CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Our Brains Control Our Thoughts, Feelings, and Behavior

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. Describe the structures and function of the “old brain” and its influence on behavior.

2. Explain the structure of the cerebral cortex (its hemispheres and lobes) and the function of each area of the cortex.

3. Define the concepts of brain plasticity, neurogenesis, and brain lateralization.

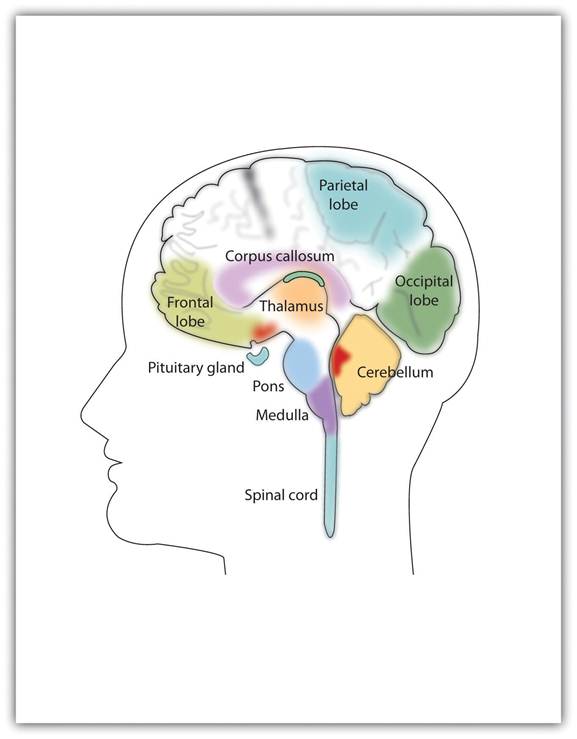

If you were someone who understood brain anatomy and were to look at the brain of an animal that you had never seen before, you would nevertheless be able to deduce the likely capacities of the animal. This is because the brains of all animals are very similar in overall form. In each animal the brain is layered, and the basic structures of the brain are similar (see Figure 3.6 "The Major Structures in the Human Brain"). The innermost structures of the brain—the parts nearest the spinal cord—are the oldest part of the brain, and these areas carry out the same the functions they did for our distant ancestors. The “old brain” regulates basic survival functions, such as breathing, moving, resting, and feeding, and creates our experiences of emotion. Mammals, including humans, have developed further brain layers that provide more advanced functions—for instance, better memory, more sophisticated social interactions, and the ability to experience emotions. Humans have a very large and highly developed outer layer known as the cerebral cortex (see Figure 3.7 "Cerebral Cortex"), which makes us particularly adept at these processes.

Figure 3.6 The Major Structures in the Human Brain

The major brain parts are colored and labeled.

Source: Adapted from Camazine, S. (n.d.). Images of the brain. Medical, science, and nature things: Photography and digital imagery by Scott Camazine. Retrieved from http://www.scottcamazine.com/photos/brain/pages/09MRIBrain_jpg.htm.

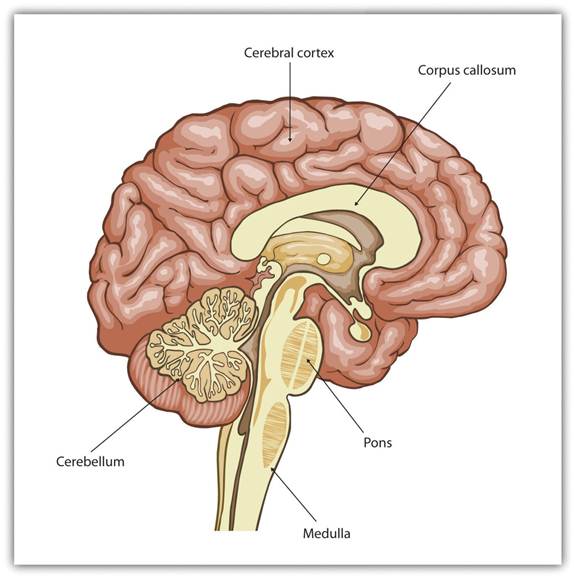

Figure 3.7 Cerebral Cortex

Humans have a very large and highly developed outer brain layer known as the cerebral cortex. The cortex provides humans with excellent memory, outstanding cognitive skills, and the ability to experience complex emotions.

Source: Adapted from Wikia Education. (n.d.). Cerebral cortex. Retrieved fromhttp://psychology.wikia.com/wiki/Cerebral_cortex.

The Old Brain: Wired for Survival

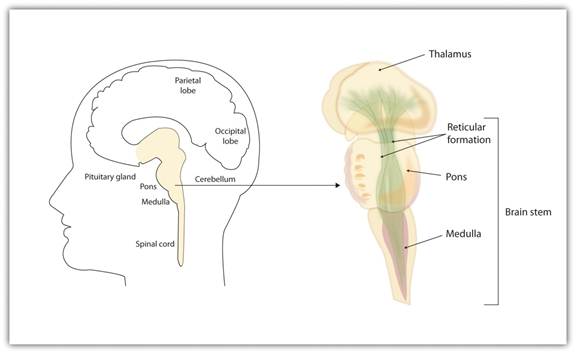

The brain stem is the oldest and innermost region of the brain. It’s designed to control the most basic functions of life, including breathing, attention, and motor responses (Figure 3.8 "The Brain Stem and the Thalamus"). The brain stem begins where the spinal cord enters the skull and forms the medulla, the area of the brain stem that controls heart rate and breathing. In many cases the medulla alone is sufficient to maintain life—animals that have the remainder of their brains above the medulla severed are still able to eat, breathe, and even move. The spherical shape above the medulla is the pons, a structure in the brain stem that helps control the movements of the body, playing a particularly important role in balance and walking.

Running through the medulla and the pons is a long, narrow network of neurons known as the reticular formation. The job of the reticular formation is to filter out some of the stimuli that are coming into the brain from the spinal cord and to relay the remainder of the signals to other areas of the brain. The reticular formation also plays important roles in walking, eating, sexual activity, and sleeping. When electrical stimulation is applied to the reticular formation of an animal, it immediately becomes fully awake, and when the reticular formation is severed from the higher brain regions, the animal falls into a deep coma.

Figure 3.8 The Brain Stem and the Thalamus

The brain stem is an extension of the spinal cord, including the medulla, the pons, the thalamus, and the reticular formation.

Above the brain stem are other parts of the old brain that also are involved in the processing of behavior and emotions (see Figure 3.9 "The Limbic System"). The thalamus is the egg-shaped structure above the brain stem that applies still more filtering to the sensory information that is coming up from the spinal cord and through the reticular formation, and it relays some of these remaining signals to the higher brain levels (Guillery & Sherman, 2002). [1] The thalamus also receives some of the higher brain’s replies, forwarding them to the medulla and the cerebellum. The thalamus is also important in sleep because it shuts off incoming signals from the senses, allowing us to rest.

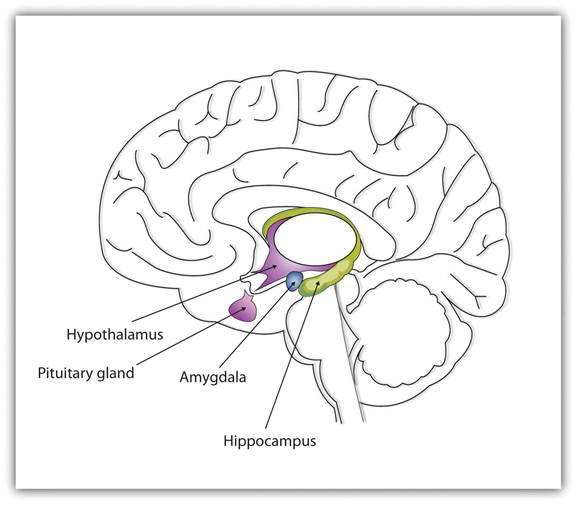

Figure 3.9 The Limbic System

This diagram shows the major parts of the limbic system, as well as the pituitary gland, which is controlled by it.

The cerebellum (literally, “little brain”) consists of two wrinkled ovals behind the brain stem. It functions to coordinate voluntary movement.

People who have damage to the cerebellum have difficulty walking, keeping their balance, and holding their hands steady. Consuming alcohol influences the cerebellum, which is why people who are drunk have more difficulty walking in a straight line. Also, the cerebellum contributes to emotional responses, helps us discriminate between different sounds and textures, and is important in learning (Bower & Parsons, 2003). [2]

Whereas the primary function of the brain stem is to regulate the most basic aspects of life, including motor functions, the limbic system is largely responsible for memory and emotions, including our responses to reward and punishment. The limbic system is a brain area, located between the brain stem and the two cerebral hemispheres, that governs emotion and memory. It includes the amygdala, the hypothalamus, and the hippocampus.

The amygdala consists of two “almond-shaped” clusters (amygdala comes from the Latin word for “almond”) and is primarily responsible for regulating our perceptions of, and reactions to, aggression and fear. The amygdala has connections to other bodily systems related to fear, including the sympathetic nervous system (which we will see later is important in fear responses), facial responses (which perceive and express emotions), the processing of smells, and the release of neurotransmitters related to stress and aggression (Best, 2009).[3] In one early study, Klüver and Bucy (1939) [4] damaged the amygdala of an aggressive rhesus monkey. They found that the once angry animal immediately became passive and no longer responded to fearful situations with aggressive behavior. Electrical stimulation of the amygdala in other animals also influences aggression. In addition to helping us experience fear, the amygdala also helps us learn from situations that create fear. When we experience events that are dangerous, the amygdala stimulates the brain to remember the details of the situation so that we learn to avoid it in the future (Sigurdsson, Doyère, Cain, & LeDoux, 2007). [5]

Located just under the thalamus (hence its name) the hypothalamus is a brain structure that contains a number of small areas that perform a variety of functions, including the important role of linking the nervous system to the endocrine system via the pituitary gland. Through its many interactions with other parts of the brain, the hypothalamus helps regulate body temperature, hunger, thirst, and sex, and responds to the satisfaction of these needs by creating feelings of pleasure. Olds and Milner (1954) [6] discovered these reward centers accidentally after they had momentarily stimulated the hypothalamus of a rat. The researchers noticed that after being stimulated, the rat continued to move to the exact spot in its cage where the stimulation had occurred, as if it were trying to re-create the circumstances surrounding its original experience. Upon further research into these reward centers, Olds (1958) [7] discovered that animals would do almost anything to re-create enjoyable stimulation, including crossing a painful electrified grid to receive it. In one experiment a rat was given the opportunity to electrically stimulate its own hypothalamus by pressing a pedal. The rat enjoyed the experience so much that it pressed the pedal more than 7,000 times per hour until it collapsed from sheer exhaustion.

The hippocampus consists of two “horns” that curve back from the amygdala. The hippocampus is important in storing information in long-term memory. If the hippocampus is damaged, a person cannot build new memories, living instead in a strange world where everything he or she experiences just fades away, even while older memories from the time before the damage are untouched.

The Cerebral Cortex Creates Consciousness and Thinking

All animals have adapted to their environments by developing abilities that help them survive. Some animals have hard shells, others run extremely fast, and some have acute hearing. Human beings do not have any of these particular characteristics, but we do have one big advantage over other animals—we are very, very smart.

You might think that we should be able to determine the intelligence of an animal by looking at the ratio of the animal’s brain weight to the weight of its entire body. But this does not really work. The elephant’s brain is one thousandth of its weight, but the whale’s brain is only one ten-thousandth of its body weight. On the other hand, although the human brain is one 60th of its body weight, the mouse’s brain represents one fortieth of its body weight. Despite these comparisons, elephants do not seem 10 times smarter than whales, and humans definitely seem smarter than mice.

The key to the advanced intelligence of humans is not found in the size of our brains. What sets humans apart from other animals is our larger cerebral cortex—the outer bark-like layer of our brain that allows us to so successfully use language, acquire complex skills, create tools, and live in social groups (Gibson, 2002). [8] In humans, the cerebral cortex is wrinkled and folded, rather than smooth as it is in most other animals. This creates a much greater surface area and size, and allows increased capacities for learning, remembering, and thinking. The folding of the cerebral cortex is referred to as corticalization.

Although the cortex is only about one tenth of an inch thick, it makes up more than 80% of the brain’s weight. The cortex contains about 20 billion nerve cells and 300 trillion synaptic connections (de Courten-Myers, 1999). [9] Supporting all these neurons are billions more glial cells (glia), cells that surround and link to the neurons, protecting them, providing them with nutrients, and absorbing unused neurotransmitters. The glia come in different forms and have different functions. For instance, the myelin sheath surrounding the axon of many neurons is a type of glial cell. The glia are essential partners of neurons, without which the neurons could not survive or function (Miller, 2005). [10]

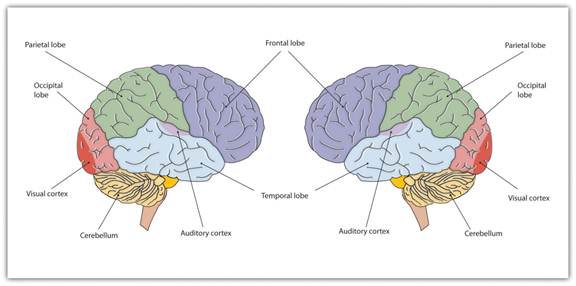

The cerebral cortex is divided into two hemispheres, and each hemisphere is divided into four lobes, each separated by folds known as fissures. If we look at the cortex starting at the front of the brain and moving over the top (see Figure 3.10 "The Two Hemispheres"), we see first the frontal lobe (behind the forehead), which is responsible primarily for thinking, planning, memory, and judgment. Following the frontal lobe is the parietal lobe, which extends from the middle to the back of the skull and which is responsible primarily for processing information about touch. Then comes the occipital lobe, at the very back of the skull, which processes visual information. Finally, in front of the occipital lobe (pretty much between the ears) is the temporal lobe, responsible primarily for hearing and language.

Figure 3.10 The Two Hemispheres

The brain is divided into two hemispheres (left and right), each of which has four lobes (temporal, frontal, occipital, and parietal). Furthermore, there are specific cortical areas that control different processes.

Date: 2015-01-29; view: 1653

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| The Neuron Is the Building Block of the Nervous System | | | Functions of the Cortex |