CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Edit]The United States

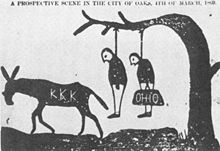

A cartoon threatening that the KKK willlynch carpetbaggers, in the Independent Monitor, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, 1868.

In the 1850s, John Brown (1800–1859) was an abolitionist who advocated and practiced armed opposition to slavery. Brown led several attacks between 1856 and 1859, the most famous in 1859 against the armory at Harpers Ferry. Local forces soon recaptured the fort and Brown was tried and executed fortreason.[42] A biographer of Brown has written that his purpose was "to force the nation into a new political pattern by creating terror."[43]

After the Civil War, on December 24, 1865, six Confederate veterans created the Ku Klux Klan (KKK).[44] The KKK used violence, lynching, murder and acts of intimidation such as cross burning to oppress in particular African Americans, and created a sensation with its masked forays' dramatic nature.[45][46] The group's politics are generally perceived as white supremacy, anti-Semitism, racism, anti-Catholicism, and nativism.[45] A KKK founder boasted that it was a nationwide organization of 550,000 men and that it could muster 40,000 Klansmen within five days' notice, but as a secret or "invisible" group with no membership rosters, it was difficult to judge the Klan's actual size. The KKK has at times been politically powerful, and at various times controlled the governments of Tennessee,Oklahoma, and South Carolina, in addition to several legislatures in the South.[citation needed]

[edit]Europe

In 1867 the Irish Republican Brotherhood, a revolutionary Irish nationalist group,[47] carried out attacks in England.[48] Writer Richard English has referred to such attacks as the first acts of "republican terrorism," which would became a recurrent feature of British and Irish history. The group is considered a precursor to the Irish Republican Army.[49]

Ignaty Gryniewietsky.

Europeans invented "Propaganda of the deed" (or "propaganda by the deed," from the French propagande par le fait) theory, a concept that advocates physicalviolence or other provocative public acts against political enemies in order to inspire mass rebellion or revolution. An early proponent was the Italian revolutionary Carlo Pisacane (1818–1857), who wrote in his "Political Testament" (1857) that "ideas spring from deeds and not the other way around." Anarchist Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876), in his "Letters to a Frenchman on the Present Crisis" (1870) stated that "we must spread our principles, not with words but with deeds, for this is the most popular, the most potent, and the most irresistible form of propaganda."[50] The phrase itself was popularized by the French anarchist Paul Brousse (1844–1912), who in 1877 cited as examples the 1871 Paris Commune and a workers' demonstration in Berne provocatively using the socialist red flag.[51] By the 1880s, the slogan had begun to be used to refer to bombings, regicides and tyrannicides. Reflecting this new understanding of the term, Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta in 1895 described "propaganda by the deed" (which he opposed the use of) as violent communal insurrections meant to ignite an imminent revolution.[52]

Founded in Russia in 1878, Narodnaya Volya (Íàðîäíàÿ Âîëÿ in Russian; People's Will in English) was a revolutionary anarchist group inspired by Sergei Nechayevand "propaganda by the deed" theorist Pisacane.[15][40] The group developed ideas—such as targeted killing of the 'leaders of oppression'—that were to become the hallmark of subsequent violence by small non-state groups, and they were convinced that the developing technologies of the age—such as the invention of dynamite, which they were the first anarchist group to make widespread use of[53]—enabled them to strike directly and with discrimination.[37] Attempting to spark a popular revolt against Russia's Tsars, the group killed prominent political figures by gun and bomb, and on March 13, 1881, assassinated Russia's Tsar Alexander II.[15] The assassination, by a bomb that also killed the Tsar's attacker, Ignacy Hryniewiecki, failed to spark the expected revolution, and an ensuing crackdown brought the group to an end.[54]

Individual Europeans also engaged in politically motivated violence. For example, in 1893, Auguste Vaillant, a French anarchist, threw a bomb in the French Chamber of Deputies in which one person was injured.[55] In reaction to Vaillant's bombing and other bombings and assassination attempts, the French government passed a set of laws restricting freedom of the press that were pejoratively known as the lois scélérates ("villainous laws"). From 1894 to 1896, President of France Marie Francois Carnot, Prime Minister of Spain Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, and Austria-Hungary EmpressElisabeth of Bavaria were killed by anarchists.

[edit]The Ottoman Empire

Several nationalist groups used violence against an Ottoman Empire in apparent decline. One was the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (in Armenian Dashnaktsuthium, or "The Federation"), a revolutionary movement founded in Tiflis (Russian Transcaucasia) in 1890 by Christopher Mikaelian. Many members had been part of Narodnaya Volya or the Hunchakian Revolutionary Party.[56] The group published newsletters, smuggled arms, and hijacked buildings as it sought to bring in European intervention that would force the Ottoman Empire to surrender control of its Armenian territories.[57] On August 24, 1896, 17-year-old Babken Suni led twenty-six members in capturing the Imperial Ottoman Bank in Constantinople. The group unsuccessfully demanded the creation of an Armenian state, but backed down on a threat to blow up the bank. An ensuing security crackdown destroyed the group.[58]

Also inspired by Narodnaya Volya, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) was a revolutionary movement founded in 1893 by Hristo Tatarchev in the Ottoman-controlled Macedonian territories.[59][60] Through assassinations and by provoking uprisings, the group sought to coerce the Ottoman government into creating a Macedonian nation.[61] On July 20, 1903, the group incited the Ilinden uprising in the Ottoman villayet of Monastir. The IMRO declared the town's independence and sent demands to the European Powers that all of Macedonia be freed.[62] The demands were ignored and Turkish troops crushed the 27,000 rebels in the town two months later.[63]

Date: 2015-01-02; view: 1158

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Edit]Before the Reign of Terror | | | Edit]Early 20th century |