CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

A Primitive Theory of Exchange Value

I propose no definitive solution to the mystery. Once the inadequacy of formal economic theory is realized, and the complete unsophis-tication of anthropological economics thereby discovered, it is absurd to hope for more than partial and underdeveloped explanations. But I do have one such primitive theory of value. As in the good Economics tradition, it has an air of the "never-never"; yet it is consistent with the observed conduct of certain trade, and it does suggest reasons for the responsiveness of customary values to supply/demand. The idea is addressed exclusively to partnership trade. The essence of it is that rates are set by social tact, notably by the diplomacy of economic good measure appropriate to a confrontation between comparative strangers. In a series of reciprocal exchanges the alternating appearance of this overbalance, first on the part of one partner then the other, would with hardly less certainty than open price competition establish an equilibrium rate. At the same time, the guiding principle of "generosity" should give the agreed rate some semblance of the equilibrium i.e., of supply/demand.

It has to be understood that trade between primitive communities or tribes is a most delicate, potentially a most explosive, undertaking. Anthropological accounts document the risks of trading ventures in foreign territory, the uneasiness and suspiciousness, the facility of a translation from trading goods to trading blows. "There is a link," as Levi-Strauss writes, "a continuity, between hostile relations and the provision of reciprocal prestations. Exchanges are peacefully resolved wars, and wars are the result of unsuccessful transactions" (1969, p. 67).15

15. " 'While trading, Indians won't hand a foreigner both the bow and the arrows at the same time' " (Goldschmidt, 1951, p. 336).

If primitive society succeeds by the gift and by the clan in reducing the state of Warre to an internal truce (see Chapter 4), it is only to displace outward, onto the relations between clans and tribes, the full burden of such a state. In the external sector the circumstances are radically Hobbesian, not only lacking that "common Power to keep them all in awe" but without even that common kinship that might incline them all to peace. In trade, moreover, the context of the confrontation is the acquisition of utilities; and the goods, as we have seen, may very well be urgent. When people meet who owe each other nothing yet presume to gain from each other something, peace of trade is the great uncertainty. In the absence of external guarantees, as of a Sovereign Power, peace must be otherwise secured: by extension of sociable relations to foreigners—thus, the trade-friendship or trade-kinship—and, most significantly, by the terms of exchange itself. The economic ratio is a diplomatic manoeuvre. "It requires a good deal of tact on the part of everyone concerned," as Radcliffe-Brown wrote of Andamanese interband exchange, "to avoid the unpleasantness that may arise if a man thinks that he has not received things as valuable as he has given. ..." (1948, p. 42). The people must come to terms. The rate of exchange takes on functions of a peace treaty.

Intergroup exchange does not simply answer to the "moral purpose" of making friends. But whatever the intent and however utilitarian, it will not do to make enemies. Every transaction, as we already know, is necessarily a social strategy: it has a coefficient of sociability demonstrated in its manner, and in its rates by the implied willingness to live and let live, the disposition to give full measure in return. As it happens, the safe and sane procedure is not just measure-for-measure, a reciprocity precisely balanced. The most tactful strategy is economic good measure, a generous return relative to what has been received, of which there can be no complaints. One remarks in these intergroup encounters a tendency to overreciprocate:

The object of the exchange [between people of different Andamanese bands] was to produce a friendly feeling between the two persons concerned, and unless it did this it failed of its purpose. It gave great scope for the exercise of tact and courtesy. No one was free to refuse a present that was offered to him. Each man and woman tried to out-do the others in generosity. There was a sort of amiable rivalry as to who could give away the greatest number of valuable presents [Radcliffe-Brown, 1948, p. 84; emphasis mine.]

The economic diplomacy of trade is "something extra" in return. Often it is "something for the road": the host outdoes his visiting friend, who made the initial presentation, a "solicitory gift" in token of friendship and the hope of safe conduct, and of course in the expectation of reciprocity. Over the long run accounts may balance, or rather one good turn begets another, but for the time being it is critical that some unrequited good measure has been thrown in. Literally a margin of safety, the exceeding generosity avoids at no great cost "the unpleasantness that may arise if a man thinks he has not received things as valuable as he has given," which is to say the unpleasantness that could be occasioned by cutting too fine. At the same time, the beneficiary of this generosity has been put under obligation: he is "one down"; so the donor has every right to expect equal good treatment the next time around, when he becomes the stranger and guest of his trade partner. On the widest view, as Alvin Gouldner has divined, these slight unbalances sustain the relation (Gouldner, 1960, p. 175).

The procedure of transitory unbalance, bringing generous returns from the home party to solicitory gifts, is not unique to the Andamans but in Melanesia rather common. It is the appropriate form between trade kinsmen of the Huon Gulf:

Kinship ties and bargaining are considered to be incompatible, and all goods are handed over as free gifts offered from motives of sentiment. Discussion of value is avoided, and the donor does the best he can to convey the impression that no thought of a counter gift has entered his head. . . . Most of the visitors ... go home with items at least as valuable as those with which they came. Indeed, the closer the kinship bond, the greater the host's generosity is, and some of them return a good deal richer. A careful count is kept, however, and the score is afterwards made even. (Hogbin, 1951, p. 84)

Or again, the Massim Kula:

The offering of the pari, of landing gifts by the visitors, returned by the talo'i, or farewell gifts from the hosts fall into the class ... of presents more or less equivalent. . . . The local man will as a rule [Malinowski seems to mean by this phrase "invariably"] contribute a bigger present, for the talo'i always exceeds the pari in quantity and value, and small presents are also given to the visitors during their stay. Of course, if in the pari there were included gifts of high value, like a stone blade or a good lime spoon, such solicitary gifts would always be returned in strictly equivalent form. The rest would be liberally exceeded in value (Malinowski 1922, p. 362)16

16. Cf. Malinowski, 1922, p. 188 on the unbalances in fish-yam exchange between partners of different Trobriand villages. For other examples of trade partner good measure in reciprocation see also Oliver, 1955, pp. 229, 546; Spencer, 1959, p. 169; cf. Goldschmidt, 1951, p. 335.

Suppose, then, this procedure of reciprocal good measure, as is actually characteristic of the Huon Gulf trade. A series of transactions in which the partners alternately manifest a certain generosity must stipulate by inference a ratio of equivalence between the goods exchanged. One arrives in due course at a fairly precise agreement on exchange values.

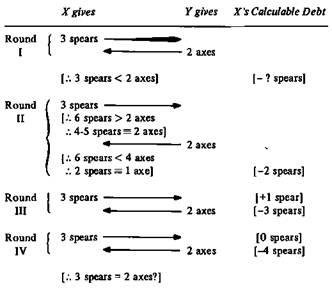

Table 6.2 presents a simple demonstration: two goods, axes and spheres, exchanged between two partners, X and Y, over a series of reciprocal visits beginning with X's visit and initial gift to Y After the first round, the two axes given by Fare understood generous in return for the three spears brought by X.

Table 6.2. Determination of exchange value through reciprocal good measure

At the end of the second round, in which Y first compounded X's indebtedness by two axes and was then himself indebted by X's gift of six spears, the implication is that nine spears exceed four axes in value. It follows at this juncture that seven to eight spears equals four axes, or taking into account the indivisibilities, a rate of 2 : 1 prevails. There is of course no necessity to continually escalate gifts. At the end of the second series, Y is down the equivalent of about one spear. Should X bring one to three spears the next time and Y reciprocate one to three (or better, two or three) axes, a fair average balance is maintained. Note also that the rate is something each party mechanically agrees upon, insofar as each understands the current balance of credit and indebtedness, and if any serious misunderstanding does arise the partnership breaks down— which likewise stipulates the rate at which trade must proceed.

Considering the comparisons (perhaps invidious) of trade returns likely to be made with fellows of one's own side, these understandings of equivalence stand a chance of becoming common understandings. Comparison of trade returns are the nearest thing to implicit internal competition I am able to construe. Presumably, information thus gained might be applied next time against one's trade partner of the other community. There seems to be very little evidence on this point, however, or on just how precise is the available information of compatriots' dealings—in some instances transactions with outside partners are conducted privately and rather furtively (Harding, 1967).

The example before us is specifically a simple model case, supposing reciprocal visiting and a standard presentation procedure. It is conceivable that different trade arrangements have some other calculus of exchange value. If, for instance, X of the simple model was a trader-voyager, always on the visiting side, and if the same etiquette of generosity held, the actual ratio would probably favor X's spears more, insofar as Y would be repeatedly obliged to be magnaminous. Indeed, if X consistently presented three spears, and Y consistently returned two axes, the same ratio could be maintained for four rounds without X being down after his initial gift, even though a rate of approximately 2 : 1 is calculable midway through the second round (Table 6.3).

Table 6,3. Rate determination: one-way visiting

A 3 : 2 customary rate could in that event develop. Either way there are obvious advantages to the voyaging group—though they must bear all the transport, so that the gains over the rate for reciprocal visiting will parallel "supply-cost" differences.

This second example is only one of many possible permutations of exchange rate determination. Even in one-way voyaging, the etiquette of presentation and counterpresentation may be more complicated than that supposed (for example, Barton, 1910). I bring the example forward merely to suggest the possibility that different formalities of exchange generate different exchange rates.

No matter how complex the strategy of reciprocity by which an equilibrium is finally determined, and however subtle our analysis, it remains to be known exactly what has been determined economically. How can it be that a rate fixed by reciprocal generosity expresses the current average supply and demand? Everything depends on the meaning and practice of that capital principle, "generosity." But the meaning is ethnographically uncertain, and therein lies the major weakness of our theory. Only these few facts, not celebrated either for their repetition in the documents, are known: that those who bring a certain good to the exchange are related to it primarily in terms of labor value, the real effort required to produce it, while those to whom the good is tendered appreciate it primarily as a use value. That much we know from incidents to the Huon Gulf and Siassi trade, wherein the labor of manufacture was exaggerated by the suppliers but the product thereof depreciated by the takers—both sides in hopes of influencing terms of trade in their own favor (see above). From this steadfast devotion to the main chance, one has to work back by a kind of inverted logic to the possible meaning of "generosity." Supposing the necessity of reciprocal good measure, it would follow that each party has to consider, in addition to the virtues of the goods he receives, the relative utility to the other party of the goods he gives, and in addition to the labor he has expended himself, the work also of the other. "Generosity" has to bring use value into relation with use value, and labor with labor.

If so, "generosity" will bring to bear on the rate of exchange some of the same forces, operating in the same direction, as affect price in the marketplace. In principle, goods of higher real cost will evoke higher returns. In principle too, if goods of greater utility oblige the recipient to greater generosity, it is as much as saying that price is disposed to increase with demand.17

17. Further, it appears the empirical case that a discrepancy in labor values can be sustained by an equivalence in utilities (cf. Godelier, 1969). "Need" is matched to "need," perhaps at the real expense of one party—although, as we have seen, the norm of equal work may still be maintained by ideological ruse and pretense. This kind of discrepancy would be most likely where the goods traded belong to different spheres of exchange within one or both trading communities, for example, manufactured goods for food, especially where the craft goods are used also in such as bridewealth payments. Then the high social utility of a small amount of one good (the manufactured good) is compensated by a large quantity of the item of lesser status. This may be an important secret in the "exploitation" of richer areas by poorer (e.g., Siassi).

Thus compensating efforts to the producer and utilities to the receiver, the rates set by tactful diplomacy will express many of the elemental conditions that are resumed otherwise in the economist's supply curves and demand curves. Into both would enter, and to the same general effects, the real difficulties of production, natural scarcities, the social uses of goods, and the possibilities of substitution. In many respects the opposite of market competition, the etiquette of primitive trade may conduct by a different route to a similar result. But then, there is from the beginning a basic similarity: the two systems share the premise that the trader should be satisfied materially, the difference being that in the one this is left solely to his own inclination while in the other it becomes the responsibility of his partner. To be a diplomatically satisfactory "price" however, the price of peace, the customary exchange ratio of primitive trade should approximate the normal market price. As the mechanisms differ, this correspondence can only be approximate, but the tendency is one,

Date: 2014-12-21; view: 1400

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| The Social Organization of Primitive and Market Trade | | | Stability and Fluctuation of Exchange Rates |