CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Levels of Explanation in Psychology

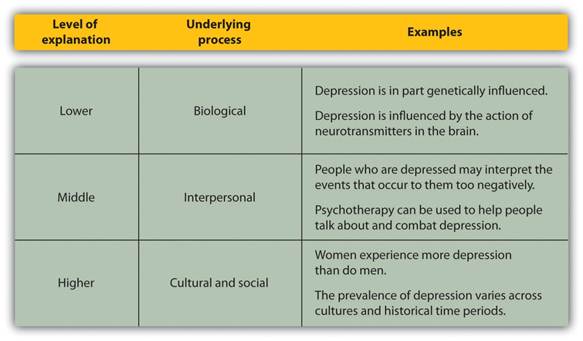

The study of psychology spans many different topics at many different levels of explanation, which are the perspectives that are used to understand behavior. Lower levels of explanation are more closely tied to biological influences, such as genes, neurons, neurotransmitters, and hormones, whereas the middle levels of explanation refer to the abilities and characteristics of individual people, and the highest levels of explanation relate to social groups, organizations, and cultures (Cacioppo, Berntson, Sheridan, & McClintock, 2000). [7]

The same topic can be studied within psychology at different levels of explanation, as shown in Figure 1.3 "Levels of Explanation". For instance, the psychological disorder known as depression affects millions of people worldwide and is known to be caused by biological, social, and cultural factors. Studying and helping alleviate depression can be accomplished at low levels of explanation by investigating how chemicals in the brain influence the experience of depression. This approach has allowed psychologists to develop and prescribe drugs, such as Prozac, which may decrease depression in many individuals (Williams, Simpson, Simpson, & Nahas, 2009). [8] At the middle levels of explanation, psychological therapy is directed at helping individuals cope with negative life experiences that may cause depression. And at the highest level, psychologists study differences in the prevalence of depression between men and women and across cultures. The occurrence of psychological disorders, including depression, is substantially higher for women than for men, and it is also higher in Western cultures, such as in the United States, Canada, and Europe, than in Eastern cultures, such as in India, China, and Japan (Chen, Wang, Poland, & Lin, 2009; Seedat et al., 2009). [9] These sex and cultural differences provide insight into the factors that cause depression. The study of depression in psychology helps remind us that no one level of explanation can explain everything. All levels of explanation, from biological to personal to cultural, are essential for a better understanding of human behavior.

Figure 1.3 Levels of Explanation

The Challenges of Studying Psychology

Understanding and attempting to alleviate the costs of psychological disorders such as depression is not easy, because psychological experiences are extremely complex. The questions psychologists pose are as difficult as those posed by doctors, biologists, chemists, physicists, and other scientists, if not more so (Wilson, 1998). [10]

A major goal of psychology is to predict behavior by understanding its causes. Making predictions is difficult in part because people vary and respond differently in different situations. Individual differences are the variations among people on physical or psychological dimensions. For instance, although many people experience at least some symptoms of depression at some times in their lives, the experience varies dramatically among people. Some people experience major negative events, such as severe physical injuries or the loss of significant others, without experiencing much depression, whereas other people experience severe depression for no apparent reason. Other important individual differences that we will discuss in the chapters to come include differences in extraversion, intelligence, self-esteem, anxiety, aggression, and conformity.

Because of the many individual difference variables that influence behavior, we cannot always predict who will become aggressive or who will perform best in graduate school or on the job. The predictions made by psychologists (and most other scientists) are only probabilistic. We can say, for instance, that people who score higher on an intelligence test will, on average, do better than people who score lower on the same test, but we cannot make very accurate predictions about exactly how any one person will perform.

Another reason that it is difficult to predict behavior is that almost all behavior is multiply determined, or produced by many factors. And these factors occur at different levels of explanation. We have seen, for instance, that depression is caused by lower-level genetic factors, by medium-level personal factors, and by higher-level social and cultural factors. You should always be skeptical about people who attempt to explain important human behaviors, such as violence, child abuse, poverty, anxiety, or depression, in terms of a single cause.

Furthermore, these multiple causes are not independent of one another; they are associated such that when one cause is present other causes tend to be present as well. This overlap makes it difficult to pinpoint which cause or causes are operating. For instance, some people may be depressed because of biological imbalances in neurotransmitters in their brain. The resulting depression may lead them to act more negatively toward other people around them, which then leads those other people to respond more negatively to them, which then increases their depression. As a result, the biological determinants of depression become intertwined with the social responses of other people, making it difficult to disentangle the effects of each cause.

Another difficulty in studying psychology is that much human behavior is caused by factors that are outside our conscious awareness, making it impossible for us, as individuals, to really understand them. The role of unconscious processes was emphasized in the theorizing of the Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), who argued that many psychological disorders were caused by memories that we have repressed and thus remain outside our consciousness. Unconscious processes will be an important part of our study of psychology, and we will see that current research has supported many of Freud’s ideas about the importance of the unconscious in guiding behavior.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

· Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior.

· Though it is easy to think that everyday situations have commonsense answers, scientific studies have found that people are not always as good at predicting outcomes as they think they are.

· The hindsight bias leads us to think that we could have predicted events that we actually could not have predicted.

· People are frequently unaware of the causes of their own behaviors.

· Psychologists use the scientific method to collect, analyze, and interpret evidence.

· Employing the scientific method allows the scientist to collect empirical data objectively, which adds to the accumulation of scientific knowledge.

· Psychological phenomena are complex, and making predictions about them is difficult because of individual differences and because they are multiply determined at different levels of explanation.

EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

1. Can you think of a time when you used your intuition to analyze an outcome, only to be surprised later to find that your explanation was completely incorrect? Did this surprise help you understand how intuition may sometimes lead us astray?

2. Describe the scientific method in a way that someone who knows nothing about science could understand it.

3. Consider a behavior that you find to be important and think about its potential causes at different levels of explanation. How do you think psychologists would study this behavior?

[1] Nisbett, R. E., & Ross, L. (1980). Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

[2] Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; Kelley, H. H. (1967). Attribution theory in social psychology. In D. Levine (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 15, pp. 192–240). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

[3] Cutler, B. L., & Wells, G. L. (2009). Expert testimony regarding eyewitness identification. In J. L. Skeem, S. O. Lilienfeld, & K. S. Douglas (Eds.), Psychological science in the courtroom: Consensus and controversy (pp. 100–123). New York, NY: Guilford Press; Wells, G. L., & Hasel, L. E. (2008). Eyewitness identification: Issues in common knowledge and generalization. In E. Borgida & S. T. Fiske (Eds.), Beyond common sense: Psychological science in the courtroom (pp. 159–176). Malden, NJ: Blackwell.

[4] Gilovich, T. (1993). How we know what isn’t so: The fallibility of human reason in everyday life. New York, NY: Free Press.

[5] Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (2007). Social cognition: From brains to culture. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.; Hsee, C. K., & Hastie, R. (2006). Decision and experience: Why don’t we choose what makes us happy? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(1), 31–37.

[6] Brendl, C. M., Chattopadhyay, A., Pelham, B. W., & Carvallo, M. (2005). Name letter branding: Valence transfers when product specific needs are active. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(3), 405–415.

[7] Cacioppo, J. T., Berntson, G. G., Sheridan, J. F., & McClintock, M. K. (2000). Multilevel integrative analyses of human behavior: Social neuroscience and the complementing nature of social and biological approaches. Psychological Bulletin, 126(6), 829–843.

[8] Williams, N., Simpson, A. N., Simpson, K., & Nahas, Z. (2009). Relapse rates with long-term antidepressant drug therapy: A meta-analysis. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 24(5), 401–408.

[9] Chen, P.-Y., Wang, S.-C., Poland, R. E., & Lin, K.-M. (2009). Biological variations in depression and anxiety between East and West. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 15(3), 283–294; Seedat, S., Scott, K. M., Angermeyer, M. C., Berglund, P., Bromet, E. J., Brugha, T. S.,…Kessler, R. C. (2009). Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(7), 785–795.

[10] Wilson, E. O. (1998). Consilience: The unity of knowledge. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Date: 2015-01-29; view: 10995

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Research Focus: Unconscious Preferences for the Letters of Our Own Name | | | The Evolution of Psychology: History, Approaches, and Questions |