CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Demand conditions

100% of processed marble is sold and consumed in the domestic market for local

construction. The nature of demand inside the country is not so complicated. The

finished products are organized around tiles for construction in different sizes. Size is an important factor in tiles. Unless consumers order for an unusual size, the standard sizes for tiles in the Afghan domestic market are limited to the followings:

a) Square tile: 30 cm x 30 cm x 1 cm and 30 cm x 30 cm x 2 cm;

b) Rectangular tile: 15 cm x 60 cm x 1 cm and 15 cm x 30 cm x 1 cm;

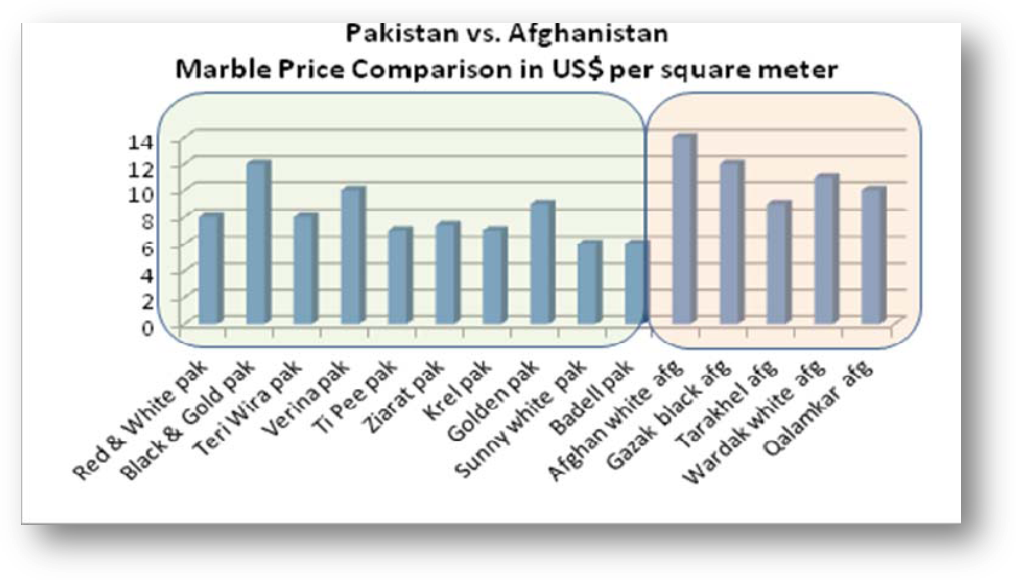

c) Rectangular tile big size: 30 cm x 120 cm x 2 cm and 60 cm x 120 cm to 250 cm x 2cm. The problem is that not all of the volume that is quarried is processed in the country. A big portion of quarried marble is shipped to the neighbor country, Pakistan for processing purposes; much of this shipping happens illegally. These are often re-imported as higher value-added polished marble product (Mitchell, 2008). The fact that continuous shipments of unprocessed marble to Pakistan is happening and many European and other foreign buyers are asking for Afghan marble indicate a strong export potential. However, what is processed by the domestic processors, are not acceptable for the international buyers in terms of quality of the finished products. This partially explains that the nature of foreign markets for marble seems to be more complicated than the domestic market. Afghan processors cannot meet the standards of foreign markets in terms of quality that comes out of value adding activities such as polishing and finishing. The reason for low quality finished goods/products is influenced by several factors such as lack of technical knowledge, lack of standard and modern equipments and the machineries, lack of energy resources, etc. The other important challenge in demand conditions that exists, is lack of understanding of the requirements of the international buyers. What helps the Afghan producers in this area is to know marketing techniques in one hand and on the other, be equipped with up to date knowledge about the world markets and the nature of their demand and continue to meet those demands/standards. Context of firm strategy, structure and rivalry: In terms of legislation, the minerals law of Afghanistan exists that governs the “the ownership, control, prospecting, exploration, exploitation, extraction, concentration, processing, transformation, transportation, marketing, sale and export of mineral substances in the territory of Afghanistan” (Minerals Law of Afghanistan, 2005). The law supports development of mineral activities “through or in association with the private sector,” which provides the opportunity for the marble private companies to invest in the industry. Based on this law, clear procedures exist that outlines the duties and responsibilities of the Ministry of Mines and Minerals in regard to the minerals including marble. In addition to the Minerals Law, there exists the “Partnership Law of Afghanistan” that facilitates and “regulates the affairs related to activities and creation of Partnerships” between the private sector and the government of Afghanistan. Literally there is a will to develop the sector through the private sector, but actually when it comes to the real world, the practices are not that promising. First of all, the ministry’s capacity is limited in terms of initiating policies, strategies and tactics that could further facilitate and enforce development of the sector as well as the cluster. Expertise at the ministry is very focused around the geological aspect of the minerals rather than the business side of it. Most of the personnel at the ministry consist of geology engineers at all levels, e.g., the minister, his deputy, directors of major departments are all geologists whose knowledge remain limited to the technical geological aspects of the minerals. They rarely think about the economy and business part of these god-given gifts in which the nation has comparative advantage. There is a big gap to be filled by new policies and new strategies/tactics that could practically enforce development of businesses, foreign and domestic direct investments in the cluster. E.g., the ministry could initiate penetration pricing policy for couple of years in order to attract investment in the cluster. Currently the Ministry’s pricing policy is in no way competitive in compare with the neighboring countries especially Pakistan. for comparison of the prices of tiles for Afghan marble versus Pakistan, the neighboring country. Looking at the graph, Pakistan marble prices are more competitive against the Afghan marble in terms of price; value added quality, and diversification in types despite the transportation cost for import. In comparison, the Afghan marble is less competitive in terms of price; value added quality; and diversification in type despite being produced within the country and without extra transportation charges. Based on interviews with the marble processing companies, a big portion of the cost—through the value chain—is going to the royalty fee imposed by the Ministry of Mines and Industries, which increases the cost of production. Other factors also play a major role such as lack of power and production efficiency as a result of modern equipments and technology. The Ministry’s knowledge about the marble market and the prices remains very little and insufficient i.e. when the deputy Minster was asked about the prices of marble in the neighboring countries and how his ministry was acting in terms of competitiveness; the answer was simply “I don’t know.” In summary, the ministry is not thinking economically and competitively about the natural resources that it holds, which by itself is a major barrier against development of the sector as well as the cluster.

In addition to the low capacity, lack of knowledge in management and competitiveness, there exist a kind of negative attitude and mentality amongst employees of the government at different levels against the private sector. For example, they don’t seem to be enthusiastically cooperative and helpful with the private sector companies as well as other customers e.g. when the author of this paper was dealing with them to collect the relevant data at some departments of the Ministry of Mines, this was very obvious in several occasions. This negative attitude seems to be the most dangerous phenomenon for development of the sector. To overcome this challenge a lot of awareness building and capacity development activities need to be initiated and sustainably followed in the medium and long term. In terms of technical capacity personnel of the Ministry looks to have geological knowledge, but lack the capacity – in terms of finances – to conduct the required surveys and feasibility studies for the benefit of the private sector investments. The Ministry has put in place standard provisions for contracting the quarrying operations of marble to the private companies. However, some of the provisions don’t seem to be realistic given the current capacity of the private sector in the country as well as the overall context for business development. Please see Exhibit number three for the translated copy of the standard provisions. Marble companies have problems with several articles such as article number 5, 6, 7, and 9. The rate of royalty fee in Article 5 comes out of the initial price set by the Ministry based on one of the categories in the Table presented at the Exhibit four and a subsequent bidding process, which imposes high royalty fee over the companies on marble extraction in compare with the neighboring countries. Other challenges as a result of the standard provisions are advance payment, mandatory volume of marble to be quarried in each year without consideration of seasonal barriers as a result of weather and week infrastructure such as muddy roads that gets blocked easily in rainy seasons. On top of these, expenses of the geological engineer such as purdiam, transportation cost, and other privileges linked to the regular travels for the purpose of monitoring fall over the shoulders of the contracting company doing the quarrying operation.

The business community for marble production is 100% comprised of domestic companies. Foreign Investment has not taken place yet. Much of knowledge of the domestic companies is focused on production and the relevant approaches. “Little capacity exists in the business community for business plan writing,” etc. (the OTF group,2006). “Credit is difficult to access and expensive.” One in fond of access to credit must be equipped with modern business knowledge of proposal writing, budget planning, business plan writing, etc, which is lacking amongst the business community for marble production in Afghanistan. Rivalry remains limited to the domestic companies although the size of the afghan marble industry is not well known the association of marbles and Granite processor of Afghanistan AMGPA indicated that there are around 130 factories producing ,marbles across the country most of these company are small scale producing the overall context for rivalry is not impressive and therefore, the growth of companies has been going through a declining trend. Based on information provided by Mr. Besmella Ebrahimi – Director General for Khaled Omid Marble company and a key member of the Afghanistan Marble and Granite Processors Association (AMGPA) – 65% of companies that were established with the mandate to work in marble industry have not been productive at all. 14% of companies could only continue to produce till early 2008 and went bankrupt afterwards. Only 16% of companies are functioning at the moment and can continue to produce. Five percent of companies are involved in quarrying operations only. The pie chart shows that clearly: For the purpose of analyzing the productivity of the cluster, the author selected top four leading companies out of 16 that are currently functioning and producing marble tiles. The aggregate amount of production for the four companies seems to be impressive till 2005 and not so well afterwards. The affecting factors for the decline in the production trend generally are those identified in the diamond for the cluster. But the problem mainly stems from the inappropriate context that cannot facilitate healthy and proper development of the cluster.

In general, 2008 has not been a productive year for the cluster at all. Even the top performing company that could maintain a gradual growth rate throughout the years failed in 2008 to meet its previous year level of production.

Related and supporting industries and institutes:

Afghanistan’s Marble and Granite Processors Association (AMGPA) as a supporting

association was created in 2006 by the Afghan marble companies to carry out lobbying and advocacy activities for the benefit of the marble industry in Afghanistan (AMGPA quarterly, 2007). The Association has taken some initiatives to establish relationship with donors, buyers and other supporting agencies on the ground and in the region. As an example, “the efforts of marble promotional events such as ‘the big five’ exhibition and the Afghan Marble Showcase, both held in Dubai in 2007” (Mitchell, 2008) can be noted down as few of the successes for the Association. However, “the Association does not have cohesive focus on the industry” (the OTF Group, 2006). Based on interviews with members of the Association, the Author found out that there is not adequate transparency in terms of procedures and official relationship in place for the members of the Association. This results very “little knowledge sharing between the cluster members” (the OTF Group, 2006). This little knowledge and information sharing has been declining trust among the members. A major challenge is financial support. The companies are small scale and therefore, lack capital cost to buy modern quarrying and processing equipments. Supporting financial institutions e.g. banks provide loans with high interest rates that is not affordable by the marble processors. “Overall, financial sector constrains development with limited

investment and working capital. Few donors are looking at marble industry” (the OTF Group, 2006) and so far none has really taken practical step into some kind of investment in the marble cluster. “Lack of proper equipment and knowledge leads to extraction methods that ruin the value of the marble.” Afghanistan Small and Medium Enterprises Development (ASMED) is a program financed by USAID, which provides some minor support to the marble companies. E.g., they have facilitated arrangement of couple of marble exhibition shows in the region such as the “big 5 event” in Dubai in 2007. Institutional support from the relevant ministries is very poor. In addition to lack of surveying capabilities there exist “murky procedures for quarrying rights, land titling issues, etc.” (the OTF Group, 2006). Manufacturing companies for equipments and machineries do not exist in country and therefore, all these has to be imported from outside mainly China and Pakistan.

| CONTEXT OF FIRM STRATEGY, STRUCTURE AND RIVALRY: • Legislatively minerals law of Afghanistan exists to govern marble quarrying and processing. • Partnership law exists to facilitate FDI and DDI. • MMI capacity is limited to initiate policies and strategies to create a better environment for marble business. • MMI leadership does not think like an economist rather thinks like a geologist. • Ministry pricing policy for quarrying is uncompetitive. • Negative attitude of government employees. • MMI’s standard provisions for quarrying is not realistic. • Business community lack marketing and business planning knowledge. • Rivalry is limited to domestic companies. |

| FACTOR CONDITIONS: • Afghan marble is of best quality and huge quantity. • Strategic location geographically accessible to Middle East and central Asian markets. • Some Afghan returnees from Iran are skilled in marble processing. • Infrastructure i.e. roads, power plants, systems, and procedures in place is very week and almost inexistent. • Security profile is poor in certain parts of the country and good in other areas. |

| DEMAND CONDITIONS: • 100% of processed marble is liquidated in country. • Less sophisticated nature of domestic demand (only some standard sizes). • Not all of the quarried marble is processed in country. Some goes to Pakistan. • Quality of finished marble products are low and not meeting the international demand. • Marble producers lack understanding of the requirements of international buyers. |

| RELATED AND SUPPORTING INDUSTRIES & INSTITUTES: • AMGPA Association as a support agency exist that lobbies and advocates for the cluster. • Information sharing lacks amongst the members of the cluster. • Loans are available with high interest rates. • Institutional support from relevant ministries is poor. • Manufacturing companies for equipments and machineries don’t exist in country. • ASMED provides some minor supports to the marble companies through the AMGPA. Marketing exhibitions is an example of the kind of support they provide to the cluster members. |

Cluster Diamond Advantages and Disadvantages:

Based on the above discussion, the advantages and disadvantages under each of the four attributes in the cluster diamond can be noted as follows:

Factor Conditions Advantages:

• Afghanistan marble is of best quality and is available in huge quantities that can supply the regional as well as the Europe and U.S. markets.

• Afghanistan has a strategic location that is geographically accessible to Middle East and central Asian markets.

• Some Afghan returnees from Iran are skilled in marble processing techniques.

Factor Conditions Disadvantages:

• Infrastructure i.e., roads, power plants, systems, and procedures in place are very week and almost inexistent.

• Security profile is poor in certain parts of the country, especially at the quarry sites.

Demand Conditions Advantages:

• There is high demand for marble in the domestic market. Currently 100% of

processed marble is liquidated in country.

• The nature of demand in the domestic market is less sophisticated at the moment,

which does not give a hard time for the processing companies in production. This can be an advantage especially at this time since the marble companies are not well

developed yet.

Demand Conditions Disadvantages:

• Not all of the quarried marble is processed within the country. Unknown quantities

are illegally quarried and exported to Pakistan for processing.

• Lack of sophisticated nature of domestic demand would cause less initiative and

competition amongst the marble processing companies.

• Quality of finished marble products are low and not meeting the international demand standards.

• Marble producers lack understanding of the requirements of international buyers.

Related and Supporting Industries Advantages:

· AMGPA as a support association exist that lobbies and advocates for the cluster.

· ASMED provides some minor supports to the marble companies through the

· AMGPA. Marketing exhibitions is an example of the kind of support they provide to the cluster members.

Related and Supporting Industries Disadvantages:

• Information sharing lacks amongst the members of the cluster.

• Banks are available that provide loans but with high interest rates.

• Institutional support from relevant ministries is poor. Ministry of Mines and

Industries does not take initiatives – even at the strategy and policy level to further

develop the industry and the cluster.

• Afghanistan lacks manufacturing companies for equipments and machineries for

marble processing factories.

Context for Firm Strategy, Structure and Rivalry Advantages:

• Legislatively minerals law of Afghanistan exists to govern marble quarrying and

processing. Partnership law exists to facilitate FDI and DDI.

• Easy and simple process for registering companies in the real world.

Context for Firm Strategy, Structure and Rivalry Disadvantages:

• MMI capacity is limited to initiate polices and strategies to create a better

environment for marble business.

• MMI leadership does not think like an economist rather they think like geologists.

• Ministry pricing policy for quarrying is uncompetitive.

• Government employees have some kind of negative attitude that creates a big obstacle against development of the sector.

• MMI’s standard provisions for quarrying contracts is not realistic.

• Business community for marble lack marketing and business planning knowledge and skills.

• Rivalry is limited to domestic companies only.

The Five Forces of Porter influencing the Afghan Marble Cluster:

Different industries can sustain different levels of profitability; part of this difference is explained by the industry structure (Quick MBA, 2007). Michael Porter provided a framework that models an industry as being influenced by five forces (such as bargaining power of suppliers, bargaining power of customers, threat of entrants, threat of substitute products or services). “The collective strength of these forces determines the ultimate profit potential of an industry” (Porter, 1998). Porter says, “the weaker the forces collectively; however, the grater the opportunity for superior performance.” Porter studies the relationship of the forces with the concerned companies in an industry. Whatever their collective strength, the corporate strategist’s goal is to find apposition in the industry where his or her company can best defend itself against these forces or can influence them in its favor. The collective strength of the forces may be painfully apparent to all the antagonists; but to cope with them, the strategist must delve below the surface and analyze the sources of each. For example, what makes the industry vulnerable to entry? What determines the bargaining power of suppliers? (Porter, 1998) For the purpose of this paper, to analyze the marble cluster, it is essential to “delve below the surface” and study each of the forces in greater possible details to find out how they

influence the marble cluster in Afghanistan:

Threat of new entrants: “new entrants to an industry bring new capacity, the desire to gain market share, and often substantial resources.” The seriousness of entry depends on two main things: a) the barriers that exist against the new entrants in the business environment and b) the reaction of the existing competitors against the new entrants (Porter, 1998). The barriers in relation to the afghan marble cluster competitiveness are as follows:

1. Economies of scale: for a new entrant into the cluster, it is essential to reduce the unit cost of production in order to be able to compete with the existing companies; to do so the new company needs to establish with large scale. This requires huge capital cost. According to the OTF group estimations, “with a minimum project cost of $500,000 for a quarry and over $1 million for a plant it is difficult for SMEs to invest. Most of the businesses operating in the Afghan marble industry today are relatively small and even with loans; they cannot put up 30-40% equity stake” (the OTF group, 2006). There is potential for foreign investors to capture economies of scale in Afghanistan and compete very easily with the domestic producers.

2. Product differentiation: “brand identification creates a barrier by forcing entrants to spend heavily to overcome customer loyalty” (Porter, 1998). However, the marble

products in Afghanistan are not known under any specific brand; they are considered

as the afghan marble under several different names regardless of the names of the

companies who produce them. So, product differentiation does not remain a barrier to entry into the cluster.

3. Capital requirements: as mentioned above, the huge fixed cost plus some variable

costs to establish a quarry as well as a processing plant is a real barrier for the new entrants. “Few banks in Afghanistan are giving business loans to projects of this size. The cost of financing and inability to put together an adequate business plan are further impediments to accessing financing” (the OTF group, 2006).

4. Cost disadvantages: there are certain advantages that stem from past experience as companies keep practicing the same manufacturing process for years and years. This is referred to as the “experience curve,” which gets improving in terms of knowledge and skills of the workers in a company as time goes on. This could be considered a barrier for a new entrant in the afghan marble cluster; however, it is not so serious because the existing competitors practices in terms of the international standards are not so well and therefore, there is potential for a new entrant to establish putting up the standard practice, which has not been experienced by any of the existing practitioners in the cluster. This is true especially with the new technology and machineries innovated for the industry worldwide, but not yet practiced by the afghan processors.

5. Access to distribution channels: the level of production for the domestic marble in Afghanistan is not at a level to require very complicated distribution channel; it is taking place through a number of retail shops at several specified marketplaces for marble. The retail shops are supplied by the marble processing companies. In few cases the SMEs have established their own distribution points, but in general the same retail shops are supplied by the same or different marble processing companies. As a whole, access to “distribution channel” does not seem to be a serious barrier for the new entrants.

6. Government policy: government has influenced the industry greatly by setting policies that do not easily facilitate the development of the cluster. The pricing policy for quarrying of marble is not fair. Although it is claimed to be through a full and open competitive process, the minimum cost for royalty fee has not been set competitively in compare with the quarries in Pakistan, Iran, and India—the neighboring countries. The ministry’s not initiating policies, strategies and tactics to facilitate and enforce development of the cluster. As mentioned in previous sections, the expertise at the ministry is very focused around the geological aspect of the minerals rather than the business side of it, which causes the ministry personnel to rarely think about the economy and business part of the mineral industries. There are a lot of rooms for improvement in terms of effective policies and new strategies/tactics, which by itself is the biggest barrier against the development of the cluster at this time. Currently the Ministry’s pricing policy for quarrying contracts is in no way competitive; this is why 65% of companies that established did not produce a single tile since 2001 and 14% of companies that established could only continue until early 2008. Government policy is the biggest barrier against the development of the cluster at the moment.

In addition to the barriers discussed above “the potential rival’s expectations about the reaction of existing competitors” also influences their decision to enter into the marble cluster. However, this does not seem to be a big challenge; it is a matter of establishing good relationship with the existing competitors on the ground. The AMGPA, as the association to promote marble cluster, can always play a positive role in this regard. Bargaining power of suppliers: “Suppliers can exert bargaining power on participants in an industry by raising prices or reducing the quality of purchased goods and services” (Porter, 1998). From the author’s perspective, suppliers for marble production in Afghanistan are classified into two categories: a) primary suppliers consisting of companies that provide raw materials (blocks) to the processing plants and b) secondary suppliers that include companies that provide machineries, spare parts, and lubrications to both the quarry operations as well as the processing plants.

a) Primary suppliers are referred to the block producers that supply the processing plants with raw materials—the marble blocks. Level of power of the primary suppliers depends on the status of the following conditions influencing their power:

Dominance by few quarrying companies: In terms of block suppliers, there are five companies and/or individuals who hold contracts from the Ministry of Mines to do the quarrying operations and supply marble blocks to the processing plants. The limited number of block suppliers is not a good idea for the cluster. The few suppliers can hold the power to “squeeze profitability” out of the cluster and leaving the cluster unable to recover cost increases. The limited number of block suppliers is because of the unhealthy government policies.

Product differentiation: The blocks are mostly extracted by explosives, and therefore producing badly shaped blocks to the processing plants. Only few companies: Mir Limited and Madan Limited use wire saw in Hirat province to produce regular blocks; these are the only two companies producing standard marble blocks to the processing plants. Their products are differentiated; they come with regular shapes reducing the processing wastage to a large extent. Being few and the only producers of differentiated blocks, the two companies have the power of supplying raw materials to the processing plants

Integration of suppliers in the actual marble business: Some of the block suppliers are the ones who supply their own processing plants as well as others. This practice gives a weaker position for the rest of the processing plants to compete in terms of production.

Importance of marble industry to the block suppliers: Although some of the block suppliers supply their own processing plants they also end up with surplus amount of blocks that they need to sell. Therefore, the marble industry is very important for them to absorb their surpluses. For the rest of the block suppliers the industry is the only source of raw material, except for the ones exporting blocks to other countries. Having said this, the processing plants are not so much under pressure by the suppliers of blocks. But still it is a factor that might give power to suppliers of blocks as situation changes.

b) Secondary suppliers are referred to providers of machineries, spare parts, lubrications, fuel, etc. that move the whole process of production in the quarries as well as in the processing plants. The suppliers are usually international companies located outside the country mainly in Pakistan and China. Firstly Afghanistan and secondly marble cluster as a whole is only a minor segment amongst their target buyers. Therefore, they have un-influence-able power over the afghan buyers in the marble cluster. The Afghan members of marble cluster have to follow the overall trend of the market. Bargaining power of buyers: Customers also “can force down prices, demand higher quality or more service, and play competitors off against each other” (Porter, 1998). The power of buyers depends on the status of the following factors in the afghan marble market:

Large-volume purchases: Marble is used as “dimension stone” for construction purposes; most of the consumers are small private construction projects. Purchases are usually in small scale filling the demand of the domestic buyers; they take place in large-volumes occasionally and only when there are some large construction projects. For example, construction of the new terminal-building for Kabul Airport was one of the large projects, which was supplied with afghan marble dimension stone last year. In summary, purchases are not concentrated or in large volumes to give a powerful position to the buyers; therefore, buyers cannot act collectively and influence the cluster.

Differentiation versus standard products: A buyer can be powerful if “products it purchases from the industry are standard or undifferentiated” (Porter, 1998). As mentioned in previous sections, the nature of demand is very simple in the afghan marble market. Marble is consumed only in the form of tiles in several standard sizes for construction purposes. Buyers have stronger position because they can access the same marble sizes from different suppliers.

Marble being a component of a larger project: The marble buyers have powerful position in buying marble products because marble is usually used as a single component of a larger construction project. Therefore, “the buyers are likely to shop for a favorable price and purchase selectively” (Porter, 1998).

Threat of substitute products: “In Porter’s model, substitute products refer to products in other industries” (Quick MBA, 2007). For example, substitute products for marble tiles are products coming in the form of mosaic tiles, ceramic tiles, granite, and other dimension stones. “By placing a ceiling on prices it can charge, the substitute products or services limit the potential of an industry” (Porter, 1998). Substitute products for marble tiles in terms of price are much lower and accessible by the average consumers—the largest number of consumers in the segment. Consumers of marble tiles are mostly construction projects; most of the consumers are the average people—from the economic perspective—who do not prefer costly products. Substitute products are cheaper and available in different colors and designs. The government as well as the members of the marble cluster needs to follow such pricing strategies and tactics that could place the industry in a better position to compete with the substitutes.

Rivalry among existing competitors: According to Michael Porter, this rivalry “takes the familiar form of jockeying for position—using tactics like price competition, product introduction, and advertising slugfests” (Porter, 1998). This rivalry—in the context of the afghan marble market—can be influenced by different factors such as the following:

· Number of competitors in the cluster: competitors in the marble cluster are not so many and are limited to the domestic companies. Out of these companies, only 14% that established operations in 2001 have been able to continue operation; the rest gave up and went bankrupt. The competitors are roughly same in size and less different in terms of capacity from each other. Rivalry is not so complicated within the cluster at this time because as the number of companies increases; they have to be still competing for the same number of customers, which makes the nature of competition more complicated.

· Slow market growth for the cluster: Marble cluster growth is taking place very slowly. The companies need to fight for market share in order to improve revenues as a result of expanded market share.

· Fixed costs: Capital cost—the part that goes to fixed cost—for establishing of a marble processing plant is huge, which makes the companies to produce near capacity production to attain the lowest unit cost possible. This can result an increase in rivalry, but for the time being, most of the existing companies are same in size as well as in terms of type of technology. Therefore, the rivalry issue is not that hard.

· Low switching costs: there is no switching cost for marble buyers to change their suppliers. This can result increased rivalry amongst the marble producers.

· Product differentiation: marble products are limited to dimension stones—usually tiles in different sizes. There is very low level of differentiation; this can also result increased rivalry.

· Exit barriers: since the capital cost for setting up a marble processing plant is huge, it makes it difficult for a company to withdraw and exit from the business. The equipments and machineries are very specialized to the marble manufacturing; they cannot be sold so easily. To exit from the business is very difficult and almost impossible. Therefore, one needs to continue and compete.

· Diversity of rivals: Diversity of rivals in terms of culture, type of people, etc. can make an industry unstable (Quick MBA, 2007). Marble processors in Afghanistan are all domestic and coming from the same culture and history; this makes the rivalry understandable and intense.

Afghan Government and Private Sector Join Forces to Strengthen Marble Industry KABUL, AFGHANISTAN | MAY 11, 2013 –

Afghanistan is home to 60 known deposits of 35 varieties of marble. To promote the growth of this sector, the Export Promotion Agency of Afghanistan (EPAA), and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) organized a seminar on exports of the country’s high-quality marble products. The seminar presented an opportunity for the representatives of Afghan marble associations, marble traders, officials from the Afghan Marble Center of Excellence and other government officials to discuss challenges to trade and strategies to boost Afghanistan’s marble exports.

· Minister of Commerce and Industries Anwar-ul-Haq Ahadi opened the seminar by highlighting the vast potential of Afghanistan’s marble industry. “Afghanistan can export $700 million to $800 million of marble to other countries,” said Minister Ahadi.

· The marble deposits of Herat province in western Afghanistan, Nangarhar province in eastern Afghanistan, Wardak province in central Afghanistan, and Helmand province in southern Afghanistan are of similar, or better quality than the world’s biggest marble exporters, including countries such as Italy.

· “The current world market for marble imports is estimated at $3.5 billion,” said Deputy Mission Director Jerry Bisson, noting that the industry has the potential to be a driving force in Afghanistan’s economy.

· The seminar covered the issue of taxation on exports of Afghanistan’s processed marble; imports of low-quality marble from neighboring countries; tariffs imposed by other countries on marble coming from Afghanistan; and the best transport corridors for Afghanistan’s marble exports.

· The seminar is one of many USAID efforts to facilitate the Afghan Government and private sector partnership in resolving challenges to trade and exports. Afghanistan has vast reserves of marble, minerals, and precious stones that can strengthen the economy, create jobs, attract investment, and improve livelihoods.

(http://afghanistan.usaid.gov/en/USAID/Article/2976/Afghan_Government_and_Private_Sector_Join_Forces_to_Strengthen_Marble_Industry)

Date: 2015-01-29; view: 1066

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| The national demand for Afghanistan | | | Second Afghanistan International Marble Conference |