CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

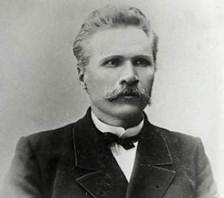

Unit 14: Dmytro Yavornytsky

This theme is dealt with in a lot of historical sources. The following citation is to illustrate this:

“Dmytro Yavornytsky was a noted Ukrainian historian, archeologist, ethnographer, folklorist, and lexicographer. He was one of the most prominent researchers of the Ukrainian Cossacks, especially the Zaporozhian Cossacks (or Zaporozhian Host), and the author of their first general history. In recognition of his many contributions to the preservation of Zaporozhian history and culture, he is widely known as "the Father of the Zaporozhians".

He was educated at Kharkiv, Kazan, and Warsaw universities but his academic career was repeatedly interrupted by the Imperial Russian authorities for political reasons.

As a historian, Yavornytsky displayed a romantic-antiquarian approach to his subject and was a conscious follower of his predecessor, the Ukrainian historian, Mykola Kostomarov. His major work was the History of the Zaporozhian Cossacks which was published in Russian in three volumes between 1892 and 1897. In this and in his other works, he portrayed the Zaporozhians as representatives of Ukrainian liberty.

As an ethnographer, folklorist, and lexicographer, Yavornytsky was also a pioneer. He made numerous contributions to the historical geography of the Zaporozhian lands, and mapped in detail the Dnieper River rapids with the locations of the various Zaporozhian Siches, or fortified headquarters. He published a large collection of Ukrainian folksongs. He increased the holdings of the Yekaterinoslav Museum from 5,000 to 80,000 items.

During the Stalin repressions of the 1930s, Yavornytsky was prevented from publishing and had to keep a very low profile.

His death passed unnoticed both in the USSR and in the wider world. The Yekaterinoslav Museum was eventually renamed in his honour and he was partially rehabilitated during the Khrushchev and Shelest eras. Materials about him began to appear, and in the early 1970s, a four volume collection of his works was prepared for publication. Political circumstances again prevented this from happening, but with the advent of the Perestroika reforms in the late 1980s, new materials began to appear and his major works were republished. At that time, his History of the Zaporozhian Cossacks was reprinted both in Russian and in Ukrainian (1990–91). The Ukrainian edition contains numerous additional illustrations. In 2004, the first volume of his Collected Works in Twenty Volumes was published. The first ten volumes of this collection will contain his historical, geographical, and archeological works, the second ten volumes, his works on folklore, ethnography, and language. …”

The complete version of this text is at:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dmytro_Yavornytsky

Assignments

1) Give Ukrainian equivalents to the following:

Researcher, interrupted, predecessor, elderly, holdings, honour, rehabilitated, circumstances

2) Give definitions to the following:

Political reasons, enthusiast, origins, demise, portray, pioneer, volume

3) Answer the questions on the text:

1. What were the main objects for Yavornytsky’s researches?

2. Where was he educated?

3. What is Yavornytsky’s main work?

4. During the Stalin repressions he was prevented from publishing, wasn’t he?

5. When did publications about Yavornytsky begin to appear?

4) Speak on this issue adding extra information from other sources.

5) What do you know about Dmytro Yavornytsky?

5) What do you know about Dmytro Yavornytsky?

Date: 2015-02-28; view: 1541

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Unit 12: Hetmanate | | | Dangerous Elegance A History of High-Heeled Shoes |