CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

HISTORICAL NOTE

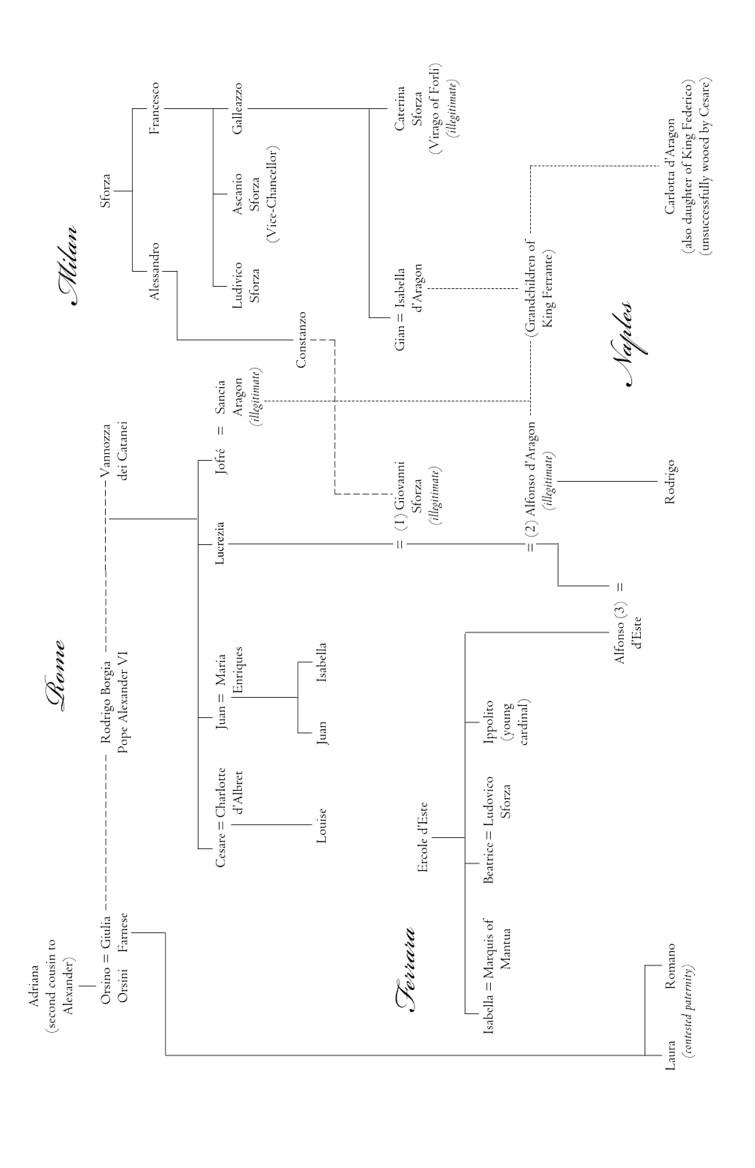

By the late fifteenth century, the map of Europe would show areas broadly recognisable to a modern eye. France, England, Scotland, Spain and Portugal were on their way to becoming geographical and political entities, run by inherited monarchies. In contrast, Italy was still a set of city-states, making the country vulnerable to invasion from outside. With the exception of the republic of Venice, most of these states were in the hands of family dynasties: in Milan the House of Sforza, in Florence the Medici, in Ferrara the Este and in Naples and the south the Spanish House of Aragon.

In the middle of all of this sat Rome, a bearpit of various established families jockeying for position, but also, more importantly, the seat of the papacy. While the Pope’s earthly territories were modest – and often leased out to papal vicars – his influence was immense. As head of the Church, the man himself, usually Italian, controlled a vast web of patronage throughout Europe; and as God’s representative on earth, he could and did wield spiritual power for strategic and political ends. With Catholicism reigning supreme and corruption in the Church endemic, it was not uncommon to find popes amassing wealth for themselves and favouring the careers and well-being of those in their family. In some cases, even their own illegitimate children.

Such was the situation in the summer of 1492, when the death of Innocent VIII left the papal throne in Rome empty, ready for its new incumbent.

PART I

We Have a Pope

He is the age when Aristotle says men are wisest: robust in body, vigorous in mind, perfectly equipped for his new position.SIGISMONDO DE CONTI, PAPAL SECRETARY, 1492 CHAPTER 1

August 11 , 1492

Dawn is a pale bruise rising in the night sky when, from inside the palace, a window is flung open and a face appears, its features distorted by the firelight thrown up from the torches beneath. In the piazza below, the soldiers garrisoned to keep the peace have fallen asleep. But they wake fast enough as the voice rings out:

‘WE HAVE A POPE!’

Inside, the air is sour with the sweat of old flesh. Rome in August is a city of swelter and death. For five days, twenty-three men have been incarcerated within a great Vatican chapel that feels more like a barracks. Each is a figure of status and wealth, accustomed to eating off silver plate with a dozen servants to answer his every call. Yet here there are no scribes to write letters and no cooks to prepare banquets. Here, with only a single manservant to dress them, these men eat frugal meals posted through a wooden hatch that snaps shut when the last one is delivered. Daylight slides in from small windows high up in the structure, while at night a host of candles flicker under the barrel-vaulted ceiling of a painted sky and stars, as vast, it seems, as the firmament. They live constantly in each other’s company, allowed out only for the formal business of voting or to relieve themselves, and even in the latrines the work continues: negotiation and persuasion over the trickle of ageing men’s urine. Finally, when they are too tired to talk, or need to ask guidance from God, they are free to retire to their cells: a set of makeshift compartments constructed around the edges of the chapel and comprised of a chair, a table and a raised pallet for sleeping; the austerity a reminder, no doubt, of the tribulations of aspiring saints.

Except these days saints are in short supply, particularly inside the Roman conclave of cardinals.

The doors had been bolted on the morning of August 6. Ten days earlier, after years of chronic infirmity, Pope Innocent VIII had finally given in to the exhaustion of trying to stay alive. Inside their rooms in the Vatican palace, his son and daughter had waited patiently to be called to his bedside, but his final moments had been reserved for spatting cardinals and doctors. His body was still warm when the stories started wafting like sewer smells through the streets. The wolf pack of ambassadors and diplomats took in great lungfuls, then dispatched their own versions of events in the saddlebags of fast horses across the land: stories of how His Holiness’s corpse lay shrivelled, despite an empty flagon of blood drained from the veins of Roman street boys on the orders of a Jewish doctor, who had vowed it would save his life; how those same bloodless boys were already feeding the fishes in the Tiber as the doctor fled the city. Meanwhile, across the papal bedclothes, the Pope’s favourite, the choleric Cardinal della Rovere, was so busy trading insults with the Vice-Chancellor, Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, that neither of them actually noticed that His Holiness had stopped breathing. Possibly Innocent had died to get away from the noise, for they had been rowing for years.

Of course, in such a web of gossip each man must choose what he wants to believe; and different rulers enjoy their news, like their meat, more or less well spiced. While few will question the cat claws of the cardinals, others might wonder about the blood, since it is well known around town that His Holiness’s only sustenance for weeks had been milk from a wet-nurse installed in an antechamber and paid by the cup. Ah, what a way to go to heaven: drunk on the taste of mother’s milk.

As for the conclave that follows, well, the only safe prediction is that prediction is impossible: that and the fact that God’s next vicar on earth will be decided as much by bribery and influence as by any saintly qualifications for the job.

At the end of the third day, as the exhausted cardinals retire to their cells, Rodrigo Borgia, Papal Vice-Chancellor and Spanish Cardinal of Valencia, is sitting appreciating the view. Above the richly painted drapery on the walls of the chapel (new cardinals have been known to try and draw the curtains) is a scene from the life of Moses: Jethro’s daughters young and fresh, the swirl of their hair and the colour of their robes singing out even in candlelight. The Sistine Chapel boasts sixteen such frescos – scenes of Christ and Moses – and those with enough influence may choose their cell by its place in the cycle. Lest anyone should mistake his ambition, Cardinal della Rovere is currently sitting under the image of Christ giving St Peter the keys of the Church, while his main rival, Ascanio Sforza, has had to settle for Moses clutching the tablets of stone (though with a brother who runs the bully state of Milan, some would say that the Sforza cardinal has more on his side than just the Commandments).

Publicly, Rodrigo Borgia has always been more modest in his aspirations. He has held the post of vice-chancellor through the reign of five different pontiffs – a diplomatic feat in itself – and along with a string of benefices it has turned him into one of the richest and most influential churchmen in Rome. But there is one thing he has not been able to turn to his advantage: his Spanish blood. And so the papal throne itself has eluded him. Until now, perhaps; because after two public scrutinies there is deadlock between the main contenders, which makes his own modest handful of votes a good deal more potent.

He murmurs a short prayer to the virgin mother, reaches for his cardinal’s hat, and pads his way down the marble corridor between the makeshift cells until he finds the one he is looking for.

Inside, somewhat drained by the temperature and the politicking, sits a young man with a small Bacchus stomach and a pasty face. At seventeen, Giovanni de’ Medici is the youngest cardinal ever to be appointed to the Sacred College, and he has yet to decide where to put his loyalty.

‘Vice-Chancellor!’ The youth leaps up. The truth is one can only wrestle with Church matters for so long and his mind has wandered to the creamy breasts of a girl who shared his bed in Pisa when he was studying there. There had been something about her – her laugh, the smell of her skin? – so that when he feels in need of solace it is her body that he rubs himself against in his mind. ‘Forgive me, I did not hear you.’

‘On the contrary – it is I who should be forgiven. I disturb you at prayer!’

‘No… Not exactly.’ He offers him the one chair, but the Borgia cardinal brushes it away with a wave of the hand, settling his broad rump on the pallet bed instead.

‘This will do well enough for me,’ he says jovially, slapping his fist on the mattress.

The young Medici stares at him. While everyone else is wilting under the relentless heat, it is remarkable how this big man remains so sprightly. The candlelight picks out a broad forehead under a thatch of tonsured white hair, a large hooked nose and full lips over a thick neck. You would not, could not, call Rodrigo Borgia handsome; he is grown too old and stout for that. Yet once you have looked at him you do not easily look away, for there is an energy in those sharp dark eyes much younger than his years.

‘After living through the election of four popes I have grown almost fond of the – what shall we call it? – “challenges” of conclave life.’ The voice, like the body, is impressive, deep and full, the remnants of a Spanish accent in the guttural trim on certain words. ‘But I still remember my first time. I was not much older than you. It was August then too – alas, such a bad month for the health of our holy fathers. Our prison was not so splendid then, of course. The mosquitoes ate us alive and the bed made my bones ache. Still, I survived.’ He laughs, a big sound, with no sense of self-consciousness or artifice. ‘Though of course I did not have such a remarkable father to guide me. Lorenzo de’ Medici would be proud to see you take your place in conclave, Giovanni. I am sincerely sorry for his death. It was a loss not just for Florence but for all of Italy.’

The young man bows his head. Beware, my son. These days Rome is now a den of iniquity, the very focus of all that is evil. Under his robes he holds a letter from his father: advice on entering the snakepit of Church politics from a man who had the talent to skate on thin ice and make it look as if he was dancing. Few men are to be trusted. Keep your own counsel until you are established. Since his death only a few months before, the young cardinal has learned its content by heart, though he sorely wishes now that the words were less general and more particular.

‘So tell me, Giovanni…’ Rodrigo Borgia drops his voice in an exaggerated manner, as if to anticipate the secrets they are about to share, ‘how are you holding up through this, this labyrinthine process?’

‘I am praying to God to find the right man to lead us.’

‘Well said! I am sure your father railed against the venality of the Church and warned against false friends who would take you with them into corruption.’

This current college of cardinals is poor in men of worth and you would do well to be guarded and reserved with them. The young man lifts an involuntary hand to his chest, to check the letter is concealed. Beware of seducers and bad counsellors, evil men who will drag you down, counting upon your youth to make you easy prey. Surely not even the Vice-Chancellor’s hawk eyes are able to read secrets through two layers of cloth?

Outside, a shout pierces the air, followed by the shot of an arquebus: new weapons for new times. The young man darts his head up towards the high, darkened window.

‘Don’t fret. It’s only common mayhem.’

‘Oh… no, I am not worried.’

The stories are well known: how in the interregnum between popes Rome becomes instantly ungovernable, old scores settled by knife-thrusts in dark alleys, new ones hatched under cover of an exuberant general thuggery that careers between theft, brawling and murder. But the worst is reserved for the men who have been too favoured, for they have the most to lose.

‘You should have been here when the last della Rovere pope, Sixtus IV, died – though not even Lorenzo de’ Medici could have made his son a cardinal at the age of ten, eh?’ Rodrigo laughs. ‘His nephew was so hated that the mob stripped his house faster than a plague of locusts. By the time conclave ended only the walls and the railings remained.’ He shakes his head, unable to conceal his delight at the memory. ‘Still, you must feel at home sitting here under the work of your father’s protégés.’ He lifts his eyes to the fresco on the back wall of the cell: a group of willowy figures so graceful that they seem to be still moving under the painter’s brush. ‘This is by that Botticelli fellow, yes?’

‘Sandro Botticelli, yes.’ The style is as familiar to the young Florentine as the Lord’s Prayer.

‘Such a talented man! It is wonderful how much… how much flesh he gets into the spirit. I have always thought that Pope Sixtus was exceedingly lucky to get him, considering that three years before he had launched a conspiracy to kill his patron, your own father, and wipe out the whole Medici family. Fortunately you are too young to remember the outrage.’

But not so young that he could ever be allowed to forget. The only thing bloodier than the attack had been the retribution.

‘Luckily, he survived and prospered. Despite the della Rovere family,’ Rodrigo adds, smiling.

‘My father spoke highly of your keen mind, Vice-Chancellor. I know I shall learn a lot from you.’

‘Ah! You already have his wit and diplomacy, I see.’ And his smile dissolves into laughter. The candle on the table flutters in the wind of his breath and his generous features dance in the light. The younger man feels a bead of sweat moving down from his hair and wipes it away with his hand. His fingers come away grimy. In contrast, the Borgia cardinal remains splendidly unaffected by the heat.

‘Well, you must forgive me if I show a certain fatherly affection. I too have a son of your age who needs counsel as he climbs the ladder of the Church. Ah – but of course, you know this. The two of you studied together in Pisa. Cesare spoke often of you as a good friend. And an outstanding student of rhetoric and law.’

‘As I would speak of him.’

In public. Not in private. No. In private, the cocky young Borgia was too closeted by his Spanish entourage to be a friend to anyone. Which is just as well, since whatever money he put on his back (and there was always a sack of it; when he came to dine you could barely see the cloth for the jewels sewn on to it) a Borgia bastard could never be the social equal of a legitimate Medici. He was clever though, mentally so fast on his feet that in public disputation he could cut to the quick, pulling arguments like multi-coloured threads from his brain until black seemed to turn into white and wrong became just another shade of grey. Even the praise of his tutors seemed to bore him: he lived more in the taverns than the study halls. But then he was hardly alone in that fault.

The young Medici is glad of the shadows around them. He would not like such thoughts to be exposed to daylight. If the emblem on the Borgia crest is that of the bull, everyone knows it is the cunning of the fox that runs in the family.

‘Well, I admire your dedication and pursuit of goodness, cardinal.’ Rodrigo Borgia leans over and puts his hand gently on his knee. ‘It will loom large in God’s grace.’ He pauses. ‘But not, I fear, in the annals of men. The sad truth is that the times in which we live are deeply corrupt, and without a pope who can withstand the appetites of the wolves prowling around him, neither he nor Italy will survive.’

While the back of his hand lies thick as a slab of meat, his fingers are surprisingly elegant, tapered and well manicured, and for a second the younger man finds himself thinking of the woman who graces the Vice-Chancellor’s bed these days. A flesh-and-blood Venus she is said to be: milk-skinned, golden-haired and young enough to be his granddaughter. The gossip is tinged with disgust that such sweetness should couple with such decay, but there is envy there too; how easily beauty snaps on to the magnet of power, whatever a man’s looks.

‘Vice-Chancellor.’ He takes a breath. ‘If you are here to canvass my vote…’

‘Me? No, no, no. I am but a lamb in this powerful flock. Like you, I have no other wish but to serve God and our holy mother the Church.’ And now the older man’s eyes sparkle. They say that while Giuliano della Rovere has a temper fit to roast flesh, it is the Borgia smile that is more to be feared. ‘No. If I put myself forward at all it is only because, having seen such things before, I fear that a deadlock could push us into hands less capable even than my own.’

Giovanni stares at him, wondering at the power of a man who can lie so bare-facedly and still give the impression that his heart is in his voice. Is this then his secret? In these last few days he has had occasion to watch him at work; to notice how tirelessly he weaves in and out of the knots of other men, how he is first to help the elder ones to their cells, or to find the need to relieve himself when negotiations stick and new incentives are called for. A few times the younger man has walked into the latrines and found the conversation fall silent at his entrance. And almost always the Vice-Chancellor will be there himself, nodding and beaming over his large stomach with his tool held loosely in his hand, as if it was the most natural pose on earth for God’s cardinals to adopt in each other’s presence.

Inside the cell, the air feels as thick as soup. ‘Sweet Mary and the saints. If we are not careful we will boil alive as slowly as Saint Cyrinus.’ Rodrigo fans his face theatrically and digs inside his robes, holding out a glass vial with an intricate silver top. ‘Can I offer you relief?’

‘No, no thank you.’

He digs a finger inside and anoints himself liberally. As the young man catches the tang of jasmine, he remembers how he has detected remnants of it – and a few other scents – around the public spaces over the last few days. Does each camp, like a pack of dogs, identify itself by its smell?

The cardinal is making a business of putting the bottle back in his robes while he stands up to take his leave. Then, suddenly, he seems to change his mind.

‘Giovanni, it seems to me you are too much your father’s son not to recognise what is happening here. So I shall tell you something I have not made public.’ And he bends his large frame to get closer to the young man’s face. ‘Don’t be alarmed. Take it as a tribute to your family that I share it: a lesson as to how influence moves when the air grows as thick as stinking cheese. Della Rovere cannot win this election, however it may look now.’

‘How do you know that?’ the young man says quickly, the surprise – and perhaps the flattery – overcoming the reticence he had vowed to hold.

‘I know it because, as well as being able to count, I have looked inside men’s hearts here.’ He smiles, but there is less mirth in him now. ‘In the next public scrutiny the della Rovere camp will pick up more votes, which will put him ahead of Sforza, though not enough to secure victory outright. When that happens Ascanio Sforza, who would not make a bad pope, though he would favour Milan too much for Florence – and you – to ever stomach him, will start to panic. And he will be right to do so. Because a papacy controlled by della Rovere will be one that favours whoever pays it the most. And the money that he is using to buy his way there now is not even his own. You know where it comes from? France! Imagine. An Italian cardinal bought by France. You have heard the rumour, I am sure. Gross slander, you think, perhaps? Except that in this city slander is usually less foul than the truth.’ He gives an exaggerated sigh. ‘It would be disastrous of course: a foreign power sitting in the papal chamber. So, to sink his rival, Ascanio Sforza will turn to me.’

He stops as if to let the words sink in.

‘Because at that point I will be the only one who can stop the water from rushing downhill in that direction.’

‘Turn to you? But—’ I say it again, my son: until you become accustomed, you would do well to make use of your ears rather than your tongue. ‘But I thought…’ He trails off.

‘You thought what? That a Borrjja pope would be a foreigner too,’ he says, resurrecting the hawking guttural of his name. ‘A man who would advance only his family and be more loyal to Spain than to Italy.’ For a moment there is a flash of undisguised anger in his eyes. ‘Tell me – would a Medici pope care less about the Holy Mother Church because he loves his family and comes from Florence?’

‘Cardinal Borgia, it was not my intention—’

‘To offend me? No! And neither did you. Powerful families must speak openly to each other. I would expect no less.’

He smiles, only too aware that the comparison between the two could be read as offence the other way.

‘Yes, I am a Borgia. When I embrace my children we speak in our native tongue. But I defy anyone to say I am less Italian than those who would now put their noses into the French coffers. If the papal crown is up for sale – and as God is my witness I did not start such a process – then at least let us keep the sale inside this room.’ He sighs again and claps him on the shoulder. ‘Ah! I fear I have said too much. See! You have pulled the truth from me. Your father’s blood runs deep in your veins. Such a politician he was! Always with one finger held up wet to the wind so that when he felt it changing he could move the sails to keep his ship of state on course.’

The young Medici does not answer. He is too impressed by the show. The politics of charm. Having grown up with a father who could turn vinegar to honey when it suited him, he knows better than most how it works; but this mix of geniality, cunning and theatrics is new even to him.

‘You are tired. Get some rest. Whatever happens it will not be settled until tomorrow at least. You know, I think my Cesare would look almost as fine as you inside scarlet robes.’ And the last smile is the brightest of all, possibly because there is no dissembling. ‘I can see you both standing together, tall and strong as cypress trees. Imagine what a fire such youth and energy would light under this deadwood of old men.’ And he lets out a gale of laughter. ‘Ah, the foolish pride of men who love their sons better than themselves.’

After he has gone the young man sits examining all that he has heard, but while he should be considering the next public scrutiny, he cannot get the image of Cesare Borgia in scarlet out of his mind. He sees him inside a tight knot of men, striding through the streets of Pisa as if every closed door will open to him before he has to knock, and even then he might not choose to go in. God knows the government of the Church is full of men who have only a passing acquaintance with humility, but however contemptuous or lazy (and he is too much his father’s son not to know his own failings), in public at least they make an effort to do what is expected of them. But never Cesare Borgia.

Well, whatever the Borgia arrogance, his father’s ambitions will fail him. He might be laden with Church benefices, but he will rise so far and no further. Canon law, which they have wasted years of their lives studying, is marvellously clear on this: though there are riches to be had for those born on the other side of the blanket, no bastard – even a papal one – can enter the Sacred College of cardinals.

Outside, people are gathering in readiness for supper. He hears Rodrigo Borgia’s laughter ringing out from somewhere in the main body of the room where the more public canvassing takes place. If the della Rovere camp is to gain votes before losing, then someone must be canvassing for him now, in order to make victory seem secure.

From under his robes he pulls out his father’s letter, the paper limp with a sweat that comes from more than the heat of the room. For the first time since he has set foot in the conclave, when he gets to his knees the prayers come from the heart.

CHAPTER 2

Next morning, the third scrutiny of the conclave takes place in the formal antechamber off the great chapel.

The count shows the della Rovere faction pulling ahead by a small but appreciable margin. Della Rovere sits stony-faced, too good a politician to give anything away, but Ascanio Sforza, who wears both his pleasure and his pain on his sleeve, registers his alarm immediately. He glances nervously in the direction of the Vice-Chancellor, but the Borgia cardinal keeps his eyes down as if in prayer.

Outside, the camps disperse in their different directions. Borgia takes his leave to visit the latrine. Sforza watches him go, moving nervously from one foot to another, as if his own bladder is about to burst. The doors have barely closed when he follows. When he comes out a few moments later he is ashen. His brother may rule over a swathe of northern Italy, but it is a different kind of muscle needed here. He disappears into the throng. After a while a few of his most powerful supporters also feel the call of nature. Finally, Borgia himself emerges. For once he is not smiling. It is the countenance of a man who seems resigned to the process of defeat. Except of course such a pose would be exactly what was called for if the losers were turning the tables on the winners before they knew it was happening.

Despite the locked doors, by the time darkness falls the news has slipped like smoke out of the Vatican palace and is gossip at the city’s richest dinner tables, so that all the great families, the Colonna, the Orsini and the Gaetani (each with their own interested cardinals in the fight), go to bed that night with the name of the della Rovere family rolling round their mouths, the winners dreaming of the spoils in their sleep.

Meanwhile, halfway between the Ponte Sant’ Angelo and the Campo de’ Fiori, darkness provides cover for another kind of business. The Borgia palace is known throughout Rome as a triumphant marriage of taste and money. It is not only the house of an immensely wealthy cardinal, but also the office of the vice-chancellorship, raising revenues for the papacy and a profitable accounting business in itself. Before the final scrutiny takes place, those who are paid to watch for such things claim they spot the stable doors at the side of the palace opening to let out a pack of animals. First comes a fast horse – a Turkish pure-bred, no less – carrying a cloaked rider. Following on are six mules. The horse has already reached the northern city gate while the mules still plod their way up one of Rome’s seven hills. But then silver makes a heavy load, even for beasts of burden. Eight bags of it, they say, each one packed long before, for so much money can never have been counted in one night. Its destination? The palace of Cardinal Ascanio Sforza. If defeat is bitter then there are ways to sweeten the taste it leaves behind.

Inside the conclave, the gold-painted stars in the Sistine Chapel ceiling look down on a night of high activity. Old and young, venal and saintly are all kept awake by the chatter of men. So much horse-trading is taking place that it is a wonder men do not come with abacuses under their robes, so they can work out the profit margins on the offered benefices faster. Once the tide starts to turn the trickle soon becomes a flood. Plates of food are left untouched. The wine is drained and there are calls for more to be passed through the hatch. Johannes Burchard, the German Master of Papal Ceremonies and a man of exquisite precision, notes each request and the time of it down in his book. What he himself thinks remains a secret between him and his diary.

It is the stillest, deadest time of night when the cardinals take their place in formal circle in their great, carved wooden chairs under canopies, each one embroidered with the crests of their individual benefices. The air is a mix of stale body odour, dust and heavy perfumes. Most of them are ragged with tiredness, but there is no mistaking the underlying excitement in the room. To be part of history is a heady business, especially if you can make a profit from it yourself.

The vote is taken in silence.

Now as the result is announced the room erupts into a loud ‘AAAAH’ in which it is not easy to distinguish fury from triumph. All eyes turn towards the Borgia cardinal.

Tradition calls for only a single word. ‘Volo.’ ‘I want.’ But instead this big man, fine-schooled in politics and subterfuge, leaps up from his seat, brandishing both his fists high in the air, a prize fighter with his greatest opponent at his feet.

‘Yes! Yes. I am the Pope…’ And he lets out a great guffaw of childish delight.

‘I AM THE POPE.’

‘HABEMUS PAPAM!’ ‘WE HAVE A POPE!’

At the palace window the figure pauses, gulping in the fresh night air. Now another figure joins him, arms outstretched with tightly closed fists, like a street magician about to deliver a trick. The hands unclench and a storm of paper scraps is released. They flutter down in the breaking light, a few catching on the dying embers of the torches and flaring up like drunken fireflies. Such a piece of theatre has never been seen in the history of a conclave and the people below jump and fight each other to catch them before they land. Those who can read screw up their eyes to decipher the words scribbled there. Others hear it from the voice.

‘… Rodrigo Borgia, Cardinal of Valencia, is elected Pope Alexander VI.’

‘Bor-g-i-a! Bor-g-i-a!’

The crowd goes wild at the name, the square fuller by the second as the news brings people running from the warren of steamy streets on either side of the Ponte Sant’ Angelo, the old stone bridge that crosses the Tiber. After such a wait, they would probably cheer the devil himself. Yet this is more than fickle love. The established families of Rome may moan about tainted foreign blood and a language that sounds like hacking up phlegm, but those with nothing to lose warm to a man who opens his purse and palace at the drop of a feast day. And Rodrigo Borgia has been spending his way into Roman hearts for a long time.

‘BOR-G-I-A!’

Unlike many rich men, he always makes it clear how much he enjoys the giving. No discarded basement hangings or half-hearted generosity from this vice-chancellor. Oh no: when a foreign dignitary tours the city or the Church parades its latest relics, it’s always the streets outside the Borgia palace that are strewn with the freshest flowers, always his windows that unfurl the biggest, brightest tapestries, his fountain that turns water into wine faster and longer, his entertainments that tickle the most jaded palates with firework displays that light the night sky into the dawn.

‘BOR-G-I-A!’

It was barely six months ago when Rome celebrated the fall of Moorish Granada to the armies of Christendom. A triumph for his native Spain as well as for the Church, and he had opened his palace and turned his courtyard into a bullring, with such a frenzy of the sport that one of the bulls, goaded into madness, had run amok in the crowd, spearing half a dozen spectators on its horns. In swift retaliation it had been skewered by the young Cesare, his church garments discarded in favour of full matador finery. How he brought the raging bull to its knees and then severed its throat with a single knife-thrust was all anyone could talk about for days. That and the money paid out to the families of the two men who later died of their wounds. The purse of a wealthy old man and the athletic prowess of his strutting son. Generosity and virility entwined. What better advertisement could there be for the reign of a new pope?

The runners are already spreading into the city. At the Ponte Sant’ Angelo moored boatmen slip their oars into the water and cut a rapid line towards the island and Ponte Sisto, broadcasting the news as they go. Others cross the river then span east into the thoroughfare of the bankers, the ground-floor trading houses still boarded up against random violence, or south into the busiest part of the city, where rich and poor live separated by alleyways or open sewers, all huddled inside the great protective curve of the Tiber.

‘ALLESSANDEER.’

In a second-storey bedroom in a palace on Monte Giordano, a young woman wakes to the sound of men, rat-arsed on gossip and booze, careering their way down the street. She flips over in the bed to where her companion lies sleeping, one shapely arm flung across the sheet, thick eyelashes laid on downy pale cheeks with lips like peach flesh, open and pouting.

‘Giulia…?’

‘Hummm?’

They are not usual sleeping companions, these two young beauties, but with the nerves of the house all a-jangle, they have been allowed to keep each other company, listening for the shouts of the mob and teasing each other with stories of chivalry and violence. Two nights before, a man had been running through the streets howling, begging for his life, a gang at his heels. He had thrown himself against the great doors, hammering to be let in, but the bolts had remained in place as his screams turned to gargles of blood and the girls had had to put their heads under the pillows to shut out the death rattle. Come the dawn, Lucrezia had watched as a band of friars in black robes picked up the body from the gutter and placed it on a cart to be taken, along with the rest of the morning harvest of death, to the city morgue. In the convent she used to dream sometimes about the wonders of such work: seeing herself swathed in white, a young St Clare aglow with poverty and humility, eyes to the ground, as the howling mob parted to greet her saintliness.

‘G… IA… HABEMUS BORGIA.’

‘Giulia! Wake up. Can you hear them?’

She has never liked sleeping alone. Even as a small child, when her mother or the servant had left her and the darkness started to curdle her insides, she would steel herself to brave the black soup of the room as far as her brother’s bed, creeping in beside him. And he, who when awake would rather fight than talk, would put his arms around her and stroke her hair until their warmness mingled and she fell asleep. In the convent she had asked to share the dormitory rather than the privilege of a single cell that was owed to her. By the time she came out, Cesare was long gone and her aunt impatient with what she called such nonsense.

‘And what will you do when you are married and sent off to Spain? You cannot have your brother with you then.’

No, but the handsome husband they had promised her would surely guard her instead, and when he was out at war or business she would keep a group of ladies around her, so they might all sleep together.

‘AALESSANDER. VALEEEENCIA. BOOORGIA… YEAAAH.’

‘Wake up, Giulia!’ She is upright in bed now, pulling off the anointed night gloves that she must wear to keep her hands white. ‘Can you hear what they are shouting? Listen.’

‘BORGIA, ALEXANDER.’

‘Aaaah.’ And now they are both shouting and scrambling, clambering over each other to get from the bed to the window, the nets slipping off their heads and fat ropes of hair escaping and tumbling down their backs. They can barely breathe with excitement. Lucrezia is pushing at the shutter locks, though it is strictly forbidden to open them. The great bolts jump free and the wooden boards snap apart, flooding the room with the light of a white dawn. They dart their heads quickly to look down on to the street, then pull back as one of the men below spots them and starts yelling. They slam the shutters again, convulsed with laughter and nerves.

‘Lucrezia! Giulia!’ The voice of Lucrezia’s aunt has the reach of a hunting trumpet.

She is standing at the bottom of the great curved stone staircase, hands on stout hips, plump face flushed and small dark eyes shining under black eyebrows which grow thicker and closer together the more she plucks them: aunt, widow, mother, mother-in-law and cousin, Adriana da Mila, Spanish by birth, Roman by marriage but first, last and always a Borgia.

‘Don’t open the shutters. You will cause a riot.’

Later, she will bore the world and its wife with the story of how she herself learned the news. How she had been woken in the dead of night, ‘so black I could not see my hand in front of my face’, by what felt like the stabbing of a dozen needles in her mouth. Such a vicious tooth pain that it was all she could do to pull herself out of bed and make her way to the great stone staircase in search of the bottle of clove wine. She had been halfway down when her taper had gone out. ‘As suddenly as if someone had put a snuffer cap over it.’

It was then that it had happened: something or someone had passed by her in a great wind. And though she should have been in terror for her life, for the city was full of burglars and brigands, instead she had felt warmth and wonder filling her whole being, and she had known, ‘known – as certainly as if they had stopped and whispered it in my ear’, that her cousin, Vice-Chancellor and Cardinal of Valencia, was chosen as God’s vicar on earth. The pain had disappeared as fast as it had come and she had fallen on her knees on the stone steps then and there to give thanks to God.

As the city stirred she had dispatched a hasty letter and woken the servants. Theirs would soon be one of the most important houses in Rome and they must be ready for a deluge of visitors and feasts. She had been about to rouse her charges when she heard the girls’ voices and the crack of the shutter frame.

‘If you are so awake, you had better come down here.’

Her command is met by a tumble of laughter and voices, as the two young women throw themselves out of their room, across the landing and on to the stairs.

A stranger seeing them now might well think they are sisters, for though the elder is clearly the star – her adult beauty too arresting to brook comparison, while the younger is still closed in the bud – there is a camaraderie and intimacy between them which speaks more of family than friendship. ‘Borgia! Valencia! That’s what they’re calling. Is it true, aunt?’

Lucrezia takes the last flight so fast that she can barely stop herself from colliding into her aunt at the bottom. As a child it was always her way to greet her father thus, launching herself into his arms from the steps, while he would pretend to stagger as he caught her. ‘It is him, yes? He has won?’

‘Yes, by the grace of God, your father is elected Pope. Alexander VI. But that is no reason to parade round the house like a half-dressed courtesan with no manners. Where are your gloves? And what of your prayers? You should be on your knees thanking Our Lord Jesus Christ for the honour He brings upon the family.’

But all this only meets with more laughter, and Adriana, who even in stately middle age still has something of the child in her, is won over. She hugs this young woman fiercely to her, then holds her at arm’s length, pushing back the shock of chestnut hair, not so full nor so golden as Giulia’s, but wonder enough in a city of raven-haired beauty.

‘Oh, look at you. The daughter of a pope.’ And now there are tears in her laughter. Dear God, she thinks, how fast it has gone. Surely it cannot be so many years? The child had been not yet six when she had arrived to live with her. What bloody murder she had screamed at being taken from her mother. ‘Oh, enough now, Lucrezia.’ She had tried her best to soothe her. ‘You will see her still. But this is to be your home now. It is a noble palace and you will grow up here as a member of the great family to which you belong.’

But the soothing had only made her sob louder. The only comfort she would take was from Cesare. How she worshipped her brother. For weeks she would not let him out of her sight, following him around, calling his name like a bleating lamb until he would have to stop to pick her up and carry her with him, though he was barely big enough himself to stand the weight. And when Juan mocked her for her weakness, he would punch and wrestle him until the younger one ran screaming to whoever would listen. And then the baby Jofré would join in, until the house was like a mad place and she had no idea how to calm them.

‘Ah, we Borgias always cry as hard as we laugh.’ It did not help that Rodrigo always indulged them so, allowing everyone to yell and climb all over him the minute he walked in. ‘It is our nature to feel each slight and compliment more deeply than these insipid Romans,’ he would say, besotted by whatever incident or story of misbehaviour had just been recounted. ‘They will settle soon enough. Meanwhile look at her, Adriana. Feast your eyes on that perfect nose, those cheeks plump as orchard plums. Vannozza’s beauty is there already. Her mother’s looks and her father’s temperament. What a woman she will become.’

And how nearly she is there, Adriana thinks as she stares at Lucrezia now. Fourteen next birthday and already her name is on a betrothal contract to a Spanish nobleman with estates in Valencia. Her eyes will shine as brightly as any of the gold in her dowry. But then they are all handsome, these bastard children of Rodrigo Borgia. How merciful of God to so readily forgive the carnal appetites of a servant he has singled out for greatness. Had she been a more envious woman, Adriana might feel some resentment; she who despite Borgia blood and an Orsini marriage had only managed to squeeze out one scrawny, cock-eyed boy before her miserable, miserly husband died in apoplexy.

Life had been infinitely richer since his death. No widow’s cell in a convent for her. Instead, her beloved cardinal cousin Rodrigo had made her guardian of his four children, and the status had brought her a pleasure as deep as the responsibility she felt on their behalf. Family. The greatest loyalty after God in the world. For these eight years she has given it everything: no lengths she has not gone to to elevate their name, nothing she would not do for her handsome, manly cousin. Nothing, indeed, that she has not done already.

‘And good morning and congratulations to you, daughter-in-law.’

She turns now to the oh-so-lovely creature who stands nest-ripe and willowy on the top step, and for a second her beauty takes her breath away. It had been the same three years before, when Giulia’s marriage to her son had been first suggested by the cardinal, a man who could make even an act of procurement – for that was what it was – an elegant proposal.

‘Giulia Farnese is her name: a magnificent girl, sweet, unaffected. Not a fabulously rich family, but you may trust me that that will change soon enough. After their marriage, young Orsino will want for nothing. Not now, nor ever again. He will be a rich man with an estate in the country to rival any of his father’s family, and the freedom to do with it as he wants. As his mother – and in many ways the mother of all our family – he will, I know, listen to you. What do you say, Adriana?’

And he had sat back smiling, hands clasped over spreading stomach. What she had said had been easy. What she had felt, she had buried too deep to allow access. As for the feelings of the girl herself, well, they had not been discussed. Not then and never since that day. At the time of the wedding the girl had not been much older than Lucrezia is now, but with a more lovely – and perhaps more knowing – head on her shoulders. In a city of men sworn to celibacy, beauty such as hers is its own power broker, and with the promise of the papacy there is already talk of a cardinal’s hat for one of her brothers. Family. The greatest loyalty after God.

‘You slept well, Giulia?’

‘Until the noise, well enough.’ The young woman’s voice, sweet though it is, is nowhere near as melodious as her body. She pulls back the long strands of hair that have slipped around her face, while the rest falls down her back, a sheet of gold reaching almost to her knees. That hair, along with the scandalous smoke of her marriage, is the stuff of the latest Roman gossip: Mary Magdalene and Venus fusing into the same woman in a cardinal’s boudoir. It is said that the Vice-Chancellor moves his intercessional painting of the Virgin into the hall on those nights, lest the blessed Mary should be offended by what she might see. ‘When should I be ready? When will I be called for?’

‘Oh, I am sure His Holiness will be busy with great business for some days. We must not expect a visit soon. Use the time to be at your toilet, sweeten your breath and choose carefully from your wardrobe. I do not need to tell you, Giulia, the wondrous favour that is now bestowed upon us all. And perhaps most upon you. To be the mistress of a pope is to be in the eye of all the world.’

And a flush of colour rises in the girl’s cheeks, as if she is indeed a little overwhelmed by the honour. ‘I know that. I am prepared. But I… should…’ She hesitates. ‘I mean – what about Orsino?’

Rodrigo was right, as always. Sweetness, and a certain simplicity in her honesty. They were lucky. Beauty such as hers could easily breed malice or manipulation. Adriana gives the tight little smile with which they have all grown familiar. ‘You need not concern yourself with that. I have written to my son already and the letter is dispatched. With God’s grace he will receive it before the news becomes general knowledge.’

‘I… Even so, I should surely add some words of my own… He is my husband… I mean – things will be—’

‘Things will be as they will be. Your husband is as much a Borgia as he is an Orsini and he will be proud for the honour of his family. As you should be for yours. There will be wonders in this for everyone. This house will become an embassy for suitors in search of favours. We will have to ask Rodrigo for a full-time secretary to deal with the weight of petitions.’

Now Lucrezia intervenes, laughing, taking Giulia’s hands. ‘You are not to worry, Liana. Orsino will be happy for you, I am sure.’ She holds her gaze, until she coaxes a smile out of her. ‘And we shall visit him sometimes in the country to cheer him up. But mostly we shall hold court together in the great salon. Aunt Adriana will bring in the visitors and break the seal on the letters, yes? And then you and I will read them and assess each one for its worth. And those we think are worthy we will present their suits to Papà when he comes and he will congratulate us on our judgement, as his domestic ambassadors.’

And all three women are laughing, because the last few days their nerves have been pulled as tight as garrotting wire and the thing that they have most desired, even if also a little feared, has happened.

‘And we will not let Juan or Jofré into the room. For they will all have come to visit us, not brawling, spotty boys. Isn’t that so, aunt? Where are they? Do they know? They can’t still be asleep?’

Oh yes they can, thinks Adriana, for after all these years she knows her charges well. Jofré will be curled up with his thumb in his mouth like the ten-year-baby he still is, while Juan too will be in bed, though most likely it will not be his own. Whoever she is this time, she will probably try to charge him more when she learns who he is now become. Or offer it for free… a set of silken handcuffs. Rome. The city of the Holy Mother Church, renowned for being home to as many courtesans as clerics. There have been moments when Adriana has wondered if God is too busy keeping the Turks at bay to notice the exuberance of sins elsewhere. Still, they must all be more careful now. She must get Rodrigo… no, Alexander – His Holiness – what must they call him now when he visits? – she must get him to talk to the children, especially Juan. Make clear the responsibilities of this new status. Sweet Jesus, how the wheel of fortune spins. While they have been sleeping it has taken all of them and flung their lives around in ways that none of them can yet imagine.

CHAPTER 3

As the streets of Rome grow raucous with the news, inside the Vatican palace a transformation worthy of Ovid is taking place: a paunchy sixty-one-year-old is turning himself into one of the most powerful men in Christendom.

Rodrigo Borgia has said his private prayers: a jubilant outpouring of thanks to the Virgin Mary, Mother of God, his guiding light, his constant emissary and the only woman for whom his devotion is matched by unquestioning fidelity. His cardinal’s robes are now discarded on the floor and he stands naked, barrel chest and sagging abdomen over heavy legs, towelling the sweat off his flesh. In front of him, pressed and ready, sit three sets of papal raiments: three white undergarments, three flowing white silk robes and three caps, each set a different size to accommodate whatever shape of man should now find himself deserving of them. Over the course of his career Borgia has watched four men, at least one more dead than alive, emerge from this room transformed by the power of the robes. Each time he has had an image of himself in their place, while in between his body has grown as substantial as his desire.

He anoints himself with sweet musk oil: his forehead, under his arms and around his groin in an unconscious echo of the sign of the cross, and reaches for the largest undergarment.

From outside, he can hear the sound of the swelling crowd. He is humming to himself, lines from a motet by the Flemish musician whose compositions are becoming all the rage in the papal court. It has been inside him for days, this plaintive sweep of notes. Of course he will need to commission more music now, masses, special liturgies. A new era and a pope must make his mark on everything, from the allegiances of state to the melodies than run around men’s heads. So be it. The Walloon, what is his name? Des Prez? Yes, he will do for the music. Too eager to wait for the help that will come, he struggles with the main robe; a man doing battle inside a sea of silk, marvelling at the softness, which is as great as the weight. Soon he will be putting on the velvet and ermine. He had a coat with the same fur when he was young and vain enough to wear court robes alongside his clerical gowns. Ah, how grand he had thought himself then; stepping off the ship on to Italian soil, an iron-chested young Hercules, puffed up with Spanish confidence and Spanish manners, come to serve his cardinal uncle, soon to become Calixtus III, the first and – until now – the only Spaniard to ever accede to the holy throne.

It had not taken long to register the acrimony: the way accusations of nepotism went hand in hand with the sneers of the established Roman families. He had heard the first sniggers as soon as he walked into the room, noting how the more effete Italian clerics brought up their pomades to their noses and closed their eyes in a theatre of disgust, as if they might swoon at any moment. Though it would have given him more pleasure to punch their noses into the backs of their heads, instead he had done what was necessary, espousing the hygiene habits of his new country so effectively that for decades now he has been able to detect a newly arrived Spanish countryman from the smell that precedes him before he walks through the door. It makes up part of his first words of advice:

‘This obsession with bathing is something that the Romans share with the Arab infidel, but the truth is, brother, if you want to get on in this city…’

And then he flicks open a small pillbox and offers a perfumed lozenge to help sweeten the delivery of the language they must now talk, filled with blowsy open vowels. After so much practice his manners are more Italian than Spanish these days, yet there are those who still call him a Marrano, a Dago Jew behind his back. Except from now on, before they do so, they will have to make sure the doors and windows are bolted and that the company around them is either blood or bought.

And finally the papal cap. It fits awkwardly over the broad baldness of his tonsure. He squints into the shine of the brass vase: his white hair sitting like a ruffle of piped cream around a cake, the great eagle nose jutting out beneath. So, the biggest hat is too small. Well, it will do until there is another made. He stands back, lifting his right arm and bringing it down in a solemn gesture of blessing, the wonder of it all flooding through him, and it is all he can do not to cry out in triumph again.

He notes a flicker in the surface of the brass and turns to see the Master of Ceremonies, Johannes Burchard, standing in the doorway, come, as tradition demands, to help him dress should he require it and to measure the new pope’s finger so that the goldsmith can start work straight away on the papal ring. He has known a couple of cardinals who walk into conclave with their own ready-made fisherman’s ring in their pocket, just in case. But over the years Rodrigo Borgia has grown to have too much respect for God – or perhaps it is that other deity, Fortuna – to take such chances.

If the bony-faced German is pleased or displeased at the Spaniard’s elevation, he doesn’t show it. His job is also his natural talent: to note everything and express nothing. They have things in common these two men: they are both foreigners at the court of Rome, and both skilled at negotiating the right price for the right job. (Ten years ago, four hundred ducats had been an excellent bid for the post of master of ceremonies – it would cost him triple that now.) Yet in the fifteen years that they have known each other they have exchanged no more words than their roles demanded. Now they will be joined together for as long as they live. Before the new pope can speak, the German falls to his knees and prostrates himself on the ground, judging perfectly the distance in order to kiss the other man’s naked, and mercifully clean, feet. The Master of Ceremonies at work.

The Cardinal of Valencia – and it is the last time anyone will think of him thus – feels a deep glow of pleasure rising up inside him. He picks up his skirts and walks out towards the public balcony.

Sixty-one years old. How many years does he have in front of him? By his age four of the five popes he had served were already rotting in their tombs. But the Borgias have more staying power. His uncle, Calixtus III, had survived to almost eighty. Sixty-one. Three sons, a ripening daughter and a sublime young mistress, young enough to drop more fruit. Borgia blood. Thick with ambition and determination. How long does he need? Give him another… ten – no, fifteen – summers and he will have the bull crest emblazoned over half of Italy.

He strides out on to the balcony into the light of a new day. The crowd roars its greeting. But as Pope Alexander VI lifts his hands to offer the traditional blessing, silence falls. The clothes have become the man.

Bought from Mantua, where those who know say the Gonzaga dukes breed better Turkish stallions than the Turks themselves, the Borgia horse and its messenger are making excellent progress.

The journey from Rome to Siena is harder than its distance warrants. Once outside the great walls of the city the route becomes as treacherous for humans as for animals. Before the coming of Our Lord, when men knew no better than to worship an army of badly behaved gods, the countryside around Rome was legendary for its fertility, with well-kept roads filled with carts and produce pouring into the city’s markets. But over centuries of the true faith, it has degenerated into wilderness and brigandry, divvied up between the families of the great Roman barons; men hidden inside castles and fortresses who would prefer to carry on slaughtering each other than create stability together.

Still, to be robbed and murdered, the victim has to be caught first. And this rider, a young man born in the saddle with a passion to make his mark on the ground, stops for no one and nothing. The heat rises with the sun, but as long as he keeps moving the sweat on his clothes stays cool in the wind he creates. The more he sweats, the further he can ride without needing to empty his bladder. It is past ten o’clock when he reaches Viterbo, inside the borders of the northern papal state. The staging-post is one that the Vice-Chancellor’s postal system has used for years, and it has been on standby since the conclave convened. The stable master himself does the handover of horses. No point in trying to read the boy’s face: there is nothing there but grime and exhaustion; when the sealed letter had been given, Pedro Calderón did not know and neither did he ask. It would not do for the cardinal’s eldest son to remain in ignorance while others celebrated or commiserated on his behalf, and those who work for the Borgias learn fast what is to be gained from doing what you are told.

Back on the road, the new mount is skittish at first, but they come to understand each other’s rhythm fast enough. He rides through the furnace of the day and by mid-afternoon he is soaked with sweat as he climbs the curling road up towards the city gates of Siena. From woodlands and scattered hamlets he is suddenly enveloped into a maze of dirt alleys, alive with other horses, some ridden, some being led. In August, Siena is a giant stable filled with snorting pure-breds on their way to the exercise tracks. Carts and merchants, even the best-dressed of men, make way for them. The city is high on the perfume of horse sweat and excrement, the alleys ankle-thick in leftover dung. In less than a week, the best race horses in Tuscany will be stampeding round the great piazza in a storm of dust and straw; a chariot race without the chariots, mowing down anyone or anybody who gets in their way. On street corners money changes hands under long sleeves. The frenzy of the Palio is everywhere. Cesare Borgia, who should by rights be finishing his studies in Pisa, is as mad for hunting and sport as the next rich young man, and has two horses with a good chance of taking the prize.

They are resting in the stables now, enjoying better treatment than most of the human population of Siena. They train each morning at dawn, which fits in perfectly with their owner’s lifestyle, for recently the newly appointed young Bishop of Palomar has taken to entering the day when it is almost over, then working – and playing – through the night while others sleep. And since what is good for the master is also good for his men, the house is snoring when the rider arrives, the only people up and about a few servants and the old stable guard who acts as watchman.

‘You’ll have to come back. We don’t take visitors till after six p.m.’

In answer the great horse snorts in the man’s face, steam rising off its flanks.

‘I am ridden from Rome on urgent business.’

Begrudgingly, the old man hauls open the doors on to a silent inner courtyard.

‘Where is your master?’

‘Asleep.’

‘Then wake him.’

‘Hoa! I am sixty-five years old and want to reach sixty-six. You wake him. No. On second thoughts, even that would have me gutted and fried.’

From the corner a door opens on a short, half-dressed figure, thick-chested and with a latticework of healed wounds on his upper torso and a face so scarred that it looks as if it has been sliced into bits and rearranged carelessly.

‘Miguel da Corella?’ The boy’s voice is hoarse with dust, or it might be trepidation for the man has a reputation more colourful than his scars. ‘I am ridden from Rome,’ he adds hurriedly in Catalán.

‘When?’

‘Just before dawn.’ He slides from the horse, a cloud of dirt rising around him. He thrusts out a gloved hand and they clasp each other by the wrist, once, twice. ‘With no one behind me.’

‘You can ride, boy. You’re Pedro Calderón, yes? Romano’s son.’

Their language is rough and ready, a long way from home with the touch of gang talk. The boy nods, pleased beyond measure that he is known.

‘Where is it, then?’

From inside his jerkin, the young man pulls out a leather pouch, dark with sweat.

‘I’ll take it.’

The rider shakes his head. ‘I… my instructions are to put it into his hands only, Michelotto.’ He risks the popular name, used by those who love him. And hate him.

‘You already have.’ The man holds out his palms. ‘These belong to him, boy.’

Still the rider doesn’t move.

‘Dawn, eh? All right.’ He gestures to a door on the first floor. ‘But you shout before you go in and keep your eyes down. He’s not alone.’

Halfway up the stairs the rider finds his legs buckling. He hauls himself up by the banister, biting back the cramp. Two years in the service of Vice-Chancellor Borgia, two years of cross-country deliveries and the odd piece of thuggery to get to this. Of course he has seen Cesare Borgia, but in company, never to meet directly. He knows something of the others, one Spanish family to another, but this inner circle is something else.

‘My Lord Cesare!’

He lifts his hands to smash on the door, but it is already open in his face, the sword coming so close to his ear that he wonders if he’ll ever hear again.

‘Rome, my lord,’ he squeaks, flinging up his arms in surrender. ‘I bring news from Rome.’

‘God’s wounds. You climb stairs like a bullock, man.’ The other arm grabs him and pulls him inside as Michelotto’s laughter rises up from below.

Cesare takes the offered pouch and turns his back, the door left open for the light, the boy already forgotten. He breaks the seal and unfolds the paper. The room smells of sex, sweet and sour. Pedro stands transfixed. He cannot take his eyes off him: this man who can cleave through a bull’s neck with a single blow and jump between galloping horses. Or so they say. They say he makes Michelotto ram his fist into his abdomen every morning to test the metal in the muscles. They say… But then they say so many things.

In the golden light of the afternoon the body looks as tender as it is strong: the sheen of sweat along the muscles of the upper torso, the scattering of hair around the nipples, the taut stomach and the vulnerable hollow inside the hip as it dips towards the groin and the tucked sheet. With his head bent over the words it is possible to make out the shape of a small, ill-kept tonsure amid the mane of hair. Everyone knows, yet it still comes as a shock. When the angels look down on him, are they equally perplexed to think of Cesare Borgia as a man of the Church? While youth is blithely immune to the threat of age, the thickening flesh, the dulling of the glow, young men judge each other’s bodies with clear enough eyes and they know when they are outclassed. It is not only the athletic beauty; it is the very way he holds himself, aware and unaware at the same time, as if the world exists only to wait on him when he is ready. Power bought or power born? Pedro feels a shiver of excitement even at the question.

Cesare’s face is impassive as he reads. Not a twitch or a breath, even the eyelids lizard-still. From somewhere in the gloom comes a cooing noise; something willing and lovely is turning over, beginning to wake. Too late Pedro remembers the order to keep his eyes down. He snaps his head to the floor. The cooing subsides. He waits. And waits.

Then, without his hearing any footsteps, Cesare is in front of him again.

‘You will never deliver a sweeter letter in your life,’ he says, his voice now loud enough to be heard far outside the room.

From the courtyard below Michelotto lets out a howling whoop.

<Date: 2015-01-11; view: 1153

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| DEBRIEFING OF THE CASUALTIES/WITNESSES | | | A General Scheme of Analysis |