CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

CHAPTER 10 BACTERIAL REPRODUCTION AND GROWTH OF MICROORGANISMS

|

FIG. 10-18Cells respond to osmotic pressure. In hypotonic solutions, cells may burst.

reach a maximum. Although light intensities above this level do not result in further increases in the rates of photosynthesis, light intensities below the optimal level result in lower rates of photosynthesis.

The wavelength of light also has a marked effect on the rates of photosynthesis. Different photosynthetic microorganisms use light of different wavelengths. For example, anaerobic photosynthetic bacteria use light of longer wavelengths than eukaryotic algae are capable of using. Many photosynthetic microorganisms have accessory pigments that enable them to use light of wavelengths other than the absorption wavelength for the primary photosynthetic pigments. The distribution of photosynthetic microorganisms in nature reflects the variations in the ability to use light of different wavelengths and the differential penetration of different colors of light into aquatic habitats.

The rate of photosynthesis is a function of light intensity and wavelength.

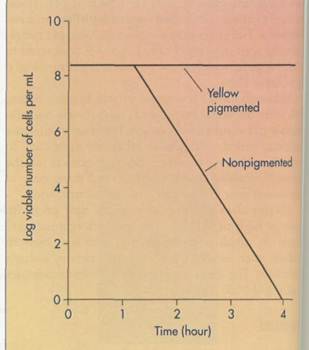

Exposure to visible light can also cause the death of bacteria (FIG. 10-19). Exposure to visible light can lead to the formation of singlet oxygen, which can result in the death of bacterial cells. Some bacteria produce pigments that protect them against the lethal effects of exposure to light. For example, yellow, orange, or red carotenoid pigments interfere with the formation and action of singlet oxygen, preventing its lethal action. Bacteria possessing carotenoid pigments can tolerate much higher levels of exposure to

sunlight than nonpigmented microorganisms. Pig-1 mented bacteria often grow on surfaces that are exposed to direct sunlight, such as on leaves of trees. Many viable bacteria found in the air produce colored pigments.

FIG. 10-19Pigmentation is important in the ability of bacteria to survive exposure to light.

SUMMARY

Bacterial Reproduction (pp. 287-288)Binary Fission (p. 287)

• Binary fission is the normal form of asexual bacterial reproduction and results in the production of two equal-size daughter cells. Replication of the bacterial chromosome is required to give each daughter cell a complete genome.

• A septum or crosswall is formed by the inward movement of the plasma membrane, separating the two complete bacterial chromosomes in an active protein-requiring process, physically cutting thechro-mosomes apart and distributing them to the two daughter cells. Cell division is synchronized with chromosome replication.

Alternate Means of Bacterial Reproduction (pp. 287-288)

• Other modes of bacterial reproduction are predomi

nantly asexual, differing in how the cellular material

is apportioned between the daughter cells and

whether the cells separate or remain together as part

of a multicellular aggregation. Budding is character

ized by an unequal division of cellular material. In

hyphae formation the cell elongates, forming rela

tively long, generally branched filaments; crosswall

formation results in individual cells containing com

plete genomes.

Bacterial Spore Formation (p. 288)

• Sporulation results in the formation of specialized re

sistant resting cells or reproductive cells called

spores. Endospores are heat-resistant nonreproduc-

tive spores that are formed within the cells of a few

bacterial genera; cysts are dormant nonreproductive

cells sometimes enclosed in a sheath. Myxobacteria

form fruiting bodies within which they produce prog

eny myxospores that can survive transport through

the air. Arthrospores are spores formed by hyphae

fragmentation that permit reproduction (increase in

cell number) of some bacteria.

Bacterial Growth (pp. 288-291)

• Binary fission leads to a doubling of a bacterial popu

lation at regular intervals. The generation or doubling

time is a measure of the growth phase.

Generation Time (pp. 288-290)

|

| Bacterial Growth Curve (pp. 291-292) • The normal growth curve for bacteria has four phases: lag, log or exponential, stationary, and death. During the lag phase, bacteria are preparing for reproduction, synthesizing DNA and enzymes for cell |

• The time required to achieve a doubling of the population size is known as the generation time or doubling time.

• The generation time is a measure of bacterial growth rate.

• The generation time of a bacterial culture can be expressed as:

division; there is no increase in cell numbers. During the log phase the logarithm of bacterial biomass increases linearly with time; this phase determines the generation or doubling time. Bacteria reach a stationary phase if they are not transferred to new medium and nutrients are not added; during this phase there is no further net increase in bacterial cell numbers and the growth rate is equal to the death rate. The death phase begins when the number of viable bacterial cells begins to decline. Batch and Continuous Growth (p. 291)

• In batch cultures, bacteria grow in a closed system to

which new materials are not added. In continuous

culture, fresh nutrients are added and end products

removed so that the exponential growth phase is

maintained.

Bacterial Growth on Solid Media (p. 291)

• On solid media, bacteria do not disperse and so nu

trients become limiting at the center of the colony;

bacterial colonies have a well-defined edge. Each

colony is a clone of identical cells derived from a sin

gle parental cell.

Enumeration of Bacteria (pp. 292-296)

Viable Count Procedures (pp. 292-294)

• Numbers of bacteria are determined by viable plate

count, direct count, and most probable number deter

minations. In viable plate counts, serial dilutions of

bacterial suspensions are plated on solid growth

medium by the pour plate or surface spread tech

nique, incubated, and counted. Since each colony

comes from a single bacterial cell, counting the colony

forming units, taking into account the dilution fac

tors, can determine the original bacterial concentra

tion.

Direct Count Procedures (pp. 294-295)

• Bacteria enumerated by direct counting procedures

do not have to be grown first in culture or stained.

Special counting chambers are often used.

Most Probable Number (MPN) Procedures (pp. 295-296)

• In most probable number enumeration procedures,

multiple serial dilutions are performed to the point of

extinction. Cloudiness or turbidity can be the crite

rion for existence of bacteria at any dilution level; gas

production or other physiological characteristics can

be used to determine the presence of specific types of

bacteria.

Factors Influencing Bacterial Growth (pp. 296-306)

• Environmental conditions influence bacterial growth

and death rates. Each bacterial species has a specific

tolerance range for specific environmental parame

ters. Changing environmental conditions cause popu

lation shifts. Laboratory conditions can be manipu

lated to achieve optimal growth rates for specific or

ganisms.

Temperature (pp. 296-301)

• There are maximum and minimum temperatures at

which microorganisms can grow; these extremes of

Date: 2015-02-28; view: 1359

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| FACTORS INFLUENCING BACTERIAL GROWTH 305 | | | CHAPTER 10 BACTERIAL REPRODUCTION AND GROWTH OF MICROORGANISMS |