CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

THE TRUE MEANING OF THE HAU OF VALUABLES

I am not a linguist, a student of primitive religions, an expert on the Maori, or even a Talmudic scholar. The "certainty" I see in the disputed text of Tamati Ranapiri is therefore suggested with due reservations. Still, to adopt the current structuralist incantation, "everything happens as if" the Maori was trying to explain a religious concept by an economic principle, which Mauss promptly understood the other way around and thereupon proceeded to develop the economic principle by the religious concept. The hau in question really means something on the order of "return on" or "product of," and the principle expressed in the text on taonga is that any such yield on a gift ought to be handed over to the original donor.

The disputed text absolutely should be restored to its position as an explanatory gloss to the description of a sacrifical rite.8

8. There is a very curious difference between the several versions of Best, Mauss, and Tamati Ranapiri. Mauss appears to deliberately delete Best's reference to the ceremony in the opening phrase. Best had cited " T will now speak of the hau, and the ceremony of whangai hau'"; whereas Mauss has it merely, "\Je vais vous [sic] parler du hau... *" (ellipsis is Mauss's). The interesting point is raised by Biggs's undoubtedly authentic translation, much closer to that of Mauss, as it likewise does not mention whangai hau at this point: **'Now, concerning the hau of the forest*" However, even in this form the original text linked the message on taonga with the ceremony of whangai hau, "fostering" or "nourishing hau, "since the hau of the forest was not the subject of the immediately succeeding passage on gifts but of the consequent and ultimate description of the ceremony.

Tamata Ranapiri was trying to make Best understand by this example of gift exchange—example so ordinary that anybody (or any Maori) ought to be able to grasp it immediately—why certain game birds are ceremoniously returned to the hau of the forest, to the source of their abundance. In other words, he adduced a transaction among men parallel to the ritual transaction he was about to relate, such that the former would serve as paradigm for the latter. As a matter of fact, the secular transaction does not prove directly comprehensible to us, and the best way to understand it is to work backwards from the exchange logic of the ceremony.

This logic, as presented by Tamati Ranapiri, is perfectly straightforward. It is necessary only to observe the sage's use of "mauri" as the physical embodiment of the forest hau, the power of increase—a mode of conceiving the mauri that is not at all idiosyncratic, to judge from other writings of Best. The mauri, housing the hau, is placed in the forest by the priests (tohunga) to make game birds abound. Here then is the passage that followed that on the gift exchange—in the intention of the informant, as night follows day:'

I will explain something to you about the forest hau. The mauri was placed or implanted in the forest by the tohunga [priests]. It is the mauri that causes birds to be abundant in the forest, that they may be slain and taken by man. These birds are the property of, or belong to, the mauri, the tohunga, and the forest: that is to say, they are an equivalent for that important item, the mauri. Hence it is said that offerings should be made to the hau of the forest. The tohunga (priests, adepts) eat the offering because the mauri is theirs: it was they who located it in the forest, who caused it to be. That is why some of the birds cooked at the sacred fire are set apart to be eaten by the priests only, in order that the hau of the forest-products, and the mauri, may return again to the forest—that is, to the mauri. Enough of these matters (Best, 1909, p. 439).

In other words, and essentially: the mauri that holds the increase-power (hau) is placed in the forest by the priests (tohunga);the mauri causes game birds to abound; accordingly, some of the captured birds should be ceremoniously returned to the priests who placed the mauri; the consumption of these birds by the priests in effect restores the fertility (hau) of the forest (hence the name of the ceremony, whangai hau, "nourishing hau").10

9. I use Best's translation, the one available to Mauss. I also have in hand Biggs's interlinear version; it does not differ significantly from Best's.

10. The earlier discussion of this ritual, preceeding the passage on taonga in the full Maori text, in fact comments on two related ceremonies: the one just described and another, performed before, by those sent into the forest in advance of the fowling season to observe the state of the game. I cite the main part of this earlier description in Biggs's version: "The hau of the forest has two 'likenesses.' 1. When the forest is inspected by the observers, and if birds are observed to be there, and if birds are killed by them that day, the first bird killed by them is offered to the mauri. It is simply thrown away into the bush, and is said, 'that's for the mauri. * The reason, lest they get nothing in the future. 2. When the hunting is finished (they) go out of the bush and begin to cook the birds for preserving in fat. Some are set aside first to feed the hau of the forest; this is the forest hau. Those birds which were set aside are cooked on the second fire. Only the priests eat the birds of the second fire, Other birds are set aside for the tapairu from which only the women eat. Most of the birds are set aside and cooked on the puuraakau fire. The birds of the puuraakau fire are for all to eat. . . ." (cf. Best, 1909, pp. 438, 44(M1, 449f; and for other details of the ceremonies, 1942, pp. 13, 184f, 316-17).

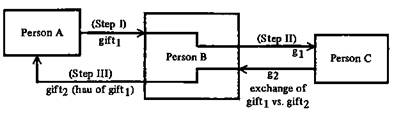

Immediately then, the ceremonial transaction presents a familiar appearance: a three-party game, with the priests in the position of an initiating donor to whom should be rendered the returns on an original gift. The cycle of exchange is shown in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1

Now, in the light of thip transaction, reconsider the text, just preceding, on gifts among men. Everything becomes transparent. The secular exchange of taonga is only slightly different in form from the ceremonial offering of birds, while in principle it is exactly the same— thus the didactic value of its position in Ranapiri's discourse. A gives a gift to B who transforms it into something else in an exchange with C, but since the taonga given by C to B is the product (hau) of A's original gift, this benefit ought to be surrendered to A. The cycle is shown in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2

The meaning of hau one disengages from the exchange of taonga is as secular as the exchange itself. If the second gift is the hau of the first, then the hau of a good is its yield, just as the hau of a forest is its productiveness. Actually, to suppose Tamati Ranapiri meant to say the gift has a spirit which forces repayment seems to slight the old gentleman's obvious intelligence. To illustrate such a spirit needs only a game of two persons: you give something to me; your spirit (hau) in that thing obliges me to reciprocate. Simple enough. The introduction of a third party could only unduly complicate and obscure the point. But if the point is neither spiritual nor reciprocity as such, if it is rather that one man's gift should not be another man's capital, and therefore the fruits of a gift ought to be passed back to the original holder, then the introduction of a third party is necessary. It is necessary precisely to show a turnover: the gift has had issue; the recipient has used it to advantage. Ranapiri was careful to prepare this notion of advantage beforehand by stipulating11 the absence of equivalence in the first instance, as if A had given 2?a free gift. He implies the same, moreover, in stressing the defray between the reception of the gift by the third person and the repayment—"a long time passes, and that man thinks that he has the valuable, he should give some repayment to me." As Firth observes, delayed repayments among Maori are customarily larger than the initial gift (1959a, p. 422); indeed, it is a general rule of Maori gift exchange that, "the payment must if possible be somewhat in excess of what the principle of equivalence demanded" (ibid., p. 423). Finally, observe just where the term hau enters into the discussion. Not with the initial transfer from the first to the second party, as well it could if it were the spirit in the gift, but upon the exchange between the second and third parties, as logically it would if it were the yield on the gift.12

11. And in Best's translation, even reiterating: "'Suppose that you possess a certain article, and you give that article to me, without price. We make no bargain over it.'"

12. Firth cites the following discussion to this point from Gudgeon: '"If a man received a present and passed it on to some third person then there is no impropriety in such an act; but if a return present is made by the third party then it must be passed on to the original grantor or it is a hau ngaro (consumed hau)'" (Firth, 1959a, p. 418). The lack of consequence in the first of these conditions is again evidence against Mauss's nostalgic hau, ever striving to return to its foyer.

The term "profit" is economically and historically inappropriate to the Maori, but it would have been a better translation than "spirit" for the hau in question.

Best provides one other example of exchange in which hau figures. Significantly, the little scene is again a transaction a trois:

I was having a flax shoulder-cape made by a native woman at Rua-tahuna One of the troopers wished to buy it from the weaver, but she firmly refused, lest the horrors of hau whitia descend upon her. The term hau whitia means "averted hau" (1900-1901, p. 198).

Only slightly different from the model elaborated by Tamati Rana-piri, this anecdote offers no particular difficulty. Having commissioned the cape, Best had the prior claim on it. Had the weaver accepted the trooper's offer, she would have turned this thing to her own advantage, leaving Best with nothing. She appropriates the product of Best's cape; she becomes subject to the evils of a gain unrightfully turned aside, "the horrors of hau whitia."" Otherwise said, she is guilty of eating hau—kaihau—for in the introduction to this incident Best had explained,

Should I dispose of some article belonging to another person and not hand over to him any return or payment I may have received for that article, that is a hau whitia and my act is a kai hau, and death awaits, for the dread terrors of makutu [witchcraft] will be turned upon me (1900-1901, pp. 197-98)14

13. Whitia is the past participle of whiti. Whili, according to H. Williams's dictionary, means: (1) v.i., cross over, reach the opposite side; (2) change, turn, to be inverted, to be contrary; (3) v./., pass through; (4) turn over, prise (as with a lever); (5) change (Williams, 1921, p. 584).

14. Best's further interpretation lent itself to Mauss's views: "For it seems that that article of yours is impregnated with a certain amount of your hau, which presumably passes into the article received in exchange therefore, because if I pass that second article on to other hands it is a hau whitia"(1900-1901, p. 198). Thus "it seems." One has a feeling of participating in a game of ethnographic folk-etymology, which we now find, from Best's explanation, is a quite probable game a quatre.

So as Firth observed, the hau (even if it were a spirit) does not cause harm on its own initiative; the distinct procedure of witchcraft (makutu) has to be set in motion. It is not even implied by this incident that such witchcraft would work through the passive medium of hau, since Best, who was potentially the deceived party, had apparently put nothing tangible into circulation. Taken together, the different texts on the hau of gifts suggest something else entirely: not that the goods withheld are dangerous, but that withholding goods is immoral—and therefore dangerous in the sense the deceiver is open to justifiable attack. " 'It would not be correct to keep it for myself,' said Ranapiri, " 'I will become mate (ill, or die).' "

We have to deal with a society in which freedom to gain at others' expense is not envisioned by the relations and forms of exchange. Therein lies the moral of the old Maori's economic fable. The issue he posed went beyond reciprocity: not merely that gifts must be suitably returned, but that returns rightfully should be given back. This interpretation it is possible to sustain by a judicious selection among the many meanings of hau entered in H. Williams's (1921) Maori dictionary. Hau is a verb meaning to "exceed, be in excess," as exemplified in the phrase kei te hau te wharika nei ("this mat is longer than necessary"); likewise, hau is the substantive, "excess, parts, fraction over any complete measurement." Hau is also "property, spoils." Then there is haumi, a derivative meaning to "join," to "lengthen by addition," to "receive or lay aside"; it is also, as a noun, "the piece of wood by whith the body of a canoe is lengthened."

The following is the true meaning of Tamati Ranapiri's famous and enigmatic discourse on the hau of taonga:

I will explain it carefully to you. Now, you have something valuable which you give to me. We have no agreement about payment. Now, I give it to someone else, and, a long time passes, and that man thinks he has the valuable, he should give some repayment to me, and so he does so. Now, that valuable which was given to me, that is the product of [hau] the valuable which was given to me[by you] before. I must give it to you. It would not be right for me to keep it for myself, whether it be something good, or bad, that valuable must be given to you from me. Because that valuable is a return on [hau] the other valuable. If I should hang onto that valuable for myself, I will become ill [or die]."

Date: 2014-12-21; view: 1287

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| The Commentaries of Levi-Strauss, Firth and Johansen | | | ASIDE ON THE MAORI SORCERER'S APPRENTICE |