CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Theoretically November to March, but see Richards, 1962, p. 390.

18. Richards's comments on the duration of the working day provide additional pertinent information: "Bemba rise at 5 a.m. in the hot weather, but come reluctantly from their huts at 8 or even later in the cold season, and their working day is fixed accordingly ... the Bemba in his unspecialized society does different tasks daily and a different amount of work each day. The diary of men's and women's activities . . . shows that in Kampamba the men were employed on five quite separate occupations ... in the course often days, and at Kasaka ... various ritual observances, visits from friends or Europeans, interrupted the daily routine constantly. Domestic needs tie the women to certain daily tasks . . . but even then their garden work varies greatly from day to day. The working hours also change in what seems to us a most erratic manner. In fact I do not think the people ever conceive of such periods as the month, week, or day in relation to regular work at all.... The whole bodily rhythm of the Bemba differs completely from that of a peasant in Western Europe, let alone an industrial worker. For instance at Kasaka, in a slack season, the old men worked 14 days out of 20 and the young men seven; while at Kampamba in the busier season, the men of all ages worked on an average of 8 out of 9 working days [Sunday not included]. The average working day in the first instance was 2-3/4 hours for men and 2 hours gardening plus 4 hours domestic work for the women, but the figures varied from 0 to 6 hours a day. In the second case the average was 4 hours for the men and 6 for the women, and the figures showed the same daily variation" (1962, pp. 393-394).

Table 2.4. Distribution of activities: Kasaka Village, Bemba (after Richards, 1962, Appendix E)*

| Men (n = 19) | Women (n = 19) | |

| 1. Days mainly working t | garden work, hunting, fishing, crafts, housebuilding, work for Europeans . . . 220 (50%) | gardening, fishing, work for chiefs, work for Europeans, etc . . . 132 (30.3%) |

| Mean duration of full working day | 4.72 hrs/day | 4.42 hrs/day |

| 2. Days of part-time workt | "in village," "away,** "at home" ... 22 (5%) | "in village," "no garden work," "away" ... 153 (35.19%) |

| 3. Days mainly not working | "leisure, "'visits to relatives, § beer-drinks ... 196 (44.5%) | "leisure," visits to relatives, beer-drinks .. . 138(31.7%) |

| 4. Illness | carrying sick ... 2 (0.5%) | confinement... 13 (3%) |

*N = 38; days tabulated = 23.

t The categories 1-4 and classification of data under these rubrics are my own.

$ Richards specifies that even when remaining in the village, women do much domestic work; therefore, she rarely uses the category "leisure" to describe their days, preferring instead "no garden work." "Leisure" on the other hand means "a day spent in sitting, talking, drinking, or doing handicrafts." I have thus put "no garden work" (as well as "in village," "at home" and, for want of further information, "away") in a category of "part-time work," while "leisure" is classed in the category "days mainly not working." "Leisure" includes Christian Sundays.

§ Richards indicates that "walks" in her table mean 'Visits to relatives" unless otherwise specified; I include such "walks" here.

If these tables for the Bemba could be extended over a full year, they would probably yield results similar to those obtained by Guil-lard (1958) for the Toupouri of North Cameroon, shown in Table 2.6."

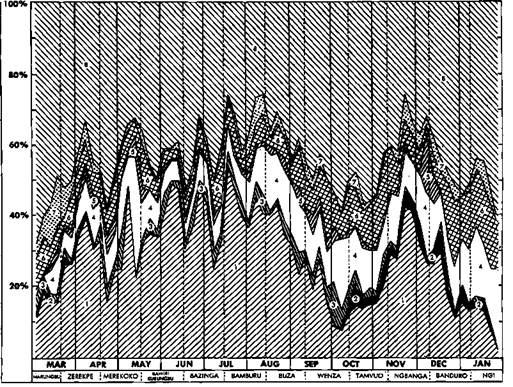

And if such systems as the Bemba and Toupouri were plotted graphically over the year, they would probably resemble the diagrams de Schlippe accumulated for the Azande—one of these is presented in Figure 2.2.

But work schedules such as these, with their generous reservations of time to fete and repose, should not be interpreted from the anxious vantage of European compulsions.20 The periodic deflection from "work" to "ritual" by peoples such as the Tikopians or Fijians, must be made without prejudice, for their linguistic categories know no such distinction, but conceive both activities sufficiently serious as to merit a common term (so the "Work of the Gods"). And what are we to construe of those Australian Aborigines—the Yir Yiront—who do not discriminate between "work" and "play"? (Sharp, 1958, p. 6)

19. Cf. the analogous report from the Cameroons cited by Clark and Haswell (1964, p. 117).

20. "A strange delusion possesses the working classes of the nations where capitalist civilization holds its sway. This delusion drags in its train the individual and social woes which for two centuries have tortured sad humanity. This delusion is the love of work, the furious passion for work, pushed even to the exhaustion of the vital force of the individual and his progeny. Instead of opposing this mental aberration, the priests, the economists and the moralists have cast a sacred halo overwork" (Lafargue, 1909, p. 9).

Table 2.5, Distribution of activities: Kampana Village, Bemba (after Richards, 1962, Appendix E)*

| Men (n = 16, 10 days) | Women (n = 17, 7 days) | |

| 1. Days mainly working | 114(70.8%) | 66 (62.9%) |

| 2. Days of part-time work | 9 (5.6%) | 21 (20%) |

| 3. Days mainly not working | 29 (18%) | 17 (16.2%) |

| 4. Illness | 9(5.6%) | 1 d%) |

* For explanation of the categories adopted, see Table 2.4.

Table 2.6. Distribution of activities over year, Toupouri (after Guillard 1958)*

| Men (n = 11) | Women (n = 18) | |||||

| A verage Man-Days per Year | A verage Man-Days per Year | |||||

| Number | Percent | Range | Number | Percent | Range | |

| Agriculture | 105.5 | 28.7 | 66.5-155.5 | 82.1 | 22.5 | 42-116.5 |

| Other work | 87.5 | 23.5 | 47-149 | 106.6 | 29.0 | 83-134.5 |

| Rest and non-pioductive t | 161.5 | 44.4 | 103.5-239 | 164.4 | 45.2 | 151-192 |

| Illness | 9.5 | 2.6 | 0-30 | 3.0 |

*N = 29 working persons.

t Category includes marketing and visits (often indistinguishable), feasts and rituals, and repose. It is not absolutely clear that for men the time in hunting and fishing was excluded here. Women's days in the village were calculated by Guillard as one-half "other work," one-half rest.

Perhaps equally arbitrary are many cultural definitions of inclement weather, serving as pretext, it seems, for suspending production under conditions somewhere short of the human capacity for discomfort. Yet it would be insufficient simply to suppose that production is thus subject to arbitrary interference: to interruption by other obligations, themselves "noneconomic" but not by that character unworthy of people's respect. These other claims—of ceremony, diversion, sociability and repose—are only the complement or, if you will, the super-structural counterpart of a dynamic proper to the economy. They are not simply imposed upon the economy from without, for there is within, in the way production is organized, an intrinsic discontinuity. The economy has its own cutoff principal: it is an economy of concrete and limited objectives.

Consider the Siuai of Bougainville. Douglas Oliver describes in terms by now familiar how garden work submits to diverse cultural obstructions, leaving the real output clearly below the possible:

There is, of course no physical reason why this labor output could not be increased There is no serious land-shortage, and a labor "stretch-out" could be and often is undertaken. Siuai women work hard at their gardens but not nearly so hard as some Papuan women; it is conceivable that they could work much longer and harder without doing themselves physical injury. That is to say, it is conceivable by other standards of work. Cultural rather than physical factors influence Siuai standards of "maximum working hours." Garden work is taboo for long periods following upon death of a kinsman or friend. Nursing mothers may spend but a few hours daily away from their babies, who, because of ritual restrictions, often may not be carried into the gardens. And aside from these ritual restrictions upon continuous garden work, there are less spectacular limitations. It is conventional to cease working during even light showers; it is customary to start for the garden only after the sun is well up, and to leave for home in mid-afternoon. Now and then a married couple will remain in their garden site all night sleeping in a lean-to, but only the most ambitious and enterprising care to discomfort themselves thus (Oliver, 1949 [3], p. 16).

But in another connection Oliver explains more fundamentally why Siuai working standards are so modest—because, except for politically ambitious people, they are sufficient:

As a matter of fact, natives took pride in their ability to estimate their immediate personal consumption needs, and to produce just enough taro to satisfy them. I write "personal consumption needs" advisedly, because there is very little commercial or ritual exchange of taro. Nevertheless, personal consumption needs vary considerably: there is a lot of difference between the amount of taro consumed by an ordinary man with his one or two pigs, and an ambitious social-climber with his ten or twenty. The latter has to cultivate more and more land in order to feed his increasing number of pigs and to provide vegetable food for distribution among guests at his feasts (Oliver, 1949 [4], p. 89).

Figure 2.2, Annual Distribution of Activities, Azande [Green Belt] (after de Schlippe, 1956)

1. Agricultural work.

2. Gathering of wild produce, including honey, chillies, mushrooms, caterpillars, berries, roots, salt grass, and divers others.

3. Hunting and fishing.

4. Processing at home of agricultural produce and of produce of gathering, including beer brewing, oil and salt making, and so on. These four items taken together could be called food production at or near home.

5. Marketing, including cotton markets, as well as weekly food markets, either selling or buying, and absences for the purpose of acquiring tools, clothes, and other goods in shops or elsewhere.

6. Other occupations at home, mainly housebuilding and craftsmanship, but also repairing, putting things in order, and such like.

7. Work outside home, including hunting and fishing expeditions, work for chief or district,-salaried work for Government or E.P.B., and work for neighbors in beer parties.

8. No work for various reasons—including chiefs' courts, ceremonies and rituals, sickness at ’home, in hospital or at the witchdoctor's, childbirth, rest, and leisure.

The graph does not represent man-days given to various tasks but the number of days (or percentage of days) the type of activity occurred.

Production has its own constraints. If these are sometimes manifest as the deployment of labor to other ends, it should not be thus obscured to the analysis. Sometimes it is not even disguised to observation: as of certain hunters, for example, who once again become the revealatory case because they seem to need no excuse to stop working once they have enough to eat.21

21. See the reference to McCarthy and MacArthur's study of Australian hunting in Chapter 1. "The quantity of food gathered in any one day by any of these groups could in every instance be increased...." Woodburn writes to the same effect of the Hadza: "When a man goes off into Ihe bush with his bow and arrows, his main interest is usually to satisfy his hunger. Once he has satisfied his hunger by eating berries or by shooting and catching some small animal, he is unlikely to make much effort to shoot a large animal… Men most often return from the bush empty-handed but with their hunger satisfied" (1968, p. 53; cf. p. 51). Women, meanwhile, are doing essentially the same.

All this can be phrased another way: from the point of view of the existing mode of production, a considerable proportion of the available labor-power is excess. And the system, having thus defined sufficiency, does not realize the surplus of which it is perfectly capable:

There is no doubt at all that the Kuikuru could produce a surplus of food over the full productive cycle. At the present time a man spends only about 3-1/2 hours a day on subsistence—2 hours on horticulture, and 1-1/2 hours on fishing. Of the remaining 10 or 12 waking hours of the day the Kuikuru men spend a great deal of it dancing, wrestling, in some form of informal recreation, and in loafing. A good deal more of this time could easily be devoted to gardening. Even an extra half hour a day spent on agriculture would enable a man to produce a substantial surplus of manioc. However, as conditions stand now there is no reason for the Kuikuru to produce such a surplus, nor is there any indication that they will (Carneiro, 1968, p. 134).

In brief, it is an economy of production for use, for the livelihood of the producers. Having come to this conclusion, our discussion links up with established theory in economic history. It also makes connection with understandings long established in anthropological economics. Firth had effectively made this point in 1929, when commenting on the discontinuity of Maori labor in comparison with European tempos and incentives (1959a, p. 192 f). In the 1940's Gluckman wrote as much about the Bantu in general and the Lozi in particular (1943, p. 36; cf. Leacock,1954, p. 7).

There will be much more to say theoretically about domestic production for use. For now I rest on the descriptive comment that in primitive communities an important fraction of existing labor resources may be rendered excessive by the mode of production.

Date: 2014-12-21; view: 1179

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| UNDERUSE OF LABOR-POWER | | | HOUSEHOLD FAILURE |