CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY

When United States automaker Henry Ford published his autobiography My Life and Work, in 1922, he used his chapter headings to frame a series of questions: How Cheaply Can Things be Made? Money— Master or Servant? Why be Poor?

These are precisely the questions that have fascinated generations of American business and industrial leaders. In their drive to find answers, business people in the United States have probed relentlessly for ways to make and distribute efficiently more products for less money and to make a greater profit. To a remarkable extent, they have succeeded. American business firms have reached astonishing levels of productivity and profit. In doing so, they have helped to provide greater affluence and a higher standard of living for a larger percentage of the population in the United States than has ever been the case in any other large society.

There have been social costs, to be sure— costs imposed by greed, by ruthlessness and by inevitable clashes of interest—and debate often surrounds the relative costs and benefits of the American way of doing business. Yet the undeniable successes of American business have stirred widespread admiration and emulation. Entrepreneurs in Karachi or in Caracas have much the same goals as entrepreneurs in Carson City, Nevada. Like Henry Ford, they ask, "Why be poor?" And like Henry Ford, they answer they- question in deeds and only incidentally in words.

THE ROOTS OF AFFLUENCE

No single factor is responsible for the successes of American business and industry. Bountiful resources, the geographical size of the country and population trends have all contributed to these successes. Religious, social and political traditions; the institutional structures of government and business; and the courage, hard work and determination of countless entrepreneurs and workers have also played a part.

The vast dimensions and ample natural resources of the United States proved from the first to be a major advantage for national economic development. With the fourth largest area and population in the world, the United States still benefits greatly from the size of its internal market. The Constitution of the United States bars all kinds of internal tariffs, so manufacturers do not have to worry about tariff barriers when shipping goods from one part of the country to another.

A population of more than 250 million people provides both workers and consumers for American businesses. Thanks to several waves of immigration, the United States gained population rapidly throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, when business and industry were expanding. Population grew fast enough to supply a steady stream of workers, but not so fast as to overwhelm the capacity of the economy.

Rapid growth helped to promote a remarkable mobility in the American population—a mobility that contributes a

useful flexibility to business life. Census figures show that, over a five-year period, about one family in 10 moves to a new state. (The United States contains 50 states in all.) Mobility has been not only geographical but also social and economic. Lacking the rigid social classes of many European nations, the early United States provided many opportunities for advancement, although mainly for those who were Caucasian. Racial barriers that long blocked advancement for darker-skinned peoples, however, have largely disappeared in the past three decades. Class structure today is quite fluid.

The American people have possessed to an unusual degree the entrepreneurial spirit that finds its outlet in such business activities as manufacturing, transporting, buying and selling. Some have traced this entrepreneurial drive to religious sources. They have said, for example, that a "Puritan ethic" or "Protestant ethic" imbues many Americans with the belief that devotion to one's work is a way of pleasing God, and that success in business can be an onward sign of God's blessing. Others have put forward a contrary view. They have argued that capitalist enterprise often is characterized by a material acquisitiveness that could develop only in the absence of deep religious feeling.

A variety of institutional factors have favored the success of American business and industry. Mindful of the potential for abuse that lay in a powerful government, the founders of America's political institutions sought to limit governmental powers while widening opportunities for individual initiative. The relative reluctance of American political leaders to intervene in economic activities gave great freedom to market forces. By channeling economic initiative into activities that promised the greatest return on investment, free-market institutions fostered dynamic growth and rapid change. One result was a rapid accumulation of capital, which could then be used to produce further growth.

THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Under British rule, the American colonies developed a thriving merchant class but relatively little industry. Like other European nations of the 17th and 18th centuries, Britain followed a policy known as mercantilism. That policy sought to build up Britain's economy by ensuring a favorable balance of trade and promoting expansion of industries within the mother country. Colonies, whether in America or elsewhere, were consigned largely to two roles—as suppliers of raw materials and as markets for British manufactured goods. British laws restricted trade between the colonies and third countries. They also barred certain types of manufacturing within the colonies.

Despite such laws, American colonists did begin a few types of manufacturing. Access to high-quality American timber helped to make shipbuilding a leading industry in coastal areas. Other early industries included the making of textiles, shoes, ironware and rum.

A few colonists prospered by entering commerce. They served as agents for British merchants or bought and sold on their own account. Some amassed fortunes that would

later serve as a source of capital for the expansion of American industry.

The United States that emerged from the American Revolution of 1776 was principally an agricultural country. It would remain so for another century, but some early decisions by American social and political leaders planted the seeds of industrial growth. For example, the first Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, persuaded Congress to establish a protective tariff—a tariff high enough to discourage imports and give domestic industries time to grow. This and other Hamiltonian measures gave great encouragement to business in general.

Early American industries depended largely on skilled artisans working in small shops to serve a local market. But the Industrial Revolution that started in England during the 18th century did not take long to cross the Atlantic. It brought many changes to American industry between 1776 and 1860. Because labor was scarce in the United States and wages were high, employers welcomed any new method that could reduce the requirement for labor.

One key development was the introduction of the factory system, which gathered many workers together in one workplace and produced goods for distribution over a wide area. The first factory in the United States is generally dated to 1793. It was a cotton textile mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, that combined carding, roving and spinning operations.

A second development was the "American system" of mass production which originated in the firearms industry about 1800. The new system required precision engineering to create parts that were interchangeable. This, in turn, allowed the final product to be assembled in stages, each worker specializing in a specific operation.

A third development was the application of new sources of power to industrial tasks. Large water wheels and water turbines drove the machinery of early factories. As the steam engine was perfected, it provided an alternative source of energy, first for mobile operations such as powering steamboats and locomotives, then for factories. The textile industry, the dominant American industry for many decades, did not complete the switch to steam power until after 1860.

New forms of business organization— notably the bank and the corporation— facilitated the growth of industry. The first American commercial banks appeared in the 1780s and more banks soon followed. For many years, the only paper money consisted of "bank notes" that represented a particular bank's promise to pay. Banking policy was highly controversial and early attempts to establish a national or central bank were shortlived. Not until 1863 did the United States create a truly national banking system with a standard paper currency.

In the early years of the United States, banks were one of the few businesses organized in the form of corporations. The creation of each corporation required a special law. As time passed, business people found the corporation to have irresistible advantages over the sole proprietorship and the partnership. Unlike those types of businesses, the corporation survived the death of its founder or founders. Because it could draw on a pool of investors, it was a much more efficient tool for raising the large amounts of capital needed by expanding businesses. And, as it finally evolved, it enjoyed limited liability, so investors risked only the amount î their investment and not their entire assets.

Many people objected to the very idea of the corporation. It had, as one critic said, "no body to be kicked and no soul to be damned." But the rise of the corporation proved unstoppable. Connecticut, in 1837, became the first state to pass a general act of incorporation, making it relatively simple for any group to get a corporate charter by complying with a set of standard rules. As late as 1860, however, most manufacturing enterprises were still organized as sole proprietorships or partnerships.

The construction of railroads beginning ii the 1830s, marked the start of a new era for th< United States. Large infusions of private capital from Europe mainly after 1850, helped to pay for the railroad lines that soon snaked across the North American continent. Local, state and national governments contributed both money and land. Private American investors contributed, too. The greatest thrust in railroad building came after 1862, when Congress set aside public land for the first transcontinental railroad.

By providing transportation links betweei far-flung parts of the United States, the railroads increased business activities and the spread of settlements. But that was not all. Railroad construction created a growing demand for coal, iron and steel, helping to support the heavy industries that expanded rapidly in the decades after the Civil War (1861-1865). One growing industry specialized in machine tools—that is, tools used in the production of other goods. An expanding agricultural equipment industry turned out a dazzling array of machines for use on American farms.

Up to the 1880s, the bulk of Americans' income came from farming. The census of 1890 was the first in which the output of American factories was shown to exceed that of American farms. Thereafter industry in the United States grew by leaps and bounds. By 1913, more than one-third of the world's industrial production came from the United States.

The rise of industry caused what amounted to an upheaval in American life. Workers had to adapt to new forms of discipline—regular hours; strict rules of behavior; various forms of supervision. Relations between employers and employees took on a more impersonal and sometimes hostile cast. As time passed, industrial enterprises grew larger, stirring widespread concern about the dangers of monopoly. In a later section of this essay, we shall see some ol the ways in which American political institutions have responded to those concerns.

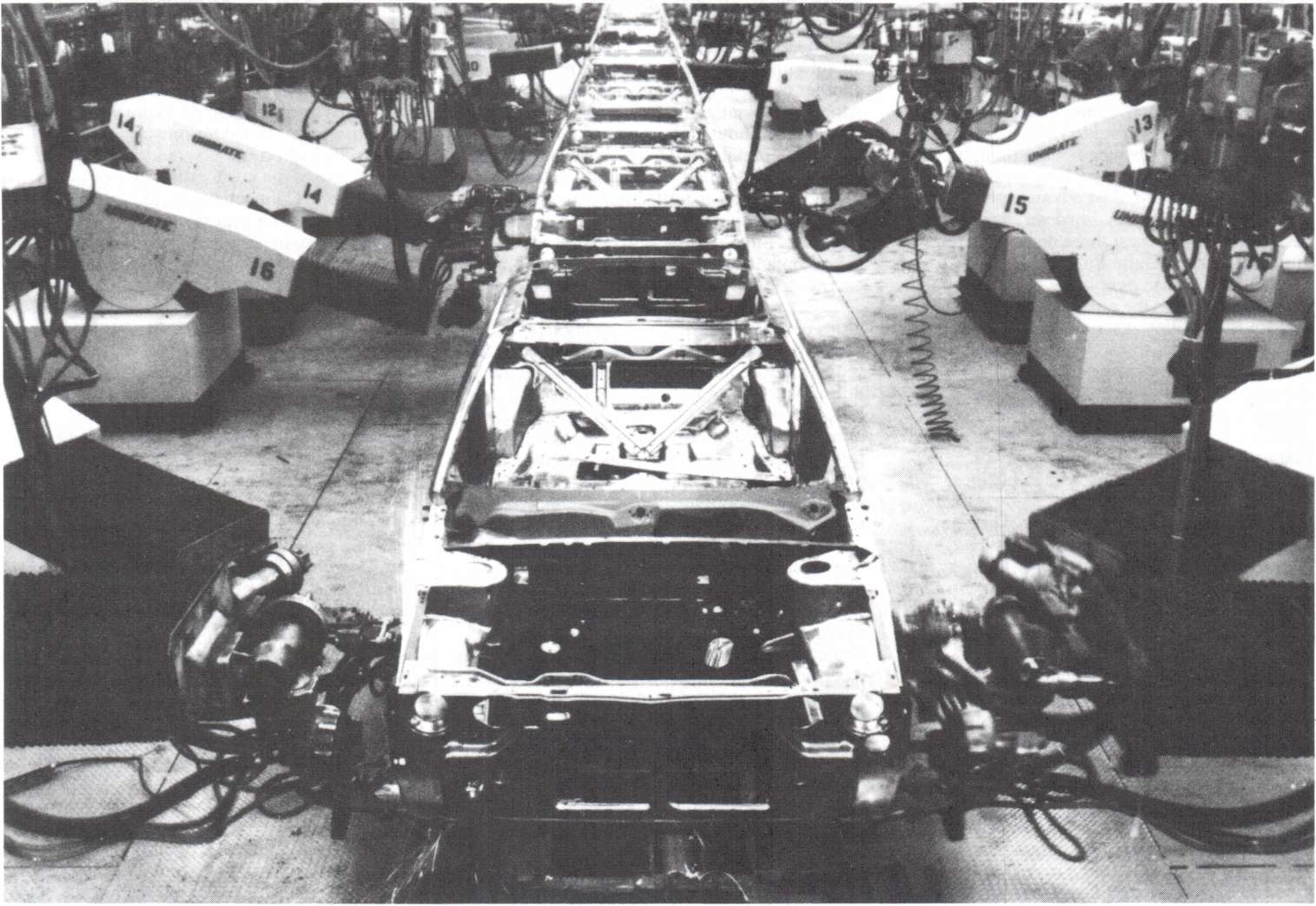

Meanwhile, the ways in which businesses in the United States organized their work were changing. In 1913, the automaker Henry Ford introduced the "moving assembly" line. This was a variation on the earlier practice of continuous assembly. By improving efficiency it made possible a major saving in labor costs. A new breed of industrial managers began the careful study of factory operations with the aim of finding the most efficient ways of organizing tasks. Their concepts of "scientific

management" helped to lower the costs of production still further.

Lower costs made possible both higher wages for workers and lower prices for consumers. More and more Americans were gaining the ability to purchase products made in the United States. During the first half of the 20th century, mass production of consumer goods such as cars, refrigerators and kitchen ranges helped to revolutionize the ways in which Americans lived.

The century's two world wars spared the United States the devastation suffered by Europe and Asia, and American industries proved capable of great production increases to meet war needs. By the time World War II ended in 1945, the United States had the greatest productive capacity of any of the world's nations.

The 20th century has seen the rise and decline of a succession of industries in the United States. The auto industry, long the centerpiece of the American economy, has had to struggle to meet the challenge of foreign competition. But over the years many new industries have appeared. Their products range from airplanes to television sets; from microchips to space satellites; from microwave ovens to ultra-high speed computers. Many of the currently rising industries are among what are known as high-technology or "high-tech" industries because of their dependence on the latest developments in technology.

High-tech industries tend to be highly automated and thus to need fewer workers than traditional industries such as steelmaking. As high-tech industries have grown and older industries have declined in recent years, the proportion of American workers employed in manufacturing has declined. Service industries—industries that sell a service rather than make a product—now dominate the economy. Service industries range from banking to telecommunications to the provision of meals in restaurants. It is sometimes said that the United States has moved into a "post-industrial era."

THEMES IN AMERICAN BUSINESS LIFE

A number of recurrent themes weave themselves through the fabric of American business life. A few are:

• What role for government? For more than two centuries, the theory of laissez-faire has dominated government policy toward American business. Laissez-faire ("leave it alone") allows private interests to have virtual free rein in operating business. The great prophet of laissez-faire was the 18th century Scottish philosopher Adam Smith, whose economic ideas had a strong influence on the development of capitalism. Smith argued that the actions of private individuals, motivated by self-interest, worked together for the greater good of society, as if individuals were guided by "an invisible hand." Smith did favor some forms of government intervention, mainly to establish the ground rules for free enterprise. But it was Smith's criticisms of mercantilism and his advocacy of laissez-faire that spurred his popularity among Americans.

Devotion to laissez-faire has not prevented private interests in the United States from turning to the government for help on numerous occasions. Railroad builders accepted grants of land and public subsidies. Industries facing strong competition from abroad have appealed for a greater degree of protectionism in trade policy. Farmers, manufacturers, labor unions, bankers and others have sought government assistance in many forms, from tax breaks to outright subsidies.

Thus, there has been a constant give-and- take between the theory of laissez-faire and concrete demands for government help for a specific economic purpose. The American public has often split into two groups, usually called conservatives and liberals, on the issue of laissez-faire. In contemporary American politics, a conservative is one who generally favors private initiative and opposes government intervention; a liberal is one who, while generally supporting private enterprise, is more willing to embrace government intervention.

• Protectionism or free trade? A second recurrent theme has been the debate over trade policy. Protectionist measures, such as those advocated by Alexander Hamilton, have often held sway. As a rule, manufacturers and industrial workers have been the strongest supporters of protectionism. The United States had generally high tariffs from the 1790s to the 1830s, from the 1860s to 1913 and from 1921 to 1934. In response to complaints that high tariffs were making the Great Depression of the 1930s worse, a period of trade liberalization began with Congress' adoption of the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934. In the 1970s and 1980s renewed economic stress has evoked calls for a return to protectionism.

• Big business or small business? Since about the time of the Civil War (1861-1865), the United States has experienced several waves of business concentration. One was from 1897 to 1904, when such giant manufacturing firms as United States Steel came into existence. Another was in the 1960s, when large corporations became even larger conglomerates by taking over companies in unrelated lines of business.

Supporters of concentration have argued that only large enterprises can benefit from the advantages of scale that accompany modern industrial methods. The larger a business grows, the lower its overhead costs per unit tend to be. If American businesses had not grown bigger, they would have been unable to compete with large foreign competitors, supporters of concentration say.

Few if any Americans believe that complete return to small-scale enterprise would be either possible or desirable. But many have criticized the ways in which concentration has occurred and the degree of economic power that some of the largest corporations have come to wield. A few have argued for a government takeover of major industries under a system of democratic socialism. Others have argued, to greater effect, for vigorous enforcement of laws designed to preserve competition. Such laws include the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 and the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, which seek to block business concentrations (or "trusts") deemed to be "in restraint of trade," and the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, which set up a government organization to guard against unfair competition.

In recent years, growing competition from foreign companies has added a new element to the debate. By one count, some 75 percent of American products currently face foreign competition within markets in the United States. Nowadays, when government antitrust enforcers consider the effects of a corporate merger, they are less likely to assume that mere bigness is going to be harmful. Instead, they are likely to judge the merger according to whether or not it promotes "economic efficiency"—that is, more efficient operation for United States-based industry.

• Relations between management and labor. Still another contentious issue has been the relative rights and responsibilities of management and labor. While management has usually held the upper hand in management-labor disputes in the United States, organized labor, promising higher wages and improved benefits, made major gains under laws adopted by Congress in the 1930s. Those laws established a legal framework for worker representation and for the collective bargaining process. However, support for unions in the United States has always been sporadic and lacking an ideological or even specifically political component. In recent years, labor unions have seemed to be losing ground. Their bargaining power declined—and management's strengthened—during the economic downturns of the 1970s and 1980s.

• The ups and downs of the business cycle. Business activity in the United States has followed a cyclical pattern of ups and downs, as is common in market economies. The period of time from the peak (high point) to the trough (low point) of a cycle varies greatly, from as little as three to as many as 15 years. Because of the cyclical nature of business activity, such economic indicators as employment rates and investment levels are constantly fluctuating. Over time, however, the level of business activity has tended to rise. For example, the total United States Gross National Product, calculated in constant dollars (that is, not counting the gain due to inflation), doubled between 1960 and 1977. It has risen at a slower rate since 1977.

INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS

There have been times when the United States followed an isolationist foreign policy, but in business matters the United States has been strongly internationalist. Ever since the 1790s, when American entrepreneurs began shipping furs to China, American firms have sought markets in other countries. The American business presence abroad has been a source both of strength and of controversy for many decades.

American diplomacy has often helped to open doors for American business abroad. That is what happened in China after 1899 when the American government adopted what became known as the "Open Door" policy. (At the time, other industrial nations were carving out spheres of influence in China and trying to shut out foreign competitors.) But the relation between business interests and diplomacy has worked both ways. American political leaders have often encouraged American businesses to invest abroad as a way of strengthening the American diplomatic hand. Early in the 20th century, for example, the policy known as

"Dollar Diplomacy" favored American investments in parts of the world that had a strategic interest for American policy-makers.

Not surprisingly, the American business presence has received a mixed welcome in the rest of the world. Many people—especially those who are critical of United States foreign policy—see American business activities as an extension of its diplomacy. Critics charge American firms with using their economic power to influence foreign governments into adopting policies that serve United States political and economic interests rather than local interests.

On the other hand, many people in other countries have welcomed investments by American firms as a means of raising their own standards of living. Foreign investments, whether by American firms or by companies from other nations, help to spread new technology and promote economic growth on a worldwide scale. By investing abroad, American businesses have provided many new jobs and new products for people who lacked access to the benefits of modern industrial society. They have opened up new avenues for advancement and new outlets for the ideas and energies of millions of people.

By injecting new capital into other countries, American investors are doing what British, French and other European investors did for the United States in the last century. They are improving the local economy and setting in motion powerful forces—economic forces that transcend the immediate goals of investors and policymakers. Once in motion, such forces take on a life of their own. Their ultimate effect is completely unpredictable.

Indeed, some Americans are concerned by the thought that, in investing abroad, American businesses are merely building up the competition that industries in the United States must face. They note that American government policies after World War II fostered the economic resurgence of Japan. American business firms helped out by sharing technology and by sending experts to Japan to teach such practices as quality control— practices that the Japanese have since carried to new, and profitable, heights.

Certainly, American industries have had to face mounting competition from producers in the rest of the world in recent years. The competitiveness of the worldwide economy can be expected to intensify in the years ahead. American business people can draw upon their long experience with the give-and-take of free- market forces to sharpen their competitiveness and help them to make a good showing. But the competition is certain to be rigorous.

BUSEVESS IN AMERICAN SOCIETY

Americans have what might be called a love- hate relationship with business. People tend to admire the drive and ingenuity of business people and the material benefits of their endeavors. However, some people harbor an image of the business person as a greedy manipulator who will stop at nothing in the never-ending pursuit of profit.

Anyone who has ever seen an episode of the American television show "Dallas" has glimpsed an extreme caricature of business' image. The show depicts manipulation and dealings in the Texas oil industry, as the

members of a wealthy Dallas family connive and scheme against one another and against other business rivals. Such extremes rarely occur in the reality of U.S. business.

On the other hand, works that cast business people as heroes have also been produced. The 19th-century author Horatio Alger wrote a series of popular books for boys that played endless variations on a "rags-to- riches" theme. Alger's heroes were young men who gained success in business by virtue of hard work and frugal living. Those same virtues are widely hailed as a path to success today. The lists of best-selling books often include works by successful business people relating their personal formulas for getting ahead.

Business organizations in the United States have been eager to spread the message of free enterprise to new generations of Americans. Through a variety of means, they carry their message into the schools and onto the television screens of the nation. One of many activities sponsored by United States businesses is a nationwide program called Junior Achievement. Local business people help high-school-age "junior achievers" to organize small companies, sell stock to friends and parents, produce and market a product (key chains, perhaps, or wall decorations) and pay stockholders a dividend. The same young people act as company officers, salespeople and production workers. The idea is to give young people a deeper appreciation to the role entrepreneurship plays in a capitalist society and to give them experience in business practices.

The values promoted by Junior Achievement are widely respected in American society. But sometimes business values come into conflict with other social values and business people feel themselves to be on the defensive.

Take the role of advertising as an example. In the eyes of the business world and of many economists, advertising serves an indispensable function. It helps consumers to choose among competing products. Also, by spurring demand for products, it extends the possibilities of mass production and thus leads to economies of scale and to lower consumer costs. Indeed, advertising is sometimes depicted as "the engine of prosperity." From another perspective, however, advertising goes against important social values. It promotes self-indulgence and thus counters moral and religious teachings that urge selflessness. It creates false "needs" and encourages waste.

This inevitable tension between business values and other social values often spills over onto the political stage, with the institutions of government struggling to resolve a point at issue. Should there be limits on the types of products that business people can advertise? Should advertisers be forced to mention the hazards as well as the attractions of a product such as cigarettes? Should advertisers be required to substantiate their glowing claims? The give-and-take of the democratic political process provides answers to such questions in a continuing process of adjustment and change—increasingly offering protection to the consumer against false or harmful advertising.

It would be difficult to overestimate the role of business and industry in underpinning the democratic political system in the United

States. By spreading economic decisionmaking among many levels of society, the American economic system has helped to avoid the concentration of political and economic power in a few hands. By providing a constantly expanding "pie" of material wealth, business and industry have helped to smooth out the inevitable conflicts over how the "pie" should be divided. Political debate has generally focused on how to fine-tune the distribution of wealth, not on drastic proposals for change. This does not mean that all Americans are satisfied with things as they are many are not. But thanks to the affluence provided by business and industry, Americans have been able to contemplate their difference: with a certain detachment, largely avoiding the desperation and extremism that are the enemies of democratic discourse.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Galbraith, John K.

The Affluent Society. 4th ed.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1984.

Mayr, Otto and Robert C. Post.

Yankee Enterprise: The Rise of the American

System of Manufactures.

Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1982.

Novak, Michael.

The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1982.

Porter, Glenn, ed.

Encyclopedia of American Economic History. New York: Scribner, 1980.

Sevareid, Eric and John Case. Enterprise: The Making of Business in America.

New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983.

Date: 2015-02-28; view: 1923

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| AMERICAN SCIENCE COMES OF AGE | | | LABOR IN AMERICA |