CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

The Laos Crisis, 1960–1963

The first foreign policy crisis faced by President-elect John F. Kennedy was not centered in Berlin, nor in Cuba, nor in the islands off the Chinese mainland, nor in Vietnam, nor in any of the better-known hot spots of the Cold War, but in landlocked, poverty stricken Laos. This was the major issue Kennedy and his foreign policy team—Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, and National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy—focused on during the days leading up to Kennedy’s inauguration on January 20, 1961.

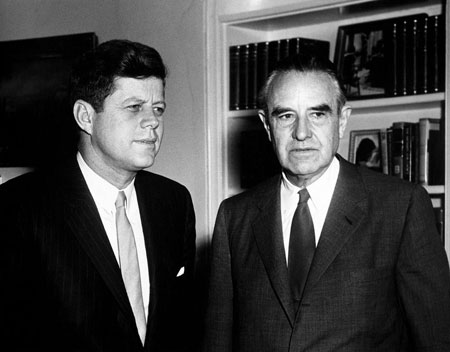

President Kennedy meets with Ambassador at Large Averell Harriman in the Oval Office, March 29, 1961. (Abbie Rowe. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston)

Kennedy met with President Eisenhower the day before his inauguration with two goals in mind. He expected the meeting to “serve a specific purpose in reassuring the public as to the harmony of the transition. Therefore strengthening our hand.” His substantive focus was on Laos. “I was anxious,” he recounted to his secretary, “to get some commitment from the outgoing administration as to how they would deal with Laos which they were handing to us. I thought particularly it would be useful to have some idea as to how prepared they were for intervention.”

The Eisenhower administration was leaving Kennedy a confused, complex, and intractable situation. Laos was a victim of geography: a RAND study of the period summarized the nation as “Hardly a nation except in the legal sense, Laos lacked the ability to defend its recent independence. Its economy was undeveloped, its administrative capacity primitive, its population divided both ethnically and regionally, and its elite disunited, corrupt, and unfit to lead.” But this surpassingly weak state was the “cork in the bottle,” as Eisenhower summarized in his meeting with Kennedy; the outgoing President expected its loss to be “the beginning of the loss of most of the Far East.”

The Eisenhower administration had worked for years to create a strong anti-Communist bastion in Laos, a bulwark against Communist China and North Vietnam. While attractive on a map, this strategy was completely at odds with the characteristics of the Laotian state and people. By 1961, Laos was fragmented politically, with three factions vying for control. The United States had thrown its support behind General Nosavan Phoumi, whose forces were engaged in combat with a neutralist force under Kong Le. Soviet aircraft were conducting resupply missions for Kong Le’s forces. Neutralist leader and former Prime Minister Souvanna Phouma had gone into exile in Cambodia, but remained influential and active in Laotian politics. His half-brother, Souphanouverong, led the Communist-dominated Pathet Lao, which had established control over an extensive area along the Laos-North Vietnam border. Phoumi’s forces had little popular support, had proven ineffective in combat, and appeared to be well on their way to a military defeat.

The Eisenhower administration had led the creation of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization for precisely this sort of contingency. In this first major test, however, the United States was unable to secure the alliance’s support for intervention. Its major European powers, Great Britain and France, considered Phoumi an illegitimate ruler and supported Souvanna Phouma; they were adamantly opposed to taking military action in Laos. An interagency analysis prepared in January 1961 summarized, “Since SEATO was created to act in circumstances such as that now existing in Laos but has not acted, it casts doubt not only on its own credibility but on the reliability of the United States as its originator . . . SEATO becomes a means by which restraint is imposed on us by our allies.” As the Eisenhower administration reached its final days, the United States was faced with the prospect of unilateral military intervention in a desperate attempt to salvage the situation. Beyond the vast logistics issues associated with intervention, the insertion of U.S. forces raised the substantial risk of a U.S.-Soviet military confrontation.

Kennedy faced a choice between two unpromising strategies: pursue a military solution, very likely demanding a unilateral intervention by U.S. forces; or adapt a major shift in policy, seeking a cease-fire and a neutralization of Laos. He rejected the military option, though he encouraged an offensive by Phoumi designed to strengthen his negotiating position. It failed abjectly. Kennedy opened his press conference on March 23, 1961, with an extended discussion of Laos, calling for an end to hostilities and negotiations leading to a neutralized and independent Laos. The Pathet Lao accepted the ceasefire offer on May 3. This delay gave the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) the time to conduct an offensive in southern Laos, capturing the crossroad village of Tchepone and the terrain necessary to extend the Ho Chi Minh Trail to the western side of the Annamite Mountains on the border between Laos and South Vietnam. Laos was a major topic at the Vienna Summit on June 4, with Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khruschev agreeing on a common goal of a ceasefire, neutrality, and a coalition government; as Khruschev summarized, “the basic question is to bring about agreement among the three forces in Laos, so that the formation of a truly neutral government could be secured.” Kennedy considered Laos a test case for the prospects of U.S.-Soviet cooperation, in areas where the superpowers could reach common objectives and avoid confrontation.

Kennedy appointed W. Averell Harriman as Ambassador at Large in the first days of his administration, and then formalized Harriman’s policy role in appointing him Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs the following November. Harriman took the lead in orchestrating American policy toward Laos as an international conference on Laos convened in Geneva on May 16. The fourteen nations involved included the U.S.S.R., Laos, People’s Republic of China, North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Poland, the United States, France, the United Kingdom, India, Burma, Cambodia, Canada, and Thailand. Meanwhile the three Laotian factions conducted negotiations on the composition of a coalition government. By the following March Harriman had become disenchanted with Phoumi, and decisively shifted American policy toward a coalition government led by Souvanna Phouma. The Laotian groups reached agreement on the composition of the coalition government on June 12, 1962, and the Geneva conference reached agreement on the Declaration on the Neutrality of Laos on July 23.

These agreements provided for a coalition government in Laos under Souvanna Phouma, with cabinet positions distributed among the three factions. The Declaration on the Neutrality of Laos and its associated protocols called for the withdrawal of all “foreign regular and irregular troops, foreign para-military formations and foreign military personnel” under the supervision of the International Commission for Supervision and Control in Laos (ICC), comprised of representatives of India, Poland, and Canada. The ICC would operate on the principle of unanimity, a change from its practice from 1954 to 1958, when it operated under majority rules. Integration and demobilization of the three Laotian armies would be conducted by the coalition government, with neither the ICC nor other international parties overseeing or enforcing these critical activities.

These agreements broke down quickly, with lasting consequences for Laos and its neighbors. The NVA conducted a symbolic withdrawal of 15 troops on August 27, and on October 9 North Vietnam notified the Laotian foreign ministry that their troops had been withdrawn in accordance with the Geneva agreement. However, North Vietnam continued its advisory, logistics, and combat in support of the Pathet Lao in violation of the accords. North Vietnam also continued to extend its territorial control in southern Laos to secure its logistics lines to the battle areas in South Vietnam. The United States withdrew its military advisory teams in compliance with the Geneva agreement, but in its aftermath responded to the North Vietnamese violation by supporting Meo and Thai forces, and by providing economic and military support to the Phouma government and its army.

Date: 2016-01-14; view: 3364

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| The Presidencies of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson | | | The Bay of Pigs Invasion and its Aftermath, April 1961–October 1962 |