CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Changes in Demand

Demand

As winter ends, many clothing stores find that their inventories (stock of goods) of winter clothes are too large. How can they encourage people to buy winter items in March? Run a sale? That would be a good suggestion, because people will buy winter clothing in the spring if the price is low enough.

The Law of Demand. Demand is a consumer's willingness and ability to buy a product or service at a particular time and place. If you would like a new pair of athletic shoes but can't afford them, economists would describe your feeling as desire, not demand. But if you had the money and were ready to buy shoes, you would be included in their calculations.

The law of demand formally describes the rationing effect of prices. It says that other things being equal, more items will be bought at a lower price than at a higher price.

Suppose that your two friends, Lauren and Ralph, noticed that everyone, from babies to grandparents, wears T-shirts with colorful designs, the name of their school, favorite team, jokes—just about anything. They decided to start a T-shirt business and sell shirts with their school name and mascot. They also would design and sell shirts for special school events—homecoming, graduation.

Before they invested in T-shirts, silk-screening equipment, and the other supplies they would need, Lauren and Ralph conducted a survey to see if students would be interested in their shirts. Each student was asked the following question: "Would you spend $5.00 for a special homecoming T-shirt?" They repeated this question with different prices up to $20.00.

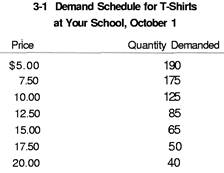

The Demand Schedule. The results of the survey were compiled in a demand schedule, Table 3-1, showing the quantities of a product that would be purchased at various prices at a given time.

The survey results illustrate the law of demand in action. According to the demand schedule, the number of shirts that students were ready, willing, and able to buy was greater at lower prices than at higher prices. This seems to be common sense. More people are willing to buy T-shirts, and anything else, at lower prices. And fewer people are willing to buy things at higher prices.

Price has a major effect on the quantity of any good or service consumers will demand. The availability of substitutes, and the economic principle of diminishing marginal utility further explain the relationship between price and quantity demanded.

• Substitutes. In many instances you can substitute one product for another. Some stores, for example, sell frozen yogurt as well as ice cream. Many ice cream lovers would buy frozen yogurt if the price of ice cream increased. Similarly, one's decision to have hamburger, steak, or fish often depends on the price of those substitutes. Economists describe this as the substitution effect of price changes on quantity demanded.

• Diminishing marginal utility. You might love pizza, but there is a limit to the amount you will eat at one time. Sooner or later, you'll reach a point where enjoyment decreases with every bite, no matter how low the cost. What is true of pizza applies to most everything. Even Calvin got enough of his "chocolate frosted sugar bombs." Economists call this diminishing marginal utility. Utility refers to the usefulness of something. Thus diminishing marginal utility is economists' way of describing the point reached when the next item consumed is less satisfying than the one before.

Diminishing marginal utility helps to explain why lower prices are needed to increase the quantity demanded. Since your desire for a second slice of pizza is probably less than it was for the first, you are not likely to buy more than one, except at a lower price. In most cases, you will choose to use your limited resources on something other than pizza to maximize the utility you receive from the money (get the most out of your money) you have to spend on a second slice of pizza.

A demand curve is a graph of the demand schedule. The curve in Figure 3-2 shows the relationship between the price of T-shirts and the quantity buyers were willing to purchase for homecoming. It lets Lauren and Ralph estimate what the demand would be for prices falling between the ones they surveyed. Although students were not questioned about how many shirts they would buy at $16.00, the curve lets them estimate the number would be about 55.

Changes in Demand

The relationship between price and the quantity of an item people will purchase is one aspect of demand. But sometimes things happen that change the demand for an item at each and every price. When this occurs, economists say demand changes-it increases or decreases. What are some of the factors that would cause the demand for T-shirts, or any other product, to increase or decrease?

• Prices of Substitutes. What will happen to the demand for sweatshirts if the price of T-shirts increases? When two goods satisfy similar needs, they are described as substitutes. A change in the price of one item will result in a shift in the demand for a substitute. Tapes and CDs are close substitutes. If the price of CDs goes up dramatically, people will tend to substitute audiotapes for CDs, and the demand for audiotapes will increase at every price.

• Prices of Complementary Goods. What will happen to the demand for T-shirts when the price of jeans falls? Goods that often are purchased together, like T-shirts and jeans, are complementary. According to the law of demand, if the price of jeans falls, the number of jeans purchased will increase. Since people often buy jeans and T-shirts together, demand for T-shirts should increase.

What are some other factors that might cause the demand for these friends' T-shirts to increase or decrease at each and every price? The following is a brief list of factors that might affect the demand:

• Change in the weather or season. The demand for a "spring break" T-shirt may be much greater than a homecoming shirt. Why?

• Change in income. If the economy improves and most people have more money to spend, they are often willing to pay higher prices for the same quantities. During a recession the opposite is true. Economists describe this as the income effect of demand.

• Number of Buyers. The quantity of an item demanded also is affected by the size of the population a market serves. The demand for popcorn inside a movie theater is greater than outside because popcorn and movies go together.

• Change in styles, tastes, habits. Obviously, fashions change. It's possible that T-shirts—like bell bottoms and platform shoes—will disappear, only to return in 2015.

• Future Expectations. Will the price go up or down in the future? Future expectations will not impact the

demand for T-shirts much. However, expectations

about prices for goods such as computers, VCRs, houses, and automobiles affect demand. For example, how would the belief that computer prices will fall 25

percent next year affect the demand today?

If any of these events occur, the demand schedule and the demand curve will change so that the quantity demanded at any particular price would be more or less than in the original demand schedule. If the demand increases, the curve shifts to the right, not "up" (Figure 3-3). If demand decreases, the curve shifts to the left, not "down."

Date: 2015-02-16; view: 1927

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Great Wall | | | Elasticity of Demand |