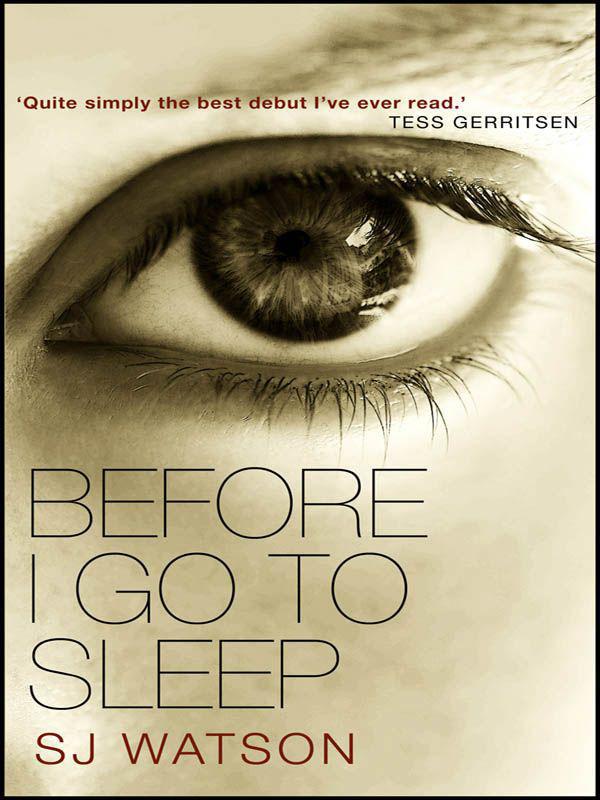

S. J. Watson

Before I Go to Sleep: A Novel

For my mother, and for Nicholas

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Endless gratitude to my wonderful agent, Clare Conville, to Jake Smith‑Bosanquet and all at C&W, and to my editors, Claire Wachtel, Selina Walker, Michael Heyward and Iris Tupholme.

Thanks and love to all my family and friends, for starting me on this journey, for reading early drafts, and for their constant support. Particular thanks to Margaret and Alistair Peacock, Jennifer Hill, Samantha Lear and Simon Graham, who believed in me before I believed in myself, to Andrew Dell, Anzel Britz, Gillian Ib and Jamie Gambino, who came later, and to Nicholas Ib who has been there always. Thanks also to all at GSTT.

Thank you to all at the Faber Academy, and in particular to Patrick Keogh. Finally, this book would not have been written without the input of my gang – Richard Skinner, Amy Cunnah, Damien Gibson, Antonia Hayes, Simon Murphy and Richard Reeves. Huge gratitude for your friendship and support, and long may the FAGs keep control of their feral narrators.

I was born tomorrow

today I live

yesterday killed me

Parviz Owsia

Part One. Today

The bedroom is strange. Unfamiliar. I don’t know where I am, how I came to be here. I don’t know how I’m going to get home.

I have spent the night here. I was woken by a woman’s voice – at first I thought she was in bed with me, but then realized she was reading the news and I was hearing a radio alarm – and when I opened my eyes I found myself here. In this room I don’t recognize.

My eyes adjust and I look around in the near dark. A dressing gown hangs off the back of the wardrobe door – suitable for a woman, but someone much older than I am – and some dark‑coloured trousers are folded neatly over the back of a chair at the dressing table, but I can make out little else. The alarm clock looks complicated, but I find a button and manage to silence it.

It is then that I hear a juddering intake of breath behind me and realize I am not alone. I turn round. I see an expanse of skin and dark hair, flecked with white. A man. He has his left arm outside the covers and there is a gold band on the third finger of the hand. I suppress a groan. So this one is not only old and grey, I think, but also married. Not only have I screwed a married man, but I have done so in what I am guessing is his home, in the bed he must usually share with his wife. I lie back to gather myself. I ought to be ashamed.

I wonder where the wife is. Do I need to worry about her arriving back at any moment? I imagine her standing on the other side of the room, screaming, calling me a slut. A medusa. A mass of snakes. I wonder how I will defend myself, if she does appear. The guy in the bed doesn’t seem concerned, though. He has turned over and snores on.

I lie as still as possible. Usually I can remember how I get into situations like this, but not today. There must have been a party, or a trip to a bar or a club. I must have been pretty wasted. Wasted enough that I don’t remember anything at all. Wasted enough to have gone home with a man with a wedding ring and hairs on his back.

I fold back the covers as gently as I can and sit on the edge of the bed. First, I need to use the bathroom. I ignore the slippers at my feet – after all, fucking the husband is one thing, but I could never wear another woman’s shoes – and creep barefoot on to the landing. I am aware of my nakedness, fearful of choosing the wrong door, of stumbling on a lodger, a teenage son. Relieved, I see the bathroom door is ajar and go in, locking it behind me.

I sit, use the toilet, then flush it and turn to wash my hands. I reach for the soap, but something is wrong. At first I can’t work out what it is, but then I see it. The hand gripping the soap does not look like mine. The skin is wrinkled, the nails are unpolished and bitten to the quick and, like the man in the bed I have just left, the third finger wears a plain, gold wedding ring.

I stare for a moment, then wiggle my fingers. The fingers of the hand holding the soap move also. I gasp, and the soap thuds into the sink. I look up at the mirror.

The face I see looking back at me is not my own. The hair has no volume and is cut much shorter than I wear it, the skin on the cheeks and under the chin sags, the lips are thin, the mouth turned down. I cry out, a wordless gasp that would turn into a shriek of shock were I to let it, and then notice the eyes. The skin around them is lined, yes, but despite everything else I can see that they are mine. The person in the mirror is me, but I am twenty years too old. Twenty‑five. More.

This isn’t possible. Beginning to shake, I grip the edge of the sink. Another scream starts to rise in my chest and this one erupts as a strangled gasp. I step back, away from the mirror, and it is then that I see them. Photographs. Taped to the wall, to the mirror itself. Pictures, interspersed with yellow pieces of gummed paper, felt‑tip notes, damp and curling.

I choose one at random. Christine , it says, and an arrow points to a photograph of me – this new me, this old me – in which I am sitting on a bench on a quayside, next to a man. The name seems familiar, but only distantly so, as if I am having to make an effort to believe that it is mine. In the photograph we are both smiling at the camera, holding hands. He is handsome, attractive, and when I look closely I can see that it is the same man I slept with, the one I left in the bed. The word Ben is written beneath it, and next to it Your husband .

I gasp, and rip it off the wall. No , I think. No! It can’t be … I scan the rest of the pictures. They are all of me, and him. In one I am wearing an ugly dress and unwrapping a present, in another both of us wear matching weatherproof jackets and stand in front of a waterfall as a small dog sniffs at our feet. Next to it is a picture of me sitting beside him, sipping a glass of orange juice, wearing the dressing gown I have seen in the bedroom next door.

I step back further, until I feel cold tiles against my back. It is then I get the glimmer that I associate with memory. As my mind tries to settle on it, it flutters away, like ashes caught in a breeze, and I realize that in my life there is a then, a before, though before what I cannot say, and there is a now, and there is nothing between the two but a long, silent emptiness that has led me here, to me and him, in this house.

I go back into the bedroom. I still have the picture in my hand – the one of me and the man I had woken up with – and I hold it in front of me.

‘What’s going on?’ I say. I am screaming; tears run down my face. The man is sitting up in bed, his eyes half closed. ‘Who are you?’

‘I’m your husband,’ he says. His face is sleepy, without a trace of annoyance. He does not look at my naked body. ‘We’ve been married for years.’

‘What do you mean?’ I say. I want to run, but there is nowhere to go. ‘“Married for years”? What do you mean?’

He stands up. ‘Here,’ he says, and passes me the dressing gown, waiting while I put it on. He is wearing pyjama trousers that are too big for him, a white vest. He reminds me of my father.

‘We got married in nineteen eighty‑five,’ he says. ‘Twenty‑two years ago. You–’

‘What–?’ I feel the blood drain from my face, the room begin to spin. A clock ticks, somewhere in the house, and it sounds as loud as a hammer. ‘But–’ He takes a step towards me. ‘How–?’

‘Christine, you’re forty‑seven now,’ he says. I look at him, this stranger who is smiling at me. I don’t want to believe him, don’t want even to hear what he’s saying, but he carries on. ‘You had an accident,’ he says. ‘A bad accident. You suffered head injuries. You have problems remembering things.’

‘What things?’ I say, meaning, Surely not the last twenty‑five years? ‘What things?’

He steps towards me again, approaching me as if I am a frightened animal. ‘Everything,’ he says. ‘Sometimes starting from your early twenties. Sometimes even earlier than that.’

My mind spins, whirring with dates and ages. I don’t want to ask, but know that I must. ‘When … when was my accident?’

He looks at me, and his face is a mixture of compassion and fear.

‘When you were twenty‑nine …’

I close my eyes. Even as my mind tries to reject this information I know, somewhere, that it is true. I hear myself start to cry again, and as I do so this man, this Ben , comes over to where I stand in the doorway. I feel his presence next to me, do not move as he puts his arms around my waist, do not resist as he pulls me into him. He holds me. Together we rock gently, and I realize the motion feels familiar somehow. It makes me feel better.

‘I love you, Christine,’ he says, and though I know I am supposed to say that I love him too, I don’t. I say nothing. How can I love him? He is a stranger. Nothing makes sense. I want to know so many things. How I got here, how I manage to survive. But I don’t know how to ask.

‘I’m scared,’ I say.

‘I know,’ he replies. ‘I know. But don’t worry, Chris. I’ll look after you. I’ll always look after you. You’ll be fine. Trust me.’

He says he will show me round the house. I feel calmer. I have put on a pair of knickers and an old T‑shirt that he gave me, then put the robe over my shoulders. We go out on to the landing. ‘You’ve seen the bathroom,’ he says, opening the door next to it. ‘This is the office.’

There is a glass desk with what I guess must be a computer, though it looks ridiculously small, almost like a toy. Next to it is a filing cabinet in gunmetal grey, above it a wall planner. All is neat, orderly. ‘I work in there, now and then,’ he says, closing the door. We cross the landing and he opens another door. A bed, a dressing table, more wardrobes. It looks almost identical to the room in which I woke. ‘Sometimes you sleep in here,’ he says, ‘when you feel like it. But usually you don’t like waking up alone. You get panicked when you can’t work out where you are.’ I nod. I feel like a prospective tenant being shown around a new flat. A possible housemate. ‘Let’s go downstairs.’

I follow him down. He shows me a living room – a brown sofa and matching chairs, a flat screen bolted to the wall which he tells me is a television – and a dining room and kitchen. None of it is familiar. I feel nothing at all, not even when I see a framed photograph of the two of us on a sideboard. ‘There’s a garden out the back,’ he says and I look through the glass door that leads off the kitchen. It is just beginning to get light, the night sky starting to turn an inky blue, and I can make out the silhouette of a large tree, and a shed sitting at the far end of the small garden, but little else. I realize I don’t even know what part of the world we are in.

‘Where are we?’ I say.

He stands behind me. I can see us both, reflected in the glass. Me. My husband. Middle‑aged.

‘North London,’ he replies. ‘Crouch End.’

I step back. Panic begins to rise. ‘Jesus,’ I say. ‘I don’t even know where I bloody live …’

He takes my hand. ‘Don’t worry. You’ll be fine.’ I turn round to face him, to wait for him to tell me how, how I will be fine, but he does not. ‘Shall I make you your coffee?’

For a moment I resent him, but then say, ‘Yes. Yes, please.’ He fills a kettle. ‘Black, please,’ I say. ‘No sugar.’

‘I know,’ he says, smiling at me. ‘Want some toast?’

I say yes. He must know so much about me, yet still this feels like the morning after a one‑night stand: breakfast with a stranger in his house, plotting how soon it would be acceptable to make an escape, to go back home.

But that’s the difference. Apparently this is my home.

‘I think I need to sit down,’ I say.

He looks up at me. ‘Go and sit yourself down in the living room,’ he says. ‘I’ll bring this through in a minute.’

I leave the kitchen.

A few moments later Ben follows me in. He gives me a book. ‘This is a scrapbook,’ he says. ‘It might help.’ I take it from him. It is bound in plastic that is supposed to look like worn leather but does not, and has a red ribbon tied around it in an untidy bow. ‘I’ll be back in a minute,’ he says, and leaves the room.

I sit on the sofa. The scrapbook weighs heavy in my lap. To look at it feels like snooping. I remind myself that whatever is in there is about me, was given to me by my husband.

I untie the bow and open it at random. A picture of me and Ben, looking much younger.

I slam it closed. I run my hands around the binding, fan the pages. I must have to do this every day .

I can’t imagine it. I am certain there has been a terrible mistake, yet there can’t have been. The evidence is there – in the mirror upstairs, in the creases on the hands that caress the book in front of me. I am not the person I thought I was when I woke this morning.

But who was that? I think. When was I that person, who woke in a stranger’s bed and thought only of escape? I close my eyes. I feel as though I am floating. Untethered. In danger of being lost.

I need to anchor myself. I close my eyes and try to focus on something, anything, solid. I find nothing. So many years of my life, I think. Missing.

This book will tell me who I am, but I don’t want to open it. Not yet. I want to sit here for a while, with the whole past a blank. In limbo, balanced between possibility and fact. I am frightened to discover my past. What I have achieved, and what I have not.

Ben comes back in and sets a tray in front of me. Toast, two cups of coffee, a jug of milk. ‘You OK?’ he says. I nod.

He sits beside me. He has shaved, dressed in trousers and a shirt and tie. He doesn’t look like my father any more. Now he looks as though he works in a bank, or an office. Not bad, though, I think, then push the thought from my mind.

‘Is every day like this?’ I say.

He puts a piece of toast on a plate, smears butter on it. ‘Pretty much,’ he says. ‘You want some?’ I shake my head and he takes a bite. ‘You seem to be able to retain information while you’re awake,’ he says. ‘But then, when you sleep, most of it goes. Is your coffee OK?’

I tell him it’s fine, and he takes the book from my hands. ‘This is a sort of scrapbook,’ he says, opening it. ‘We had a fire a few years ago so we lost a lot of the old photos and things, but there are still a few bits and pieces in here.’ He points to the first page. ‘This is your degree certificate,’ he says. ‘And here’s a photo of you on your graduation day.’ I look at where he points; I am smiling, squinting into the sun, wearing a black gown and a felt hat with a gold tassel. Just behind me stands a man in a suit and tie, his head turned away from the camera.

‘That’s you?’ I say.

He smiles. ‘No. I didn’t graduate at the same time as you. I was still studying then. Chemistry.’

I look up at him. ‘When did we get married?’ I say.

He turns to face me, taking my hand between his. I am surprised by the roughness of his skin, used, I suppose, to the softness of youth. ‘The year after you got your Ph.D. We’d been dating for a few years by then, but you – we – we both wanted to wait until your studies were out of the way.’

That makes sense, I think, though it feels oddly practical of me. I wonder if I had been keen to marry him at all.

As if reading my mind he says, ‘We were very much in love,’ and then adds, ‘we still are.’

I can think of nothing to say. I smile. He takes a swig of his coffee before looking back at the book in his lap. He turns over some more pages.

‘You studied English,’ he says. ‘Then you had a few jobs, once you’d graduated. Just odd things. Secretarial work. Sales. I’m not sure you really knew what you wanted to do. I left with a BSc and did teacher training. It was a struggle for a few years, but then I was promoted and, well, we ended up here.’

I look around the living room. It is smart, comfortable. Blandly middle class. A framed picture of a woodland scene hangs on the wall above the fireplace, china figurines sit next to the clock on the mantelpiece. I wonder if I helped to choose the decor.

Ben goes on. ‘I teach in a secondary school nearby. I’m head of department now.’ He says it with no hint of pride.

‘And me?’ I say, though really I know the only possible answer. He squeezes my hand.

‘You had to give up work. After your accident. You don’t do anything.’ He must sense my disappointment. ‘You don’t need to. I earn a good enough wage. We get by. We’re OK.’

I close my eyes, put my hand to my forehead. This all feels too much, and I want him to shut up. I feel as if there is only so much I can process, and if he carries on adding more then eventually I will explode.

What do I do all day? I want to say but, fearing the answer, I say nothing.

He finishes his toast and takes the tray out to the kitchen. When he comes back in he is wearing an overcoat.

‘I have to leave for work,’ he says. I feel myself tense.

‘Don’t worry,’ he says. ‘You’ll be fine. I’ll ring you. I promise. Don’t forget today is no different from every other day. You’ll be fine.’

‘But–’ I begin.

‘I have to go,’ he says. ‘I’m sorry. I’ll show you some things you might need, before I leave.’

In the kitchen he shows me which things are in which cupboard, points out some leftovers in the fridge that I can have for lunch and a wipe‑clean board screwed to the wall, next to a black marker pen tied to a piece of string. ‘I sometimes leave messages here for you,’ he says. I see that he has written the word Friday on it in neat, even capitals, and beneath it the words Laundry? Walk? (Take phone!) TV? Under the word Lunch he has noted that there is some leftover salmon in the fridge and added the word Salad? Finally he has written that he should be home by six. ‘You also have a diary,’ he says. ‘In your bag. It has important phone numbers in the back of it, and our address, in case you get lost. And there’s a mobile phone–’

‘A what?’ I say.

‘A phone,’ he says. ‘It’s cordless. You can use it anywhere. Outside the house, anywhere. It’ll be in your handbag. Make sure you take it with you if you go out.’

‘I will,’ I say.

‘Right,’ he says. We go into the hall and he picks up a battered leather satchel by the door. ‘I’ll be off, then.’

‘OK,’ I say. I am not sure what else to say. I feel like a child kept out of school, left alone at home while her parents go to work. Don’t touch anything, I imagine him saying. Don’t forget to take your medicine.

He comes over to where I stand. He kisses me, on the cheek. I don’t stop him, but neither do I kiss him back. He turns towards the front door, and is about to open it when he stops.

‘Oh!’ he says, looking back at me. ‘I almost forgot!’ His voice sounds suddenly forced, the enthusiasm affected. He is trying too hard to make it seem natural; it is obvious he has been building up to what he is about to say for some time.

In the end it is not as bad as I feared. ‘We’re going away this evening,’ he says. ‘Just for the weekend. It’s our anniversary, so I thought I’d book something. Is that OK?’

I nod. ‘That sounds nice,’ I say.

He smiles, looks relieved. ‘Something to look forward to, eh? A bit of sea air? It’ll do us good.’ He turns back to the door and opens it. ‘I’ll call you later,’ he says. ‘See how you’re getting on.’

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘Do. Please.’

‘I love you, Christine,’ he says. ‘Never forget that.’

He closes the door behind him and I turn. I go back into the house.

Later, mid‑morning. I sit in an armchair. The dishes are done and neatly stacked on the drainer, the laundry is in the machine. I have been keeping myself busy.

But now I feel empty. It’s true, what Ben said. I have no memory. Nothing. There is not a thing in this house that I remember seeing before. Not a single photograph – either around the mirror or in the scrapbook in front of me – that triggers a recollection of when it was taken, not a moment with Ben that I can recall, other than those since we met this morning. My mind feels totally empty.

I close my eyes, try to focus on something. Anything. Yesterday. Last Christmas. Any Christmas. My wedding. There is nothing.

I stand up. I move through the house, from room to room. Slowly. Drifting, like a wraith, letting my hand brush against the walls, the tables, the backs of the furniture, but not really touching any of it. How did I end up like this? I think. I look at the carpets, the patterned rugs, the china figurines on the mantelpiece and ornamental plates arranged on the display racks in the dining room. I try to tell myself that this is mine. All mine. My home, my husband, my life. But these things do not belong to me. They are not part of me. In the bedroom I open the wardrobe door and see a row of clothes I don’t recognize, hanging neatly, like empty versions of a woman I have never met. A woman whose home I am wandering through, whose soap and shampoo I have used, whose dressing gown I have discarded and slippers I am wearing. She is hidden to me, a ghostly presence, aloof and untouchable. This morning I had selected my underwear guiltily, searching through the pairs of knickers, balled together with tights and stockings, as if I was afraid of being caught. I held my breath as I found knickers in silk and lace at the back of the drawer, items bought to be seen as well as worn. Rearranging the unused ones exactly as I had found them, I chose a pale‑blue pair that seemed to have a matching bra and slipped them both on, before pulling a heavy pair of tights over the top, and then trousers and a blouse.

I had sat down at the dressing table to examine my face in the mirror, approaching my reflection cautiously. I traced the lines on my forehead, the folds of skin under my eyes. I smiled and looked at my teeth, and at the wrinkles that bunched around the edge of my mouth, the crow’s feet that appeared. I noticed the blotches on my skin, a discoloration on my forehead that looked like a bruise that had not quite faded. I found some make‑up, and put a little on. A light powder, a touch of blusher. I pictured a woman – my mother, I realize now – doing the same, calling it her warpaint , and this morning, as I blotted my lipstick on a tissue and recapped the mascara, the word felt appropriate. I felt that I was going into some kind of battle, or that some battle was coming to me.

Sending me off to school. Putting on her make‑up. I tried to think of my mother doing something else. Anything. Nothing came. I saw only a void, vast gaps between tiny islands of memory, years of emptiness.

Now, in the kitchen, I open cupboards: bags of pasta, packets of a rice labelled arborio, tins of kidney beans. I don’t recognize this food. I remember eating cheese on toast, boil‑in‑the‑bag fish, corned‑beef sandwiches. I pull out a tin labelled chickpeas, a sachet of something called couscous. I don’t know what these things are, let alone how to cook them. How then do I survive, as a wife?

I look up at the wipe‑clean board that Ben had shown me before he left. It is a dirty grey colour, words have been scrawled on it and wiped out, replaced, amended, each leaving a faint residue. I wonder what I would find if I could go back and decipher the layers, if it were possible to delve into my past that way, but realize that, even if it were possible, it would be futile. I am certain that all I would find are messages and lists, groceries to buy, tasks to perform.

Is that really my life? I think. Is that all I am? I take the pen and add another note to the board. Pack bag for tonight? it says. Not much of a reminder, but my own.

I hear a noise. A tune, coming from my bag. I open it and empty its contents on to the sofa. My purse, some tissues, pens, a lipstick. A powder compact, a receipt for two coffees. A diary, just a couple of inches square and with a floral design on the front and a pencil in its spine.

I find something that I guess must be the phone that Ben described – it is small, plastic, with a keypad that makes it look like a toy. It is ringing, the screen flashing. I press what I hope is the right button.

‘Hello?’ I say. The voice that replies is not Ben’s.

‘Hi,’ it says. ‘Christine? Is that Christine Lucas?’

I don’t want to answer. My surname seems as strange as my first name had. I feel as though any solid ground I had attained has vanished again, replaced by quicksand.

‘Christine? Are you there?’

Who can it be? Who knows where I am, who I am? I realize it could be anyone. I feel panic rise in me. My finger hovers over the button that will end the call.

‘Christine? It’s me. Dr Nash. Please answer.’

The name means nothing to me, but still I say, ‘Who is this?’

The voice takes on a new tone. Relief? ‘It’s Dr Nash,’ he says. ‘Your doctor?’

Another flash of panic. ‘My doctor?’ I say. I’m not ill, I want to add, but I don’t know even this. I feel my mind begin to spin.

‘Yes,’ he says. ‘But don’t worry. We’ve just been doing some work on your memory. Nothing’s wrong.’

I notice the tense he has used. Have been . So this is someone else I have no memory of.

‘What kind of work?’ I say.

‘I’ve been trying to help you, to improve things,’ he says. ‘Trying to work out exactly what’s caused your memory problems, and whether there’s anything we can do about them.’

It makes sense, though another thought comes to me. Why had Ben not mentioned this doctor before he left this morning?

‘How?’ I say. ‘What have we been doing?’

‘We’ve been meeting over the last few weeks. A couple of times a week, give or take.’

It doesn’t seem possible. Another person I see regularly who has left no impression on me whatsoever.

But I’ve never met you before, I want to say. You could be anyone.

The same could be said of the man I woke up with this morning, and he turned out to be my husband.

‘I don’t remember,’ I say instead.

His voice softens. ‘Don’t worry. I know.’ If what he says is true then he must understand that as well as anyone. He explains that our next appointment is today.

‘Today?’ I say. I think back to what Ben told me this morning, to the list of jobs written on the board in the kitchen. ‘But my husband hasn’t mentioned anything to me.’ I realize it is the first time I have referred to the man I woke up with in this way.

There is a pause, and then Dr Nash says, ‘I’m not sure Ben knows you’re meeting me.’

I notice that he knows my husband’s name, but say, ‘That’s ridiculous! How can he not? He would have told me!’

There is a sigh. ‘You’ll have to trust me,’ he says. ‘I can explain everything, when we meet. We’re really making progress.’

When we meet. How can we do that? The thought of going out, without Ben, without him even knowing where I am or who I am with, terrifies me.

‘I’m sorry,’ I say. ‘I can’t.’

‘Christine,’ he says, ‘it’s important. If you look in your diary you’ll see what I’m saying is true. Do you have it? It should be in your bag.’

I pick up the floral book from where it had fallen on to the sofa and register the shock of seeing the year printed on the front in gold lettering. Two thousand and seven. Twenty years later than it should be.

‘Yes.’

‘Look at today’s date,’ he says. ‘November thirtieth. You should see our appointment.’

I don’t understand how it can be November – December tomorrow – but still I skim through the leaves, thin as tissue, to today’s date. There, tucked between the pages, is a piece of paper, and on it, printed in handwriting I don’t recognize, are the words November 30th – seeing Dr Nash . Beneath them are the words Don’t tell Ben . I wonder if Ben has read them, whether he looks through my things.

I decide there is no reason he would. The other days are blank. No birthdays, no nights out, no parties. Does this really describe my life?

‘OK,’ I say. He explains that he will come and pick me up, that he knows where I live and will be there in an hour.

‘But my husband–’ I say.

‘It’s OK. We’ll be back long before he gets in from work. I promise. Trust me.’

The clock on the mantelpiece chimes and I glance at it. It is old‑fashioned, a large dial in a wooden case, edged with roman numerals. It reads eleven thirty. Next to it sits a silver key for winding it, something that I suppose Ben must remember to do every evening. It looks old enough to be an antique, and I wonder how we came to own such a clock. Perhaps it has no history, or none with us at least, but is simply something we saw once, in a shop or on a market stall, and one of us liked it. Probably Ben, I think. I realize I don’t like it.

I’ll see him just this once, I think. And then, tonight, when he gets home, I will tell Ben. I can’t believe I’m keeping something like this from him. Not when I rely so utterly on him.

But there is an odd familiarity to Dr Nash’s voice. Unlike Ben, he does not seem entirely alien to me. I realize I almost find it easier to believe that I have met him before than I do my husband.

We’re making progress , he’d said. I need to know what kind of progress he means.

‘OK,’ I say. ‘Come.’

Date: 2015-04-20; view: 1176

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Where have all the criminals gone | | | The Star-Child |