CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Answer the questions

1. Open the brackets and put the verbs into the Present Perfect Continuous Tense or the Present Perfect Tense.

1. I (try) to get into contact with them for a long time, but now I (give) it up as hopeless. 2. My shortsighted uncle (lose) his spectacles. We (look) for them everywhere but we canít find them. 3. She (be) of great help to us since she (live) for such a long time with us. 4. You ever (work) as in interpreter? Ė Yes, that is what I (do) for the last five months. 5. They (make up) their quarrel? Ė I donít know. I only know that they (not be) on speaking terms since September. 6. Our pilot (ask) for permission to take off for ten minutes already, but he (get) no answer yet. 7. A skilful photographer (help) me with the development of summer films for two weeks, but we (develop) only half of them. 8. I (know) them since we met at Annís party. 9. You (open) the door at last. I (ring) for an hour at least, it seems to me. 10. Look, the typist (talk) all the time, she already (miss) several words.

2. Complete the sentences with the verbs from the box using the Past Perfect Continuous Tense.

| consider burn drive hope quarrel rain practice write work try |

1. He________ the car for many hours before he came to the crossroads. 2. The pianist________ the passage hour after hour till he mastered it. 3. When I met her, her eyes were red. She and Mike again ___________. 4. When I came, they _________ this question for more than an hour. 5. It was evening and he was tired because he________ since dawn. 6. He _________ to get her on the phone for 15 minutes before he heard her voice. 7. By 12 oíclock they _________ a composition for two hours. 8. The fire __________ for some time before a fire brigade came. 9. I ________ to meet her for ages when I bumped into her by chance. 10. When I left home, it was raining, and as it ____________ since morning, the streets were muddy.

3. Choose the right variant.

1. When _____ Ann last? Ė I ______ her since she ______ to another city.

a) have you seen, havenít seen, has moved

b) did you see, didnít see, moved

c) did you see, havenít seen, moved

d) have you seen, didnít see, has moved

2. Our train _____ at 8 oíclock. If you _______ at 5, we ______ our things.

a) leaves, come, will pack

b) will leave, will come, will be packing

c) is leaving, will come, are packing

d) leaves, come, will be packing

3. They ______ to build a new McDonalds in several days and ________ it by the end of the year.

a) will start, will finish

b) are starting, will have finished

c) start, will be finishing

d) start, are finishing

4. I _______ the performance for twenty minutes when my friend ______ at last. His car _______ on his way to the theatre.

a) was watching, had come, had broken down

b) had been watching, came, had broken down

c) watched, came, broke down

d) have been watching, had come, has broken

5. look, what he ________ on the blackboard. He ________ three mistakes.

a) is writing, has made

b) has written, had made

c) has been writing, is making

d) writes, made

6. What ________ if the rain ________ by evening? It _______ since yesterday. I wonder when it _______.

a) will we do, doesnít stop, is pouring, will stop

b) are we doing, hasnít stopped, had been pouring, stops

c) shall we have done, wonít have stopped, was pouring, will be stopping

d) shall we do, hasnít stopped, has been pouring, will stop

7. What _________ when I _______? Ė We ________ the article which Mary ________ just _________. I _________ to read it for a long time.

a) did you do, was coming in, were reading, has brought, have wanted

b) were you doing, came in, were reading, had brought, had wanted

c) had you been doing, came in, read, brought, had been wanting

d) have you done, have come in, have read, has brought, wanted

8. It ________ dark, itís time for the children to go home. They ________ in the yard for the whole evening.

a) got, play

b) has got, are playing

c) is getting, have been paying

d) gets, played

9. I havenít heard you come into the room. When _______? Ė I ______ long ago. You _______ and I ________ to disturb you.

a) did you come, came, were reading, was not wanting

b) did you come, came, were reading, did not want

c) have you come, have come, have been reading, donít want

d) were you coming, was coming, read, havenít wanted

10. I _______ till Father _______. He ________ his key and I will have to wait for him.

a) wonít be leaving, will come, had lost

b) wonít leave, will come, has lost

c) wonít leave, comes, has lost

d) arenít leaving, comes, loses

TENSE

Questions for discussion:

What is tense? What is time? Which of the two is a logical concept/ a linguistic concept? In what way do these concepts correlate with each other?

How many tenses are there in the Russian language? (in the Ukrainian language? in the English language?

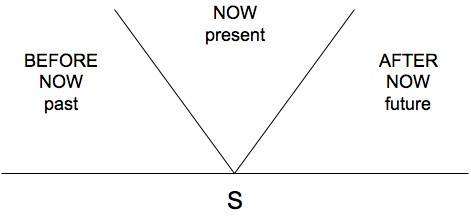

What is a ďtime lineĒ? Draw a time line.

1. Read the text.

What is 'tense'

Following Comrie (1985), we take tense to be the grammaticalisation of location in time.

Three parameters are traditionally cited as relevant in defining tense and identifying tense distinctions: (a) the location of the deictic centre (either at the present moment - in the so-called 'absolute tenses', or at a different point in time - in the so-called 'relative tenses'); (b) the location of the situation with respect to the deictic centre (i.e. prior to, subsequent to, or simultaneous with the deictic centre); and (c) the distance in time at which the situation referred to is located from the deictic centre. In the discussion of the category of tense, the term 'situation' is understood as an event, process or state, without consideration of its internal temporal contour. The internal temporal contour of the situation provides the conceptual basis for the notion of aspect.

This conceptualisation of time, which appears to be adequate for an account of tense in human language including all time location distinctions found in natural language, can be represented diagrammatically as follows:

The diagram represents time as a straight line, with the past represented conventionally to the left and the future to the right. The present moment is represented by a point on that line, labelled S (mnemonic for 'speech time'). Several things are intentionally left unspecified. One of them is whether the time line is bounded at either the left or the right, including whether it bends to form a circle. While this is an important philosophical issue, it does not seem to be relevant for the grammaticalisation of time. Similarly, conceptualisations of time as cyclic are found in all cultures, but on a macroscopic scale which does not have a bearing on tense distinctions. Furthermore, the diagram does not represent the flow of time - that is, it does not indicate whether S (or, Ego) moves along a stationary time line, or whether time flows past a stationary reference point S (or, Ego). This is another important philosophical question, but again it does not seem to play a role in the analysis of tense as a linguistic category. However, many of these culture-specific conceptualisations of time are metaphors that are important sources of time expressions across languages.

For temporal-deictic distinctions, the speech situation S projected onto the time line serves as the basic orientation point - that is, is always the primary point of reference (R0). One of the extra-linguistic presuppositions for an utterance is constituted by the speaker's consciousness of the relation of the speech situation S to the reported situation E (mnemonic for 'event') along the time line (Thelin 1978:37). A past situation is therefore located in the time before and not including the present moment, a future situation (a prediction, imposition, or an instance of pre-planning) is located in the time after the present moment, and a present situation, whether continuing or repetitive, is located in the time that includes the present moment, regardless of whether it encompasses a shorter or longer stretch of time. This concept of time, which relates a situation to the time line, is essential to the linguistic category of tense (Comrie 1985:6).

It is interesting to note that a further parameter that could theoretically be posited for tense distinctions - that of a specific location in time, or a specific time lapse - does not seem to be grammaticalised as tense. In those cultures which care about, and are able to capture, very precise location in time and very fine distinctions of time, these are usually expressed using existing grammatical patterns and the appropriate lexical items which may be combined with mathematical expressions in order to gain precision (e.g. 10.45 am on Friday, 9 June 2006; nanosecond; 10-6 seconds). On the other hand, in cultures which lack the technology to capture precise temporal locations, or attach little value to precision in temporal location, such precision may not be attainable even lexically. For example, in Yidiny, an Australian language, it is impossible to distinguish lexically between the concepts of 'today' and 'now' (Comrie 1985:7-8).

Answer the questions

1. Does your representation of ďtime lineĒ coincide with the representation described in the text?

2. What philosophically relevant aspects of time do not have a bearing on tense distinctions?

3. What are the three parameters thought to be relevant in identifying tense distinctions?

4. Which of the three parameters is not grammaticalised as tense?

5. In what way is this parameter (not grammaticalised as tense) expressed in languages? Do these linguistic means of expression depend on culture?

6. Does the description of speech situations refer to logical conceptualization or linguistic expression? Prove your point.

3. Choose the correct variant.

1. ďTemporalĒ is the corresponding adjective for

- time +

- tense

- tempo

2. The present moment is

- a short stretch of time (only the moment when the speaker pronounces the utterance)

- a shorter or longer stretch of time +

- a period of time when the utterance holds true

3. The difference between ďabsoluteĒ and ďrelativeĒ tenses lies in

- the speakerís attitude to the situation (whether they see the situation as real or unreal)

- the location of the deictic center (whether the deictic center is located at the present moment or at a different point in time) +

- the location of the situation with respect to the deictic center (whether the situation is prior to, subsequent to, or simultaneous with the deictic center)

4. The time line is conventionally represented as

- curvy

- going upwards

- straight +

Expressions of 'tense'

Location in time can be achieved linguistically in many different ways ranging from purely lexical to grammatical. Comrie (1985:8-9) suggests grouping them in three classes:

Lexically composite expressions - these involve slotting time specifications into the positions of a syntactic expression, e.g. the English five minutes after John left, 10-45 seconds after the Big Bang, the day before yesterday, last year. This set is potentially infinite in a language that has linguistic means for measuring time intervals.

Lexical items - these include items such as: the English now, today, yesterday; the Czech loni 'last year'. The range of time distinctions captured through single lexical items is necessarily smaller than that which is possible using lexically composite expressions, as it depends on the stock of items listed in the lexicon in the given language.

Grammatical categories - this is the set of grammaticalised expressions of location in time, that is the set of tenses in the given language. This set is the smallest of the three, with a finite number of synchronically listed items (tense values), and it is possible that for some languages it may contain no items, as there may be languages with no grammatical category of tense.

In order to be regarded as a (grammaticalised) tense, the expression of location in time has to be integrated into the grammatical system of the language. In contrast, a lexicalised expression of the location in time indicates its integration into the lexicon of the language, but does not entail any necessary consequences for the language's grammatical structure. Grammaticalisation, as opposed to lexicalisation, of the location in time, correlates with two parameters: obligatory expression and morphological boundness. The very rough rule is that a tense is grammaticalised if its morphological expression is obligatory even if the information carried by the exponent is redundant. For example, in the English sentence Last year I bought a new car "the choice of a tense other than the simple past would make the sentence anomalous, although the information that the event took place in the past is expressed unambiguously by last year" (Dahl & Velupillai 2005:266). The obligatoriness of tense can also be demonstrated in languages which allow for tense marking to be omitted in some circumstances. This has been argued for Central Alaskan Yup'ik whose tense system is relative (the deictic centre can shift even within one sentence between the time of speech and another reference point) and where the absence of an overt tense suffix has to be recognised as a meaningful zero (Mithun 1999). Morphological boundness is perhaps a slightly more problematic criterion, which is not necessary in itself - as in Yemba (Niger-Congo), where tense is expressed primarily by means of auxiliaries (i.e. not bound morphemes) which are also clearly not separate lexical items which could be seen as contributing to the compositional meaning of tense (Comrie 1985:11).

Tense is typically a morphological category of the verb, or verbal complex, and it can be expressed either by verbal inflection (on the main verb or the auxiliary - as in English), or by grammatical words adjacent (ÍÓÚÓūŻŚ ÔūŤžŻÍŗĢÚ) to the verb (such as the Yemba tense auxiliaries; see above). It can also be analysed as a grammatical category of the clause. Anderson (1992) classifies tense as 'phrasal inflection' (distinct from 'configurational inflection' such as case, 'agreement inflection' such as number concord on English verbs, or 'inherent inflection' such as gender on Latin nouns), because it is a property that is "assigned to a larger constituent within a structure" (a clause) but "realized on individual words" (verbs). Similarly, Booij (1994:30) argues that tense has scope over a whole clause (however, he classifies it as 'inherent inflection', opposed to 'contextual', because "the tense of the verb is not determined by syntactic structure". It is, therefore, not unexpected that tense can also be expressed by a marker placed in the position of sentence particles (as in the sentence-second position in Warlpiri, Australian; Hale 1973, cited in Comrie 1985:12), that languages may allow multiple marking of the tense value on different elements in the same clause or that tense systematically does not occur on non-finite verb forms.

Finally, it is important to note that there is often no agreement between scholars about the classification of individual grammatical forms, especially when the verbal forms and constructions simultaneously involve semantic elements from different domains, typically those of aspect and mood (see Dahl 1985), but also case (e.g. in Australian languages - see Evans 1995; 2003) and other categories. In fact, there are seldom grammatical markers that express just the temporal location of the situation.

Date: 2014-12-22; view: 2174

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| GRAMMAR PRACTICE | | | Information Systems General Coordination. Culture and Entertainment Web |