CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

AMERICAN SCIENCE COMES OF AGE

As in the case of transistor and computer development, Americans have an outstanding record of applied science and technology achievements. From zippers to lasers, Americans have produced more successful inventions than any other people on Earth. But until the second half of the 20th century, Americans were considered far behind Europeans in terms of "pure" science discoveries, concepts and theories.

In terms of basic science achievements, nations are usually judged by the numbers of Nobel Prizes won by their scientists in physics, chemistry and physiology/medicine. The will of Alfred Bernhard Nobel (1833-1896), a Swedish scientist, called for the prizes to be awarded each year for outstanding work in physics, chemistry, physiology/medicine, literature and the promotion of peace. (Economics was added to the list in 1969.)

The first Nobel Prizes were awarded in

1901. In that year and for several subsequent years, the winners in the three science categories were Europeans. The first American scientist to win a Nobel Prize was Albert Abraham Michelson (1852-1931). Michelson, who was born and educated in Europe, won the 1909 prize in physics for determining the speed of light.

Five years passed before another American received a Nobel Prize in science. Theodore W. Richards (1868-1928) won the 1914 chemistry prize for determining the atomic weights of many chemical elements.

It was not until 1930 that an American scientist won a Nobel Prize in physiology/medicine. In that year Karl Landsteiner (1868-1943) was awarded a prize for his discovery of human blood groups.

During the first half century of Nobel Prizes—from 1901 through 1950—Americans were in a definite minority in all three science categories. This pattern started to change in physics by the late 1930s and in the other two science categories by the late 1940s. From 1950 through 1985, more American scientists have won Nobel Prizes than the scientists of all other nations combined.

NUCLEAR ENERGY

Going into the second half of the 20th century, the strong United States lead in applied science and technology was broadened to encompass many areas of theoretical science. These include nuclear physics, genetics, space exploration and the manipulation of light.

One of the most spectacular—and controversial—achievements of United States science and technology has been the harnessing of nuclear energy. This achievement was based on scientific concepts developed since the beginning of the 20th century. The concepts were provided by scientists of many lands. But the scientific and technological effort needed to turn abstract ideas into the reality of nuclear fission was provided in the United States during the early 1940s. Nuclear fission is the generation of energy by splitting the nuclei of certain atoms.

The idea of nuclear fission can be traced back to the work of Lord Rutherford and Frederick Soddy between 1901 and 1906. The two British scientists studied the makeup of the atomic nucleus and concluded that a great store of energy was locked in each nucleus. Soddy suggested that someday that enormous energy might be released.

Fear that such an atomic war might occur swept through the international scientific community in 1938. Word leaked out that German scientists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann had split a uranium nucleus by bombarding it with subatomic particles. Other nuclear physicists soon realized the significance of this event. Albert Einstein, Enrico Fermi and Leo Szilard concluded that a nuclear chain reaction was achievable. In such a reaction, the splitting of each nucleus would release particles to split other nuclei. The result would be a tremendous release of energy.

Einstein (German/Jewish), Fermi (Italian) and Szilard (Hungarian) had fled to the United States to escape persecution in National Socialist Germany and Fascist Italy. And they feared that the Nazis would develop an atomic bomb. In August 1939 Einstein wrote to

President Franklin D. Roosevelt explaining that the element uranium might be turned into a great source of energy. He warned that "extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed."

This warning led to the Manhattan Project—the United States' effort to build an atomic bomb. Milestones in this effort included achievement of the world's first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction by Enrico Fermi at the University of Chicago in December 1942. Another milestone was the explosion of the first atomic bomb at Trinity Site, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945.

Various successes in developing peaceful uses of the atom—nuclear power, nuclear medicine and a new understanding of physics—have demonstrated man's creative use of this scientific breakthrough, which offers a message of hope to balance against our shared anxiety about the destructive potential of nuclear weapons.

CONTROLLING ENERGY

New developments in science and technology often trigger opposition. The introduction of labor-saving machines in early 19th-century England touched off the Luddite movement. The Luddites were workers who systematically smashed new weaving and knitting machines. The Luddites blamed the machines for a rise in unemployment and a lowering of wages.

Americans have generally been receptive to new technology. Some new developments and ideas, however, have triggered resentment and resistance from some Americans. The introduction of steam and later the introduction of electric lighting provoked some fear and hostility. But the opposition to these technologies was brief and never widespread.

Opposition to nuclear power has been a very different story. The first commercial atomic power plant started operation in Illinois in 1956. At that time it was widely predicted that nuclear power plants would supply nearly all of the nation's electricity by the 1980s. That did not happen. Opposition to the construction of nuclear plants has tended to increase rather than decrease. Safety and environmental considerations have kept construction costs high. As a result, nuclear power has not been able effectively to compete with other power sources in the United States. During the 1970s and 1980s, plans for several power plants were cancelled. Some plants under construction were abandoned and a few existing plants were closed. Much of the American opposition to nuclear power is based on environmental and personal safety concerns. Also Americans have several other more economical sources of energy. On top of that, Americans emotionally link nuclear power to nuclear weapons and to the great scientific effort that produced them both.

Since World War II, Americans have debated the benefits of scientific progress. On the one hand, science and technology have given Americans a high standard of living, greater longevity than ever before and exciting achievements in space exploration. On the other hand, science and technology have produced the dangers of radioactivity, toxic wastes, environmental disruptions and the threat of nuclear weapons.

Americans are responding to these concerns on a variety of fronts, including international arms control negotiations, environmental protection laws, development of long-term disposal sites in remote areas for nuclear wastes and creation of a "Superfund" program to clean up dangerous chemical waste sites that threaten health.

TOWARD THE FUTURE

Each new idea, each new development in science leads to many others. The pace of scientific and technological progress appears to speed up all the time. New inventions appear and quickly make hundreds of existing devices and procedures obsolete. An example is the laser—light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation.

Thirty years ago, the laser was an idea in the mind of Charles H. Townes as he sat on a park bench in Washington, D.C. Today, the intense, directional, coherent (not scrambled) energy of a laser beam is used to4 cut through diamonds and steel. As surgical tools, lasers are used to repair damaged eyes and cut away brain tumors. By focusing enormous energy on a very small area, lasers can trigger unusual chemical reactions. Because laser light does not spread and scatter like "ordinary" light, laser beams can carry information over tremendous distances. Laser light has been beamed from the earth to the moon and back again. Laser devices are revolutionizing image making, printing, copying and the recording and playing of music. Studies are underway to use lasers as the ultimate defense against a missile attack.

Two of the most exciting current scientific developments are the human genome project and the superconducting super collider. The human genome project, which will take at least 15 years and cost $3 billion, is an attempt to construct a genetic map of humans by analyzing the chemical composition of each of the 50,000 to 100,000 genes that make up the human body. But even while this enormous undertaking is in progress, scientists are using knowledge about human genes to treat diseases, such as cancer. Scientists hope that additional knowledge about human genes will lead to more effective treatments for many diseases.

The Superconducting Super Collider is an attempt to learn more about the building blocks that make up atoms. Scientists use machines called accelerators to speed protons or electrons (parts of atoms) close to the speed of light. When these particles collide, the scientists study their interactions. The Super Collider, which is expected to be in operation in the late 1990s, will achieve speeds 20 times higher than those possible today. Scientists hope it will allow them to learn more about the composition of the smallest particles of atoms—particles known as "quarks."

New developments can also have dangerous side effects. The development of nuclear power, pesticides and the plastics industry introduced serious hazards into the environment that must be treated. American scientists, policymakers and concerned citizens are now aware that new developments can have hidden dangers. Therefore, part of any scientific effort to develop new products includes an effort to detect, prevent or control any hazards.

Science and technology today, in the United States and throughout the world, are creating new worlds. And it is the responsibility of all people, as well as scientists, to make sure that these new worlds represent a genuine improvement in the quality of life for human beings everywhere.

MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION

The public's right to know is one of the central principles of American society. The men who wrote the Constitution of the United States resented the strict control that the American colonies' British rulers had imposed over ideas and information they did not like. Instead, these men determined, that the power of knowledge should be placed in the hands of the people.

"Knowledge will forever govern ignorance," asserted James Madison, the fourth president and an early proponent of press freedom. "And a people who mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power knowledge gives."

THE FIRST AMENDMENT

To assure a healthy and uninhibited flow of information, the framers of the new government included press freedom among the basic human rights protected in the new nation's Bill of Rights. These first 10 Amendments to the Constitution of the United States became law in 1791. The First

Amendment says, in part, that "Congress shall make no law ... abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press ...."

That protection from control by the federal government meant that anyone—rich or poor, regardless of his political or religious belief— could generally publish what he wished. The result, Madison declared, was that the power to decide what was harmful behavior "is in the people over the Government and not in the Government over the people."

Ever since, the First Amendment has served as the conscience and shield of all Americans who reported the news, who wished to make their opinions public, or who desired to influence public opinion. Over the past two centuries, however, the means of

communication—what we now call the "media"—have grown immensely more complex. In Madison's day, the media, created by printing presses, were few and simple— newspapers, pamphlets and books. Today the media also include television radio, films and cable TV. The term "the press" has expanded to refer now to any news operation in any media, not just print. These various organizations are also commonly called the "news media."

This media explosion has created an intricate and instantaneous nerve system shaping the values and culture of American society. News and entertainment are beamed from one end of the American continent to another. The result is that the United States has been tied together more tightly, and the media have helped to reduce regional differences and customs. People all over the country watch the same shows often at the same time. The media bring the American people a common and shared experience—the same news, the same entertainment, the same advertising.

Indeed, Americans are surrounded by information from the time they wake in the morning until the time they sleep at night. A typical office worker, for instance, is awakened by music from an alarm-clock radio. During breakfast, he reads the local newspaper and watches an early morning news show on TV. If he drives to work, he listens to news, music and traffic reports on his car's radio. At his office, he reads business papers and magazines to check on industry developments. Perhaps he helps plan an advertising campaign for his company's product. At home, after dinner, he watches the evening news on TV. Then he flips through the over 20 channels offered by cable TV to find his favorite show or a ballgame or a recent Hollywood movie. In bed, he reads himself to sleep with a magazine or a book.

Our typical office worker, like most Americans, takes all this for granted. Yet this dizzying array of media choices is the product of nearly 300 years of continual information revolution. Technological advances have speeded up the way information is gathered and distributed. Court cases have gradually expanded the media's legal protections. And, because the news media in the United States have been businesses which depend on advertising and sales, owners have always stressed appealing to the widest possible audiences.

HISTORY OF THE MEDIA

America's earliest media audiences were quite small. These were the colonies' upper class and community leaders—the people who could read and who could afford to buy newspapers. The first regular newspaper was the Boston News-letter, a weekly started in 1704 by the city's postmaster, John Campbell. Like most papers of the time, it published shipping information and news from England. Most Americans, out in the fields, rarely saw a newspaper. They depended on travelers or passing townsmen for this news.

When rebellious feelings against Britain began to spread in the 1700s, the first battles were fought in the pages of newspapers and pamphlets. Historians consider the birth of America's free-press tradition to have begun with the 1734 trial of John Peter Zenger. Zenger publisher of the New York Weekly

Journal, had boldly printed stories that attacked and insulted Sir William Cosby, the colony's unpopular royal governor.

Cosby ordered Zenger's arrest on a charge of seditious libel. As the King's representative, royal governors had the power to label any report they disliked—true or not—"libelous," or damaging to the government's reputation and promoting public unrest. Zenger's lawyer, Andrew Hamilton, argued that "the truth of the facts" was reason enough to print a story. The American jury agreed, ruling that Zenger had described Cosby's administration truthfully.

Perhaps one of America's greatest -political journalists was one of its first, Thomas Paine. Paine's stirring writings urging independence made him the most persuasive "media" figure of the American Revolution against Britain in 1776. His pamphlets sold thousands of copies and helped mobilize the rebellion.

By the early 1800s, the United States had entered a period of swift technological progress that would mark the real beginning of "modern media." The inventions of the steamship, the railroad and the telegraph brought communications out of the age of windpower and horses. The high-speed printing press was developed, driving down the cost of printing. Expansion of the educational system taught more Americans to read and sparked their interest in the world.

Publishers realized that a profitable future belonged to cheap newspapers with large readerships and increased advertising. In 1833 a young printer named Benjamin Day launched the New York Sun, the first American paper to sell for a penny. Until then, most papers had cost six cents. Day's paper paid special attention to lively human interest stories and crime. Following Day's lead, the press went from a small upper class readership to mass readership in just a few years.

It was a time that shaped a breed of editors who set the standard for generations of American journalists. Many of these men were hard-headed reformers who openly sided with the common man, opposed slavery and backed expansion of the frontier. They combined idealism with national pride, and their papers became the means by which great masses of new immigrants were taught the American way of life.

Competition for circulation and profits was fierce. The rivalry of two publishers dominated American journalism at the end of the century. The first was Joseph Pulitzer (1847-1911), a Hungarian immigrant whose Pulitzer prizes have become America's highest newspaper and book honors. His paper§, the St. Louis Post- Dispatch and the New York World, fought corporate greed and government corruption, introduced sports coverage and comics, and entertained the public with an endless series of promotional stunts. By 1886 the World had a circulation of 250,000, making it the most successful newspaper up; to that time.

The second publisher was William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951), who took Pulitzer's formula to new highs—and new lows—in the San Francisco Examiner and the New York Journal. Hearst's brand of outrageous sensationalism was dubbed "yellow journalism" after the paper's popular comic strip, "The Yellow Kid." Modern media critics would be horrified at Hearst's coverage of the Spanish-American War over Cuba in 1898. For months before the United States declared war, the Journal stirred public opinion to near hysteria with exaggerations and outright lies When Hearst's artist in Cuba found no horrors to illustrate, Hearst sent back the message: "Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war."

Pulitzer and Hearst symbolized an era of highly personal journalism that faded early ii this century. The pressure for large circulation created one of today's most important press standards: objective, or unbiased, reporting. Newspapers wanted to attract readers of all views, not drive them away with one-sided stories. That meant editors began to make su all sides of a story were represented. Wider access to the telephone helped shape another journalistic tradition: the race to be first with the latest news.

The swing to objective reporting was the key to the emergence of The New York Time; Most journalists consider the Times the nation's most prestigious newspaper. Under Adolph S. Ochs, who bought the paper in 18' the Times established itself as a serious alternative to sensationalist journalism. The paper stressed coverage of important national and international events—a tradition which s continues. Today the Times is used as a major reference tool by American libraries, and is standard reading for diplomats, scholars and government officials.

The New York Times is only one of many daily newspapers that have become signifies shapers of public opinion. Among the most prominent are The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the Boston Globe, and the Christian Science Monitor. The Miami Herald for instance, responded to the needs of its city’s; influx of Spanish-speaking residents by presenting extensive coverage of Latin America and printing a separate Spanish edition. Satellite technology has made possible the first genuinely nationwide newspapers— from the sober, thorough business paper, the Wall Street Journal, to the bright colors and personality orientation of USA Today.

Another recent phenomenon is the proliferation of supermarket tabloids, weekly sold chiefly at grocery store check-out lines. Although they look like newspapers, these publications carry little hard news and stress items about celebrities, human interest stories about children and pets, and diet and health tips. The leading tabloid, the National Enquire) claims a circulation of more than 4,000,000.

The total number of daily newspapers in t United States is shrinking—from 1,748 in 19 to 1,642 in 1988. In 1923, there were 503 communities with more than one daily newspaper. By 1988, only 49 cities had more than one paper. There are several reasons for this trend. The movement of people from cities to suburbs led to the demise of some city dailies and the creation of weekly suburban newspapers that emphasized local community happenings and drew revenues from local advertisers. And members of busy household: in which both husband and wife worked outside the home found they had less time to read and often stopped buying an afternoon newspaper. But the most important reason was probably the growing popularity of television While newspapers are read in 62 million of the nation's 91 million households, 98 percent of all American homes are equipped with at least one television. And a Roper Organization poll found that 65 percent of Americans use television as their primary source of news. Since newspapers cannot report tye news as quickly as radio and television, many papers have changed their emphasis, concentrating on features, personality profiles and in-depth news analysis rather than fast-breaking headline stories.

magazines

The same developments that spurred newspaper circulation—faster printing methods, lower prices, the lure of advertising money—also marked the beginning of mass appeal for American magazines. Several types of magazines emerged. The late 1800s saw the start of opinion journals still influential a century later, including the Atlantic Monthly, the Nation and Harper's.

But the largest readerships were won by magazines that catered to Americans' increasing leisure time and appetite for consumer goods, such as Cosmopolitan, the Ladies Home Journal and the Saturday Evening Post. Publishers were no longer just selling reading material; they were selling readers to advertisers. Because newspapers reached only local audiences, popular magazines attracted advertisers eager to reach a national audience for their products. By the early 1900s, magazines had become major marketing devices.

At the same time, a new breed of newspaper and magazine writer was exposing social corruption. Called "muckrakers," these writers sparked public pressure for government and business reforms. In 1902, for example, McClure's magazine ran a series of articles highly critical of the powerful Standard Oil Company by muckraking journalist Ida Tarbell.

Yet magazines did not truly develop as a powerful shaper of news and public opinion until the 1920s and 1930s, with the start of the news weeklies. The first, Time, was launched in 1923 by Henry Luce (18981967). Intended for people too busy to keep up with a daily newspaper, Time was the first magazine to organize news into separate departments such as national affairs, business and science. Newsweek, using much the same format, was started in 1933. Other prominent news weeklies are Business Week and U.S. News and World Report.

RADIO AND TELEVISION

The 1920s also saw the birth of a new mass medium, radio. By 1928, the United States had three national radio networks—two owned by NBC (the National Broadcasting Company), one by CBS (the Columbia Broadcasting System). Though mostly listened to for entertainment, radio's instant, on-the-spot reports of dramatic events drew huge audiences throughout the 1930s and World War II.

Radio also introduced government regulation into the media. Early radio stations went on and off the air and wandered across different frequencies, often blocking other stations and annoying listeners. To resolve the problem, Congress gave the government power to regulate and license broadcasters. From then on, the airwaves—both radio and TV—were considered a scarce national resource, to be operated in the public interest.

After World War II, American homes were invaded by a powerful new force: television.

The idea of seeing "live" shows in the living room was immediately attractive—and the effects are still being measured. TV was developed at a time when Americans were becoming more affluent and more mobile. Traditional family ways were weakening. Watching TV soon became a social ritual. Millions of people set up their activities and lifestyles around TV's program schedule. In fact, in the average American household, the television is watched 7 hours a day.

Television, like radio before it focused on popular entertainment to provide large audiences to advertisers. TV production rapidly became concentrated in three major networks—CBS, NBC and ABC.

A 30-second commercial on network television during prime evening viewing time costs $100,000 or more. A single half-hour show costs hundreds of thousands of dollars to produce. Viewers also have the option of watching noncommercial public television, which is funded by the federal government, as well as by donations from individuals and corporations.

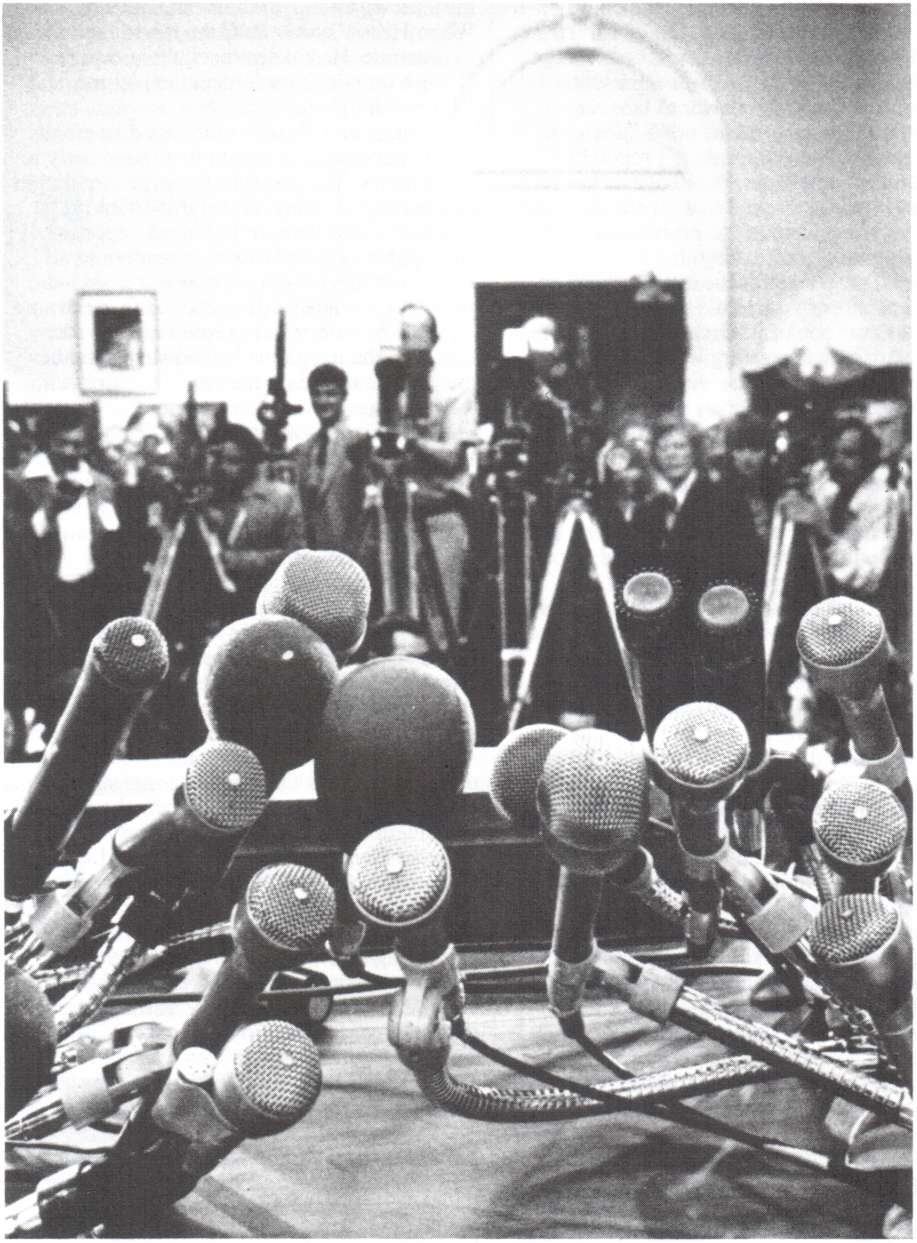

Television has emerged as the major source from which most Americans get the news. By its nature, TV has proved most effective in covering dramatic, action-filled events—such as man's walk on the moon and the Vietnam War. As TV viewers become direct witnesses of events. The focus of TV news is the network news shows watched by an estimated 60 million Americans every night. These huge audiences have made newscasters such as Walter Cronkite, Dan Rather, John Chancellor, Barbara Walters and Peter Jennings into national celebrities, far better known than print journalists.

At first it was thought that the popularity of TV and its advertiser support would cause declining interest in the other media. Instead, TV whetted the public's appetite for information. Book publishers found that TV stimulated reading. Though some big-city newspapers closed others merged and new ones opened in the suburbs. And while a few mass circulation magazines failed, hundreds of specialized magazines sprang up in their place.

Technology continues to change the media. Computers are already revolutionizing the printing process. Computer users also have access to on-line newspapers for up-to-the- minute information on general or specialized subjects. Cables and satellites are expanding TV. Already half of American homes subscribe to cable TV, which broadcasts dozens of channels providing information and entertainment of every kind.

In addition to the 1,140 television stations offering programming in 1990, there were 9,900 cable operating systems serving 44 million subscribers in 27,000 communities. These subscribers paid an average fee of $15 per month to watch programs not offered on commercial channels. One cable network offers news 24 hours a day. Some communities have publicly controlled cable television stations, allowing citizen groups to put on programs.

Still, the long awaited dream of a home completely "wired" with computer and cable TV links is a long way off. Cable TV, for instance, has not provided significantly better programming, only more of the same. The reason, critics say, is economics—the relentless pressure of seeking large audiences in order to attract advertisers.

This pressure for profits has caused concern over one of the most important trends in the

media today: The ownership of the news media, experts say, is being concentrated in fewer and fewer hands. Chains—companies that own two or more newspapers, broadcast stations or other media outlets—are growing larger. They are forcing out independent, often family-owned news media. That means that most American communities are served by news media owned by outsiders.

PUBLIC CONCERNS

Despite enjoying a period of unsurpassed wealth and influence in the 1970s and 1980s, the American media is troubled by rising public dissatisfaction. Critics complain that journalists are unfair, irresponsible or just plain arrogant. They complain that Journalists are always emphasizing the negative, the sensational, and the abnormal rather than the normal. President Reagan's science adviser expressed the irritation of many when he accused the press of "trying to tear down America."

Some observers link the criticism to rising standards in journalism. "The press is more professional, more responsible, more careful, more ethical than it ever has been," said David Shaw, media critic for the Los Angeles Times. "But we are also being far more critical toward other institutions, and people are asking, 'Why don't you criticize yourselves?'" In fact, the rise of ombudsmen (spokesmen for groups with a grievance), "opinion-editorial" pages in newspapers, television time for statements of opinion and media review journals suggest that ways are being found for individuals and groups to present their views. During the early 1980s, a number of organized groups from both sides of the political spectrum were formed to monitor and critique the news media. Political balance in news reporting became an issue of debate and controversy.

Surveys show that the American public—on both sides of the political fence— holds strong opinions about the press. According to a 1984 Gallup poll (survey of public opinion), 46 percent of Americans believe the news media's bias is liberal, while 38 percent said it is conservative. In contrast, most journalists—59 percent— described their political views as "middle of the road."

Reporters are sometimes seen as heroes who expose wrongdoing on the part of the government or big business. In the early 1970s, for example, two young reporters for the Washington Post, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, investigated a break-in at the headquarters of the Democratic Party in a Washington building known as "the Watergate." Their reporting, along with an investigation by a Congressional committee and a court trial, helped implicate high White House officials in the break-in. Woodward and Bernstein became popular heroes, especially after a film was made about them, and helped restore some glamor to the profession of journalism. Enrollments in journalism schools soared, with most students aspiring to be investigative reporters.

But there is a feeling that the press sometimes goes too far, crossing the fine line between the public's right to know, on the one hand, and the right of individuals to privacy and the right of the government to protect the national security.

In many cases, the courts decide when the

press has overstepped the bounds of its rights. Sometimes the courts decide in favor of the press. For example, in 1971 the government tried to stop the New York Times from publishing a secret study of the Vietnam War known as the Pentagon Papers, claiming that publication would damage national security. But the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that since the government had not proved that the damaged to national security would be so great, the newspapers should be free to publish the information.

One growing pressure on reporters and editors is the risk of being sued. Even though the First Amendment protects the press from government interference, the press does not have complete freedom. There are laws against libel and invasion of privacy, as well as limits on what reporters may do in order to get a story.

Libel is any false and malicious writing or picture that exposes a person to public ridicule or injures his reputation. If a broadcast or published story falsely implies that a private citizen committed a crime or is mentally incompetent, for example, the victim would probably win a libel suit. But Supreme Court decisions have made it much harder for public officials or well-known public figures to prove libel. Such persons must prove not only that the story is wrong, but that the journalist published his story with "actual malice."

The right of privacy is meant to protect individual Americans' peace of mind and security. Journalists cannot barge into people's homes or offices to seek out news and expose their private lives to the public. Even when the facts are true, most news organizations have their own rules and guidelines on such matters. For example, most newspapers do not publish the names of rape victims or of minors accused of crimes.

Americans' right to a fair trial, guaranteed by the Constitution, has provoked many a media battle. Judges have often ordered journalists—many times unsuccessfully—not to publish damaging information about a person on trial. Also, in most states journalists may be jailed for contempt of court for refusing to identify the sources for their story if demanded by a court.

TV newspeople operate under an additional restriction called the Fairness Doctrine. Under this rule, when a station presents one viewpoint on a controversial Issue, the public interest requires the station to give opposing viewpoints a chance to broadcast a reply.

In recent years, more news organizations are settling cases out of court to avoid costly— and embarrassing—legal battles. Editors say that major libel suits which generally ask for millions of dollars in damages, are having a "chilling effect" on investigative reporting. This means that for fear of being involved in a costly libel suit, the reporter or news organization may avoid pursuing a controversial story although revelation of that information might be beneficial to the public. Most affected are small news operations which do not have large profits to finance their defense. Press critics, however, say the chill factor also works the other way—against people who feel they have been wronged by publication of false information about them, but cannot afford to sue.

In short, the United States confronts a classic conflict between two deeply held beliefs: the right to know and the right to privacy and fair treatment. It is not a conflict

that can be resolved with a single formula, but only on a case-by-case basis.

A study released in 1985 by an impartial panel of prominent representatives, journalists and media observers found reasons for optimism. "The press is responding to the invisible hand of public pressure " said the panel, sponsored by the National Chamber of Commerce. "The journalist who has not struggled with...questions of ethics...is increasingly rare today."

Suggestions for Further Reading

Dizard, Wilson P.

The Coming Information Age. 2nd ed. New York: Longman, 1984.

Emery, Edwin.

The Press of America: An Interpretive History of the Mass Media. 5th ed. Englewood Cliffs, N.I.: Prentice-Hall, 1984.

Goodwin, H. Eugene.

Groping for Ethics in Journalism.

Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press, 1983.

Graber, Doris A., ed. Media Power in Politics. Washington: Congressional Quarterly, 1984.

Lieberman, Jethro K.

Free Speech, Free Press, and the Law.

New York: Lothrop, 1980.

AMERICAN ECONOMY AND FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS

AMERICAN ECONOMY AND FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS

LAISSEZ-FAIRE

In the mid-1770s, conflict spread in a group of 13 British colonies located along the eastern coast of what is now the United States of America. Over several years, the colonists had become increasingly dissatisfied with Great Britain's rule over the colonies. The colonists were being taxed without having the right to affect the way in which they were governed. Britain dictated the economic development of the colonies, forcing them to serve as a source of raw material for the "mother country" and a market for its manufactured products.

Open warfare broke out in April 1775, and a Declaration of Independence was adopted by the colonists on July 4,1776. British troops were sent to the colonies to put down the revolt. Most of the colonists believed that if Britain defeated them, they would lose the personal freedom they had found in the New World. Individual freedom—political, religious and economic—was so prized by these British citizens who had become American colonists that they were willing to fight a war (1775- 1783) in order to establish an independent nation based upon it.

The Declaration of Independence—written at the beginning of the American Revolution in 1776—and the Constitution—adopted in 1787—reveal the attitudes of late 18th century Americans about government and liberty. They believed everyone should be guaranteed certain Oughts that a government cannot take away. They also believed that the best government is the least government, a phrase which incorporates the ideas of Thomas Jefferson, primary author of the Declaration of Independence. Most Americans of that time also believed that people should be able to engage in trade, produce goods, and sell products and services without any governmental interference. This attitude toward economic activity was an important part of their general belief about the role of government.

Before the American Revolution occurred, a group of French thinkers called physiocrats (economists who regarded land as the basis of wealth and taxation) criticized the strong governmental control over trade and other economic activities common in European nations. They argued that merchants should be able to engage in trade without governmental control. Economic freedom was necessary, they argued, to increase a nation's wealth, and government policy in regard to economic activity should be one of "laissez-faire"— allowing individuals (in this case, businesses) to act as they wished.

The ideas of laissez-faire applied to economics appealed greatly to Scottish economist Adam Smith. Using these ideas, Smith began another kind of revolution during the period in which the American colonists were fighting their revolutionary war.

THE WEALTH OF NATIONS

In 1776, the year that Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence, Smith published one of the most important books in the history of economics. The book's full title is An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of Wealth of Nations. Most people simply call it The Wealth of Nations. Smith wrote the book after discussing laissez-faire beliefs with some of the physiocrats. Smith's book is an argument in favor of allowing people to engage in trade, manufacturing or other economic activity without unnecessary control or interference from government.

The main argument in The Wealth of Nations might be stated rather simply: People are naturally selfish. When they engage in manufacturing or trade, they do so in order to gain wealth and/or power. This process should not be interfered with because, despite the self- interest of these individuals, their activity is good for all of society. The more goods they make or trade, the more goods people will have. The more people who manufacture and trade, the greater the competition. Competition among manufacturers and merchants helps all people by providing even more goods and probably lower prices. This activity creates jobs and spreads wealth.

Smith concluded that individuals should own private property and be allowed to engage in private economic activity. This would result in greater wealth for all.

Smith accepted the idea that there were some things the government should do. A government is best suited to build canals or roads. A government may find it necessary to put some restrictions on international trade. And, he said, the government must not allow individual businesses to act together to control the production or trade of certain goods, thus creating a monopoly. A monopoly, in Smith's opinion, could be as harmful to the general welfare as governmental control.

Smith's book sets forth the beliefs on which the capitalist economic system is based, although he did not use the word capitalism. His ideas were warmly received by the rising merchant class throughout Europe. The book gave national governments a clear reason to let people engage freely in economic activity.

Smith's economic ideas fit perfectly with American ideas of a new type of government based on such individual rights as those to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." For citizens of the young United States, freedom from economic control seemed to go hand-in-hand with freedom from control of religion, speech and the press. Those who read Smith's book liked the idea that "natural liberty" would result if people were allowed to manufacture goods and to buy and sell them without governmental control. This would happen, Smith wrote, because people, though acting from the selfish desire to enrich themselves, would be led by "an invisible hand" (rationality) to enrich and improve all of society.

INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

The birth of the United States and the publication of Smith's book came at a time when yet another kind of revolution was taking place, the Industrial Revolution. In England, especially, machinery run by water power and later by steam power was used to manufacture cloth. This changed the ways that people worked. Instead of weaving cloth at home, people worked in factories where the machinery made much more cloth in a short time.

Americans lost no time in industrializing their new nation and in building trade with other countries.

In the 1790s, an Englishman named Samuel Slater came to America to build a cotton cloth factory. He built the machinery from memory, because it was a crime to carry factory plans out of England. The success of Slater's factory started a process of change that turned the northeastern region of the United States into an important manufacturing center. The making of textiles also meant increased demand for cotton, grown in the southern region of the United States. As a result, the nation became a major cotton producer.

Just as Slater's new factory system was being introduced, an American named Eli Whitney made cotton production more efficient by inventing a machine—the cotton gin—that rapidly removed the seeds from the bolls of cotton. Removing the seeds by hand was a difficult task; Whitney's machine made the job almost easy.

Whitney also began manufacturing rifles in a new way. Guns had always been made by gunmakers working in their homes or small shops. Because the guns were handmade individually, a part from one gun would not necessarily fit another gun. Whitney began making guns with machinery, so that all the parts were the same in each gun. This method of manufacturing goods in a factory, with interchangeable parts, helped to advance American industry.

The inventiveness of people like Slater and Whitney set the United States on a course of great economic activity. Its merchants and shipowners were conducting trade with people around the world. Its farmers were producing more food for a growing population. More people were working in factories, and an increasing number of stores and shops opened in the cities.

This economic activity increased as a result of new inventions. Some of the inventions were original American ideas; others were adapted from inventions created elsewhere. The 19th century saw the introduction of new farm machinery, sewing machines, the telegraph, railroads, food- processing plants, the telephone, the perfection of the electric light bulb, the phonograph, the camera, moving pictures and many other devices. The 20th century brought still more, among them the airplane, the use of aluminum, mass production of automobiles, radio, television, various electric household products and computers.

FREE ENTERPRISE

Most Americans think that the rise of their nation as a leading producer of manufactured goods, food and services could not have occurred under any economic system except capitalism. They believe that the economic freedom of capitalism—which many prefer to call free enterprise—is what made the United States a major economic power. Though they are not blind to the problems of capitalism, they would argue that the American economic system has created—or has the potential to create—a better life for nearly everyone in the country.

The story of American economic growth is a story of people inventing new devices and processes starting new businesses and launching new ventures. For each of these endeavors, money was needed. That money is known as capital.

Samuel Slater could not have opened that very important original textile factory unless people had been prepared to provide money to buy the land and build the factory. Slater and those capitalists would not have acted if they had not thought they would profit from their investments. Because they wanted a profit for themselves and a chance to establish even more factories later, they started a whole new American industry. This industry helped cotton growers by increasing the market for cotton. It also put more American ships to work in international trade.

The story of major companies in the United States is not much different from that of Samuel Slater's mill. Individuals started enterprises with money borrowed from others. They shared the profit gained with those investors. When they wanted to expand their businesses, they again borrowed money.

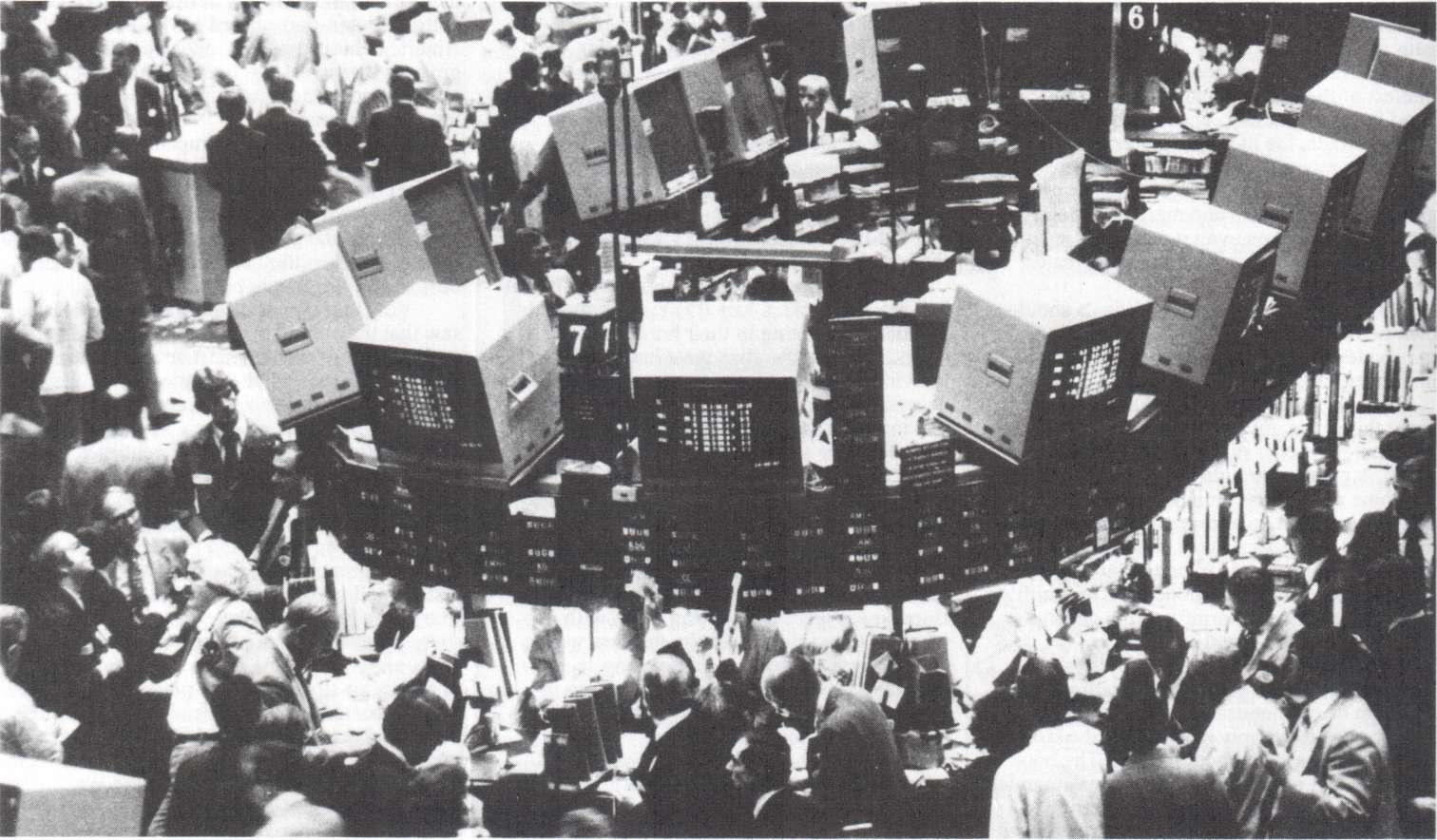

Very early, people in the United States saw that they could make money by lending it to those who wanted to start or to expand a business. That led to the creation of an important part of the current economic scene: the selling of stock, or shares, in a business. This practice started in Europe centuries before the American Revolution, but the stock trading practice was greatly increased in the vigorous free-market climate of the young United States.

In order to invest, individuals do not have to have a great deal of money: They can buy just a small portion of a business—called a share. The business of buying and selling shares in enterprises has become so big that offices have had to be set up where the selling of shares, or stock, can take place. These places, located in many cities in the United States and around the world, are called stock exchanges. The best-known is perhaps the New York Stock Exchange, located in the Wall Street area of New York City, the nation's largest city and a major business center.

Except for weekends and holidays, the stock exchanges are busy every day as people buy and sell stock. In general, individual stocks are rather low-priced, and many working Americans buy them in order to make a profit.

When people buy stock, they become part owner of the company. If the company makes a profit, they receive a share of It. Likewise, if the company loses money, the stockholders will not make a profit or the value of their shares will drop. If that happens, they lose money. For that reason, buying stock is a risk. Knowing about business is important if one wishes to make a profit in the stock market.

Not all businesses sell stock. Smaller ones usually do not. Their profits are shared by those who put their money into the business when it was started. A person who wants to start a small business—a shop, for example—may still need to borrow money. The money can come from friends or relatives or it can be borrowed from a bank—if the bank is willing to take a risk on that business.

Adam Smith would easily recognize these elements of American business, but other aspects he would not. Many problems accompanied the development of modern American industrial capitalism during the past century. Immigration and the rapid growth of American cities resulted in a large urban population seeking to earn a living. Factory owners often exploited this situation by offering low wages for long working hours, by providing unsafe and unhealthy working conditions and by hiring the children of poor families. There was discrimination in hiring: Black Americans and members of some immigrant groups were refused work or were forced to work under even more unfavorable conditions than the average worker. Entrepreneurs also took full advantage of the lack of government oversight, under the doctrine of laissez-faire, to enrich themselves by forming monopolies, eliminating competition, setting high prices for goods and producing poor quality merchandise.

REFORM

Today, the American economic system is far different from that of the 19th century. Earlier government leaders refused to do anything to control business. Except for granting financial support to companies building the railroad system in the late 19th century, the government took little role in business affairs. American citizens, however, demanded action. Workers banded together to organize unions to protect themselves. Working together, they could possibly force a company to change unfair policies. Many other Americans wrote and spoke out about unjust practices. This nationwide movement for reform, which gained strength near the end of the 19th century, was known as the Progressive Movement.

Gradually, the government began to take action. In 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, a law aimed at breaking up monopolies. It was a weak law, which later had to be strengthened by others, but it was a beginning. In 1906, laws were passed to make sure that food and drugs were correctly labeled and that meat was inspected before being sold. In 1913, the government established a new federal banking system, called the Federal Reserve System, to regulate the nation's money supply and to place some controls on banking activities.

The biggest changes came in the 1930s with the "New Deal" programs of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. During that decade the nation endured the worst business crisis and the highest rate of unemployment in its history. To ease the hardship caused by the Depression, President Roosevelt and the Congress passed many new laws regulating sales of stock, recognizing the right of workers to form unions, and setting rules for wages and hours for various workers. Stricter controls were put on the manufacturing and sale of food, drugs and cosmetics.

These laws and regulations, and many other social initiatives approved since the 1930s, have changed American capitalism from a "freely running horse to one that is bridled and saddled," as one writer described it. There is nothing a person can buy in the United States today which is not affected by government regulations of some kind. Food manufacturers must tell what exactly is in a can, box or jar. Non-packaged food is almost all inspected by government officials at some point. No drug can be sold until it is thoroughly tested and then approved by a federal agency. Many types of businesses must pass health and safety inspections by government workers, and automobiles must be built according to certain safety standards. Prices for goods must be clearly marked, and advertising must be honest. These are just a few of the many ways in which the government now protects the health, safety and money of the consumers. Laws also prohibit discrimination in hiring, forbid the hiring of young children, set standards for working conditions, and protect the rights of independent labor unions to organize, bargain and strike peacefully.

People in business believe that there is too much government regulation. They say that some of the rules they must follow are unnecessary and costly. Filling out forms to satisfy government rules costs money, and adds to the prices they must charge. On the other hand, other Americans believe that, without some regulations, at least some businesses would cheat or harm workers and consumers in order to increase business profits.

INCOME, CREDIT AND BANKING

The United States has been described as an affluent society, and despite some poor Americans, it is an accurate generalization. The median income for American families in 1990—the point that half are above and half below—was about $29,943. At retirement, most workers receive Social Security payments plus other private pension payments and personal savings. Nevertheless, roughly 13 percent of the population lives below the poverty line as established by the federal government, which in 1990 was cash income of less than $10,419 for a family of three. The number below the poverty line is lower (11 percent) when non-cash benefits such as home ownership assets and government welfare payments like food stamps are included in family income figures.

Since World War II, Americans have increasingly bought goods and services on credit. Major purchases, such as homes, cars and appliances, are paid off in monthly installments. Many Americans also possess credit cards, which allow them to buy everything from clothing to plane trips on credit, and then pay off over time from a single bill submitted by the credit card company, usually a bank. Generally the time allowed to pay is one month. Thereafter, interest is charged.

The United States has about 14,000 banks, of which 6,000 belong to the system operated by the Federal Reserve Board. Through its member banks, the Federal Reserve issues money, acts as a financial clearinghouse and establishes required cash reserves that banks must maintain. By increasing and decreasing these reserve requirements, and by changing the interest rate for loans to banks from the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks, the Federal Reserve Board can regulate the money supply and thereby attempt to control the rate of inflation in the economy.

Individual savings are usually deposited in interest-bearing accounts in several types of institutions—banks, savings and loan associations and credit unions that are usually established by employee groups. Americans also have the option of placing part of their money in savings bonds and treasury bills issued by the federal government, or in privately operated mutual funds that invest the money in the stock market.

Almost all private banks and savings institutions have insurance offered by the federal government to protect individual savings accounts up to $100,000. In the 1980s, there were major problems in the "thrift" or savings and loan (S&L) industry. These institutions, which look and act a lot like banks, make loans for the construction of homes or other buildings, and are financed by deposits from individuals and businesses. In the 1960s, when interest rates began to rise, thrifts made very risky loans. Many borrowers could not repay these loans. By the early 1980s many savings and loan institutions were insolvent, but as deposits were insured by the federal government, the institutions did not close immediately. In 1988 the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation began closing insolvent institutions. The total cost to the government to clean up the S&L problem has been estimated at more than $150 billion.

NATURE OF BUSINESS TODAY

Not all people who start businesses dream of huge multimillion-dollar corporations with international sales. Many just want to sell things—fruits and vegetables, home appliances, clothes or computers so that they can be "their own bosses." These small businesses are an important part of the economy. Many of them provide needed goods and services in city neighborhoods, in small towns or in rural areas, where large companies might not provide adequate service.

Every year hundreds of thousands of Americans start their own businesses. A government agency, the Small Business Administration, helps with information, advice, and, sometimes, loans and grants. Many large companies with many stores started as one- store operations. That is the kind of success that can be found throughout American history.

The Coca-Cola company, which distributes its soft drinks around the world, began when a pharmacist mixed together the first Coca-Cola drink and began selling it in the southern city of Atlanta, Georgia.

One of the best-known food companies in the United States is the H.J. Heinz Co., which specializes in pickles, mustard and ketchup. It had its beginnings when a teenager started to sell various food items door to door and on the street.

Before a young American named George Eastman came along in the 1880s, cameras were very difficult to use and only a trained expert could operate one well. Photographs were made on glass plates and the equipment was hard to transport. Eastman invented a new kind of film that was flexible and could be placed on a spool. He also built a camera to use his film. Starting out in a small office, he founded the now huge Eastman Kodak Company and paved the way for the many other camera companies that exist today.

Blue jeans, the popular denim trousers known to teenagers around the world, were invented by a poor cloth peddler who sold his first pairs to gold miners in California in the 1850s. His company, Levi Strauss, remains one of the largest clothing manufacturers in the United States.

The many laws and regulations of modern

American capitalism have not prevented people with ideas and dreams from starting new businesses. One example from the 1970s is that of two young men who thought they could build a new and better computer. They worked for months building the new machine, and then began gathering money to pay for its production on a large scale. One of them sold his car to get the needed capital. In 1977, they started a company called Apple Computer Corporation. By 1991, that corporation was one of the larger computer manufacturers in the United States, with annual sales of $5.5 billion.

Stories like this create an image of America as a place in which a person can go "from rags to riches," and many people have. There have been others who failed, however, and many others who have not wanted to take a chance at becoming a business owner.

One of the most significant changes in recent decades has been a shift away from the production of goods to the delivery of services as the dominant feature of the American economy. Where once most workers in the United States produced actual goods—from toothpaste to tires—most Americans today work in the sector of the economy that is broadly defined as providing services. Service industries include retail businesses, hotels and restaurants, communications and education, entertainment and recreation, federal and local government, office administration, banking and finance, and many other types of work. At the same time, as many traditional manufacturing enterprises in the United States decline or grow slowly, new companies spring up that are developing high technology computer, aerospace or biochemical products and services.

BUSINESS ÀND THE PUBLIC

Although there is much regulation of business and industry in the United States, many Americans still have a negative attitude toward what they call "Big Business." They fear its money and its influence. Some businesses employ representatives (lobbyists) in the nation's capital to try to persuade members of Congress to pass laws that make business operations less difficult. This activity is called "lobbying," and is also practiced by labor unions, farmers and many other groups. Any such interest group in America has a right to try to influence Congress, including business. In fact, consumer and environmental groups, many formed in the 1960s, are among the most vocal and effective interest groups who lobby Congress and try to mobilize public opinion through the news media.

It is also true that business groups can help create effective legislation. In the early 1980s, for example, working with Congress, drug manufacturers helped shape new laws which have led to new types of drugs being manufactured to assist in the treatment of rare diseases—with the help of government money.

On the private scene, many large businesses contribute to the promotion of culture and education. Some sponsor ballet, opera or cultural television programs. Others provide scholarship programs to help young people attend college, or help pay for certain types of sports events, concerts or other community services.

Although the American economy is not perfect, it does do what Adam Smith expected of marketplace competition. The American people in general have great purchasing power and a wide choice of available services and consumer goods—ranging from cars and boats down to low-priced candy and toys for children. Dozens of brands of soap, canned food, radios, television sets and other items can be found in the stores. Some of them are American-made, others are imported from foreign manufacturers.

The competition in the marketplace gives Americans the opportunity to compare quality and prices and to decide what they really want to buy.

As a result of the creativity, initiative and hard work which free enterprise has encouraged, the United States has become one of the most affluent nations in the world. Business freedom, combined with controls enacted for the protection of both workers and consumers, has made life in the United States more secure and comfortable for more people than has ever before been the case.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Friedman, Milton and Rose Friedman. Free to Choose: A Personal Statement. New York: Avon, 1980.

New York Stock Exchange.

Marketplace : A Brief History of the New York

Stock Exchange.

New York: New York Stock Exchange, 1982. Porter, Glenn, ed.

Encyclopedia of American Economic History. New York: Scribner,1980.

Regulation: Process and Politics. Washington: Congressional Quarterly, 1982.

Samuelson, Paul A. and William D. Nordhaus. Economics. 12th ed.

New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985.

Date: 2015-02-28; view: 3136

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY: AN AMERICAN RECORD | | | BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY |