CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

PROSPERITY AND CIVIL RIGHTS 2 page

The mix of American people today reflects this old system. For example, until the 1970s, almost 81 percent of all

newcomers to the United States emigrated from 10 nations: 14.8 percent came from Germany; 11.1 percent came from Italy; 10.3 percent came from Great Britain; 10 percent came from Ireland; 9.2 percent came from Austria and Hungary; 8.6 percent came from Canada; 7.1 percent came from Russia; 4.1 percent came from Mexico; 3 percent came from the West Indies; and 2.7 percent came from Sweden.

Immigration was slow during the "Great Depression" years of the 1930s. This was a time when one out of four Americans was without a job. In fact, more people moved out of the United States during these years than entered.

Earlier, laws had been passed specifically to exclude Asian immigrants. Citizens in the American West were afraid that the Chinese and other Asians would take away jobs building railroads, and there was much animosity toward them. In 1882, the United States banned most Chinese immigration. Other Asians were refused entry as well. By 1924, no Asian immigrants were permitted into the United States.

The law that kept out Chinese immigrants was changed in 1949, and thereafter, Chinese were once again allowed to enter and to become American citizens. Other Asians have been permitted to become American citizens since 1952. Today, Asian- Americans are one of the fastest-growing ethnic groups in the United States. About 6.5 million Asians live in the United States, comprising about 2.5 percent of the population. Asian immigrants come from many very different countries, including the People's Republic of China, Japan, The Lao People's Democratic Republic, the Philippines, Vietnam, South Korea, Cambodia and Thailand.

Although most Asians in the United States emigrated relatively recently, they have become one of the most successful immigrant groups in the country. Large numbers of them study in the best American universities. They also have a higher average income than many other ethnic groups.

REFUGEES

After World War II, the United States began accepting refugees as a special group. The first refugees to the United States were Europeans who were uprooted by the horrors of war. Since then, the United States has taken in refugees from many places in the world. In 1956, thousands of Hungarians sought refuge in the United States after the Soviet Union crushed the attempt to establish a non- communist government in Hungary. After Fidel Castro took control of Cuba in 1959, the United States accepted 700,000 Cuban refugees. Many of these people settled together in communities around Miami, Florida. Again, in 1980, the United States accepted a special group of more than 110,000 Cuban refugees who came in crowded boats.

The United States has also accepted other groups of special political refugees. These include Southeast Asians, who were fleeing persecution after the end of the Vietnam War. Since 1975, the United States has accepted 750,000 refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia and The Lao People's Democratic Republic.

WHO IMMIGRATES?

The year 1965 marked a most important change in American immigration law. A new law signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson ended the old system of immigration that had favored northern and western Europeans. Under the new law, there is no consideration of people's country of origin, just as there have never been legal bars based on their race or their beliefs. Since 1965, the United States has accepted immigrants strictly on the basis of who applies first, within overall annual limits.

Soon after the 1965 law was passed, immigration patterns began to change. As recently as the 1950s, two-thirds of all legal immigrants came from Europe and Canada. By the 1980s, only one immigrant in seven came from these traditional sources. In the 1950s, immigrants from Asia accounted for only six percent of total immigration—or 150,000 in the entire decade. During the 1980s, 2.6 million Asian immigrants arrived, making up 44 percent of legal immigrants. The top points of origin from which new immigrants came in 1990 were Mexico (57,000), the Philippines (55,000), Vietnam (49,000), the Dominican Republic (32,000), Korea (30,000), China (29,000), India (28,000), the Soviet Union (25,000), Jamaica (19,000) and Iran (18,000).

The United States welcomes more immigrants than any other nation in the world. In 1990, its population included 18 million foreign-born people. But it cannot let everyone who wants to immigrate come at once. Under the Immigration Act of 1990, the total number of immigrants may not exceed 700,000 a year. But the new law also provides for exceptions that could increase that number significantly. For example, immediate family members of U.S. citizens would be admitted without regard to the cap, and more than 230,000 family members of U.S. citizens entered the country in 1990. And refugees—who numbered 97,000 in 1990—are also admitted without regard to the numerical limit.

The Immigration Act of 1990 also attempts to attract more skilled workers and professionals to the United States by reserving places specifically for them. And 10,000 places are reserved for entrepreneurs who promise to invest a minimum of $500,000 to start new businesses that will employ at least 10 people. People from countries whose immigrants were restricted by a previous immigration law are given special consideration. In 1990, 20,000 people entered under that category, most of them from Ireland, Canada, Poland and Indonesia. The new law also attempts to bring in more immigrants from countries that have supplied relatively few new Americans in recent years. It does this by providing some 50,000 "diversity visas" each year. About 9,000 people entered the United States in 1990 on diversity visas. The largest numbers came from Bangladesh, Pakistan, Peru, Egypt, and Trinidad and Tobago. Special provision is also made for Amerasian children born of American fathers stationed overseas. Some 3,000 nurses, most of them from the Philippines, also entered the country in 1990 under a law designed to alleviate the shortage of nurses in the U.S.

The United States also has a long tradition of taking in refugees, people fleeing from war or political persecution. But the United States cannot help all of the approximately 14 million

people in that category who need help from the international community. Every year, the executive branch of the government and the Congress jointly decide from which countries the United States will admit refugees. Other people are admitted on a case-by-case basis. In 1990, most of the 97,000 refugees came , from the Soviet Union, Vietnam, Eastern Europe, Iran, Afghanistan, Iraq, Cuba, and Ethiopia. The government also grants asylum to people who, when visiting the United States, ask to stay because of fear of persecution if they return to their home country. Not all requests for asylum are granted. The applicant must prove that his or her fears of persecution are well-founded. All together, 656,000 immigrants were admitted to the U.S. in 1990.

ILLEGAL IMMIGRANTS

Not all immigrants enter the United States legally. In 1986 there were an estimated 3 to 5 million people living in the country without permission, and the number was growing by about 200,000 a year.

Native-born Americans and legal newcomers worry about illegal immigrants. Many believe that illegal immigrants take jobs from citizens of the United States, especially from minority people and young people. Moreover, they can place a heavy burden on tax-supported social services. Some American employers have also exploited illegal workers, paying them less than the legal minimum wage and making them work under sub-standard conditions. The illegal immigrants cannot complain, for if they do, the employer can turn them over to the government law enforcement officials and have them sent out of the country.

In order to eliminate some of these problems with illegal immigration, the U.S. Congress approved a revision of American immigration policy in 1986. Under the new law, many illegal Immigrants who have been in the United States since 1982 can apply for legal residency that will eventually allow them to stay in the country permanently and give them full protection of the country's laws. In 1990, about 880,000 people gained legal status under this provision, and more than 2.5 million people are expected to "legalize." The new immigration law also provides protected status for illegal immigrants who have recently worked in U.S. agriculture and will also allow them to apply for permanent residency and citizenship. Historically, illegal immigrants have been very important in the harvesting of U.S. crops. While the new law brings significant benefits and protection to illegal immigrants who have been living in the United States, it also provides for strong measures to prohibit new illegal immigrants from entering the country and still imposes penalities on businesses that knowingly employ illegal aliens in the future.

IMMIGRATION TODAY

The 1965 change in the immigration laws—as well as rising illegal immigration—has changed the nature of the American population. It is not uncommon today to walk down the streets of the United States and hear Spanish spoken. In 1950, there were fewer than four million United States residents from

Spanish-speaking countries. Today, there are an estimated 17.6 million Hispanic people here. About 60 percent of the Hispanics in the United States have origins in Mexico, America's neighbor to the South. The other 40 percent come from a variety of countries, including El Salvador, the Dominican Republic and Colombia. Today, about 50 percent of the Hispanics in the United States live in California or Texas. Other states with large groups of Hispanics are Florida in the South, and Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado in the West.

In the past, Americans used to think of the United States as a "melting pot" of immigrants. A "melting pot" meant that as immigrants from many different cultures came to the United States, their old ways melted away and they became part of a completely new culture. The United States was likened to a big pot of soup, which had bits of flavor from each different culture. All of the different cultures were so well blended together that it formed its own new flavor.

Today, Americans realize that the simple "melting pot" theory is less true. Instead, different groups of people keep many of their old customs. Often groups of Americans from the same culture band together. They live together in distinctive communities, such as "Chinatowns" or "Little Italys"—areas populated almost exclusively by Americans of a single ethnic group—which can be found in many large American cities. Living in ethnic neighborhoods gives new Americans the security of sharing a common language and common traditions with people who understand them.

In time, however, people from different backgrounds mix together. They also mix with native-born Americans. Old traditions give way to new customs. The children of immigrants are often eager to adopt new, American ways. They often want to dress in American fashions, to speak English and to follow American social customs. By one estimate, about 80 percent of European immigrants marry outside their own ethnic groups by the time they reach the third generation. Third generation means that their great-grandparents were immigrants. Yet as successive generations become more "Americanized," they often retain significant elements of their ethnic heritage.

AMERICAN TRAITS

A look at immigration in the past and at immigration today shows where the American people came from. Understanding immigration also helps to explain some of the traits of the American people. For example, immigrants move to the United States because they are looking for a better life. It takes a lot of courage to leave behind everything that is familiar and come to a new country. Since before the independence of the United States, Americans have been a people willing to take risks and try new things. This willingness to strike out for the unknown takes an independence and an optimism that also is thought to be a characteristic of the American people today.

Immigrants also come to the United States because they differ from the majority of people surrounding them and because Americans also

are known to be generally accepting of people with different ideas.

Americans are also a people who are quick to learn and are open to new experiences. They have to be. Immigrants both today and in the past have a whole new world to learn about. They often have to learn everything from a new language to new social customs and new ways to make a living.

Immigrants also believe in the dream of the United States. They believe that by working hard and obeying the laws, they can have a better life. Often, Americans who have been here longer become less acutely aware of the rights and advantages that they have. Immigrants help native-born Americans to appreciate the good things to be found in the United States.

John F. Kennedy, who was president during the early 1960s, was the grandson of an Irish immigrant. Kennedy once said that the United States was "a society of immigrants, each of whom had begun life anew, on an equal footing. This is the secret of America: a nation of people with the fresh memory of old traditions who dare to explore new frontiers...."

Although there is sometimes friction and ill-feeling between new immigrants and people whose families have been Americans for generations, most Americans welcome newcomers. There is a popular feeling that immigrants have made America great and that each group has something to contribute. When President Bush signed the 1990 Immigration Act into law, he declared that its liberalized provisions would be "good for America."

Suggestions for Further Reading

Archdeacon, Thomas J.

Becoming American: An Ethnic History.

New York: Free Press, 1983.

Dinner stein, Leonard and David M. Reimers. Ethnic Americans: A History of Immigration and Assimilation. New York: Harper and Row, 1982.

Easterlin, Richard A., David Ward, William S.

Bernard and Reed Ueda.

Immigration.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982.

Michael Fix and Jeffrey S. Pass el. The Door Remains Open: Recent Immigration to the United States and A Preliminary Analysis of The Immigration Act of 1990.

Washington, DC, The Urban Institute, 1991.

Glazer, Nathan, ed.

Clamor at the Gates: The New American Immigration.

San Francisco: Institute for Contemporary Studies, 1985.

Morris, Milton D.

Immigration: The Beleaguered Bureaucracy. Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 1985.

AMERICAN REGIONALISM

On every coin issued by the government of the United States are found three words in Latin: E pluribus unum. In Engish this phrase means "out of many, one." The phrase is an American motto. Its presence on coins is meant to indicate that the United States is one country made up of many parts.

On one level of meaning, the "parts" are the 50 states that march across the North American continent and extend to Alaska in the north and Hawaii in the mid-Pacific. On another level, the "parts" are the nation's many different peoples, whose ancestors came from almost every area of the globe. On a third level, the "parts" are the environments or geographical surroundings of the United States. These environments range from the rolling countryside of the Penobscot River Valley in central Maine to the snowcapped peaks of the Cascade Mountains in western Washington state and from the palm-fringed beaches of southern Florida to the many- colored deserts of Arizona.

From the .standpoint of government, the United States is one single country, of course. Its center is the national government in Washington, D.C. There are many other signs that the United States is indeed united—a national language (English) and a national coinage, to name only two. The many parts remain, however, making it difficult in some ways to gain an idea of the United States as a whole.

How, then, do Americans think of the United States? They often speak of it as a country of several large regions. These regions are cultural rather than governmental units.

They have been formed out of the history, geography, economics, literature and folkways that all parts of a region share in common.

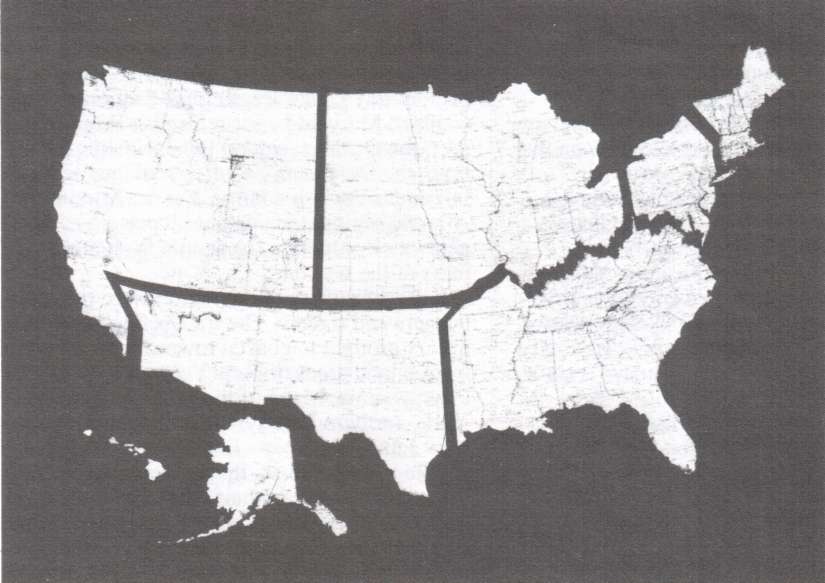

The development, over time, of culturally distinctive regions within a country is not unique to the United States. Indeed, in some countries, regionalism has acquired political significance and has led to domestic conflict. In the United States, however, regions have remained culturally defined, to the point that there are no easily demarcated borders between them. For this reason, no two lists of American regions are exactly alike. One common grouping creates six regions. They are:

• New England, made up of the northernmost five states along the Atlantic seaboard plus Vermont and parts of New York.

• The Middle Atlantic Region, composed of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland.

• The South, which runs from Virginia south to Florida and then west as far as central Texas. The region also takes in West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Louisiana and large parts of Missouri and Oklahoma.

• The Midwest, a broad collection of states sweeping westward from Ohio to Nebraska and southward from North Dakota to Kansas, including eastern Colorado.

• The Southwest, made up of western Texas, portions of Oklahoma, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and the southern interior area of California.

• The West, comprising Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Utah, California, Nevada, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, Alaska and Hawaii.

Defining the six main regions of the United States does not fully explain American regionalism. Within the main regions are several kinds of subregions. One type of subregion takes a river valley as its center. Thus, historians and geographers often write of the Mississippi Valley, the Ohio Valley or the Sacramento Valley. A second type of region is centered around mountain areas such as the

Blue Ridge country of Virginia or the Ozark country of Arkansas and Missouri.

Blue Ridge country of Virginia or the Ozark country of Arkansas and Missouri.

DIFFEREVT PLACES, DIFFERENT HABITS

What makes one region of the United States different from another? There are many answers to the question and the answers vary from place to place.

As a case in point, consider the role of food in American life. Most foods are quite standard throughout the nation. That is, a person can buy packages of frozen peas bearing the same label in Idaho, Missouri or Virginia. Cereals, rice, candy bars and many other foods also appear in standard packages. The quality of fresh fruits and vegetables generally does not vary from one state to another.

A few foods are not available on a national basis. They are simply regional dishes, limited to a single locale. In San Francisco, one popular dish is abalone, a large shellfish from Pacific waters. Another is a pie made of boysenberries, a cross between raspberries and blackberries. Neither abalone nor boysenberry pie is likely to appear on a menu in a New England restaurant, however. If you were to ask a Boston waiter for either dish, you might discover that he had never heard of it.

To take another example, consider the way Americans use the English language. For many years experts have been writing rules for standard American English, both written and spoken. With the coming of radio and television, this standard use of the English language has become much more generalized. But within several regions and subregions local ways of speaking, known as dialects, still remain quite strong.

In some farming areas of New England the natives are known for being people of few words. When they speak at all, they do so in short, rather choppy sentences and clipped words. Even in the cities of New England there

are definite styles of speech. Many people pronounce the word idea as "idear," or Boston as "Bahstun."

Southern dialect tends to be much slower and more musical. People of this region have referred to their slow speech as a "southern drawl." For instance, they commonly use "you-all" as the second person plural.

Regional differences extend beyond foods and dialects. Among more educated Americans, these differences sometimes center on attitudes and outlooks. An example is the stress given to foreign news in various local newspapers. In the East, where people look out across the Atlantic Ocean, papers tend to show greatest concern with what is happening in Europe, North Africa and western Asia. In the towns and cities that ring the Gulf of Mexico, the press tends to be more interested in Latin America. In California, bordering the Pacific Ocean, news editors give more attention to events in East Asia and Australia.

To explain the nature of regionalism more fully, it is necessary to take a closer look at each of these areas and the people who live there.

NEW ENGLAND

This hilly region is the smallest in area of all those listed above. It has not been blessed by large expanses of rich farmland or by a climate mild enough to be an attraction in itself. Yet New England can lay historic claim to having played a dominant role in the development of modern America. From the 17th century into the 19th century, New England was the nation's preeminent region with regard to economics and culture.

The earliest European settlers of New England were English Protestants of firm and settled doctrine. Many of them came in search of religious liberty, arriving in large numbers between 1630 and 1830. These immigrants shared a common language, religion and social organization. Among other things, they gave the region its most famous political form, the town meeting (an outgrowth of the meetings of church elders). In these meetings, most of a community's citizens gathered in the town hall to discuss and decide on the local issues of the day. Only men of property could cast a vote. Even so, town meetings allowed New Englanders a kind of participation in government that was not enjoyed by people of other regions before 1790. Town meetings remain a feature of many New England communities today.

From the first, New Englanders found it difficult to farm land in large lots, as was possible in the South. By 1750, many settlers had turned to other pursuits. The mainstays of the region became shipbuilding, fishing and trade. By the mid-19th century, New England possessed the largest merchant marine in the world. In their business dealings, New Englanders became known for certain traits, and are still thought of as being shrewd, thrifty, hardworking and inventive.

These traits were tested in the first half of the 19th century when New England became the center of America's Industrial Revolution. All across Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island, new factories appeared. These factories produced clothing, rifles, clocks and many other goods. Most of the money to run these industries came from the city of Boston,

then the financial heart of the nation.

One famous writer even referred to Boston as "the hub of the universe." And, in fact, the cultural life of the region was very strong. Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote novels such as The Scarlet Letter exploring the themes of sin and guilt. Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau wrote essays on the importance of following "one's own star." Older colleges and universities blossomed, while newer ones sprang up. New England's oldest schools of higher learning, such as Harvard University (Massachusetts), Yale University (Connecticut), Brown University (Rhode Island) and Dartmouth College (New Hampshire), were originally religious in their purpose and orientation, but gradually became more secular.

During this period, New England was also a source of pioneers for the westward movement. New Englanders transplanted themselves and many of their ideas to Ohio and the northern Midwest, to the Pacific Northwest and finally all the way to Hawaii. As some of the older stock of New England traveled onward, a newer stock gradually began to take its place. Immigrants from Ireland, Italy and Eastern Europe arrived in large numbers in the cities of the southern part of the region. Immigrants from French Canada moved into the mill towns of New Hampshire and Maine.

Despite a changing population, much of the older spirit of New England still survives today. It can be seen in the simple, woodframe houses and white church steeples that are features of many small towns. It can be heard in the horn blasts from fishing boats as they leave their harbors on icy, winter mornings. Living may be easier in some other regions, but most New Englanders envy none of them. "However mean your life is, meet it and live it" wrote Henry David Thoreau; "do not shun it and call it hard names."

Thoreau's advice has a new meaning these days. Many industries have left the region and moved to places where goods can be made more cheaply. Clothing mills, shoe plants, clock factories and other businesses have shut their doors for the last time. In more than a few factory towns, skilled workers have been left without Jobs. Yet there are also signs of hope for a brighter future. One of them is the growth of newer industries such as electronics. The electronics industry produces radios, television sets, computers and similar items.

Whatever the future brings, there is not much doubt that the region will face it with pride. True New Englanders do not think of their hills and valleys merely as home but also as a center of civilization. A woman from Boston was once asked why she rarely traveled. "Why should I travel," she replied, "when I'm already there?"

THE MIDDLE ATLANTIC REGION

If New England supplied the spirit of invention, the Middle Atlantic region provided 19th-century America with its muscle. The largest states of the region, New York and Pennsylvania, became major centers of heavy industry. Here were most of the factories that produced iron, glass and steel. Here, too, were a number of the nation's greatest cities.

The Middle Atlantic region had been settled from the first by a much wider range î people than New England. Dutch made their homes in the woodlands along the lower Hudson River in what is now New York. Swedes established tiny communities in present-day Delaware. English Catholics founded Maryland and an English Protestant sect, the Quakers, settled Pennsylvania. In time, the Dutch and Swedish settlements all fell under English control. Yet the Middle Atlantic region remained an important early gateway to America for people from many parts of the world.

Early settlers of the region were mostly farmers and traders. The traders dealt mainly in furs brought to coastal towns by trappers from inland areas of New York and Pennsylvania. Many of the farmers of New York, northern Pennsylvania and northern New Jersey were New Englanders. These people had moved south and west in search of better land, bringing their way of life with them. Another large group of farmers in Pennsylvania came from Germany. These people included the Mennonites, members of; Protestant sect that believed in living simply.

In the early years, the Middle Atlantic region was often used as a bridge between New England and the South. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a mid-point between the northern and southern colonies, became the home of the Continental Congress, the group that led the fight for independence. The same city was the birthplace of the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and the United States Constitution in 1787.

At about the same time, some eastern Pennsylvania towns first tapped the iron deposits around Philadelphia. Steam soon replaced water as a source of power, creating ; greater need for iron. Heavy industries sprang up throughout the region because of nearby natural resources. Several mighty rivers, such as the Hudson and the Delaware, were transformed into vital shipping lanes. Cities along these waterways—New York on the Hudson, Philadelphia on the Delaware, Baltimore on Chesapeake Bay—expanded int< major urban areas.

Industries needed workers and many of them came from overseas. Late in the 19th century, the flow of immigrants to America swelled to a steady stream. In the words of the region's most beloved poet, Walt Whitman, th United States became "not merely a nation but a teeming nation of nations." New York City was port of entry for most newcomers. In the 1890s and early 1900s, millions of them sailed past the Statue of Liberty in New York harbor on the way to a fresh start in the United States.

Today New York ranks as the nation's largest city, its hub of finance and a cultural center for the United States and the world. It still bears traces of its Dutch past in the names of neighborhoods such as Harlem. Yet very few faces on the city's streets are Dutch faces. New York has the largest Jewish population î any city in the world. About three out of 10 of the faces one sees are likely to be those of black Americans, many of whose families moved to the city long ago from the South. Another three out of 10 New Yorkers come from overseas, nowadays from a mixture of countries that include Jamaica and South Korea, Haiti and Vietnam.

Date: 2015-02-28; view: 1802

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| PROSPERITY AND CIVIL RIGHTS 1 page | | | PROSPERITY AND CIVIL RIGHTS 3 page |