CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Changes in the phonetic system in Middle English. Vowels in the unstressed position. Vowels under stress. Quantitative changes.

All vowels in the unstressed position underwent a qualitative change and became the vowel of the type of [ý] or [e] unstressed. This phonetic change had a far-reaching effect upon the system of the grammatical endings of the English words which now due to the process of reduction became homonymous. For example:

—forms of strong verbs

Old English writan — wrat — writon — writen

with the suffixes -an, -on, -en different only in the vowel component became homonymous in Middle English:

writen — wrpt — writen — writen

—forms of nouns

Old English Nominative Plural a-stem fiscas

Genitive Singular fisces

Middle English for both the forms is fisces;

Or Old English Dative Singular fisce

Genitive Plural fisca

Middle English form in both cases is fisce.

Vowels under stress

Besides qualitative changes .mentioned above vowels under stress underwent certain changes in quantity.

— Lengthening of vowels

The first lengthening of vowels took place as early as late Old English (IX century). All vowels which occurred before the combinations of consonants such as mb, nd, Id became long. Old English Middle English (New English) [i] > [i:]

climban climben climb

findan finden find

cild cild child

[u] > [u:] hund hound hound

The second lengthening of vowels took place in Middle English (XII—XIII century). The vowels [a], [o] and [e] were affected by the process. This change can be observed when the

given vowels are found in an open syllable.

— Shortening of vowels

All long vowels were shortened in Middle English if they are found before two consonants (XI century).

Through phonetic processes the lengthening and the shortening of vowels mentioned above left traces in grammar and wordstock.

Due to it vowel interchange developed in many cases

between:

— different forms of the same word;

— different words formed from the same root.

For instance:

Middle English [i:] — [i] child children

[e:] — [e] kepen but kept

[i:] — [i] wis wisdom

23. Changes in the phonetic system in Middle English. Consonants.

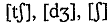

The most important change in the consonant system that can be observed if we compare the Old English and the Middle English consonant system will be the development of the fricative consonant [ʃ] and the affricates [tʃ] and [dƷ] from Old English palatal consonants or consonant combinations.

Thus we can notice that variants of some Old English consonant phonemes developed differenly. For example:

The phoneme denoted in Old English by the letter ñ had two variants: [k] — hard and [k’] — palatal, the former remaining unchanged, the latter giving us a new phoneme, the phoneme [tʃ] .

Special notice should be taken of the development of such consonant phonemes that had voiced and voiceless variants in Old English, such as:

[f] — [v] in spelling f

[s] — [z] in spelling s

24. Changes in the phonetic system in New English. Vowels in the unstressed position. Vowels under stress. Qualitative changes.

Vowels in the unstressed position already reduced in Middle English to the vowel of the [ə] type are dropped in New English if they are found in the endings of words, for example:

Old English Middle English New English

Nama name name [neim]

The vowel in the endings is sometimes preserved — mainly for phonetic reason: wanted, dresses

— without the intermediate vowel it would be very difficult to çronounce the endings of such words.

Vowels under stress

Qualitative changes

— Changes of monophthongs

All long monophtongs in New English underwent a change that is called The Great Vowel Shift. Due to this change the vowels became more narrow and more front.

Two long close vowels: [u] and [i] at first also became more narrow and gave diphthongs of the [uw] or [ij] type. But those diphthongs were unstable because of the similarity between the glide and the nucles.

Consequently the process of the dissimilation of the elements of the new diphthongs took place and eventually the vowels [i] and [u] gave us the diphthongs [ai] and [au], respectively.

Middle English New English

[u]>[au] hous house

[i]>[ai] time time

Influence of the consonant “r” upon the Great Vowel Shift.

When a long vowel was followed in a word by the consonant “r” the given consonant did not prevent the Great Vowel Shift, but the resulting vowel is more open, than the resulting vowel in such cases when the long vowel undergoing the Shift was followed by

a consonant other than "r".

As a result of the Great Vowel Shift new sounds did not appear, but the already existing sounds appeared under new conditions. For instance:

The sound existed

before the Shift

[ei] wey

[u:] hous

[i:] time

The sound appeared after the Shift

[ei] make

[u:] moon

[i:] see, etc.

Two short monophthongs changed their quality in new English (XVII century), the monophthong [a] becoming [ae] and the monophthong [u] becoming [ʌ]. For instance:

Middle English New English

That that

Cut cut

However, these processes depended to a certain extent upon the preceding sound. When the sound [a] was preceded by [w] it changed into [o].

Where the sound [u] was preceded by the consonants [p], [b], [f], the change of [u] into [ʌ] generally did not take place,(bull, butcher, pull, push, full, etc.)

But sometimes even the preceding consonant did not prevent the change, for instance:

Middle English New English

[u] > [ʌ] but [but] but [b ʌ t]

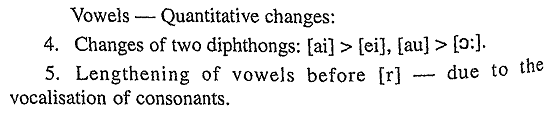

— Changes of diphthongs

Two out of the four Middle English diphthongs changed in New English, the diphthong [ai] becoming [ei] and the diphthong [au] contracted to [o:] For example:

Middle English New English

[ai] > [ei] dai day

[au]> [o:] lawe law

25. Changes in the phonetic system in New English. Vowels in the unstressed position. Vowels under stress. Quantitative changes.

Vowels in the unstressed position already reduced in Middle English to the vowel of the  type are dropped in New English if they are found in the endings of words, for example:

type are dropped in New English if they are found in the endings of words, for example:

Old English Middle English New English

Nama name name [neim]

writen write [rait]

writen write [rait]

sunu sone son [sAn]

The vowel in the endings is sometimes preserved — mainly for phonetic reason: wanted, dresses

- without the intermediate vowel it would be very difficult to pronounce the endings of such words.

Vowels in the unstressed position.

Quantitative changes

Among many cases of quantitative changes of vowels in New English one should pay particular attention to the lengthening of the vowel, when it was followed by the consonant [r]. Short vowels followed by the consonant [r] became long after the disappearance of the given consonant at the end of the word or before

another consonant:

Middle English New English

[a] > [a:] farm farm

[o] > hors horse

[o] > hors horse

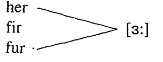

When the consonant [r] stood after the vowels [e], [i], [u], the resulting vowel was different from the initial vowel not only in quantity but also in quality. Compare:

or [h] before [t]: might, night, light.

Summary

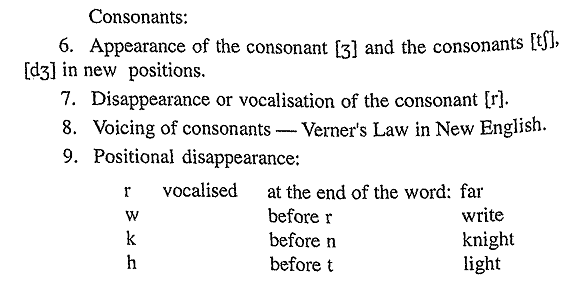

26. Changes in the phonetic system in New English. Consonants.

The changes that affected consonants in New English are not very numerous. They are as follows.

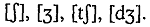

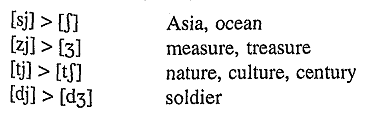

1) Appearance of a new consonant in the system of English phonemes —  and the development of the consonants [d3] and

and the development of the consonants [d3] and  from palatal consonants.

from palatal consonants.

Thus Middle English [sj], [zj], [tj], [dj] gave in New English the sounds

For example:

Note should be taken that the above-mentioned change took place in borrowed words, whereas the sounds  which appeared in Middle English developed in native words.

which appeared in Middle English developed in native words.

2. Certain consonants disappeared at the end of the word or before another consonant, the most important change of the kind affecting the consonant [r]:

farm, form, horse, etc.

3. The fricative consonants  were voiced after Unstressed vowels or in words having no sentence stress — the so-called "Verner's Law in New English":

were voiced after Unstressed vowels or in words having no sentence stress — the so-called "Verner's Law in New English":

possess, observe, exhibition; dogs, cats; the, this, that,

there, then, though, etc.

Summary

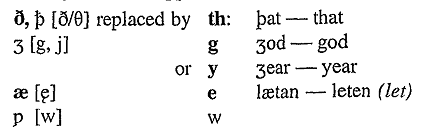

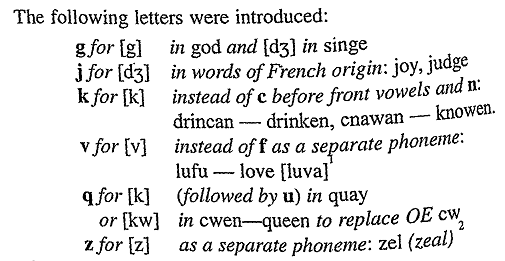

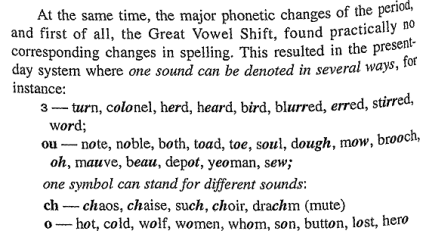

27. Changes in the phonetic system in New English. Changes in alphabet and spelling in Middle and New English.

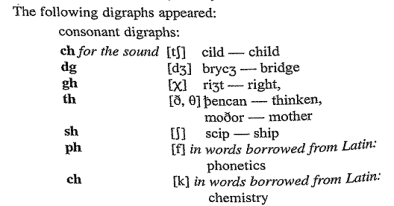

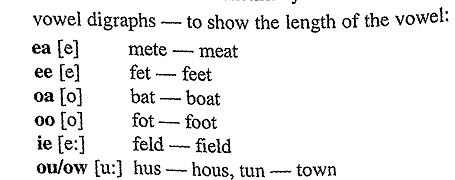

As we remember, the Old English spelling system was mainly phonetic. However, the 13th and 14th centuries witnessed many changes in the English language, including its alphabet and spelling. As a result of these modifications the written form of the word became much closer to what we have nowadays.

In Middle English the former Anglo-Saxon spelling tradition was replaced by that of the Norman scribes reflecting the influence of French and often mixing purely phonetic spelling with French spelling habits and traditions inherited from Old

English. The scribes substituted the so-called "continental variant" of the Latin alphabet for the old "insular writing". Some letters, already existing in Old English but being not very frequent there, expanded their sphere of use — like the letter k. New letters were added — among them j , w, v and z. Many digraphs — combinations of letters to denote one sound, both vowel and consonant —

appeared, mostly following the pattern of the French language.

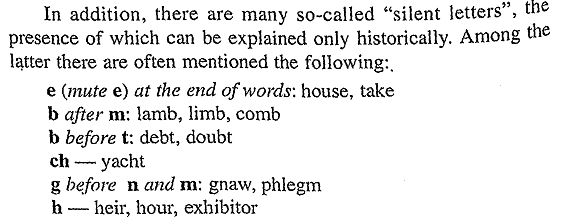

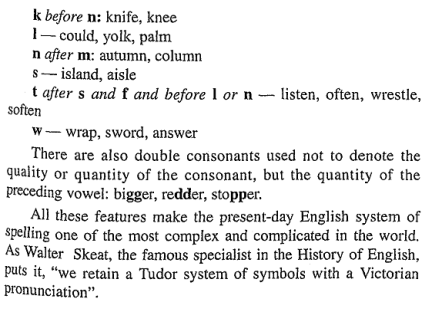

The following letters disappeared:

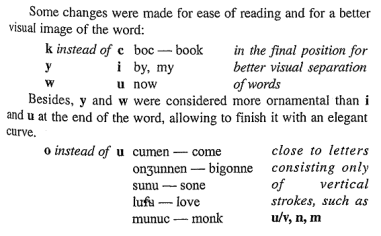

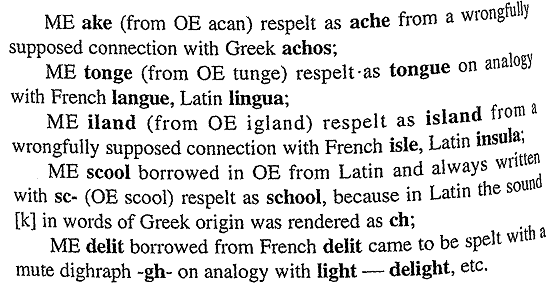

The New English period witnessed the establishment of the literary norm presupposing a stable system of spelling. However, the spelling finally fixed in the norm was influenced by many factors, objective and subjective in character, preserving separate elements of different epochs and showing traces of attempts to

improve or rationalise it.

In New English with the revival of learning in the 16th century a new principle of spelling was introduced, later to be called etymological. It was believed that, whatever the pronunciation, the spelling should represent to the eye the form

from which the word was derived, especially in words of Latin or Greek origin. Thus,.the word dett borrowed from French dette was respelled as debt, for it could be traced to Latin debitum, dout borrowed from French douter — as doubt from Latin dubitare.

However, the level of learning at that age was far from Perfect, and many of the so-called etymological spellings were Wrong. Here it is possible to mention such words as:

28. General survey of grammar changes in Middle and New English. The noun. Middle English. Morphological classification. Grammatical categories.

General survey of grammar changes

in Middle and New English

The grammar system of the language in the Middle and New English periods underwent radical changes. As we remember, principal means of expressing grammatical relations in Old English were the following:

—suffixation

— vowel interchange

— use of suppletive forms,

all these means being synthetic.

In Middle English and New English many grammatical notions formerly expressed synthetically either disappeared from the grammar system of the language or came to be expressed by analytical means. There developed the use of analytical form

consisting of a form word and a notional word, and also word order, special use of prepositions, etc. — analytical means.

In Middle English and New English we observe the process or the gradual loss of declension by many parts of speech, formerly declined. Thus in Middle English there remained only three declinable parts of speech: the noun, the pronoun and the adjective, against five existing in Old English (the above plus the infinitive and the participle)-In New English the noun and the pronoun (mainly personal) are the

only parts of speech that are declined.

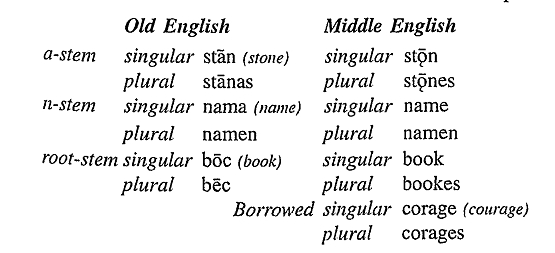

The noun Middle English Morphological classification

In Old English there were three principal types of declensions: a-stem, n-stem and root-stem declension, and also minor declensions — i-stem, u-stem and others. These types are preserved in Middle English, but the number of nouns belonging to the same declension in Old English and Middle English varies. The n-stem declension though preserved as a type has lost many of the nouns belonging to it while the original a-stem declension grows in volume, acquiring new words from the original n-stem, root-stem declensions, and also different groups of minor declensions and also borrowed words. For example:

Grammatical categories

There are only two grammatical categories in the declension of nouns against three in Old English: number and case, the category of gender having been lost at the beginning of the Middle English period.

Number

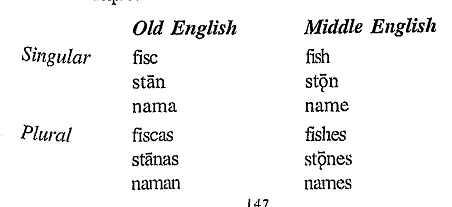

There are two number forms in Middle English: Singular and Plural. For example:

Case

The number of cases in Middle English is reduced ascompared to Old English. There are only two cases in Middle English: Common and Genetive, the Old English Nominative, Accusative and Dative case having fused into one case -

the Common case at the beginning of Middle English.

For example:

Thus we see that the complicated noun paradigm that existed in Old English was greatly simplified in Middle English, which is reflected in the following:

1) reduction of the number of declensions;

2) reduction of the number of grammatical categories;

3) reduction of the number of categorial forms within one of the two remaining grammatical categories — the category of case.

29. New English. Morphological classification. Origin of irregular noun forms. Grammatical categories.

New English The process of the simplification of the system of noun declension that was manifest in Middle English continued at the beginning of the New English period.

Morphological classification

In Old English we could speak of many types of consonant and vowel declensions, the a-, n- and root-stem being principal among them. In Middle English we observe only these three declensions: a-stem, n-stem, root-stem. In New English we do not find different declensions, as the overwhelming majority of nouns is declined in accordance with the original a-stem declension masculine, the endings of the plural form -es and the Possessive -s being traced to the endings of the original a-stem declension masculine.

Of the original n-stem and root-stem declensions we have in New English but isolated forms, generally referred to in modern grammar books as exceptions, or irregular noun forms.

Origin of modern irregular noun forms

All modern irregular noun forms can be subdivided into several groups according to their origin:

a) nouns going back to the original a-stem declension, neuter gender, which had no ending in the nominative and accusative plural even in Old English, such as: sheep — sheep (OE sceap — sceap)

deer — deer (OE deor — deor)

b) some nouns of the n-stem declension preserving their plural form, such as: ox — oxen (OE oxa — oxan)

c) the original s-stem declension word : child — children (Old English cild — cildra)

d) remnants of the original root-stem declension, such as: foot — feet (OE fot — fet) tooth — teeth (OE to6 — ted)

e) "foreign plurals" — words borrowed in Early New English from Latin. These words were borrowed by learned people from scientific books who alone used them, trying to preserve their origin form and not attempting to adapt them to their native language. Among such words are:

datum — data, automaton — automata, axis — axes, etc.

It should be noted that when in the course of further history these words entered the language of the whole people, they tended to a regular plural endings, which gave rise to such doublets as:

molecula—moleculae and moleculas,

formula —formulae and formulas,

antenna—antennae and antennas, the irregular form being reserved for the scientific style.

Grammatical categories

The category of gender is formal, traditional already in Old English; in Middle English and New English nouns have no category îò gender.

The category of number is preserved, manifesting the difference between singular and plural forms.

The category of case, which underwent reduction first to three and then to two forms, in New English contains the same number of case-forms as in Middle English, but the difference is the number of the nouns used in the Genitive (or Possessive) case — mainly living beings, and the meaning — mainly the quality or the person who possesses something.

the boy's book, a women's magazine, a two miles' walk

Inanimate nouns are not so common: the river's bank, the razor's edge

In Modern English, however, we observe a gradual spreading of the ending -s of the Possessive case to nouns denoting inanimate things, especially certain geographical notions, such cases as England's prime minister" being the norm, especially in political style.

30. New English. The adjective. The pronoun. The article.

Only two grammatical phenomena that were reflected in the adjectival paradigm in Old English are preserved in Middle English: declension and the category of number.

The difference between the Indefinite (strong) and the Definite (weak) declension is shown by the zero ending for the former and the ending -e for the latter, but only in the Singular. The forms of the Definite and the Indefinite declension in the Plural have similar endings.

For instance:

Indefinite a yong squier

yonge

Definite the yonge sonne

In New English what remained of the declension in Middle English disappeared completely and now we have the uninflected form for the adjective used for all purposes for which in Old English there existed a complicated adjectival paradigm with two number-forms, five case-forms, three gender-forms and two declensions.

All grammatical categories and declensions in Middle and New English disappeared.

It should be noted, however, that out of the three principal means of forming degrees of comparison that existed in Old English suffixation, vowel interchange and suppletive forms, there remained a productive means only one: suffixation, the rest of the means see only in isolated forms.

The pronoun Nowadays what remained of the pronominal declension is mainly represented by the declension of the personal pronoun and on a small scale — demonstrative and interrogative (relative).

Case The four-case system that existed in Old English gave way to a two-case system in late Middle English and in New English.

Gender As a grammatical phenomenon gender disappeared already in Middle English, the pronouns he and she referring only to animate notions and it — to inanimate.

Number The three number system that existed in Early Old English Singular, Dual, Plural) was substituted by a two number system already in Late Old English.

The article The first elements of the category of the article appeared already in Old English, when the meaning of the demonstrative pronoun was weakened, and it approached the status of an article in such phrases as: Se mann (the man). 153 page

The form of the definite article the can be traced back to the Old English demonstrative pronoun se (that, masculine, singular), which in the course of history came to be used on analogy with the forms of the same pronoun having the initial consonant and began to be use with all nouns, irrespective of their gender or number.

The indefinite article developed from the Old English numeral an. In Middle English an split into two words: the indefinite pronoun an, losing a separate stress and undergoing reduction of its vowel, and tne numeral one, remaining stressed as any other notional word. Later the indefinite pronoun an grew into the indefinite article a/an, and together with the definite article the formed a new grammatical category — the category of determination, or the category of article.

31. Old English. General characteristics. Means of enreaching vocabulary. Internal means. External means.

General characteristics

The vocabulary of Old English was rather extensive. It is said to have contained about 50 000 words. These words were mainly native words. They could be divided into a number or strata. The oldest stratum was composed of words coming from the Common Indo-European parent tongue.

Compare:

Old English New English Latin Russian

modor mother mater ìàòü

neowe new novus íîâûé

Another layer, relatively more recent, was words inherited by English and other Germanic languages from the same common Germanic source.

Old English New English German

land land Land

grene green grim

The third stratum, and that not very extensive, was made up of words that existed only in English, for instance, the word clypian (to call), the root preserved in the now somewhat obsolete word yclept (named).

There are two principal ways of enriching the vocabulary of a language: internal means — those that are inherent in the language itself, and external means, which result from contacts between peoples.

Means of enriching vocabulary

Internal means: word derivation, primarily affixation and vowel interchange, and word composition.

— Word derivation

In Old English affixation was widely used as a wordbuilding means.

There were very many suffixes, with the help of which new nouns, adjectives, adverbs and sometimes verbs were formed, for instance:.

noun suffixes of concrete nouns: -ere fisc+ere (fisher) , denoting the doer of the action

noun suffixes of abstract nouns: -dom freo+dom. (freedom) , -had cild+had (childhood)

adjective suffixes: -isc Engl+isc (English), Frens+lSC (French), -ful car+ful (careful)

Prefixes were used on a limited scale and they generally had a negative meaning: mis- mis+ded (misdeed)

Vowel interchange:

Noun verb

dom (doom) deman (to deem)

Word composition

Nouns: Engla+land (land of the Angles, England)

Adjectives: Ic+ceald (ice-cold)

External means of enriching vocabulary

(Old English borrowings)

The main borrowings that we can single out in Old English were Latin and Celtic borrowings.

— Latin borrowings

The first Latin borrowings entered the language before the Germanic tribes of Angles, Saxons, Jutes and Frisians invaded the British Isles. The first stratum of borrowings are mainly words connected with trade. Many of them are preserved in Modern English, such as: pound, inch, pepper, cheese, wine, apple, pear, plum, etc.

The second stratum of words was composed of loan Latin words that the Germanic tribes borrowed already on British soil from the romanized Celts, whom they had conquered in the 5 century. Those were words connected with building and architecture, as the preserved nowadays: tile, street, wall, mill, etc.

The third stratum of Latin loan words was composed of words borrowed after the introduction of the Christian religion. They are generally of a religious nature, such as the present-day words: bishop, devil, apostle, monk.

As Latin was the language of learning at the time, there also entered the language some words that were not directly connected with religion, such as: master, school, palm, lion, tiger, plant, astronomy, etc.

— Celtic borrowings

The Celtic language left very few traces in the English language, because the Germanic conquerors partly exterminate the local population. The Celtic-speaking people who remained on the territory occupied by the Germanic tribes were slaves, and even those were not very numerous. Among the few borrowed words we can mention: down (the downs of Dover), binn (bin - basket, crib, manger).

Some Celtic roots are preserved in geographical names, such

as: kil (church — Kilbrook), ball (house — Ballantrae), esk (water —river Esk) and some others.

32. Middle English. General characteristics. Means of enreaching vocabulary. Internal means. External means.

General characteristics

Many words became obsolete, many more appeared in the rapidly developing language under the influence of contacts with other nations.

Internal means of enriching vocabulary

Though the majority of Old English suffixes are still preserved in Middle English, they are becoming less productive, and words formed by means of word-derivation in Old English can be treated as such only etymologically. Words formed by means of word-composition in Old English, in Middle English are often understood as derived words.

External means of enriching vocabulary

The principal means of enriching vocabulary in Middle English are not internal, but external borrowings. Two languages in succession enriched the vocabulary of the English language of the time — the Scandinavian language and the French language.

— Scandinavian borrowings

The Scandinavian invasion and the subsequent settlement of the Scandinavians on the territory of England brought about many changes in different spheres of the English language: wordstock, grammar and phonetics.

Many words were borrowed from the Scandinavian language, for example:

Nouns: law, fellow, sky, skirt, skill, skin, egg, anger,cake, husband, leg, wing, guest, loan, race

Adjectives: big, week, wrong, ugly, twin

Verbs: call, cast, take, happen, scare, hail, want, bask,gape, kindle

Pronouns: they, them, their; and many others.

The conditions and the consequences of various borrowings were different.

1. Sometimes the English language borrowed a word for which it had no synonym: law, fellow

2. The English synonym was ousted by the borrowing. Scandinavian taken (to take) and callen (to call) ousted the English synonyms niman and clypian, respectively.

3. Both the words, the English and the corresponding Scandinavian, are preserved, but they became different in meaning: Native heaven, starve Scandinavian sky, die

4. Sometimes a borrowed word and an English word are etymological doublets, as words originating from the same source in Common Germanic: shirt skirt

5. Sometimes an English word and its Scandinavian doublet were the same in meaning but slightly different phonetically. For example, Modern English to give, to get come from the Scandinavian gefa, geta.

6. There may be a shift of meaning. Thus, the word dream originally meant "joy, pleasure"; under the influence of the related Scandinavian word it developed its modern meaning.

French borrowings

stands to reason that the Norman conquest and the subsequent history of the country left deep traces in the English language, mainly in the form of borrowings in words connected such spheres of social and political activity where French speaking Normans had occupied for a long time all places of importance. For example:

government and legislature: government, noble, baron, prince, duke, court, justice, judge, crime, prison, condemn, sentence, parliament, etc.

military life: army, battle, peace, banner, victory, general, colonel, lieutenant, major, etc.

religion: religion, sermon, prey, saint, charity

city crafts: painter, tailor, carpenter

pleasure and entertainment: music, art, feast, pleasure, leisure, supper, dinner,pork, beef, mutton

words of everyday life: air, place, river, large, age, boil, branch, brush, catch, chain, chair, table,

relationship: aunt, uncle, nephew, cousin.

The place of the French borrowings within the English language was different:

1. to denote notions unknown to the English up to the time: government, parliament, general, colonel, etc.

2. The English synonym is ousted by the French borrowing: English French here army

3. Both the words are preserved, but they are stylistically different: English French to work to labour, to leave to abandon, life existence

4. Sometimes the English language borrowed many words with the same word-building affix. "government", "parliament", "agreement", but later there appeared such English-French hybrids as:

fulfilment, amazement.

The suffix -ance/-ence, which was an element of such borrowed words as "innocence", "ignorance".

A similar thing: French borrowings "admirable", "tolerable", reasonable.

5. One of the consequences of the borrowings from French was the appearance of ethymological doublets: from the Common Indoeuropean: native borrowed fatherly paternal

6. Due to the great number of French borrowings there appeared in the English language such families of words, which though similar in their root meaning, are different in origin:

native borrowed

sun solar

see vision

7. There are caiques on the French phrase:

It's no doubt - Se n'est pas doute

Without doubt- Sans doute

Out of doubt - Hors de doute.

33. New English. General characteristic. Means of enriching vocabulary. Internal means.

The language in New English is growing very rapidly, the amount of actually existing words being impossible to estimate. Though some of the words existing in Old English and Middle English are no longer used in New English, the amount of new words exceeds the number of obsolete ones manifold.

In 1485 there ended the War between the Roses. The end of the war meant the end of feudalism and the beginning of capitalism, a new, more peaceful era and the transition between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. An absolute monarchy was established. It meant a real unification of the country, political and economic, resulted in the development of capitalism and made it inevitable that one nation and one national language be established. The long reign of Elizabeth I (1558—1603) was one of the most remarkable for the country, its progress in the discovery and colonizing field tremendous. Queen Elizabeth's reign was also particularly rich in learning — it was the age of Shakespeare, Sidney, Spencer, Bacon, Marlowe and many other famous names. Charles II, who during the time of Cromwell lived in exile in France, brought with him from the Continent a keen interest in scientific development, culture and arts, together with a considerable influence of the French language spoken by his supporters. As we have said, in New English there emerged one nationand one national language. But the English literary norm was formed only at the end of the 17* century, when there appeared the first scientific English dictionaries and the first scientific English grammar. In the 17* and 18* centuries there appeared a great number of grammar books whose authors tried to stabilize the use of the language. If the gradual acceptance of a virtually uniform dialect by all writers is the most important event in the emergence of Modern English, it must be recognised that this had already gone a considerable way before 1500, and it was undoubtedly helped by Caxton's introduction of printing in 1477. The fact that the London dialect was used by him in his translations and prefaces, and that Chaucer's works were among the books he published, led to its rapid diffusion throughout the country. But the adoption of a standard of spoken English was a slower process. Nevertheless, despite the persistence of wide varieties in pronunciation, the basic phonetic changes that distinguish Modern English from Middle English are profound, though they are not reflected in a similar modification of spelling. The most important of these changes was that affecting the sound of vowels and diphthongs, with the result that the "continental values" of Middle English were finally replaced by an approximation to modern pronunciation. Lesser changes also occurred in the pronunciation of consonants, though some ot these have since been restored by conscious, and often mistaken, attempts to adapt pronunciation more closely to the received spelling.

The language developed quickly at the beginning of the period and slowly — at the end (with the exception of the word-stock which develops equally quickly during the whole period). When the literary norm was formed, it, being always very conservative, prevented the change of the language, that is why the speed of the development slowed down

Word-stock. The vocabulary is changing quickly. Many new words are formed to express new notions, which are numerous. Ways of enriching the vocabulary: 1. inner means (conversion: hand => to hand); 2, outer means.

The principal inner means in New English is the appearance of new words formed by means of conversion. Usually new words are formed by acquiring a new paradigm and function within a sentence. Thus, book (a noun) has the paradigm book — books. Book (a verb) has the paradigm book — books — booked — booking, etc. (The book is on the table - He booked a room.) Similarly:

man (n) — man (v)

stone (n) — stone (v) — stone (adj)

(as in "a stone bench"), etc.

34. New English. General characteristic. Means of enriching vocabulary. External means.

The language in New English is growing very rapidly, the amount of actually existing words being impossible to estimate. Though some of the words existing in Old English and Middle English are no longer used in New English, the amount of new words exceeds the number of obsolete ones manifold.

In 1485 there ended the War between the Roses. The end of the war meant the end of feudalism and the beginning of capitalism, a new, more peaceful era and the transition between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. An absolute monarchy was established. It meant a real unification of the country, political and economic, resulted in the development of capitalism and made it inevitable that one nation and one national language be established. The long reign of Elizabeth I (1558—1603) was one of the most remarkable for the country, its progress in the discovery and colonizing field tremendous. Queen Elizabeth's reign was also particularly rich in learning — it was the age of Shakespeare, Sidney, Spencer, Bacon, Marlowe and many other famous names. Charles II, who during the time of Cromwell lived in exile in France, brought with him from the Continent a keen interest in scientific development, culture and arts, together with a considerable influence of the French language spoken by his supporters. As we have said, in New English there emerged one nationand one national language. But the English literary norm was formed only at the end of the 17* century, when there appeared the first scientific English dictionaries and the first scientific English grammar. In the 17* and 18* centuries there appeared a great number of grammar books whose authors tried to stabilize the use of the language. If the gradual acceptance of a virtually uniform dialect by all writers is the most important event in the emergence of Modern English, it must be recognised that this had already gone a considerable way before 1500, and it was undoubtedly helped by Caxton's introduction of printing in 1477. The fact that the London dialect was used by him in his translations and prefaces, and that Chaucer's works were among the books he published, led to its rapid diffusion throughout the country. But the adoption of a standard of spoken English was a slower process. Nevertheless, despite the persistence of wide varieties in pronunciation, the basic phonetic changes that distinguish Modern English from Middle English are profound, though they are not reflected in a similar modification of spelling. The most important of these changes was that affecting the sound of vowels and diphthongs, with the result that the "continental values" of Middle English were finally replaced by an approximation to modern pronunciation. Lesser changes also occurred in the pronunciation of consonants, though some ot these have since been restored by conscious, and often mistaken, attempts to adapt pronunciation more closely to the received spelling.

The language developed quickly at the beginning of the period and slowly — at the end (with the exception of the word-stock which develops equally quickly during the whole period). When the literary norm was formed, it, being always very conservative, prevented the change of the language, that is why the speed of the development slowed down

Word-stock. The vocabulary is changing quickly. Many new words are formed to express new notions, which are numerous. Ways of enriching the vocabulary:

1. inner means (conversion: hand => to hand);

2, outer means. The sources here are numberless, as the English have not only direct, but also indirect (through books, later — TV, radio, films) contacts with all the world. In the beginning of the Early New English (15th—16th century) — the epoch of the Renaissance — there are many borrowings from Greek, Italian, Latin. The ,17th century is the period of Restoration =>.borrowings come to the English language from French (a considerable number of these words being brought by Charles II and his court). In the 17th century the English appear in America => borrowings from the Indians' languages are registered. In the 18"1 century the English appear in India => borrowings from this source come to the English language (but these words are not very frequent, for they denote some particular reality of India, ex.: curry). In the 19* century the English colonisers appear in Australia and New Zealand => new borrowings follow (kangaroo). At the end of the 19th—beginning of the 20th century the English appear in Africa, coming to the regions formerly colonised by the Dutch => borrowings from Afrikaans and Dutch appear. Old English and Middle English Russian borrowings are scarce — the contacts between the countries and their peoples were difficult. In New English there are more borrowings: sable (very dark), astrakhan, mammoth; in the 20lh century — soviet, kolkhoz, perestroika, etc.

Very many new words appear in New English due to borrowing. It is necessary to say here that the process of borrowing, the sources of loan words, the nature of the new words is different from Middle English and their appearance in the language cannot be understood unless sociolinguistic factors are taken into consideration.

Chronologically speaking, New English borrowings may be subdivided into borrowings of the Early New English period XV—XVII centuries, the period preceeding the establishment of the literary norm, and loan words which entered the language after the establishment of the literary norm — in the XVIII—XX centuries, the period which is generally alluded to as late New English.

— Early New English borrowings (XV—XVII centuries)

Borrowings into the English language in the XV—XVII centuries are primarily due to political events and also to the cultural and. trade relations between the English people and peoples in other countries. Thus, in the XV century — the epoch of Renaissance, there appeared in the English language many words borrowed from the Italian tongue: cameo, archipelago, dilettante, fresco, violin, balcony, gondola, grotto, volcano; in the XVI century — Spanish and Portuguese words, such as: armada, negro, tornado, mosquito, renegade, matador. As a result of numerous Latin borrowings at the time there appeared many ethymological doublets:

Latin: strictum - (direct) strict; strait (through French)

Seniorem - senior ; sir

Faclum - fact; feat

In the XVII century due to relations with the peoples of America such words were borrowed as: canoe, maize, potato, tomato, tobacco, mahogany, cannibal, hammock, squaw, moccasin, wigwam, etc.

French borrowings — after the Restoration: ball, ballet, billet, caprice, coquette, intrigue, fatigue, naive.

—Late New English borrowings (XYIII—XX centuries)

— German:kindergarten, waltz, wagon, boy, girl

— French:magazine, machine, garage, police, engine, nacelle, aileron

— Indian:bungalow, jungle, indigo

— Chinese:coolie, tea

— Arabic:caravan, divan, alcohol, algebra, coffee, bazaar, orange, cotton, candy, chess

—Australian:kangaroo, boomerang, lubra — Russian:

Before the October Revolution the borrowings from the Russian language were mainly words reflecting Russian realia of the time: borzoi, samovar, tsar, verst, taiga, etc. After the Revolution there entered the English language such words that testified to the political role of this country in the world, as: Soviet, bolshevik, kolkhoz. Cultural and technical achievements are reflected in such borrowings as: sputnik, lunnik, lunokhod, synchrophasotron and recently such political terms as: glasnost, perestroika. In New English there also appeared words formed on the basis of Greek and Latin vocabulary. They are mainly scientific or technical terms, such as: telephone, telegraph, teletype, telefax, microphone, sociology, politology, electricity, etc.

35. Ethymological strata in Modern English. General characteristic. Native elements in Modern English. Common Indo-European stratum. Common Germanic stratum.

The English vocabulary of today reflects as no other aspect of the language the many changes in the history of the people andvarious contacts which the English speakers had with many nations and countries. The long and controversial history of the people is reflected in its vocabulary and especially in the number of loan words in it, different in origin and time of their entering the language and the circumstances under which the acquisition of the foreign element took place. So large is the number of foreign words in English that it might at first be supposed that the vocabulary has lost its Germanic nature. However, the functional role of the native element: the lotions expressed by native words, their regularity and frequency of occurrence, lack of restrictions to their use in written and oral speech of different functional styles, proves that the Germanic dement still holds a fundamental place, and the English vocabulary should be called Germanic.

Native element in Modern English

English native words form" two ethymological strata: the Common Indo-European stratum and the Common Germanic stratum.

Common Indo-European stratum

The words forming this stratum are the oldest in the vocabulary. They existed thousands of years B.C., at the time when it was yet impossible to speak about separate Indo- European languages, as well as about various nations in Europe. Words of the Common Indo-European vocabulary have been 'nherited by many modem Indo-European languages, not only Germanic, which is often a possible proof of these words belonging to the Common Indo-European stratum. Compare:

English Latin Russian

mother mater ìàòü

brother frater áðàò

two duo äâà

three tres òðè

Common Germanic stratum

There are also words inherited from Common Germanic Common Germanic is supposed to exist before it began splitting into various subgroups around the 1st century B.C.—Ã1 century A.D. These words can be found in various Germanic languages, but not in Indo-European languages other than Germanic.

English German Swedish

man mann man

green gran gron

The occurrence or non-occurrence of corresponding words in related languages is often a proof of their common origin. But, of course, the word could be borrowed from the same source into different languages, especially if we speak about languages in modern times.

36. Ethymological strata in Modern English. Foreign element in Modern English (borrowings). Latin element.

As we know, borrowed words comprise more than half the vocabulary of the language. These borrowings entered the language from many sources, forming consequently various ethymological strata. The principal ones here are as follows: — the Latin element — the Scandinavian element — the French element.

Latin element

The first Latin words entered the language of the forefathers of the English nation before they came to Britain. It happened during a direct intercourse and trade relations with the peoples of

The Roman empire. They mainly denote names of household •terns and products: apple, pear, plum, cheese, pepper, dish, kettle, etc. Already on the Isles from the Romanized Celts they borrowed such words as: street, wall, mill, tile, port, caster (camp — in such words as Lancaster, Winchester). Words of this kind denoted objects of Latin material culture. Latin words such as: altar, bishop, candle, church, devil, martyr, monk, nun, pope, psalm, etc. Were borrowed after the introduction of the Christian religion (7!h century), which is reflected in their meaning. The number of these words inherited from Old English is almost two hundred. We mentioned these words as Latin borrowings in the sense that they entered English from Latin, but many of them were Greek borrowings into Latin, such as bishop, church, devil and many others. Another major group of Latin borrowings entered English with the revival of learning (15th—I6ll! centuries). Latin was drawn upon for scientific nomenclature, as at the time the language was understood by scientists all over the world, it was considered the common name-language for science. These words were mainly borrowed through books, by people who knew Latin well and tried to preserve the Latin form of the word as much as possible. Hence such words as: antenna — antennae, index — indices, datum data, stratum — strata, phenomenon — phenomena, axi s— axes, formula — formulae, etc. Very many of them have suffixes which clearly mark them as

Latin borrowings of the time: — verbs ending in -ate, -ute: aggravate, prosecute — adjectives ending in -ant, -ent, -ior, -al: reluctant, evident, superior, cordial. These word-building elements together with the stylistic sphere of the language where such words are used are generally sufficient for the word attribution.

37. Ethymological strata in Modern English. Foreign element in Modern English (borrowings). Scandinavian element.

As we know, borrowed words comprise more than half the vocabulary of the language. These borrowings entered the language from many sources, forming consequently various ethymological strata. The principal ones here are as follows:

— the Latin element

— the Scandinavian element

— the French element.

Scandinavian element

Chronologically words of Scandinavian origin entered the language in the period between the 8th and the 10th centuries due to the Scandinavian invasions and settlement of Scandinavians on the British Isles, with subsequent though temporary union of two important divisions of the Germanic race. It is generally thought that the amount of words borrowed from this source was about 500, though some linguists surmise that the number could have been even greater, but due to the similarity of the languages and scarcity of written records of the time it is not always possible to say whether the word is a borrowed one or native, inherited from the same Common Germanic source.

Such words may be mentioned here, as:

they, then, their, husband, fellow, knife, law, leg,

wing, give, get, forgive, forget, take, call, ugly,

wrong.

As we said, words of Scandinavian origin penetrated into the English language so deeply that their determination is by no means easy. However, there are some phonetic/spelling features

of the words which in many cases make this attribution authentic enough. These are as follows:

— words with the sk/sc combination in the spelling, as:

sky, skin, skill, scare, score, scald, busk, bask

(but not some Old French borrowings as task, scare, scan, scape)

— words with the sound [g] or [k] before front vowels [i], [e]

fei], in the spelling i, e, ue, ai, a (open syllable) or at the end of

the word:

give, get, forgive, forget, again, gate, game, keg,

kid, kilt, egg, drag, dregs, flag, hug, leg, log, rig.

There are also personal names of the same origin, ending in •son:

Jefferson, Johnson

or place names ending in -ly, -thorp, -toft (originally meaning "village", "hamlet"):

Whitly, Althorp, Lowestoft.

These places are mainly found in the north-east of England, where the Scandinavian influence was stronger than in other parts of England.

38. Ethymological strata in Modern English. Foreign element in Modern English (borrowings). French element.

As we know, borrowed words comprise more than half the vocabulary of the language. These borrowings entered the language from many sources, forming consequently various ethymological strata. The principal ones here are as follows:

— the Latin element

— the Scandinavian element

— the French element.

French element

The French element in the English vocabulary is a large and important one. Words of this origin entered the language in the Middle and New English periods.

Among Middle English borrowings we generally mention earlier borrowings, their source being Norman French — the dialect of William the Conqueror and his followers. They entered

the language in the period beginning with the time of Edward the Confessor and continued up to the loss of Normandy in 1204.

Later Middle English borrowings have as their source Parisian French. The time of these borrowings may be estimated as end of the 13th century and up to 1500.

These words are generally fully assimilated in English and felt as its integral part:

government, parliament, justice, peace, prison, court, crime, etc.

Many of these words (though by no means all of them) are terms used in reference to government and courts of law.

Later Middle English borrowings are more colloquial words: air, river, mountain, branch, cage, calm, cost, table, chair.

The amount of these Middle English borrowings is as estimated as much as 3,500.

French borrowings of the New English period entered the language beginning with the 17th century — the time of the Restoration of monarchy in Britain, which began with the accession to the throne of Charles II, who had long lived in exile at the French court: aggressor, apartment, brunette, campaign, caprice, caress, console, coquette, cravat, billet-doux, carte blanche, etc.

Later also such words appeared in the language as: garage, magazine, policy, machine.

It is interesting to note that the phonetics of French borrowings always helps us to prove their origin.

These phonetic features are at least two: stress and special sound/letter features. Concerning the first (stress), words which do not have stress on the first syllable unless the first syllable is a

Prefix are almost always French borrowings of the New English period. Words containing the sounds [ ʃ ] spelled not sh, [ʤ] — not dg, [tʃ] — not ch and practically all words with the sound [ʒ] are sure to be of French origin: aviation, social, Asia, soldier, jury, literature, pleasure, treasure.

39. Ethymological strata in Modern English. Word-hybrids.

The extensive borrowing from various languages and assimilation of loan words gave rise to the formation in English of a large number of words the elements of which are of different origin — they are generally termed word-hybrids.

English French

be- -cause because

a- -round around

out cry outcry

over power overpower

fore front forefront

plenty ful plentiful

aim- -less aimless

re- take retake

English Scandinavian

par- take partake

bandy- leg bandy-legged

French Scandinavian

re- call recall

Latin French

juxta- position juxtaposition

40. Ethymological strata in Modern English. Ethymological doublets.

Ethymological doublets are words developing from the same word or root, but which entered the given language, in our case English, at different times of through different channels. Classifying them according to the ultimate source of the doublets we shall receive the following:

Ultimate Modern source doublets Period and channel

Common Indo-European

*pater fatherly native

paternal M.E. French borrowing

Common Germanic

*gher- yard native

garden M.E. French borrowing

*gens- choose native

choice M.E. French borrowing

*wer ward native

guard M.E. French borrowing

*sker shirt native

skirt M.E. Scandinavian borrowing

*skhed shatter native

scatter M.E. Scandinavian borrowing

Latin

discus disk O.E. Latin borrowing

disc N.E. Latin borrowing

moneta mint O.E. Latin borrowing

money M.E. Latin borrowing

Greek

adamas diamond Early M.E. French borrowing

adamant Later M.E. French borrowing

Hebrew

basam balm M.E. French borrowing

balsam N.E. Latin borrowing

The examples of various ethymological strata in the Modern English vocabulary mentioned above may serve as a sufficient testimony of a long and complicated .history of the English nation and the English language. They prove that language changes can be understood only in relation to the life of the people speaking the language.

Date: 2015-01-29; view: 15486

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Old English grammar. Morphological classification of verbs. Strong verbs. Weak verbs. | | | History of the Latin Writing System. |