CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Exchange Value and the Diplomacy of Primitive Trade

Anthropological economics can respectably claim one theory of value on its own, fashioned from empirical encounters in its own province of primitive and peasant economies. Here, in many of the societies, have been discovered "spheres of exchange" which stipulate for different categories of goods differential standing in a moral hierarchy of virtu. This is anything but a theory of exchange value. The diverse values put on things depend specifically on barriers to their interchange, on the inconvertibility of goods from different spheres; and as for the transactions ("conveyances") within any one sphere, no determinants of the rates have yet been specified (cf. Firth, 1965; Bohannan and Dalton,1962; Salisbury, 1962). So ours is a theory of value in nonexchange, or of nonexchange value, which may be as appropriate to an economy not run on sound business principles as it is paradoxical from a market standpoint. Still it is plain that anthropological economics will have to complete its theory of value with a theory of exchange value, or else abandon the field at this juncture to the forces of business as usual: supply, demand, and equilibrium price. This essay constitutes a reconnaissance with a view toward defending the terrain as anthropological territory. But it will be in every sense a venture in "Stone Age Economics"—and rather of the earlier phase than the later. Its intellectual weapons are the crudest choppers, capable only of indelicate blows at the objective, and likely soon to crumble against refactory empirical materials.1

1.1 do not attempt here a general theory of value. The principal concern is exchange value. By the "exchange value" of a good (A), I mean the quantity of other goods (B, C, etc.) received in return for it—as in the famous couplet "The value of a thing/Is just as much as it will bring." For the historical economies in question, it remains to be seen whether this "exchange value" approximates the Ricardian-Marxist "value," the average social labor embodied in the product. Were it not for the ambiguity introduced by spheres of exchange in assigning goods different relative standing, the term "relative value" might be more acceptable all around than "exchange value"; where the context allows, I substitute the former term. "Price" is reserved for exchange value expressed in money terms.

For the facts are difficult. True they are often disconcerting from the orthodox vantage of supply and demand and generally remain so even if, in the absence of price-fixing markets, one agrees to meanings of "supply" and "demand" more relevant than the current technical definitions (that is, the quantities that would be made available and taken up over a series of prices). The same facts, however, are just as perturbing to anthropological convictions, such as those that begin from the prevalence in the primitive economies of "reciprocity," whatever that means. Indeed, the facts are perturbing precisely because we rarely bother to say what it does mean, as a rate of exchange.

But then, a "reciprocity" that comprehends precise material rates is rarely encountered. The characteristic fact of primitive exchange is indeterminancy of the rates. In different transactions, similar goods move against each other in different proportions—especially so in the ensemble of ordinary transactions, the everyday gift giving and mutual aid, and in the internal economy of kinship groups and communities. The goods may be deemed comparable to all intents by the people involved, and the variation in rates occur within the same general time period, place, and set of economic conditions. In other words, the usual stipulations of market imperfection seem not to blame.

Nor is the variability of reciprocity attributable to that supreme imperfection, higgle-haggle, where an interconnection between different deals is lacking and competition reduced to its ultimate term of an oriental confrontation between buyer and seller. Although it would account theoretically for the indeterminancy, bargaining is too marginal a strategy in the primitive world to bear the burden of a general explanation. To most primitive peoples it is completely unknown; among the rest, it is mostly an episodic relation with strangers.

(If I may be allowed here an impertinent aside, in no way justified by an impressive personal ignorance of Economics, the ready supposition of extreme circumstances, amounting to the theoretical null or limiting case, seems nevertheless characteristic of attempts to apply the formal business apparatus to primitive economies: demand with the substitution potential and elasticity of a market for food in a beleaguered city, the supply sensitivity of a fish market in the late afternoon—not to mention the appreciation of mother's milk as "enterprise capital" [Goodfellow, 1939] or the tautological dispensation of failures to take the main chance by invocation of a local preference for social over material values. It is as if primitive peoples somehow manage to construct a systematic economy under those theoretically marginal conditions where, in the formal model, system fails.)

In truth, the primitive economies seem to defy systematization. It is practically impossible to deduce standard going rates from any corpus of transactions as ethnographically recorded (cf. Driberg, 1962,p. 94; Harding, 1967; Pospisil, 1963; Price, 1962, p. 25; Sahlins, 1962). The ethnographer may conclude that the people put no fixed values on their goods. And even if a table of equivalences is elicited— by whatever dubious means—actual exchanges often depart radically from these standards, tending however to approximate them most in socially peripheral dealings, as between members of different communities or tribes, while swinging wildly up and down in a broad internal sector where considerations of kinship distance, rank, and relative affluence are effectively in play. This last qualification is important: the material balance of reciprocity is subject to the social sector. Our analysis of exchange value thus begins where the last chapter, on "the sociology of primitive exchange," left off.

The discussion in Chapter 5 argued at length the social organization of material terms. To recapitulate very briefly: from one vantage, the tribal plan presents itself as a series of concentric spheres, beginning in the close-knit inner circles of homestead and hamlet, extending thence to wider and more diffuse zones of regional and tribal solidarity, to fade into the outer darkness of an intertribal arena. This is at once a social and moral design of the tribal universe, specifying norms of conduct for each sphere as are appropriate to the degree of common interest. Exchange too is moral conduct and is so regulated. Hence, reciprocity is generalized in the innermost sectors: the return of a gift only indefinitely prescribed, the time and amount of reciprocation left contingent on the future needs of the original donor and abilities of the recipient; so the flow of goods may be unbalanced, or even one-way, for a very long period. But on leaving these internal spheres and uncertain repayments, one discovers a sector of social relations so tenuous they can only be sustained by an exchange at once more immediate and balanced. In the interest of a long-term trade, and under the social protection of such devices as "trade partnership," this zone may even extend to intertribal relations. Beyond the internal economy of variable reciprocity is a sphere, of greater or less expanse, marked by some correlation between the customary and de facto rates of equivalence. Here, then, is the area of greatest promise to research on exchange rates.

In the same way as the origin of money has traditionally been sought in external markets, and for many of the same reasons, the quest for a primitive theory of value turns to exterior spheres of transaction. Not only is balanced dealing there enjoined, but the exchange circuits of the internal economy tend to disintegrate and combine, as the immorality of "conversion" is rendered irrelevant by social distance. Goods that were separated from each other inside the community are here brought into equivalence. Attention especially should be directed to transactions between trade friends and trade kinsmen, for these relationships stipulate economic equity and going rates. Accordingly, the inquiry that follows shall concentrate upon partnership trade, and, out of practical considerations, upon a few empirical cases only, chosen however from areas of the Pacific famous for an indigenous commerce.

Three Systems of Trade

We shall examine three areal exchange networks, constituting besides three different structural and ecological forms: the Vitiaz Straits and Huon Gulf systems of New Guinea, and the intertribal trade chain of northern Queensland, Australia. In each case a certain play of supply /demand is detectable in the rates of exchange. Yet the existence of this supply/demand influence renders the trade even less comprehensible than would its absence. For the kind of market competition that alone in economic theory gives supply and demand such power over exchange value is completely absent from the trade in question.

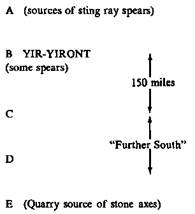

The essentials of the Queensland network are exhibited in Figure 6.1 (constructed after the brief description provided by Sharp, 1952). In structure it is a simple chain of trade, band linked to band along a line running approximately 400 miles south from the Cape York coast. Each group is limited to contacts with its immediate neighbors, thus only indirectly related to bands further along the line. The trade itself proceeds in the form of gift exchange between elders standing as classificatory brothers. Working out of Yir-Yoront, Sharp could give few details of the axe-spear exchange running the length of the chain, but the information is sufficient to document the effect of supply/demand on the terms of transaction. This by the simple principle that if, in an areal network, the exchange rate of a good (A) in terms of another (B) rises in proportion to distance from the source of A, it is reasonable to suppose that the relative value of A is increasing pari passu with "real" costs and scarcities, that is, with declining supply, and probably also with increasing demand. The differences in spear-axe exchange ratios along the Queensland chain would reflect the double play of this principle. At Yir-Yiront, near the northern source of spears, 12 of them must be given for a single axe; about 150 miles south, that much closer to the source of axes, the rate falls to one to one; in the extreme south the terms (apparently) become one spear for "several" axes. A point then for supply and demand, and apparently for orthodox Economic Theory.

A. Trading Groups

B. Rates of exchange at various points

at B YIR-YIRONT, 12 Spears = 1 Axe

C 1 spear = 1 Axe

D 1 Spear = "Several Axes*' (presumably)

Figure 6.1. Queensland Trade Chain (after Sharp, 1952)

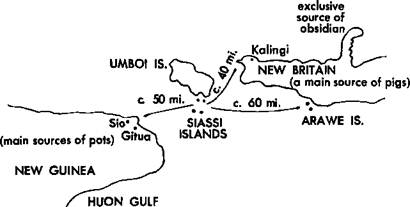

The trade system of the Vitiaz Straits arrives at the same effect but by different organizational means (Figure 6.2).

A. Section of the Siassi Trade Sphere.

B. Some Transactional Sequences of Siassi Middlemen.

Figure 6.2. Middleman Gains of Siassi Traders (from Harding, 1967)

Articulated from the center by the voyages of Siassi Islanders, the Vitiaz network is but one of several similar circles established in Melanesia under the aegis of Phoeneican-Iike middlemen. In their own areas, the Langalanga of Malaita, the Tami Islanders, the Arawe of New Britain, the Manus of the Admiralties and the Bilibili of New Guinea ply a similar trade. This mercantile adaptation merits a short comment.

The trading groups are themselves marginally if centrally situated, often perched precariously on stilt-house platforms in the middle of some lagoon, without a mow of arable land to call their own or any other resources save what the sea affords them—lacking even wood for their canoes or fibers for their fishnets. Their technical means of production and exchange are imported, let alone their main stocks in trade. Yet the traders are typically the richest people of their area. The Siassi occupy about one three-hundredths of the land in the Umboi subdistrict (which includes the large island of that name), but they make up approximately one quarter of the population (Harding, 1967, p. 119).2

2. "The Manus . . . most disadvantageous^ placed of all the tribes in that part of the archipelago, are nevertheless the richest and have the highest standard of living" (Mead, 1937, p. 212).

This prosperity is the dividend of trade, amassed from a number of surrounding villages and islands, themselves better endowed by nature but tempted to commerce with the Siassi for reasons ranging from material to marital utility. The Siassi regularly exchanged fish for root crops with adjacent villages of Umboi Island; they were the sole suppliers of pottery for many people of the Vitiaz region, transhipping it from the few places of manufacture in northern New Guinea. In the same way they controlled the distribution of obsidian from its place of origin in northern New Britain. But at least equally important, the Siassi constituted for their trade partners a rare or exclusive source of bridewealth and prestige goods—such items as curved pigs' tusks, dogs' teeth, and wooden bowls. A man in neighboring areas of New Guinea, New Britain, or Umboi could not take a wife without some trade beforehand, direct or indirect, with the Siassi. The total consequence of Siassi enterprise, then, is a trade system of specific ecological form: a circle of communities linked by the voyages of a centrally located group, itself naturally impoverished but enjoying on balance an inward flow of wealth from the richer circumference. This ecological pattern depends upon, is the precipitate of certain arrangements on the plane, of exchange. Although the domains of different trading peoples sometimes overlap, a group such as Siassi fairly monopolizes carrying within its own sphere. There the "competition" is dramatically imperfect: the several and far-flung villages of the circumference are without direct intercourse with one another. (The Manus went so far as to prevent other peoples of their orbit from owning or operating seagoing canoes [cf. Mead, 1961, p. 210]). Capitalizing on the lack of communication between distant communities, and with an eye always toward enhancing the rates of exchange, the Siassi during traditional times were pleased to spread fantastic tales about the origins of goods they transmitted:

. . . cooking pots are distributed from three widely-separated locations on the mainland [New Guinea]. No pottery in manufactured in the archipelago [that is, Umboi, nearby islands, and western New Britain], and people there who receive pots via the Siassis (and earlier the Tamis) previously were not even aware that clay-pots were man-made products. Rather, they were regarded as exotic products of the sea. Whether the non-pottery peoples originated this belief is uncertain. The Siassis, however, elaborated and helped to sustain such beliefs, as everyone since has learned. Their story was that the pots are the shells of deep-water mussels. The Sios [of New Guinea] make a specialty of diving for these mussels and, after eating the flesh, sell the empty "shells" to the Siassi. The deception, if it added to their value, was justified by the vital part that pots have in overseas trade (Harding, 1967, pp. 139-140).

By my understanding (based on a brief visit) the Siassi in these tales were exaggerating more directly the effort of production than the scarcity of the pots, on the local principle that "big-fella work" is worth "big-fella pay." The most advanced mercantile guile was imbricated in a most innocent labor theory of value. It is only consistent that the customary partnership of the Vitiaz network, a kind of trade-friendship (pren, N-M), is several degrees removed in sociability from the trade-kinship of the Queensland system. True, the exchanges between Siassi and their partners followed standard rates. But, secure in their middlemen position and indispensable to their "friends," towards whom they were not profoundly compelled to be considerate, the Siassi in the context of these rates were charging what the traffic would bear. Exchange values not only varied locally with supply/ demand—judging again by the difference in terms according to distance from origin (Harding, 1967, p. 42 passim)—but monopolistic sharp practice may have afforded discriminatory gains. As the transactional sequences show (Figure 6.2), the Siassi, by voyaging here and there, could in principle turn a dozen coconuts into a pig, or that one pig again into five. An extraordinary tour of primitive passe-passe— and another apparent victory for the businesslike interpretation of indigenous trade.3

3. Local demand in the Manus trade system is indicated by an unusual device. In Manus transactions with Balowan, where sago is scarce, one package of sago offered by Manus will bring ten mud hen's eggs from Balowan; but the equivalent of a package of sago offered by Manus to Balowan in shell money commands only three mud hen's eggs. (Clearly if the Manus anywhere can convert these several items they make a killing.) Similarly, in Manus daily trade with Usiai land people, demand is indicated by unequal ratios of the following sort: one fish from Manus-ten taro or forty betel nut from Usiai; whereas one cup of lime from Manus-four taro or eighty betel nut from Usiai. Mead comments: "Betel-chewing need is matched against betel chewing need, to coerce the sea people [Manus] into providing limefor the land peoples" (Mead, 1930, p. 130). That is to say, when the Usiai want lime, they offer betel nut, as the Manus can realize more betel in exchange for lime than for fish; if Usiai wanted fish, they would have brought taro. On the labor advantage to Manus in this trade, and the gains appreciated through supply/demand variations in different parts of the Manus network, see Schwartz, 1963, pp. 75, 78.

The same confidence in the received economic wisdom is not as readily afforded by the Huon Gulf system, for here goods of specialized local manufacture are transacted at uniform rates throughout the network (Hogbin, 1951). Nevertheless, a simple analysis will show that supply and demand are once more at work.

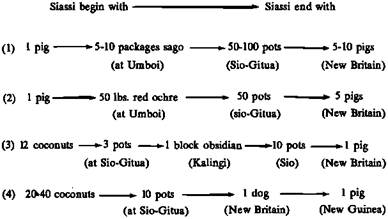

The semicircular coastal network of the Gulf again unites ethnically heterogeneous communities (Figure 6.3). Trade, however, is effected through reciprocal voyaging: people of a given village visit and in turn are visited by partners from several other places, both up and down the coast, although usually from the nearer rather than the more distant vicinity. The trade partners are kinsmen, their families linked by previous intermarriage; their commerce accordingly is a sociable gift exchange, balanced at traditional rates. Certain of these rates are indicated in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1. Customary equivalents in trade, Huon Gulf trade network (data from Hogbin, 1951, pp. 81-95)

| I. Busama | |

| For | Busama gives |

| 1 large pot | = c. 150 pounds taro or 60 pounds sago |

| 24-30 large pots | = 1 small canoe |

| 1 small pot | = c. 50 pounds taro or 20 pounds sago |

| 1 mat | = 1 small pot |

| 3 mats | = 1 large pot (or 2 shillings)* |

| 4 purses | - 1 small pot (or 1 shilling for 2) |

| 1 basket | = 2 large bowls (or one pound) |

| 1 bowl (usual size) | = 10-12 shillings (more for larger bowls) |

| II. North Coast Villages | |

| For | North Coast villages give |

| 1 large pot | = 4 string bags or 3 mats (or 6-8 shillings) |

| 1 small pot | = 1 mat (or 2 shillings) |

| 4 purses | = 1 mat (or 1 shilling for 2) |

| 1 basket | = 10 mats (or one pound) |

| 1 carved bowl | = food, unknown quantity |

| III. Labu | |

| For | Labu gives |

| 2 large pots | 1 woven basket (or 6-8 shillings) |

| 1 small pot | = 4 purses (or 2 shillings) |

| 1 string bag | = 3 purses (or 2 shillings) |

| 1 carved bowl | = 10-12 shillings |

| IV Pottery villages | |

| For | Pottery villages give |

| 150 pounds taio or 60 pounds sago | 1 large pot |

| 50 pounds taro or 20 pounds sago | = 1 small pot |

| 4 string bags | = 1 large pot |

| 1 mat | 1 small pot |

| 3 mats | = 1 large pot |

| 4 purses | = 1 small pot |

| 1 basket | 2 large pots |

| 1 carved bowl | = 8 shillings |

| 1 small canoe | = 24-30 pots |

♦Except in exchange for bowls, money was rarely used in the trade at the time of study.

Local specialization in craft and food production within the system is attributed by Hogbin to natural variations in resource distribution. A single village or small group of adjacent villages has its characteristic specialty. Since voyaging ranges are limited, centrally situated communities act as middlemen in the transmission of specialized goods produced towards the extremities of the Gulf. The Busama, for instance, from whose vantage the trade was studied, send southward the mats, bowls, and other goods manufactured on the north coast, and send northward the pots made in the southern villages.

Like other New Guinea trade networks, the Huon system was not entirely closed. Each coastal village had truck with peoples of its own immediate hinterland. Moreover theTami Islanders, themselves longdistance voyagers, connected the Huon on the north with the Siassi sphere; in traditional times the Tami disseminated within the Gulf obsidian that had originated in New Britain. (Potters in the southern villages likewise exported their craft further south, although little is known about this trade.) A question is thus presented: Why isolate the Huon Gulf as a distinct "system"? There is a double justification. First, on the material plane the several villages apparently comprise an organic community, retaining within their own sphere the great majority of locally produced goods. Secondly, on the organizational level, this kinship trade of a determinate form, and evidently also the uniform series of exchange rates, seem to be restricted to the Gulf.4

4. I cannot however verify these assertions; in the event they prove invalid certain suggestions of the following paragraphs will require modification.

Figure 6.3. Huon Gulf Trade Network (from Hogbin, 1951)

For those inclined to belittle the practical (or "economic") significance of primitive trade, the Huon Gulf network affords a salutory antidote. Certain villages would not have been able to exist as constituted in the absence of trade. In the meridional reaches of the Gulf, cultivation encounters natural difficulties, and sago and taro have to be obtained from the Buakap and Busama districts (see Figure 6.3 and Table 6.1). "Without trade, indeed, the southern peoples [the pottery makers] could not long survive in their present environment" (Hog-bin, 1951, p. 94). Likewise, the soil available to the Tami Islanders of the northeast is inadequate: "Much of [their] food has to be imported" (p. 82). In the event, food exports from fertile areas such as Busama comprise an important fraction of local production: taro "upwards of five tons monthly" is sent out of the community, principally to four southern villages; whereas Busama themselves consume 28 tons monthly (direct human subsistence). By the ample dietary standards prevailing at Busama (p. 69) the taro exported could feed another community of 84 people. (The average village population along the Gulf is 200-300; Busama, with more than 600 people, is exceptionally large.) Globally, then, the Huon Gulf presents an ecological pattern precisely the opposite of the Vitiaz Straits: the peripheral communities are here naturally poor, the center rich, and there is on balance a strategic flow of wealth from the latter to the former.

Allowing certain surmises, the dimensions of this flow can be read from the exchange ratios of central to peripheral goods. Busama taro, for example, is traded against southern pottery at a rate of 50 pounds of taro to one small pot or 150 pounds to one large pot. Based on a modest personal acquaintance with the general area, I judge this rate very favorable to pots in terms of necessary labor time. Hogbin seems to hold the same opinion (p. 85). In this connection, Douglas Oliver observed of southern Bougainville, where one "medium-sized" pot is valued at the same shell money rate as 51 pounds of taro, that the latter "represents an incomparably larger amount of labor" (1949, p. 94). In terms of effort, the equations of the Busama-pottery village trade appear to be unbalanced. By the rates prevailing, the poorer communities are appropriating to their own existence the intensified labor of the richer.

Nevertheless, this exploitation is veiled by a disingenuous equation of labor values. Although it appears to fool no one, the deception does give a semblance of equity to the exchange. The potters exaggerate the (labor) value of their product, while the Busama complain merely of its use value:

Although etiquette prevents argument, I was interested to observe when accompanying some Busama on a trading journey southwards how the Buso [pottery] villagers kept exaggerating the labour involved in pot making. "We toil all day long at it from sunrise to sunset," one man told us over and over again. "Extracting the clay is worse than gold mining. How my back aches! There's always the chance, too, that in the end the pot will develop a crack." The members of our [Busama] party murmured polite agreement but subsequently brought the conversation round to the inferior quality of present-day pots. They confined themselves to generalitites, accusing no one in particular, but it was apparent that here was an attempt at retaliation (Hogbin, 1951, p. 85).

Rates of exchange are, as noted, fairly uniform throughout the Gulf. In any of the villages, for instance, where mats, "purses" and/or pots are customarily exchanged, one mat-four purses=one small pot. These rates hold regardless of distance from the point of production: a small pot is valued at one mat either in the southern villages where pottery is made or on the north coast where mats are made. The direct implication, that centrally situated middlemen take no gains in the turnover of peripheral goods, is affirmed by Hogbin. There are no "profits" to Busama in transferring southern pots to the north or northern mats to the south (Hogbin, 1951) p. 83).

The simple principle posed to detect supply-demand influences in the Vitiaz and Queensland systems, where exchange values varied directly by distance from the site of production, is therefore not applicable to the Huon Gulf. But then the shape of the Huon "market" is different. Technically it is less imperfect. Potentially at least, a given community has more than one supplier of a given good, so that those tempted to exact special gains run the risk of being bypassed. Hence the Busama rationalization of their failure to take middlemen tolls: "Each community needs the products of all the rest, and the natives freely admit their willingness to sacrifice economic gain to keep within the exchange ring." (p. 83). All this does preclude the possibility of supply/demand effects on exchange rates. The possibility is transposed rather to the higher level of the network as a whole. It becomes a question of whether the relative value of one good in terms of another reflects the respective aggregate supply/demand throughout the Gulf.

A remarkable exception to uniform rates, amounting it would seem to a violation of the most elementary principles of good business and common sense, suggests this is exactly the case. The Busama pay 10-12 shillings for Tami Islander bowls and exchange them in the southern villages for pots worth eight shillings.5

5 Cash has particularly replaced the pigs' tusks traditionally traded for Tami bowls, corresponding to a replacement of the latter by European currency in the brideprices of the Finschhafen area.

In explanation the Busama say of the southern potters: " 'They live in such hungry country. Besides we want pots for use for ourselves and to exchange for mats and things' " (Hogbin, 1951, p. 92). Now, the explanation in terms of pots contains an interesting implication in terms of the taro which the Busama themselves produce. The Busama clearly suffer penalties in their southern trade because of the limited demand for taro throughout the Gulf, especially on the part of the northern villages, where a variety of craft goods are produced. The "market" for taro is effectively restricted to the southern potters. (In Hogbin's exchange table [Table 6.1] taro is noted only in the southern trade; reference to taro disappears from the description of northern trade.) But if Busama taro has little exchangeability, the pots manufactured exclusively in the south are everywhere in demand. More than an item of consumption, these pots become for Busama a capital item of trade, without which they would be cut off to the north, so for which they are willing to pay dearly in labor costs. Thus the classic business forces are in play in this sense: the relative value of Busama taro in terms of southern pots represents the respective demands for these goods in the Huon Gulf as a whole.6

6. Belshaw reports a trade system in the southern Massim apparently similar in exchange value conditions to the Huon Gulf (1955, pp. 28-29, 81-82). He notes, however, that rates of certain items—areca nuts, pots, and stick tobacco—do vary locally with demand. I may not fully understand his argument, which is phrased in shilling equivalents, but what it seems to show, when taken in conjunction with the published table of exchange ratios (pp. 82-83), is that values of these goods in terms of each other reflect respective supply and demand in the southern Massim as a whole, not that their exchange values vary locally from place to place (except perhaps in modern shilling deals). A particular good would command more or less of another, depending on the global supply/demand, but whatever the ratio in one place it is the same in another. The published tables seem to indicate fairly uniform customary exchange rates:.for example, one pot is traded for one "bunch" or one "bundle" of areca nuts at several locations (Tubetube, Bwasilake, Milne Bay), whereas two sticks of tobacco are given for one "bunch" of areca at Sudest and one pot for two sticks of tobacco at Sumarai (pp. 81-82).

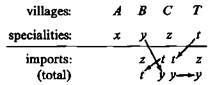

The point may be made in a more abstract way. Suppose three villages, A and B and C, each the producer of a special good, x, y, and z respectively, and linked in a chain of trade such that A exchanges with B and B again with C. Consider then the exchange of x against y between villages A and B:

Villages: A B C

goods: x y z

Assuming none of these products superabundant, the quantity of y surrendered by B to obtain x will depend in part on the demand for y as compared to x in village C. If in village C the demand for x is much greater than demand for y, then B, with a view toward the eventual acquisition of z, is willing to pay more dearly in y to obtain x from A. Conversely, if in C the demand for y greatly outweighs x, then B will tend to hold back y in the exchange with village A. Thus the rate on the exchange of local products between any two villages would summarize the demands of all villages in the system.

I open a long parenthesis. Although the analysis is justifiably broken off at this point, with the understanding that Huon Gulf exchange values respond to ordinary market forces, one is tempted nevertheless to press the issue further, into a domain at once more speculative and more real, wherein is discovered not only a certain confirmation of the thesis but insights into the ecology, the structural limits and the history of such a system.

In the key example that unlocked the above analysis, the Busama were content to absorb a net loss on Tami bowls, hoping that way to encourage the flow of pottery from the south. As it was but one exchange in an interdependent sequence, the transaction proved unintelligible in itself. The three-village model facilitated understanding, but still it could not adequately represent all the constraints finally materialized in the sale of the bowl. For behind this transaction lay a whole series of preliminary exchanges by which Tami bowls were carried from place to place around the Gulf, effecting in the process a large preliminary redistribution of local specialities. It is in the hope of specifying this redistribution, and the material pressures developing therefrom, that further speculation is hazarded.

A four-village model is now required. To ease the re-entry into reality, we can retain the original three (A, B, and C), while identifying B as Busama and A then as the potters, and adding a fourth village, T, to represent Tami with its specialized product, t (bowls). Suppose, too, although it is not exactly the case, that the export goods of each community are liberally demanded by all the others; and that, more nearly true, each community exchanges only with the village or villages directly contiguous. The objective of the exercise will be to pass Tami bowls (t) from one end of the sequence to the other, determining thus the total distribution of specialized products that would result.

In the hope of explaining better that notable sale of Tami bowls by Busama to the potters (A), the exchanges first will be played out a trois between villages B (Busama), C.and ^(Tami). By the initial moves then, 7* and C exchange their respective items, t and z, and villages

B and C theirs, y and z. Leaving aside the question of quantities traded, the types of goods would, after this first round, assume the following distribution:

The second round, designed to carry an amount of t, bowls, to community B (and of y to T) already presents certain difficulties—not insurmountable yet symptomatic of the pressures accumulating within the system, and of its destiny. Under the given conditions, however, there is little choice. Village C is unlikely to accept z from B in exchange for t, since C already produces z; hence, B can only again offer y to C to acquire t, at that probably but part of the t in Cfe possession. In the same way T passes more tto Cto obtain y. This done, the three-village chain is completed: goods from one terminus {A still excluded) appear at the other.

Completed—but perhaps also finished. At this juncture, 2?(usama) finds herself in an embarrassing relation to the global distribution of specialities and imports, her possibilities of further trade drastically reduced. B (usama) has nothing to put into circulation that villages down the line, Cand T, do not already have, and have probably in quantities proportional to their proximity to B. Hence the strategic importance of village A, the potters, to Busama. Busama's continued participation in the exchange network hinges now on escaping from it, on opening a trade with A, which is also to say that the continuity of the trade system as a whole depends on its expansion. And in this strategic overture, the pottery of A must present itself to B not only as a use value but as the only good enjoying exchangeability for the goods of C.,. T. The transaction between 5 and A masses and brings to bear against the pottery of A the weight of all the other goods already in the system. Hence the exchange rates unfavorable to the goods of B (usama) and the losses taken in labor "costs."

May one read from an abstract model to an unknown history? Composed in the beginning of a few communities, a trade system of the Huon type would soon know a strong inclination to expand, diversifying its products in circulation by extending its range in space. Peripheral communities in particular, their bargaining position undermined during the initial stages of trade, are impelled to search further afield for novel items-in-trade. The network propogates itself at its extremities by a simple extension of reciprocity, coupling in new and, it is reasonably argued, by preference exotic communities, those that can supply exotic goods.

(The hypothesis may for other reasons be attractive to students of Melanesian society. Confronted by extensive trade chains such as the kula, anthropologists have been inclined at once to laud the complexity of the "areal integration" and wonder how it could possibly have come about. The merit uf the dynamic outlined is that it makes a simple segmentary accretion of trade—of which Melanesian communities are perfectly capable—also an organic complication.)

But an expansion so organized must eventually determine its own limits. The incorporation of outside communities is achieved only at a considerable expense to villages at the frontiers of the original system. Transmitting the demand already occasioned by the internal redistribution of local specialities, these peripheral villages develop outside contacts on terms greatly disadvantageous to themselves in labor costs. The process of expansion thereby defines an ecological perimeter. It can continue passably enough through regions of high productivity, but once having breached a marginal ecological zone its further advance becomes unfeasible. Communities of the marginal zone may be only too happy to enter the system on the favorable terms offered them, but they are themselves in no position to support the costs of further expansion. Not that they, become now the peripheral outposts of the network, cannot entertain any trade beyond. Only that the trade system as organized, as an interrelated flow of goods governed by uniform procedures and rates, here discovers a natural boundary. Goods that pass beyond this limit must do so under other forms and rates of exchange; they pass into another system.7

7. Thus Huon Gulf goods may well pass through Tami into the Siassi-New Britain area, but probably under different trade terms, for the Tami islanders act as middlemen in a part of this area, very like the Siassi and probably also to some net advantage.

Deduction thus rejoins reality. The ecological structure of the Huon system is exactly as stipulated theoretically: relatively rich villages in the central positions, relatively poor villages at the extremes, and by the terms of trade a current of value and strategic goods moving from central to marginal locations. End of parenthesis.

Summarizing to this juncture, in the three Oceanic trade systems under review, exchange-values are responsive to supply and demand—at least insofar as supply and demand are inferable from the real distribution of the goods in circulation. Business as usual.

Rate Variations over Time

Furthermore, the evidence so far reviewed, in the main spatially derived, can be supplemented by observations taken over time at specific Melanesian trade sites. Temporal variations of exchange value follow the same iron laws—with one reservation: the rates tend to remain stable in the short run, unaffected by even important changes in supply and demand, although they do adjust in the long run.

Seasonal fluctuations of supply, for example, generally leave the terms of trade untouched. Salisbury suggests of the Tolai (New Britain) inland-coastal exchange that it could not otherwise be managed:

The net movement of tabu [shell money] from inland to coast, and vice-versa, is small. This conflicts with the impression one gets at different seasons, that all coastals are buying taro and not earning any tabu, or that inlanders are buying up all the fish for ceremonials and not selling much taro. If prices were fixed by current supply-demand ratios, they could vary widely and unpredictably. It is in just such a context that a trade in fixed equivalences is highly desirable, with the "traditional" prices being those that provide an equal balance over the long term. (Salisbury, 1966, p. 117 n.)

Over a quite long term, however, "traditional" Tolai equivalencies do vary. Exchange rates for food in 1880 were only 50-70 percent of the 1961 rates. Apart from some overall growth in shell-money stocks, the dynamics of this change are not altogether clear. But elsewhere in Melanesia, long-term revisions in exchange value have clearly ensued from the increased supplies of goods (and even shell monies) pumped into local trade systems by Europeans. An observation from Kapauku illustrates both tendencies here at issue, the short-run sluggishness8 of customary rates—although Kapauku are not famous for their fair trading—and a long-run sensitivity:

In general, however, the fluctuation of price because of temporary imbalance of the supply-demand level is rather infrequent . . . [But] a steady increase of supply may bring about a steady decline of the actual price. The permanence of this state has an effect upon the customary price which tends to be identified with the actual payments. Thus, before 1945, when iron axes had to be brought from the coastal people, the customary price was lOKm for an axe. The coming of the white man and the resulting increase and direct supply of axes, reduced the old price to half the former amount The process is still going on and the actual price in 1956 tended to fall below the customary price of 5Km per axe (Pospisil, 1958, pp. 122-123; cf. Dubbeldam, 1964).

By 1959 an axe could be had for only two units of native currency (2Km) (Pospisil, 1963, p. 310). Still, the Kapauku example is extraordinary, since the economy includes a large sector of bargained exchange where going rates may vary radically from transaction to transaction, as well as develop long-term trends capable of communication to the balanced reciprocity sector (cf. Pospisil, 1963, pp. 310-311).

8. In speaking of short-term sluggishness in the face of supply and demand unbalance, it is necessary to bear in mind that the reference is'to customary rates, especially if the economy includes a sector of haggling. Bargaining proceeds from various degrees of desperation and advantage, personal positions that do not individually represent the aggregate supply and demand and result in marked differences from transaction to transaction in rates of exchange. In Marshall's terms, bargainers can come to an equilibrium, but only fortituitously to the equilibirum (1961, pp. 791-793). Unless and until other people get into the bargaining, both on the demand side and the supply side, such paired haggling does not constitute a "market principle" nor influence price in the way envisioned by the competitive model. Certain ethnographic suggestions that prices in one or another primitive society are even more responsive to supply/demand than in our markets, insofar as they derive from the haggling sector, ought to be treated with suspicion. In any event, these kinds of fluctuations are not involved in the present discussion of short-term stability.

The case is simpler in the Australian New Guinea Highlands, where the bulk of trade is carried at standardized rates and between special partners. Here currency values have dropped substantially since Europeans put large quantities of shell money into circulation (Gitlow, 1947, p. 72; Meggitt, 1957-58, p. 189; Salisbury, 1962, pp. 116-117). The same process has been observed outside Melanesia: the variations in exchange value of horses in the intertribal trade of the American Plains, due to changes in supply conditions. (Ewers, 1955, pp. 217f).

No doubt examples of such sensitivity to supply and demand could be multiplied. Yet more examples would only make matters more unintelligible—by any prevailing theory of exchange value. This theoretical embarrassment is noteworthy and critical, and although I may not resolve it I would count the essay a success to have raised it. Nothing really is explained by remarking that exchange value in primitive trade corresponds to supply/demand. For the competitive mechanisms by which supply and demand are understood to determine price in the market place do not exist in primitive trade. It becomes far more mysterious that exchange ratios should respond to supply and demand than that they remain unaffected.

Date: 2014-12-21; view: 1748

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Notes on Reciprocity and Wealth | | | The Social Organization of Primitive and Market Trade |