CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

The Determination of Equilibrium Output

Output is determined by equilibrium in the goods market. The equilibrium condition is that production equals demand. Assume for now that production simply increases or decreases with demand without any change in price. Thus, in the short run, output is fully determined by demand. Then, we can write the equilibrium condition, Y=Z, as

Y= c0+c1(Y-T)+  +G. (3.4)

+G. (3.4)

The variable Y appears on both sides of this equation. On the LHS, Y represents production. On the RHS, Y represents national income. Chapter 2 explained why these two quantities are equal. The aim of this model is to determine Y, an endogenous variable. To solve the model, it is necessary to write Y as a function of the exogenous variables, i.e., those determined outside the model. In other words,

Y= [1/(1- c1 )][c0-c1T+  +G]. (3.5)

+G]. (3.5)

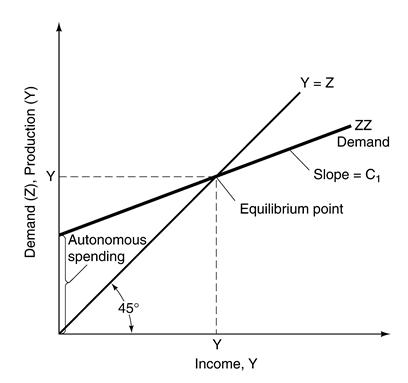

Equation (3.5) shows the algebraic solution and Figure 3.1 the graphical solution. In the graph, equilibrium occurs where demand (the ZZ curve) crosses the 45° line (i.e., the line along which Y=Z).

Figure 3.1: Equilibrium in the Goods Market

Equilibrium income is the product of two factors—autonomous spending (the second term in brackets in equation (3.5)) and a “multiplier” (the first term in brackets). Assume that autonomous spending is positive,[1] which (given that c1<1) will be true unless the budget surplus, T-G, is very large. The multiplier, which depends on the value of the propensity to consume, arises because consumption is affected by income. Suppose there is an increase in autonomous consumption—say, because of an increase in consumer confidence. The initial increase in consumption because of the rise in c0 leads to an increase in income. The increase in income leads to a further increase in consumption, which leads to a further increase in income, and so on. Thus, the effect of the initial increase in consumer confidence is “multiplied.” The multiplier captures this effect. The text describes a more formal way to think of the multiplier as the limit of a geometric series of fractional increases in consumption. A box also argues that a fall in consumer confidence was responsible for the 1991 recession.

4. Investment Equals Saving: An Alternative Way of Thinking about Goods Market Equilibrium

Private saving is defined as disposable income minus consumption, or

S=Y-T-C. (3.6)

Using this definition, the equilibrium output condition (Y=C+I+G) can be expressed as

I=S+(T-G). (3.7)

In a closed economy, investment equals private (consumer) saving (S) plus government saving (T-G). The quantity T-G is called the budget surplus. The quantity G-T is called the budget deficit.

5. Is the Government Really Omnipotent? A Warning

The equilibrium output condition (3.5) seems to imply that the government, by choosing G and T, has absolute control over the level of output. The text stresses that this chapter provides only a first pass at the analysis of fiscal policy. Later chapters will make clear the many limitations on the ability of the government to control output through spending and taxation.

Date: 2015-01-12; view: 2168

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| The Demand for Goods | | | The Constitution |