CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Nasal Foreign Bodies

The example shows the construction of the Shannon code for a small alphabet. The five symbols which can be coded have the following frequency:

| Symbol | A | B | C | D | E |

| Count | |||||

| Probabilities | 0.38461538 | 0.17948718 | 0.15384615 | 0.15384615 | 0.12820513 |

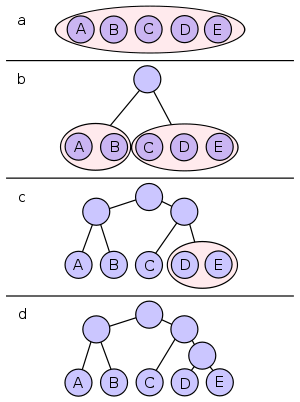

All symbols are sorted by frequency, from left to right (shown in Figure a). Putting the dividing line between symbols B and C results in a total of 22 in the left group and a total of 17 in the right group. This minimizes the difference in totals between the two groups.

With this division, A and B will each have a code that starts with a 0 bit, and the C, D, and E codes will all start with a 1, as shown in Figure b. Subsequently, the left half of the tree gets a new division between A and B, which puts A on a leaf with code 00 and B on a leaf with code 01.

After four division procedures, a tree of codes results. In the final tree, the three symbols with the highest frequencies have all been assigned 2-bit codes, and two symbols with lower counts have 3-bit codes as shown table below:

| Symbol | A | B | C | D | E |

| Code |

Results in 2 bits for A, B and C and per 3 bits for D and E an average bit number of

Shannon–Fano Algorithm

Nasal Foreign Bodies

Occasionally, foreign bodies can gain entrance into the nasal passage-ways of dogs and cats via the mouth, causing extreme irritation and rhinitis or sinusitis. The chief culprits in this category seem to be blades of grass, which is not unusual since many dogs and cats love to chew on vegetation.

Pets with nasal foreign bodies will sneeze and usually have a cloudy or bloody discharge coming from one or both nostrils. Veterinary inspection of the back of the mouth and inner entrances into the nasal passages while the pet is sedated or anesthetized is often enough to identify and extract the culprit. If not, surgery might be required to remove it and to prevent secondary complications associated with bacterial infections.

Nasopharyngeal Polyps (Cats)

Nasopharyngeal polyps are benign, pendulous masses that are associated with chronic ear infections in cats. These polyps normally arise within the throat region and extend into the latter part of the nasal cavity. They may grow to significant sizes and actually interfere with the normal flow of air into the trachea and respiratory airways, causing breathing difficulties.

Clinical signs associated with nasopharyngeal polyps in cats include noisy breathing sounds, sneezing, nasal discharge, and swallowing difficulties. If the polyps arising from the ear canal are large enough, vestibular signs including head tilting, head shaking, incoordination, and falling may also be associated with this condition.

Diagnosis of nasopharyngeal polyps can usually be definitively made on visual examination of the oral cavity of cats suspected of having this disease. Treatment involves surgical removal of the polyps.

However, such a procedure is not without its potential complications. Because of the number of nerve fibers that course through the middle ear canal, surgical removal of polyps can lead to localized nerve damage. Such damage can lead to side effects such as paralysis of the muscles of the face and excessive drooling.

Collapsed Trachea (Dogs)

Collapsed trachea is a respiratory disease primarily seen in the smaller, toy breeds of dogs, such a toy poodles and Yorkshire terriers.

It can occur in dogs of any age, but most cases are seen in dogs over 6 years of age. A weakening of the muscles that interconnect the band of cartilaginous rings that normally support the trachea causes the syndrome. The end result of this malformation is that instead of the trachea maintaining its normal round shape during respiratory activity, it collapses or flattens out. Depending on which section of the trachea is involved, this collapse might occur on either inspiration or expiration. In some cases, it might be so severe as to become life-threatening.

Obviously, such a situation leads to noticeable respiratory distress in affected individuals. In addition, dogs suffering from a collapsing trachea can have a dry, harsh cough with a characteristic “goose honk” sound to it.

Diagnosis is assisted by the type of breed involved and the type of cough heard. Radiographs taken of the trachea are usually diagnostic and will help differentiate this disorder from other diseases of the airways, including tracheitis, bronchitis, and pneumonia. Actual examination of the affected portion of the trachea with an endoscope can be used to help determine the extent and severity of the problem.

Mild cases of collapsing trachea can often be managed through medical means. If an affected dog is overweight, a weight-loss program is a good place to start. Cough suppressants and drugs designed to dilate the airways can help relieve the symptoms. Overexertion and excitement should be discouraged, since the increased respiratory rate resulting from such activities can exacerbate the condition.

Depending on the location of the collapse, surgical correction might afford a more permanent solution to the problem. This involves the implantation of special artificial support rings around the circumference of the trachea for additional support. The postoperative complications associated with such a procedure are usually minimal.

Disorders of the Teeth and Oral Cavity

Diseases and disorders affecting the teeth or oral cavity interfere with a pet’s ability to prehense and process food for digestion. In addition, other general signs associated with conditions involving these areas usually include increased salivation, swallowing difficulties, bad breath, gagging, and decreased appetite.

Malocclusion

Malocclusion occurs when the teeth lining the upper jaw fail to line up and fit properly with the teeth of the lower arcade. In the normal bite, the upper canine teeth should rest just behind the lower canines. Disruption of the normal bite pattern can be caused by trauma, improper tooth eruption, and genetics.

Brachygnathism refers to a condition in dogs in which an overbite, or overshot upper jaw, exists. Conversely, prognathism is the term referring to the undershot jaw (underbite). Both conditions are inheritable traits, passed from one generation to another. In fact, prognathism is considered normal for certain breeds, such as pugs, boxers, and bulldogs. Although not life-threatening, these anatomic maladies can interfere with normal biting action and eating, and can predispose to dental and jaw problems in affected dogs. As a result, dogs suffering from distinct overbites or underbites (unless normal for the breed) should be surgically neutered to prevent the propagation of these undesirable traits.

Malocclusion can also result from improperly positioned deciduous teeth creating abnormal eruption pathways for the permanent ones. Dental examination of the deciduous teeth performed on puppies and kittens as early as 8 weeks of age can help identify potential problems. In many instances, simply removing the offending deciduous tooth clears the path for the proper eruption of its permanent successor.

Surgical repair or reconstruction of the jaw can be used to repair trauma-induced malocclusions, which is the most common type of malocclusion seen in cats. Orthodontic correction of brachygnathism

and prognathism has been utilized in select cases, yet for ethical reasons, such procedures should be performed only for medical purposes, not for cosmetic gains.

Supernumerary Teeth

Supernumerary teeth are extra teeth within the mouth. These can be retained deciduous teeth, or can actually be permanents. Retained deciduous teeth are commonly seen in small dog breeds, including miniature poodles and Yorkshire terriers. In these dogs, the deciduous canine teeth have the greatest propensity for remaining behind. Such retained teeth can crowd the permanent ones, creating abnormal eruption pathways. In addition, because of their close proximity with their permanent counterparts, these extra teeth can serve as niduses for dental calculus buildup and infection. As long as the eruption pattern for the corresponding permanent tooth is not being interfered with, most veterinarians will postpone removal of the retained tooth (teeth) until another elective procedure, such as neutering or teeth cleaning, is performed. However, if the permanent tooth is being interfered with in any way, immediate removal is recommended.

In rare instances, duplicated permanent teeth, consisting of one or two isolated ones, or an entire arcade, can erupt. Removal of these permanent supernumerary teeth is seldom necessary unless they interfere with the normal biting action of the dog. Because of the genetic predisposition of this condition, affected dogs should not be bred.

Enamel Hypoplasia

This unfortunate condition involves the incomplete development of the hard, protective layer of enamel that normally surrounds the crown of the tooth. Enamel hypoplasia results when the enamel-producing cells within the dental arcade, called ameloblasts, are injured or destroyed prior to eruption of either the deciduous or permanent teeth. The canine distemper virus is the most notable culprit causing enamel hypoplasia to occur; other causes can include severe malnutrition and fluorine toxicity.

Teeth that lack enamel have coarse textures (due to exposed dentin) and tend to stain brown. The absence of the protective enamel coating makes these teeth especially susceptible to decay and to traumatic fractures.

For puppies and kittens suffering from enamel hypoplasia on their permanent teeth, enamel restoration procedures (such as crowning) performed by a veterinary dental specialist can add a protective layer to exposed surfaces. Ask a veterinarian for more details regarding these dentistry procedures now available for pets.

Broken Teeth

Occasionally, teeth will break or fracture as a result of trauma or disease (such as in enamel hypoplasia). If the pulp cavity of the tooth is not exposed by the break, treatment measures, aside from filing down any sharp edges, are rarely required. However, if the damage does extend down into the pulp cavity, inflammation, infection, and pain could result.

Endodontic therapy, or root canals, can be performed to salvage teeth with exposed or infected pulp cavities and dentin. The procedure involves the removal of the pulp tissue and infected dentin, thereby alleviating pain and the further progression of disease within the tooth. Cracks and fractures in the tooth can then be filled, completing the restoration procedure.

Discolored Teeth

The administration of certain antibiotics to a pregnant dog or cat can result in yellow-stained dentin within the teeth of her offspring. The same holds true for adolescents administered these drugs prior to eruption of their permanent teeth. Although this staining has no effect on the health of the teeth, it can be unsightly and detrimental in the show ring.

Calculus buildup can certainly discolor teeth so affected. If allowed to persist on a long-term basis, the tooth surface can often take on a yellow hue, even after the calculus has been removed. In these instances, the complete removal of the calculus is far more important than any discoloration left behind.

As mentioned previously, a brownish discoloration to the teeth could be the result of enamel hypoplasia. Enamel restoration procedures can be employed to deal with this problem.

Finally, a bluish-gray discoloration to a tooth is indicative of inflammation within the pulp cavity, warranting endodontic management if the tooth is to be saved.

Dental Caries (Cavities)

Because of uniquely high pH of the saliva, cavities rarely form in the teeth of dogs and cats. When they do, they are often secondary to some trauma that has disrupted the continuity of the dental enamel. Cavities in pets are managed the same way as they are in people, with dental fillings.

Periodontal Disease

Periodontal disease, or tooth and gum disease, is one of the most prevalent health disorders in dogs and cats. Studies have shown that most canines show some signs of this disease by 3 years of age. Early signs can include tender, swollen gums, and, most commonly, bad breath. More importantly, though, if left untreated, periodontal disease can lead to secondary disease conditions that can seriously threaten the health of affected pets .

It all begins with the formation of plaque on tooth surfaces. This plaque is merely a thin film of food particles and bacteria. Over time, however, plaque mineralizes and hardens to form calculus. Owners who lift up their pet’s lip and glance at its teeth, especially near the gumline, might notice brownish to yellowish buildup of calculus on the outer surface of the teeth.

Calculus tends to accumulate worse on the outer surface of the large fourth upper premolars and on the inner surfaces of the lower incisors and premolars.

This is because canine saliva is conducive to calculus formation, and the ducts from the salivary glands empty into the mouth at these particular sites. Buildup of this substance tends to be worse in smaller breeds of dogs, such as miniature poodles, Yorkshire terriers, Maltese, and schnauzers. In fact, it is not at all unusual for some of these dogs to start losing teeth by 4 to 5 years of age without at-home preventive dental care! Along with these breed predispositions, diet can play an important role in the development of periodontal disease. For instance, moist foods high in sugar content promote plaque formation much more readily than do the dry varieties. In addition, diets containing too much phosphorus (such as all-meat rations) have been linked to periodontal disease.

Certain underlying disease conditions might also promote periodontal disease as a side effect. For example, hypothyroidism can lead to gingivitis and dental complications associated with it. Periodontal disease can also occur incidentally with tumors involving the gum tissue and/or teeth.

Pets suffering from periodontal disease can exhibit a diverse selection of clinical signs. Early periodontal disease might be marked only by a decreased appetite due to swollen, painful gums. Pet owners often complain of bad breath in their pets, and might notice signs of gagging or retching as secondary tonsillitis sets in. As the disease progresses, these signs might worsen, and other symptoms, such as gum recession, gum bleeding, and tooth loss, might arise.

Infected teeth that do not fall out can form abscesses, marked by sinus infections, nasal discharges, and/or draining tracts appearing on the face. But the damage caused by periodontal disease doesn’t stop there. Bacteria can gain entrance into the bloodstream by way of the teeth and gums, seeding the body with infectious organisms. In advanced cases, these bacteria can overwhelm the host’s immune system and set up housekeeping on the valves of the heart. The resulting valvular endocarditis in turn can lead to heart murmurs and eventual heart failure.

Besides the heart, the bacteria that gain access to the body because of periodontal disease can lodge in the kidney, causing infection, inflammation, and acute damage. Over time, signs related to kidney failure might develop in affected pets.

Early cases of periodontal disease can be treated by a thorough scaling and polishing of the teeth to remove the offending calculus. This scaling needs to be professionally performed under sedation or anesthesia to ensure complete removal of the calculus under the gumline. Using special instruments to hand-scale a pet’s teeth at home without anesthesia is not only dangerous but also highly ineffective at cleaning the teeth where it counts the most, up under the gumline.

Furthermore, such scaling, if not followed by polishing, will leave etches in the enamel covering of the teeth that can serve as foci for future plaque and calculus buildup. Antibiotics will also be prescribed for dogs and cats suffering from moderate to advanced periodontal disease to combat the associated bacterial infection. Teeth that are excessively loose within their sockets serve only to propagate infection, and should be extracted. For infected teeth that are still deemed viable, a root canal can be performed as a salvage procedure. See Chapter 4 for prevention tips to help protect pets against the adverse effects of periodontal disease.

Cleft Palate

The palate is a fleshy structure located at the roof of the mouth that separates the oral cavity from the nasal passages. The firm portion located toward the front of the mouth is termed the hard palate, whereas the softer, flexible portion toward the back of the mouth is called the soft palate. Cleft palate is a disease condition in which the palate fails to fully develop, leaving a communication gap between the mouth and the nasal passages. This condition is hereditary in breeds such as English bulldogs, Boston terriers, and cocker spaniels. It can also be acquired secondary to foreign bodies puncturing the palate, or by burns caused by puppies and kittens chewing on electrical cords.

Puppies and kittens born with cleft palates often die because they are unable to suckle properly. Those that do survive initially can develop nasal infections and aspiration pneumonia if the problem is not surgically corrected in time. The recommended time of surgery for these individuals is around 6 weeks of age. Until then, daily feedings using a tube passed directly into the esophagus are indicated to prevent these secondary complications.

Esophageal Disorders

Disorders involving the esophagus will manifest themselves as difficulty in swallowing. Effortless regurgitation of solid food, which must be differentiated from vomiting and its associated abdominal spasms, often tips off the pet owner and veterinary practitioner to an existing problem with the esophagus. Because of the inability to properly swallow food, dogs and cats afflicted with esophageal disease are at high risk of accidentally aspirating food into their lungs, causing serious, life-threatening pneumonia.

Megaesophagus

Megaesophagus is a condition in which a generalized enlargement of the esophagus occurs, making it unable to push food into the stomach. Seen primarily in dogs, this condition might be inherited, or seen secondary to esophageal obstructions or neuromuscular diseases such as myasthenia gravis.

Diagnosis of megaesophagus is made by taking radiographs of the esophagus or actually visualizing the enlargement with an endoscope inserted into the esophagus via the mouth. Those dogs diagnosed with this disorder must be fed with their front end elevated on a chair or table to encourage gravity flow of food and water into the stomach.

Feeding liquid or semisolid food will also help facilitate this passage into the stomach. Depending on the cause, some individuals do improve with time. In select cases, surgery might be performed to help improve esophageal function.

Esophageal Obstructions

Obstructions can occur secondary to tumors, infections, strictures, and the ingestion of foreign objects (especially bones). As with megaesophagus, obstructions can be diagnosed using radiographs and/or endoscopy. Treatment is aimed at surgical removal of the offending agent.

Gastric Dilatation–Volvulus Complex (Dogs)

Gastric dilatation–volvulus complex (GDV), or “bloat,” is a serious, lifethreatening disorder that can strike the gastrointestinal systems of dogs, particularly those of large, deep-chested breeds. Great Danes, St. Bernards, Irish setters, standard poodles, boxers, and English sheepdogs are only a few of the many breeds that can be suddenly afflicted with GDV. Although they don’t fit the anatomical mold of these other breeds, dachshunds and Pekinese also have a higher incidence of GDV than do other similar sized breeds.

Regardless of the size and age, death can quickly ensue in these dogs if the condition is not recognized and treated with speed. Rapid ingestion of a large amount of food and water, followed by exercise, is an important predisposing cause for this disorder.

As the stomach dilates due to the large food and water content within, and due to the gas formed within the stomach secondary to vigorous exercise, it can rotate or twist in such as way as to block off all entry into and exit from the stomach. The condition snowballs as the food, water, and gas within are not allowed to escape, and more and more gas and fluid are produced by the churning action and secretions of the distressed stomach. In addition, as the stomach dilates and/or rotates, it can effectively put pressure on the large blood vessels located within the abdomen and seriously reduce blood flow through them. This, in turn, places almost every major organ within the abdomen in serious jeopardy.

Dogs suffering from an acute case of GDV will exhibit signs such as a distended, bloated abdomen, vomiting, excessive salivation, and rapid breathing. In the early stages, the dog will be quite restless because of the pain; as the disease progresses, weakness, recumbency, and shock set in.

A diagnosis of GDV is based on history and clinical signs seen. As mentioned before, treatment must be instituted in earnest to save the life of the pet. The attending veterinarian will try to pass a tube into the stomach to relieve the stomach distension; however, if the stomach is twisted, this passage might be impossible. In these cases, immediate surgical intervention is required. Intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and steroids to combat shock are among the medications used in these patients. The prognosis is guarded with any dog presented with GDV, and recurrence is not uncommon.

If a dog likes to gulp down its food as soon as it is set down, protect it from the dangers of GDV by feeding smaller portions at more frequent intervals throughout the day. In addition, discourage exercise for at least 1 hour after mealtime. For dogs that have recurring bouts with GDV, surgery can be performed as a preventive measure to “tack” the stomach down to the inner abdominal wall, thereby preventing it from twisting if bloating occurs.

Hairballs (Cats)

The accumulation of hair within the stomach is the most common cause of vomiting in cats. Because of their self-grooming habits and the roughened nature of their tongues, cats are prone to hairballs. Incidence of this problem increases during the spring and fall months

because of increased shedding. When the hair is swallowed, it can coalesce into a ball within the stomach and act as a gastric foreign body, irritating the stomach lining. Vomiting, often right after eating, and gagging are usually the result when this happens; coughing might also be noticed. Aside from these signs, those cats affected seem otherwise clinically normal.

Diagnosis of hairballs is based on clinical signs (and the absence of other clinical signs) and physical examination. If the vomiting is continuous or severe, radiographs of the stomach or direct endoscopic examination might be required to rule out other gastric foreign bodies common to cats, such as cloth, strings, and plastic wrap.

Another way to make a diagnosis of hairballs is to monitor response to treatment. There are numerous “cat laxatives” on the market that can be given to a cat suspected of harboring hairballs. These agents, most of which are merely flavored petroleum jelly, act to lubricate the hairball and facilitate its passage out of the stomach and into the stool. Once this occurs, the clinical signs seen should abate. In severe instances, surgical removal of a prominent hairball might even be required to afford a cure.

Pet owners can do their part to prevent hairballs in their cats. Giving a laxative in a preventive manner once or twice weekly should help keep things moving smoothly through the gastrointestinal tract.

One word of caution: Mineral oil should never be used as a hairball laxative, primarily because this substance can be easily aspirated into the lungs. In addition to giving hairball laxative periodically, brushing a cat’s haircoat on a daily basis will help reduce the amount of hair available for ingestion.

Intussusception

An intussusception is a life-threatening condition involving an abnormal invagination of a portion of a dog or cat’s small or large intestine into a dilated portion of bowel situated just ahead of it, causing obstruction to normal flow within the intestine. Peristalsis involving the affected gut segments further aggravates the intussusception, making it worse with time. In especially severe instances, the blood supply to the portion of the intestine involved will be cut off, resulting in the death of that tissue and serious health problems.

The site at which an intussusception is most likely to occur in dogs is where the small intestine links up with the large intestine. The causes of an intussusception can include any type of inflammation within the gut, viral infections, parasites, tumors, and swallowed foreign objects. Strings and other linear foreign bodies are often the underlying causes of intussusceptions in cats. Signs seen in pets affected include lethargy, abdominal pain, fever, and vomiting.

Radiographs are the most useful tools in the diagnosis of an intussusception, since it has its own characteristic appearance on a radiograph. If intussusception is suspected or diagnosed, immediate surgery is necessary to correct the invagination and to remove any dead portions of bowel that might be present. Obviously, the underlying problem that initially caused the intussusception must be corrected as well.

Intestinal Obstructions

In addition to intussusception, other items can obstruct normal flow through the gut and result in clinical signs, such as lethargy, vomiting, and black, tarry stools, and abnormal posture. Swallowed foreign bodies (such as bones, rubber balls, and stones), tumors, fungal infections, and herniations are all capable of causing either partial or complete obstructions if large or extensive enough. Unless the obstruction is relieved in a timely fashion, usually through surgical means, loss of blood supply to the affected portion can occur, resulting in the death of that portion of bowel, systemic infection, and shock.

Abscesses

Abscesses are usually painful to the touch and are often associated with other signs, such as fever, depression, and loss of appetite. They also tend to be fluctuant when direct pressure is applied to them. Abscesses are seen in cats more often than dogs.

Hematomas and Seromas

Hematomas and seromas result from leakage of blood or serum, respectively, from damaged blood vessels. Traumatic blows to the skin can result in hematoma or seroma formation beneath the affected area of skin. The swellings caused by these lesions are also fluctuant, and because of the traumatic nature of their occurrence, they can be painful as well.

In most cases, the swellings caused by hematomas and seromas will resolve on their own with time, assuming that infection does not occur in the meantime.

Cysts

A cyst is simply a well-defined pocket filled with fluid, secretion, or inflammatory debris. Unlike abscesses, cysts are seldom painful to the touch.

Sebaceous cysts or epidermoid cysts develop within the skin of dogs when the sebum normally formed within sebaceous glands is not allowed to escape. There does seem to be a breed predisposition for this problem, with cocker spaniels, springer spaniels, terriers, and shepherds most commonly affected.

Sebaceous cysts can arise in multiple locations over the body of these dogs, and can constantly recur throughout the life of the pet. Although they pose no specific danger to the health of a dog, extra large cysts should be surgically excised.

Date: 2014-12-28; view: 1506

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Example | | | Granulomas |