CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

PROSPERITY AND CIVIL RIGHTS 1 page

From 1945 until 1970, the United States enjoyed a long period of economic growth, interrupted only by brief and fairly mild recessions. For the first time, the great majority of Americans could enjoy a comfortable standard of living. By 1960, 55 percent of all households owned washing machines, 77 percent owned cars, 90 percent had television sets and nearly all had refrigerators.

At the same time, the United States was moving slowly in the direction of racial justice. In 1941, the threat of black protests persuaded President Roosevelt to ban discrimination in war industries. In 1948, President Truman ended racial segregation in the armed forces and in all federal agencies. In 1954, in the decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that segregation in the public schools was unconstitutional; nevertheless, southern states continued to resist integration. In 1955, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. led a boycott of segregated public transportation that eventually ended segregation on city buses in Montgomery, Alabama. In 1957, the governor of Arkansas tried to prevent black students from enrolling an all-white high school in the state capital of Little Rock. To enforce obedience to the law requiring integration, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent in federal troops.

That same year, Americans were jolted to learn that the Soviet Union had launched Sputnik, the Earth's first man-made satellite. This was a shock for the United States, a nation that had always taken pride in its technological expertise. In response, the American federal government increased efforts already underway to produce a satellite and spent more money în education, especially in the sciences.

NEW FRONTIER AND GREAT SOCIETY

In 1960, Democrat John F. Kennedy was elected president. Young, energetic and handsome, Kennedy promised to "get the country moving again"; to forge ahead toward a "New Frontier." But one of Kennedy's first foreign policy ventures was disaster. In an effort to overthrow the Communist dictatorship of Fidel Castro in

Cuba, Kennedy supported an invasion of the island nation by a group of Cuban exiles who had been trained by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). In April 1961 the exiles landed at the Bay of Pigs and were almost immediately captured.

In October 1962, observation planes discovered that the Soviet Union was installing nuclear missiles in Cuba, close enough to strike American cities in a matter of minutes. Kennedy imposed a blockade on Cuba. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev finally agreed to remove the missiles, in return for an American promise not to invade Cuba.

In April 1961, the Soviets scored another triumph in space: Yuri Gagarin became the first man to orbit the Earth. President Kennedy responded with a pledge that the United States would land a man on the moon before the end of the decade. In February 1962, John Glenn made the first American orbital flight, and he was welcomed home as a hero—much as Charles Lindbergh had been celebrated 35 years earlier after he made the first nonstop solo flight across the Atlantic. It took $24 thousand million and years of research but Kennedy's pledge was fulfilled in July 1969, when Neil Armstrong stepped out of the Apollo 11 spacecraft onto the surface of the moon.

In the 1960s, Martin Luther King, Jr. led a nonviolent campaign to desegregate southern restaurants, interstate buses theaters and hotels. His followers were met by hostile police, violent mobs, tear gas, fire hoses and electric cattle prods. The Kennedy administration tried to protect civil rights workers and secure voting rights for southern blacks.

In 1963 Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas. Kennedy was not a universally popular president, but his death was a terrible shock to the American people.

The new president was Lyndon Johnson, who had been vice president under Kennedy and succeeded to the office on the death of the president. He persuaded Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed racial discrimination in public accommodations and in any business or institution receiving federal money. Johnson was elected to a new term with widespread popular support in 1964. Encouraged by a great election victory, Johnson pushed through Congress many social programs: federal aid to education, the arts and the humanities; health insurance for the elderly (Medicare) and for the poor (Medicaid); low- cost housing and urban renewal. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 finally enabled all black Americans to vote. Discrimination in immigration was also ended: national origins quotas were abolished allowing a great increase in entry visas for Asians.

Although most Americans had by now achieved affluence, Michael Harrington's book The Other America (1962) identified persistent pockets of poverty—in urban slums, in most black neighborhoods and among the poor whites of the eastern Appalachian mountains. President Johnson responded with his "War on Poverty," which included special preschool education for poor children, vocational training for school dropouts and community service jobs for slum youths.

VIETYAM WAR

American involvement in Vietnam did not begin with President Johnson. When Communist and nationalist rebels fought French colonialism in Indochina after World War II, President Truman sent military aid to France. After the French withdrew from Southeast Asia in 1954, President Eisenhower dispatched American advisers and aid to help set up a democratic, pro-Western government in South Vietnam. Under President Kennedy, thousands of military officers trained South Vietnamese soldiers and sometimes flew Vietnamese warplanes into combat.

In August 1964, two American destroyers sailing in the Gulf of Tonkin reported attacks by North Vietnamese torpedo boats. President Johnson launched air strikes against North Vietnamese naval bases in retaliation. The first American combat soldiers were sent to Vietnam in March 1965. By 1968, 500,000 American troops had arrived. Meanwhile, the Air Force gradually stepped up Â-52 raids against North Vietnam, first bombing military bases and routes, later hitting factories and power stations near Hanoi.

Demonstrations protesting American involvement in this undeclared and, many felt, unjustified war broke out on college campuses in the United States. There were some violent clashes between students and police. In October 1967, 200,000 demonstrators demanding peace marched on the Pentagon in Washington.

At the same time, unrest in the cities also erupted, as younger and more militant black leaders were denouncing as ineffectual the nonviolent tactics of Martin Luther King. King's assassination in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1968, triggered race riots in over 100 cities. Business districts in black neighborhoods were burned, and 43 people were killed—most of them black.

Ever increasing numbers of Americans from all walks of life opposed the involvement of the United States in the war in Indochina, and in the 1968 election, President Johnson faced strong challenges. On May 31, facing a humiliating defeat at the polls and a seemingly endless conflict in Vietnam, Johnson withdrew from the presidential race and offered to negotiate an end to the Vietnam War. The voters narrowly elected Republican Richard Nixon. As president Nixon appealed to "Middle America"— the "great silent majority" who were unhappy with violence and protest at home.

In Indochina, Nixon pursued a policy of "Vietnamization," gradually replacing American soldiers with Vietnamese. But heavy bombing of Communist bases continued, and in the spring of 1970 Nixon sent American soldiers into Cambodia. That action caused the most massive and violent campus protests in the nation's history. During a demonstration at Kent State University in Ohio, National Guardsmen killed four students.

Then, as the American people perceived that the war was being ended, the situation quite suddenly changed: Quiet returned to the nation's colleges and cities. By 1973, Nixon had signed a peace treaty with North Vietnam, brought American soldiers home, and ended conscription. Students began rejecting radical politics and generally became more oriented

toward individual careers. Many blacks were still living in poverty, but many others were finally moving into well-paid professions. The fact that many big cities—Cleveland, Newark, Los Angeles, Washington, Detroit, Atlanta— had elected black mayors contributed to the easing of urban tensions.

DECADES OF CHANGE

Political activism however, did not disappear in the 1970s—it was rechanneled into other causes. Some young people worked for the enforcement of antipollution laws or joined consumer-protection groups or campaigned against the nuclear power industry. Following the example of blacks, other minorities— Hispanics, Asians, American Indians, homosexuals— demanded a broadening of their rights.

Women had been gradually moving into the labor force since World War II, and in the 1970s a women's liberation movement pressed for legal abortion, day-care centers, equal pay and jobs for women. In 1973, the Supreme Court banned most restrictions on abortion, but that ruling only made more difficult a furious national debate: feminists defended abortion as a Constitutional right; others denounced it as the destruction of innocent life.

President Nixon achieved two major diplomatic goals: re-establishing formal relations with the People's Republic of China and negotiating the first Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I) with the Soviet Union. In the 1972 election, he easily defeated George McGovern, a liberal antiwar Democrat.

During the campaign, however, five men were arrested for breaking into the Democratic party headquarters at the Watergate building in Washington, D.C. Journalists investigating the incident discovered that the burglars were employed by President Nixon's reelection committee. The White House made the scandal worse by trying to cover up its connection with the break-in. In July 1973, it was revealed that President Nixon had recorded his office conversations concerning the Watergate affair. Congressional committees, special prosecutors, federal judges and the Supreme Court all demanded that the President surrender the recordings, and after prolonged resistance he finally made them public. The tapes revealed that President Nixon was directly involved in the cover up. By the summer of 1974, it was clear that Congress was likely to impeach and to convict the president. On August 9, Richard Nixon became the only American president to resign his office.

Republican Gerald Ford, who succeeded to the presidency on the resignation of Richard Nixon, was likable and conciliatory. Ford did much to restore the trust of the citizens, though some voters never forgave him for pardoning his former boss, Richard Nixon. The 1976 election was won by Democrat Jimmy Carter, former governor of Georgia. Carter had limited political experience, but many voters now preferred an "outsider"—someone who was not part of the Washington establishment.

Precisely because he was an outsider, President Carter had difficulty working with Congress. He also could not control the chief economic problem of the 1970s—inflation. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) had been increasing the cost of oil since 1973, and those increases fueled a general rise in prices. By 1980, inflation had soared to an annual rate of 13.5 percent, and the nation was experiencing a period of economic difficulty. Carter signed a second Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT II) with the Soviet Union, but it was never ratified by the Senate after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979. He also seemed ineffectual in the face of another crisis: In 1979, Iranian radicals stormed the United States embassy in Teheran and held 53 Americans hostage. Carter's greatest success was the negotiating of the Camp David Accord between Israel and Egypt, which led to an historic peace treaty between the two nations.

In the presidential race of 1980, American voters rejected Carter's bid for a second term, and elected Ronald Reagan, a conservative Republican and former governor of California. As a result of the election, the Republican party gained a majority in the Senate for the first time in 26 years. By giving Ronald Reagan an overwhelming election victory, the American public expressed a desire for change in the style and substance of the nation's leadership. Throughout his presidency, Reagan demonstrated the ability to instill in Americans pride in their country, and a sense of optimism about the future.

If there was a central theme to Reagan's national agenda, it was his belief that the Federal Government had become too big. Upon taking office in 1981, the administration's immediate problems were stagnant economic growth, high inflation and soaring interest rates. Reagan soon began a drastic reshaping of the federal budget, directed largely at domestic- spending programs. Reagan's domestic program was rooted in the belief that the nation would grow and prosper if the power of the private economic sector were unleashed. The administration also sought and won significant increases in defense spending.

Despite a growing federal budget deficit, by 1983 the economy as a whole had rebounded, and the United States entered into one of the longest periods of sustained economic growth since World War II. Presiding, like Eisenhower, over a period of relative peace and prosperity at the end 6f their first term, President Reagan and Vice President George Bush overwhelmingly won reelection in 1984. They carried 49 of 50 states in defeating the Democratic party ticket of former Vice President Walter Mondale and Geraldine Ferraro, who was the first woman in U.S. history to run as a vice presidential candidate.

In foreign policy, President Reagan sought a more assertive role for the nation. The United States confronted an insurgency in El Salvador, and the Sandinista regime in Nicaragua. In 1983 U.S. forces landed in Grenada to safeguard American lives and to oust a regime which took power after the assassination of the country's elected Prime Minister. The U.S. also sent peace-keeping troops to Lebanon, in an effort to bolster a moderate, pro-Western government. The mission ended tragically when 241 American Marines were killed in a terrorist bombing. In 1986, U.S. military forces struck targets in Libya, in retaliation for Libyan-instigated attacks on American personnel in Europe. Additionally, the United States and other Western European nations kept the vital Persian Gulf oil-shipping lanes open during the Iran-Iraq conflict, by escorting tankers though the war zone.

U.S. relations with the Soviet Union during the Reagan years fluctuated between political confrontation and far-reaching arms control agreements. In December, 1987, the U.S. and the Soviet Union signed the Intermediate- Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which provided for the elimination of a whole category of ballistic missiles. However, efforts to make major cuts in other strategic weapons systems were not concluded, in large part due to the Reagan Administration's strong desire to develop the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), commonly known as the "star wars" ballistic missile defense system.

On January 28, 1986, after 24 successful flights, the space shuttle Challenger exploded 73 seconds after liftoff, killing all on board. The Challenger tragedy was a reminder of the limits of technology at a time when another technological revolution, in computers, was rapidly transforming the way in which millions of Americans worked and lived. It was estimated that by mid-decade Americans possessed more than 30 million computers. By late 1988, however, the U.S. successfully launched a redesigned space shuttle Discovery, which deployed a satellite in the first shuttle flight since the Challenger disaster.

The Reagan Administration suffered a defeat in the November 1986 congressional elections when the Democrats regained majority control of the U.S. Senate. However, the most serious issue confronting the administration at that time was the revelation that the U.S. had secretly sold arms to Iran in an attempt to win freedom for American hostages held in Lebanon, and to finance the Nicaraguan contras during a period when Congress had prohibited such aid. During the Congressional hearings which followed, the country addressed fundamental questions about the public's right to know, and the proper balance between the executive and legislative branches of government. Despite these problems, President Reagan enjoyed unusually strong popularity at the end of his second term of office.

Reagan's successor, George Bush, benefited greatly from the popularity of the former president. In the 1988 election, Bush defeated the Democratic Party's nominee, Michael Dukakis, by a wide margin, becoming the first sitting vice president since 1836 to be elected to the Presidency. During his campaign, Bush promised to continue the economic policies of the Reagan Administration. He echoed some of Reagan's positions on social issues, such as his strong stand against abortion, while quieting some of Reagan's critics with a call for a "kinder, gentler nation," and by stressing a commitment to be the "education president."

The U.S.-Soviet dialogue continued to broaden and deepen during the first year of the Bush Administration, at a time of ferment and remarkable political change in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe—symbolized most eloquently by the opening of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. In the two years following that event, the world witnessed the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of its dominating influence in Eastern Europe. The Bush Administration promoted the concept of a "new world order," based on a new set of international realities, priorities, and moral principles.

The idea of a "new world order" faced its first test when Iraq invaded oil-rich Kuwait in August 1990. In January 1991, when Iraq did not comply with United Nations resolutions designed to force its withdrawal from Kuwait, U.S. military forces, as part of a multinational coalition, liberated Kuwait in a swift and decisive victory. Immediately after the war, th< Bush Administration took the lead in bringing together the age-old antagonists in the Middle East for a series of unprecedented peace conferences. As the 1992 elections approached President Bush focused his attention more on domestic issues and problems such as economic recession, unemployment, crime, education, and health care.

IMMIGRATION TO AMERICA

IMMIGRATION TO AMERICA

The story of the American people is the story of immigrants. The United States has welcomed more immigrants than any other country in the world. More than 75 percent of all people who ever moved from their homeland settled in the United States. Since its early days, the United States has accepted more than 50 million newcomers.

Migration to America began more than 20,000 years ago. At that time, groups of wandering hunters followed herds of game (animals hunted for food) from Asia to America across a northern land bridge where the Bering Straits are today. These people settled throughout North and South America. They are considered to be the only "native" Americans. By the time Christopher Columbus, an Italian navigator employed by the Spanish monarchs, "discovered" the American continents in 1492, about one million Native Americans lived in the area that later became the United States. Today, there are about 1.4 million Native Americans in the United States (0.6 percent of the total population).

Groups of Spanish settlers established outposts in what is now Florida, in the southeastern United States, during the 1500s, and a small French colony was founded on the

New World's northeastern seacoast (Maine) in 1604. In 1607, Great Britain founded its first permanent North American settlement: Jamestown, in the colony of Virginia—now a state located along the southeastern coast of the United States. Communities of Dutch, Swedish and German settlers were also established along North America's Atlantic coastline.

Why did these early European colonists risk a dangerous ocean journey and great hardship to settle in an unknown land? They were brought by the same desires that still bring immigrants today. The first European settlers were seeking land, wealth and freedom—a better life. Some colonists came to America to find religious freedom; one example of these was a group of English religious dissenters called Pilgrims. In 1620, the Pilgrims founded the colony of Plymouth,

in what is now Massachusetts. The Pilgrims disagreed with the religious teachings of the official Church of England, and they came to America to be free to worship as they pleased.

BRITISH NORTH AMERICA

By 1700, Great Britain had established clear colonial dominance over that part of North America which later became the eastern United States. Thirteen separate British colonies, governed indirectly by the British Parliament, provided raw material for the "mother country" and bought goods produced in Britain. Though people of many European nationalities lived in the colonies, the official language spoken was English and British laws and social institutions prevailed.

Over time, the colonial inhabitants of North America became increasingly dissatisfied with the power of Great Britain's king and Parliament to control their lives. They believed Britain's taxes to pay for colonial administrative expenses to be an unjustified burden, and they feared that the broad degree of personal freedom which existed in the colonies might be curtailed. This situation led, in 1775, to the outbreak of hostilities between British military and colonial marksmen and to the colonists formally declaring their independence from Great Britain in 1776. The American Revolutionary War (1775- 1783) established the independence of the United States.

Even during the Revolutionary War, immigration from many countries continued, and in 1776 Thomas Paine, an Englishman who emigrated to America in 1774, wrote "Europe, not England, is the parent country to America." These words encouraged immigrants from Holland, Germany, France, Switzerland, Spain and Scotland to come to the New World. In 1780, three out of every four Americans were of English or Irish background. Most of the rest came from other countries in northern and western Europe.

UNWILLING IMMIGRANTS

Among the flood of immigrants to North America, one group of people came unwillingly. Tbese were Africans. About 500,000 Africans were brought to the colonies as slaves between 1619 and 1808. This trade began as an outgrowth of the Spanish traffic in slaves between Africa and South America. Importing slaves to the United States became a crime in 1808, 21 years after the adoption of the Constitution of the United States in 1787, but slavery itself was not eliminated until after the Civil War (1861-1865). By 1810, there were 7.2 million people in the United States, of which 1.2 million were slaves and 186,768 free blacks. In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves in areas of the nation which were in rebellion. Slavery was completely abolished in 1865, with the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. Some blacks had gained their freedom before this time. Today, black Americans compose about 12 percent of the total population.

THE GOLDEN DOOR

Between 1840 and 1860, the United States received its largest wave of immigrants to date. In Europe, famine, poor crops, rising populations and political unrest caused an estimated five million people to leave their homelands each year. Between 1845 and 1850, the Irish people faced famine. The potato crop, upon which the Irish depended for subsistence, suffered blight for five years, and about 750,000 Irish starved to death. Many of those who survived left Ireland for the United States. In one year alone—1847—118,120 Irish people emigrated to the United States. By 1860, one of every four people in New York City had been born in Ireland. Today in the United States there are more than 13 million Americans of Irish ancestry.

During the Civil War, the federal government encouraged immigration from Europe, especially from the German states, by offering grants of land to those immigrants who would serve as troops in the armies of the North. In 1865, about one in five Northern soldiers was a wartime immigrant. Today, fully one-third of Americans have German ancestors.

Until about 1880, most immigrants came from northern and western Europe. Then a great change occurred. More and more immigrants began coming from countries in eastern and southern Europe. They were Poles, Italians, Greeks, Russians, Hungarians and Czechs. By 1896, more than half of all immigrants were from eastern or southern Europe.

One group of people who came to the United States during this period were Jews. The first Jewish people actually settled in North America as early as 1654, but Jews did not move to the United States in great numbers until the 1880s. During the 1880s, Jews suffered fierce pogroms (massacres) throughout eastern Europe. Many thousands of Jews escaped an almost certain death by coming to the United States. Between 1880 and 1925, about two million Jews immigrated here. Today, there are about 5.7 million Jewish Americans living in the United States, comprising about 2.2 percent of the total population. In certain states, such as New York, a state along the mid-Atlantic coast, their numbers are higher, and they account for more than 10 percent of the population.

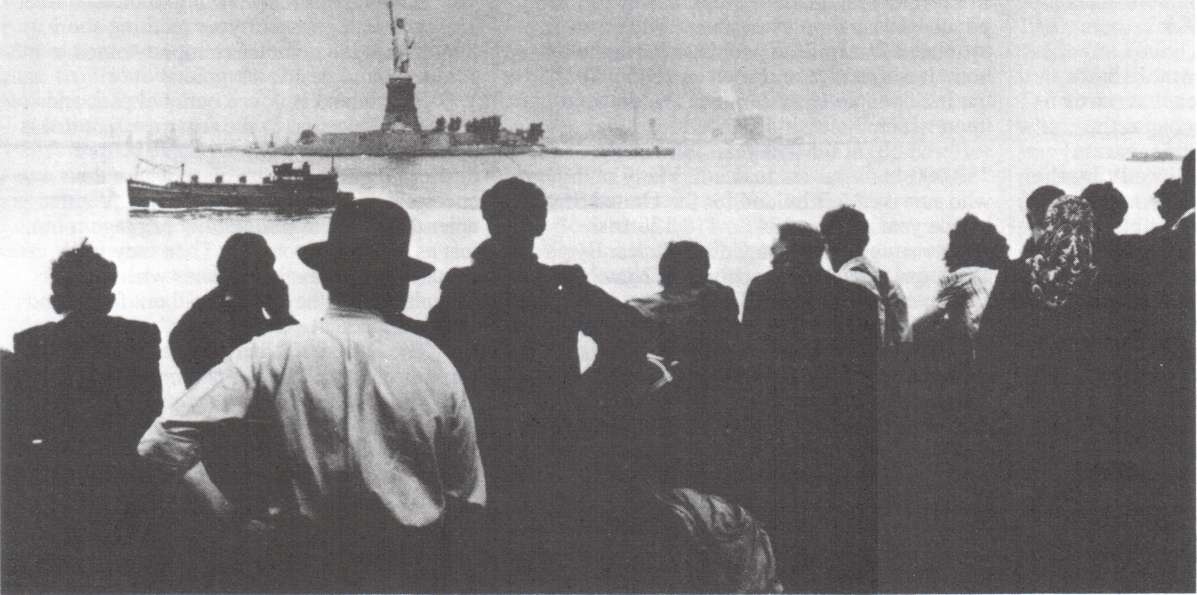

During the late 1800s, so many people were entering the United States that the government was having trouble keeping records on all of these people. To solve this problem, the government opened a special port of entry in New York harbor. This port was called Ellis Island. Between 1892, when Ellis Island was opened, and 1954, when it closed, more than 20 million immigrants entered the United States through this port of entry. During its busiest days, almost 2,000 immigrants a day passed through. Today, about half of all Americans have ancestors who entered the United States by way of Ellis Island.

The United States was becoming known throughout the world as a refuge and a welcoming place for people of many nations. In 1886, as a gesture of friendship, France gave the United States the Statue of Liberty, which stands on an island in the harbor of New York City, near Ellis Island. Since that time, the Statue of Liberty has been one of the first sights many immigrants to the United States

see. It is a symbol of the hope and freedom that the country offers. The words etched on the base of the statue have been the inspiration for people in many lands who hope to come to the United States: "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free. The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless tempest-tossed to me. I lift my lamp beside the golden door!"

Ellis Island is now a national park and historical museum. In the first year that it was open, more than a million people visited— many of them to see the place where their ancestors entered the United States. Visitors enter the museum through the baggage room, just as their ancestors did. Then they walk upstairs and sit on the benches where new arrivals waited their turn to fill out forms and undergo medical examinations.

The Statue of Liberty began lighting the way for new arrivals just at a time when native- born Americans began worrying that the United States was being overrun by immigrants. In the 30 years between 1890 and 1920, more than 18.2 million immigrants flooded America's shores. By 1910, 14.5 percent of all residents were foreign-born; today, about 6.2 percent of all American residents are foreign-born.

How could the United States absorb so many foreigners? Many citizens worried that these new Americans would take away their jobs. Citizens began demanding that the Congress limit the number of immigrants.

LIMITS ON NEWCOMERS

Gradually, responding to the demands of American citizens, Congress began to pass laws barring the entry of certain types of immigrants. The United States refused to accept immigrants who were prostitutes, convicts, insane, mentally retarded, beggars, revolutionaries, persons suffering from serious diseases and children without at least one parent.

These rules only held back one percent of all immigrants. So Congress tried to deny entry to immigrants who could not read or write. However, President Grover Cleveland, who was then president of the United States, refused to give his approval. Some people protested that the United States was being overrun by "inferior" races. But President Cleveland wrote: "Within recent memory...the same thing was said of immigrants who, with their descendants, are now numbered among our best citizens."

In 1924, Congress passed the Reed- Johnson Immigration Act. This law, which reflected the fears and prejudices of an "older" wave of immigrants from northern Europe, set limits on how many people from each foreign country would be permitted to immigrate to the United States. The number of people allowed from each country was based on the number of people from that country already living here. This system was designed primarily to limit immigration from southern and eastern Europe. For example, 87 percent of the immigration permits went to immigrants from Great Britain, Ireland, Germany and Scandinavia.

Date: 2015-02-28; view: 1740

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| HISTORY: 1929 TO THE PRESENT | | | PROSPERITY AND CIVIL RIGHTS 2 page |