CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Instrument description

The revival

"Is the bagpipe played somewhere in Dalarna? And how is it tuned?"

Swedish author August Strindberg in a letter to painter Carl Larsson 1906.

"That horrible instrument is no longer played in Dalarna."

Carl Larsson's answer.

Mats Rehnberg

In 1943 The Nordic museum in Stockholm published a dissertation, "Säckpipan i Sverige" (The Bagpipe in Sweden), by the ethnologist Mats Rehnberg (1915-1984). Rehnberg had found the first hints about a Swedish bagpipe tradition in 1937, through a word in a local dialect in Dalarna[1]. Then, during an evacuation of the Nordic museum's dusty collections in 1939, some strange (and very dry) bagpipes fell out from a box ... Mats Rehnberg

In 1943 The Nordic museum in Stockholm published a dissertation, "Säckpipan i Sverige" (The Bagpipe in Sweden), by the ethnologist Mats Rehnberg (1915-1984). Rehnberg had found the first hints about a Swedish bagpipe tradition in 1937, through a word in a local dialect in Dalarna[1]. Then, during an evacuation of the Nordic museum's dusty collections in 1939, some strange (and very dry) bagpipes fell out from a box ...

Gudmunds Nils Larsson (1892-1949)

Rehnberg made a scoop. It was an established 'fact' at the time that there had never been a bagpipe tradition in Sweden, at least not since mediaeval times - an interesting claim considering that the instrument was mentioned as a national instrument only a few decades before (see quote on the introduction page). Gudmunds Nils Larsson (1892-1949)

Rehnberg made a scoop. It was an established 'fact' at the time that there had never been a bagpipe tradition in Sweden, at least not since mediaeval times - an interesting claim considering that the instrument was mentioned as a national instrument only a few decades before (see quote on the introduction page).

Ture Gudmundsson

Rehnberg visited and interviewed the last known bagpiper, Gudmunds Nils Larsson, several times during his work. So did the music teacher Ture Gudmundsson (1908-1979), who had been inspired by Rehnberg's dissertation to build a bagpipe, but soon found that he needed more technical information. After his visit to Gudmunds Nils Larsson, Gudmundsson managed to make a playable instrument[2] on which he played and recorded two tunes for the Swedish Radio in 1948. For 35 years, this was the only recording of Swedish bagpipes. Ture Gudmundsson

Rehnberg visited and interviewed the last known bagpiper, Gudmunds Nils Larsson, several times during his work. So did the music teacher Ture Gudmundsson (1908-1979), who had been inspired by Rehnberg's dissertation to build a bagpipe, but soon found that he needed more technical information. After his visit to Gudmunds Nils Larsson, Gudmundsson managed to make a playable instrument[2] on which he played and recorded two tunes for the Swedish Radio in 1948. For 35 years, this was the only recording of Swedish bagpipes.

|  19th century bagpipe

A handful of instruments were built in the 50's, 60's and 70's, but it was not until 1981, when Gunnar Ternhag at Dalarna's museum asked Leif Eriksson (a saw-mill worker and cabinet-maker) and Per Gudmundson (a fiddler) to develop a reliable instrument and Eriksson started to produce them in larger quantities that the revival really started. The revived instrument was a compromise between the the few (about a dozen) preserved bagpipes in Swedish museums, and the need for a bagpipe that goes well together with other instruments. 19th century bagpipe

A handful of instruments were built in the 50's, 60's and 70's, but it was not until 1981, when Gunnar Ternhag at Dalarna's museum asked Leif Eriksson (a saw-mill worker and cabinet-maker) and Per Gudmundson (a fiddler) to develop a reliable instrument and Eriksson started to produce them in larger quantities that the revival really started. The revived instrument was a compromise between the the few (about a dozen) preserved bagpipes in Swedish museums, and the need for a bagpipe that goes well together with other instruments.

Bagpipe by Leif Eriksson

The latter need affected the choice of key and scale for the chanter - a choice that had to be made anyway, since nobody knew for sure how the old instruments were tuned. It also caused two deviations from the tradition. First, none of the preserved instruments had a tunable drone, while Eriksson equipped his drone with a tuning-slide. Second, after having made only a few instruments, Eriksson chose to turn the bag inside-out (the hair side of the hide inside the bag) to make it easier to make air-tight. Bagpipe by Leif Eriksson

The latter need affected the choice of key and scale for the chanter - a choice that had to be made anyway, since nobody knew for sure how the old instruments were tuned. It also caused two deviations from the tradition. First, none of the preserved instruments had a tunable drone, while Eriksson equipped his drone with a tuning-slide. Second, after having made only a few instruments, Eriksson chose to turn the bag inside-out (the hair side of the hide inside the bag) to make it easier to make air-tight.

Gudmundsons's LP

One of the first things to do after having revived the instrument, was to make it known. Per Gudmundson was, and still is, best known as a fiddler. That one of Sweden's greatest fiddlers sometimes put his fiddle away and played a tune or two on the Swedish bagpipes certainly helped spreading the news. Gudmundson also made an LP album, simply called "Säckpipa" (the Swedish word for bagpipe). A TV program about the revival was made, bagpipe courses and festivals were held regularly in Dalarna throughout the 80's, and other instrument makers started to make Swedish bagpipes - Alban Faust, Börs Anders Öhman and Bengt Sundberg being the most well known makers after Eriksson.

[1] The verb 'dråmba', meaning to play and hold a bass tone to a melody (on accordion) [2] Though not in the key nor the scale of Swedish bagpipes today. Gudmundsons's LP

One of the first things to do after having revived the instrument, was to make it known. Per Gudmundson was, and still is, best known as a fiddler. That one of Sweden's greatest fiddlers sometimes put his fiddle away and played a tune or two on the Swedish bagpipes certainly helped spreading the news. Gudmundson also made an LP album, simply called "Säckpipa" (the Swedish word for bagpipe). A TV program about the revival was made, bagpipe courses and festivals were held regularly in Dalarna throughout the 80's, and other instrument makers started to make Swedish bagpipes - Alban Faust, Börs Anders Öhman and Bengt Sundberg being the most well known makers after Eriksson.

[1] The verb 'dråmba', meaning to play and hold a bass tone to a melody (on accordion) [2] Though not in the key nor the scale of Swedish bagpipes today.

|

Instrument description

"Sweden's bagpipe usually only has a single drone, a sure sign of its great age and also an indication of good taste. For, how any melody could sound well, to the constant accompaniment not only of the keynote but also the low third, that is beyond our understanding."

C.A. Mankell 1853.

Bagpipe by Bengt Sundberg

Swedish bagpipes have their closest relatives in some East European bagpipes. They are mouth blown and have one free standing drone, across the piper's chest. Single reeds are used in both the drone and in the chanter, and both bores are cylindrical (6 mm). The pipes have a 'reedy' but reasonably quiet sound, comparable to a harmonica in tone and to a forcefully played violin in volume. Here is a sound example: Shepherds call from Lima (in Dalarna, not Peru!).

The basic Swedish bagpipe chanter has 6 finger holes and one hole for the top hand thumb. This is consistent with the preserved instruments from the past. The scale is an A-minor scale with the key note in the middle, ranging from e' to e''. Bagpipe by Bengt Sundberg

Swedish bagpipes have their closest relatives in some East European bagpipes. They are mouth blown and have one free standing drone, across the piper's chest. Single reeds are used in both the drone and in the chanter, and both bores are cylindrical (6 mm). The pipes have a 'reedy' but reasonably quiet sound, comparable to a harmonica in tone and to a forcefully played violin in volume. Here is a sound example: Shepherds call from Lima (in Dalarna, not Peru!).

The basic Swedish bagpipe chanter has 6 finger holes and one hole for the top hand thumb. This is consistent with the preserved instruments from the past. The scale is an A-minor scale with the key note in the middle, ranging from e' to e''.

(Click the image to hear the scale) (Click the image to hear the scale)

| A commercial retailer of Swedish bagpipes in the USA describes this scale as "the haunting Swedish scale". Indeed, in the key of E this scale would be unusual, also to a Swede, but the basic chanter is almost always played in A-minor. In that key the scale becomes less exotic, being the simplest possible minor scale - an A-major scale with a flat third.

The drone is most often tuned to e', retunable to d' by covering a tuning hole, but drones in a or e (an octave below the chanter's low e') are also common.

Reeds

The single reeds used in both the chanter and the drone are traditionally made from the only native reed useful for this purpose, Phragmites australis. However, Phragmites is very sensitive to humidity, so today it is common to use imported continental reed instead (Arundo donax) - the material used in most other reed instruments.

Single reeds are made by slicing a vibrating "tongue" from the straw, as in the picture. The reed to the left is made from Phragmites australis, the one to the right is made from Arundo donax. Note that the tongue can be cut both ways. See the section on Reed making for details.

The single reeds used in both the chanter and the drone are traditionally made from the only native reed useful for this purpose, Phragmites australis. However, Phragmites is very sensitive to humidity, so today it is common to use imported continental reed instead (Arundo donax) - the material used in most other reed instruments.

Single reeds are made by slicing a vibrating "tongue" from the straw, as in the picture. The reed to the left is made from Phragmites australis, the one to the right is made from Arundo donax. Note that the tongue can be cut both ways. See the section on Reed making for details.

|

Extensions

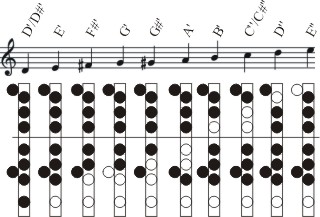

Today, one will also find Swedish bagpipes with more drones, bellows blown instruments, and chanters in D/G and C/F. Many modifications and extensions have been made to the basic scale. The most common extension is an extra finger hole just above the c'' hole, sounding c#''. The chanter can now be played in A-major.

A distinct feature of the Swedish bagpipe chanter comes in handy here - there is a deep depression for each finger, making it almost impossible to miss a finger hole. The c#'' hole is drilled in the same depression as the c'' hole, which makes it easy to cover both with one finger when playing in A-major. To play in A-minor the c#'' hole should be covered, e.g. with bees-wax or by a leather/rubber strap.

Chanters by Alban Faust

Another common extension is a hole for the right hand's little finger, making it possible to reach low d#' or d' (depending on the length of the chanter). Since the bore is cylindrical it is easy to extend the bore length, to obtain the more generally useful bottom note of d', for example by inserting a short piece of a drinking straw at the chanter end. It is also common to have a hole for the lower hand thumb, sounding g'.

The above extensions are more or less standard today, and yields the following scale. In the recording, I have tuned the chanter to A major, i.e. with both the c'' and the c#'' hole open. Both notes are played. The bottom note is d'. Chanters by Alban Faust

Another common extension is a hole for the right hand's little finger, making it possible to reach low d#' or d' (depending on the length of the chanter). Since the bore is cylindrical it is easy to extend the bore length, to obtain the more generally useful bottom note of d', for example by inserting a short piece of a drinking straw at the chanter end. It is also common to have a hole for the lower hand thumb, sounding g'.

The above extensions are more or less standard today, and yields the following scale. In the recording, I have tuned the chanter to A major, i.e. with both the c'' and the c#'' hole open. Both notes are played. The bottom note is d'.

(Click the image to hear the scale) (Click the image to hear the scale)

| It is now possible to play in the keys of A-minor, A-major, F#-minor, D-major, G-major and E-minor. Being able to play in D and G without having to swap chanters is particularly useful.

There are also chanters with an extra finger hole for the top hand index finger, just above the d'' hole (sounding d#''). This facilitates playing tunes in the key of E-major. Another extension, very rare on E/A-chanters but more common on D/G-chanters, is a small key at the top of the chanter, sounding f'' or f#'' when pressed (d#'' or e'' on a D/G-chanter). There are also playing techniques to extend the scale further.

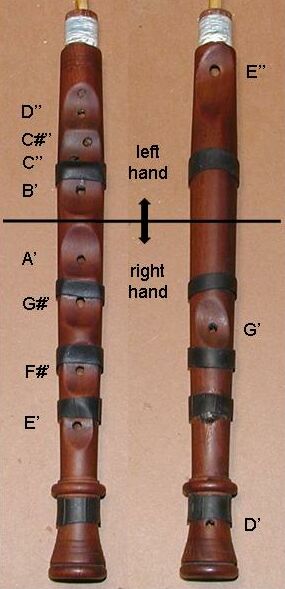

The picture to the right shows two chanters, one in E/A (left) and one in D/G (right). The D/G chanter has all the extensions mentioned above.

Bellows blown bagpipes

Bellows blown bagpipes are filled with air from bellows tied under the free arm. This is not a new invention - such bagpipes have existed for at least 500 years in central Europe - but Swedish bagpipes in particular have only been made this way since the 1980's and are still not very common.

Bellows blown bagpipe by Alban Faust

The main reason for having bellows is that it keeps the reeds dry, and thereby easier to keep in tune. Another advantage is that it makes it possible to sing while playing, as I do in this song from Småland (played on the bellows blown bagpipe depicted above). Bellows blown bagpipe by Alban Faust

The main reason for having bellows is that it keeps the reeds dry, and thereby easier to keep in tune. Another advantage is that it makes it possible to sing while playing, as I do in this song from Småland (played on the bellows blown bagpipe depicted above).

|

The music

Happy piper (the author)

"Only one for whom life no longer holds anything precious, can find it ridiculous when the Dalecarlian piper with his bagpipe produces the most vicious sounds, but yet looks so happy, turning his eyes to the heavens, as if in prayer. He is now dreaming of his life's happiest moments. The melodies taught to him as a young boy, takes the child of nature back again to the golden days of old. Eden, usually closed, opens up and the angel, who once had to close paradise, lowers his sword for ... the childlike mind."

C.A. Mankell 1853.

Not much is known about the tunes played by the bagpipers of old, nor how they played them. There is a (very short) list of tunes known to have been played by bagpipers, but all of them passed through other instruments on their way down to us.

Consequently, almost nothing is known about how, and to what extent, the old piper's ornamented their tunes. However, ornamentation in Swedish traditional music has never been that strict anyway - it is almost always improvised. So, the modern piper's ad hoc gracing may be exactly what the old pipers did as well.

There is no consensus on how a Swedish bagpipe chanter should be fingered, and most chanters are very forgiving to strange fingerings. Most experienced pipers play in a half-closed manner to facilitate a trick to simulate pauses and staccato notes; The six-finger note (e' on an E/A-chanter) is normally the same, and approximately as loud, as the drone note. So, momentarily closing all six finger holes gives a very convincing illusion of a pause. This can be heard in the music examples below.

You can read more about playing technique, including how to squeeze a few extra notes from your bagpipe, if you follow the link on how to play.

Bagpipe by Peter Frodemo

As for the music, the piper must go through the treasure of Swedish traditional music and search for the fraction of tunes that are playable using the cramped scale of the pipes. A lot is discarded, of course, or sometimes rewritten to fit the pipes, while some tunes fit in theory but never play well for other reasons. Some tunes, however, fit so well on the pipes that it is tempting to conclude that they were bagpipe tunes from the beginning. There is a certain thrill in finding such tunes.

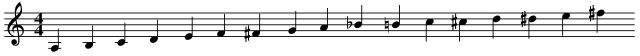

The adjoining music example is one of the most well known tunes among Swedish bagpipers. It is a polska - the most Swedish of all Swedish dances (but actually with Polish roots and closely related to the mazurka and polonaise). This particular polska is attributed to Nedergårds Lars - a legendary 19th century piper from Dalarna. Nedergårds Lars was a bear hunter (among other things), which explains his nick name, "Björskötten" (the bear shooter).

Click the music score to hear the tune (541k, 1:09, mp3)

Here is a video where I play the above tune:

and here is another video, where I play a wedding march, also after Nedergårds Lars:

Visit my YouTube channel for more videos.

Here are some other mp3 examples of traditional tunes, played by me on pipes made by Alban Faust:

- Enkronaspolskan ("the one crown polska", 700k, 1:30). This is a form of polska called "Bakmes" and is after Omas Ludvig Larson (GIF score)

- Polska efter Troskari Erik (453k, 0:58) is from Malung. (GIF score)

- Another polska efter Troskari Erik (501k, 1:04), played on two bagpipes.

- Gärdsbygubbarnas polska (628k, 1:02). This tune is from Dalsland and is played here together with my good friend Peter Frodemo on guitar. (GIF score)

- Brudmarsch från Dalby (486k, 0:48). This is a wedding march from Värmland. One wonders if the marriage was a happy one ... (GIF score)

- Springlek från Lima (990k, 2:10). Played on a bagpipe in D/G with two drones (GG). (GIF score)

- Säckpipslåt från Norra Råda (2520k, 2:45). A bagpipe tune from Värmland, played in D on two bagpipes in D/G. (GIF score)

- Ljugaren/The Miller of the Dee (3330k, 3:38) is a set of two tunes, played on two bagpipes in E/A. The first is a Swedish traditional tune, said to have been played by a woman after having seen her husband go through the ice and drown in lake Ljugaren. The Miller of the Dee is an English traditional tune with a long history and many common characteristics with Ljugaren. The two may very well have a common source. (GIF score of Ljugaren) (GIF score of The Miller ...)

- Polska efter Måns Olsson (1430k, 3:08). A tune from Jämtland, played on a bagpipe in D/G. (GIF score)

- Yet another polska efter Troskari Erik (977k, 2:05). One bagpipe in E/A. (GIF score)

- Polska efter Oppigårds Lars (597k, 1:16). Oppigårds Lars was a neighbouring fiddler to the above mentioned Nedergårds Lars. One bagpipe in E/A. (GIF score)

- Polska efter Carl Magnusson (959k, 2:02). A polska from Dalsland. Played in D on a bagpipe in D/G. (GIF score)

- Brudmarsch efter Bleckå efter Maklin (1314k, 2:47). A wedding march from Orsa in Dalarna, played on a bagpipe in E/A with a low E drone. (GIF score)

- Bröllopsmarsch efter Nedergårds Lars (927k, 1:58). A wedding march, played in F on bagpipes in D/G with a low C drone. (GIF score)

- Glad Sigfrid (1454k, 1:30), is a polska after Sigfrid Fridman, Norra Råda, Värmland. I learned it from Anders Norudde, who usually plays this tune with neutral thirds (pipes tuned halfway between major and minor). I play on pipes tuned in major, but I alternate between minor and major thirds. See the section on how to play for details. (JPG score)

Note that the version played is sometimes quite different from the corresponding music score. Swedish traditional music leaves plenty of room for free interpretation and there are very few 'rights' and 'wrongs'.

There are some more tunes under the section on Tunes for beginners, and also on my Facebook page.

Furthermore, I have collected and edited a set of 25 tunes after Petter Dufva (1756-1836). Petter Dufva was a fiddler but many of his tunes fit well on the bagpipes. The collection is commented in Swedish only, but the written music is of course language independent. Some of the tunes require the more advanced playing techniques described in the section on how to play. Here are four of these tunes, number 63, 101, 128 and 177, in a medley on Swedish bagpipes and hurdy-gurdy (with Göran Hallmarken):

A few recordings

There are only two albums with an explicit focus on Swedish bagpipes - the previously mentioned Säckpipa record (LP) by Per Gudmundson (1983), and my own Olle Gällmo - med pipan i säcken (2008). Gudmundson's LP is hard to find, unfortunately, and was never released on CD.

Anders Norudde's solo album "Kan själv!" (also sold under the English title "Himself") contains many very nice bagpipe tunes and is highly recommended.

The quartet Blå Bergens Borduner (The drones from the blue mountains) include three Swedish bagpipers. Their only record, by the same name as the group, include 8 tracks with Swedish bagpipes.

Another classic is the CD Bordunmusik från Dalsland (Drone music from Dalsland) with Alban Faust. Most tracks include bagpipes of Swedish, French, German or Flemish origin. 10 tracks include Swedish bagpipes.

Then there are a number of records where bagpipes are used, but more sparingly. Groups to look out for are, for example, Hedningarna, Lure (Valramn), Faust, Frifot, Dråm and Svanevit. Piper names to look for include Erik Ask-Upmark, Folke Dahlgren, Stefan Ekedahl, Alban Faust, Pär Furå, Per Gudmundson, Olle Gällmo, Per Jensen, Ulf Karlsson, Mikael Lund, Anders Norudde, Anton Olausson, Harald Pettersson, Anna Rynefors, Jan Winter and Jonas Åkerlund.

(Erik, Folke, Alban, Olle, Per J, Ulf, Mikael, Anders, Anton and Anna have received the honorary title "riksspelman" on Swedish bagpipe, which would roughly translate to "piper of the realm")

How to play

| I often get questions on playing technique - how to do this or that on a Swedish bagpipe. I have collected some tips and tricks on playing technique below. I assume (unless stated otherwise) that you have a Swedish bagpipe in E/A, i.e. with a chanter with the usual range between D' (or D#') and E''. There are three sections. The first, "Necessities" is for beginners, on how to play the pipes at all. Fancy playing techniques come further down, in sections "Gracings" and "Advanced". | |

| Necessities | |

| Holding the instrument The bag is usually tucked under the left arm, with the left hand above the right on the chanter. Some pipers hold the bag in front and press it towards the chest. The front of the chanter contains 6 or 7 depressions for the fingers. Older intruments may lack the bottom one - the one for the right hand little finger (pinkie) - but, if so, there is usually a hole there anyway, possibly on the side of the chanter (that is actually a tuning hole, but you should be able to reach it with your little finger). The second depression from the top usually contains two holes, on some chanters also the first. There are one or two depressions on the backside of the chanter. The three first depressions, counting from the top, are meant for your left hand index finger, long finger and ring finger, respectively. The next depression is for you right hand index finger, and so on. The left hand little finger is not used. The hole(s) on the backside is/are of course meant for you thumb(s). The picture to the right shows the front and back of a chanter in E/A. The black rings are rubber rings, cut from a bicycle tyre and used for fine tuning. The back side of this particular chanter has three holes. The one at the bottom is a tuning hole - it has no associated finger. The names beside the chanter tells which note is heard when the correspondin hole is open and all holes above it are closed. Traditionally, but also for technical reasons I will return to, bagpipes are usually played with straight fingers. Some pipers cover the finger holes with the middle part of the fingers, others with the end part (but, if so, still with the pad of the finger, not the tip). Personally, I do both. With my left hand, I cover the holes with the end part, while the right hand covers the holes with the middle part. The most important thing, though, is to be comfortable. To play well, you must be relaxed, which is hard enough anyway since the left upper arm is not. |  Front and back of a chanter in E/A. Front and back of a chanter in E/A.

The most interesting part of a piper's body. This is a chanter in D/G and the piece of metal on top is a key for top E (corresponding to F# on an E/A-chanter, but E/A-chanters do not normally have such a key). The print on the T-shirt is a 16th century drawing of a bear and a bagpiper, from Olaus Magnus' stories about the Nordic people. Photo: Mikael Larsson The most interesting part of a piper's body. This is a chanter in D/G and the piece of metal on top is a key for top E (corresponding to F# on an E/A-chanter, but E/A-chanters do not normally have such a key). The print on the T-shirt is a 16th century drawing of a bear and a bagpiper, from Olaus Magnus' stories about the Nordic people. Photo: Mikael Larsson

|

If you only blow air into the bag when you have to, you may find time to sing along while playing! (the instrumentet to the right is a hurdy-gurdy, played by Jan Winter) Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson If you only blow air into the bag when you have to, you may find time to sing along while playing! (the instrumentet to the right is a hurdy-gurdy, played by Jan Winter) Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson

| Blowing technique Beginners often blow into the bag constantly, until they have to take a quick breath. To do that is exhausting, and it may be difficult to maintain a steady tone. The air pressure, in the bag, should be essentially constant, and this pressure should be maintained with your arm, not with your lungs or diaphragm! Fill the bag only when you have to, i.e. typically not until you have squeezed out a lungfull from it with your arm. Do not keep the mouthpiece in your mouth, let it go when you don't need it. If you must fill the bag more often than every 5 seconds, something is wrong with your bag (it leaks) or your reeds (they require too much air). Release your arm pressure somewhat when you blow, to compensate for the incoming air. To learn how much to release pressure requires practice: Maintain a low note for a long time (several minutes) without fluctuations. Record this attempt on tape and then listen to yourself afterwards. It is a boring tune to listen to, I'm sure, but you may learn from it. |

| Fingering Compared to other instruments, the Swedish bagpipe is very forgiving when it comes to fingering. Most pipes keep in tune, no matter what you do with your fingers below the uppermost open hole. However, fingering does affect some of the playing techniques and tricks discussed later. A beginner typically plays with open fingering, which means that you lift all fingers from below and up to the sounding finger hole. If you play low E you have all your fingers, except your right little finger, on the chanter. When you play A you can wave to your mother in the audience with your right hand and when playing top E you can wave with the chanter, because nothing is holding it! (unless you keep one or two right hand fingers on the chanter just to hold it still) The opposite is closed fingering, where the starting point is bottom E, i.e. all fingers, except the right hand little finger, on the chanter. When playing another note, you lift the corresponding finger for that finger hole, but only that finger. (Of course, if you want to play low D/D# you close the finger hole under the right hand little finger instead.) Most experienced pipers use a fingering inbetween these two extremes, but more closed than open - halfclosed fingering. To keep as many fingers on the chanter as possible (n.b. except the right hand little finger) makes it easier to jump between two notes that are far apart, since fewer fingers need to move. A special case of that is staccato playing (see below). Closed fingering also affects sound a tiny bit (the sound becomes a little bit softer using closed fingeringen). But, depending on the size of the finger holes, some notes may play slightly out of tune if you play them completely closed. You should try this out on your own chanter. |  Look Ma! He is playing a closed D! Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson Look Ma! He is playing a closed D! Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson

An example of halfclosed fingering. Under each note is a schematic figure of the chanter, where a filled (black) circle denotes a closed finger hole and an unfilled (white) circle denotes an open finger hole. The two thumb holes are drawn outside the chanter. The horizontal line marks the border between the left (top) hand and the right (bottom) hand. An example of halfclosed fingering. Under each note is a schematic figure of the chanter, where a filled (black) circle denotes a closed finger hole and an unfilled (white) circle denotes an open finger hole. The two thumb holes are drawn outside the chanter. The horizontal line marks the border between the left (top) hand and the right (bottom) hand.

|

Bagpipers don't need lifejackets! (the guy to the right is Mikael Larsson, and we are on our way to a bagpipers' meeting in Estonia, summer 2004) Photo: Hans Rönnegård Bagpipers don't need lifejackets! (the guy to the right is Mikael Larsson, and we are on our way to a bagpipers' meeting in Estonia, summer 2004) Photo: Hans Rönnegård

| Note separation How do you separate the notes when the same note should be played twice in a row? This problem is probably unique to bagpipes. A pianist who wants to play the same note, X, several times, simply presses the X key several times. A flute player separates the notes with his/her tongue, forming a "T" or "K". The fiddler changes the direction of the bow stroke. In all three cases there is a short break between the notes. But the bagpipe is never silent (wouldn't your neighbours wish ...), so how is it done? Well, you will have to create the acoustic illusion of a break, by playing another note, Y, inbetween. In other words, you play XYX, but Y is played so short that it not heard as a note, it only separates the X's. There are two basic ways to to this, depending on whether Y is above or below X in the scale. A cut is when Y is above X. The note A, for example, can be cut in two by twitching any left hand finger (lift it and immediately lower it again). Since the note should be played so short that it isn't heard as a note, it should not matter which finger you twitch. However, it is not easy to do this well on Swedish bagpipes, since the notes above X are also stronger than X. So it is a good idea to choose which finger you twitch, so that, if the note is heard, it fits well with the melody. Sound example of a cut The other case is when Y is below X in the scale. This is called a tap because what you do is to quickly tap the finger hole for the sounding note with the corresponding finger. The middle note, Y, produced by doing this depends on the fingering - Y becomes the note of the uppermost open finger hole below X. In my opinion it is much easier to tap well than to cut well, i.e. to do it without the middle note, Y, being heard as a note. Sound example of a tap A third way to separate the X notes is to play the first one staccato. See the next tip. You might think of this as a special case of a tap but is not quite the same thing. |

| Short notes (staccato) You might argue that this does not belong to the "necessities" category, but in my opinion it does. In particular when playing for dancing, it is very important to produce a clear beat, and then it helps a lot if you can play with a bounce! If you want to play short notes, you should play with closed fingering (see the tip on fingering above). The trick is to play the note in question and then immediately go down to low E, which is then usually not heard as a note, but as a pause (especially if you have a drone which also sounds in E). If you play fully closed, you only have to move one finger to do this. If you play open, you must put several fingers down on the chanter at exactly the same time, which is difficult. Sound example Tip: This illusion does not work very well if the note you want to play staccato is close to the note you jump to (low E). Furthermore, no note works well staccato if the next note in the melody is low E, since when you get to that note in the melody, you are already there and must break it with a cut or a tap (see the section on note separation above). Sometimes I jump to some other note than low E, which may give the illusion that I play second voice with myself. Sound example: Springlek från Lima. If you plug the chanter end and any tuning holes you might have below the lowest finger hole, you can play true staccato's (really make the chanter silent) by closing all finger holes. But, if so, you also lose one note - low D/D# - since that is when the chanter is silenced. If you sit down when playing, you can refrain from plugging the chanter and, thereby, keep the possibility to play D/D#. When you want the chanter to stop, you play D/D# but at the same time lower the chanter end to your leg, temporarily plugging it. (You may recognize this technique if you have seen an Irish Uilleann piper in action) |  Two Norwegian halling dancers in Ransäter 2003. These guys really depend on the music being played with a clear beat! Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson Two Norwegian halling dancers in Ransäter 2003. These guys really depend on the music being played with a clear beat! Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson

|

| Gracings and other decorative frills | |

Mikael Larsson in deep concentration (Pipers' meeting in Gagnef 2002) Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson Mikael Larsson in deep concentration (Pipers' meeting in Gagnef 2002) Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson

| Grace notes A grace note is a short note, played just before the melody note it is supposed to decorate. On bagpipes, melody notes are usually graced from above, i.e. the grace note is above the melody note in the scale. This makes it equivalent to a cut, as discussed before in the section on note separation. The only difference is that, here, it is just a decoration, not a necessity. This also implies that, this time, we want the extra note to be heard. I usually try to choose my grace notes so that they fit the melody, i.e. notes that would have made a good harmony to the melody. Sound example 1 Grace notes can also be an effective way to mark the beat, in particular if combined with a staccato of the melody note you end up on. Sound example 2 If you want, you can take this to the extreme, playing several grace notes in sequence to form arpeggio's (broken chords): Sound example 3 |

| How to vibrate notes (vibrato) The most common (and most simple) way to play vibrato is to repeatedly open and close one or several finger holes below the sounding hole. The fingers flutter. The effect depends on the size of the finger hole of the sounding note. A small finger hole gives a greater vibrato effect than a large one. Sound example Which finger(s) to flutter depends on the note and the chanter. You'll simply have to try it out. I vibrate all notes above A with the same finger - my right hand index finger. Sometimes, I vibrate the left hand thumb hole, top E, with the left hand index finger. The lower notes, I vibrate with the finger immediately below the sounding hole. Of course, the very lowest notes, E and D/D#, can not be vibrated this way. If you where to flutter the finger for the sounding note, instead of a finger below that, the note would change to some other (lower) note. It would produce a trill, rather than a vibrato. But, if you hit the finger hole on an angle, on purpose missing part of the finger hole, you can get a vibrato effect. The problem is to hit it exactly right every time. If you cover too little of the hole, there is no effect and if you cover too much of it you produce a trill instead of a vibrato. This is much more difficult than to flutter the fingers below the sounding hole, as described above. Other variants include shaking the chanter (up and down or to the sides) and to squeeze the neck of the bag with the right hand (if it is free). The latter sounds quite funny - like a waw-waw effect. |  Stefan Ekedahl in action (Pipers' meeting in Gagnef 2002) Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson Stefan Ekedahl in action (Pipers' meeting in Gagnef 2002) Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson

|

Jam session in Ransäter, 2003 Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson Jam session in Ransäter, 2003 Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson

| How to slide up to a note (glissando) Instead of lifting the finger the usual way, uncover the finger hole gradually. If you play with straight fingers you can bend them off the hole. Some piper roll the fingers off (upwards). If you play with the end part of the finger, you can pull it to the side, towards the hand. I usually bend. Sound example |

| More advanced techniques (to extend the scale, etc) Note! The tricks below may not work on all bagpipes! | |

| Volume control when playing with others One limitation of bagpipes is that it is difficult to adjust sound volume. In particular when playing together with other instrument, or if someone is supposed to sing along, this can be a major problem. If you have several reeds to select from, choose the right one for the right occasion. Different reeds can differ much in sound volume. You can adjust sound volume somewhat by varying you arm pressure on the bag. Unfortunately, the notes often vary more in pitch than they do in volume (in particular notes close both ends of the chanter's range). Fingering actually has some effect (though small) on volume. Closed fingering is more silent than open. At least to a person in front of you (e.g. your audience). When you play closed, much of the sound is directed down, towards the floor. When you play open, much of it is directed towards your audience, through the finger holes. This is also why top E, the thumb hole note, sounds so much stronger than the others to the piper. (It is stronger than the others, but not by as much as the piper might think). If you play together with a weaker instrument which is to take over the melody, pull the lower half the chanter towards you and bend forward slightly. The combination of a slight decrease of bag pressure and the chanter suddenly being positioned in parallel to the floor (i.e. with the finger holes directed down), may actually help a lot. If you also take a step or two backwards, this can be quite effective. (The audience might think that you are bowing to them, but that's not a problem, is it?) The upper half of the scale is stronger than the lower half. If someone else is taking over the melody, and you are to play a second voice, keep in the lower half of the scale. Maybe you don't have to play the second voice either - you may want to stay put on low E, as a drone, for a while. |  The Celsius trio in Viksta church, August 2002. Me, Elisabet Börjesson and Gunnar Börjesson. Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson The Celsius trio in Viksta church, August 2002. Me, Elisabet Börjesson and Gunnar Börjesson. Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson

|

Your's truly, playing a tune at Byss-Callestämman in Uppland, 2004. Even a small extension to the Swedish bagpipe scale is helpful when playing tunes from Uppland (most of them are intended for Nyckelharpa, which has a much wider range than the bagpipe) Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson Your's truly, playing a tune at Byss-Callestämman in Uppland, 2004. Even a small extension to the Swedish bagpipe scale is helpful when playing tunes from Uppland (most of them are intended for Nyckelharpa, which has a much wider range than the bagpipe) Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson

| Top D# Some chanters have two finger holes under the left hand index finger, of which the upper one (D#) is usually covered by bees-wax or similar. This is the same principle as the double hole one step below (used to switch between major and minor). But you can acually play D# without that extra finger hole. If you come from above, i.e. from top E, it is not that difficult. Lift your left index finger as if to play D, but do not cover the thumb hole in the usual way. Instead, bend you thumb and force your thumb nail into the hole. In theory you should not have to lift the D-finger (the index finger) at all, but in my experience it is easier to find a true D# that way. Besides, if you cover the D-hole, your chanter may start screaming instead (an effect which will be exploited later). Sound example When I go directly to D# from below, I bend my thumb in place - I never lift it from the hole. But it is sometimes easier to just slide the thumb down, to uncover the upper half of the hole, without using the nail. |

| Top F Play top E, i.e. lift your left thumb, and then gradually increase pressure on the bag with your arm. The note goes sharp, doesn't it? If the reed is too stable, nothing much happens. If it is too weak, it may stop (from sounding, completely). But if your reed is just right, you can reach F this way, or even higher. With a really good reed (and some practice) you can go directly up to F, without sliding up, by increasing the pressure by the right amount at exactly the right moment. Sound example Music example: Brudmarsch från Dalby |  We both play with a bow! Magnus Holmström and me in Österbybruk, 2003. Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson We both play with a bow! Magnus Holmström and me in Österbybruk, 2003. Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson

|

Now, doesn't this look nice? (Ransäter 2004) Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson Now, doesn't this look nice? (Ransäter 2004) Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson

| Bottom C# This only works on chanters with a tuning hole below the hole under your right hand little finger. I assume that the note you get, when covering the hole with your right hand little finger, is a D (on some chanters it is a D#). If so, and with some luck, you can go down even furter, to C#, by pressing the chanter end to your leg. You probably want to sit down when you do this. The only open hole, when you do this, is the tuning hole. In the following sound examples, I play on a chanter in D/G, so the low note is actually a B, but it is produced in the same way. Sound example 1 (The lowest note sounds more closed in than the others. It is, after all ...) Sound example 2 (The end note of the lower voice) Music example: Bröllopsmarsch efter Nedergårds Lars (Sound example 1 above was cut from this tune, which also happens to be an example of a tune being played in the "wrong" key - see below) This is not easy - the chanter may stop, or scream. Even if it does work, the note produced may not be quite in tune. In the second example above, you can hear that it takes some time for the note to converge (I compensate with the arm pressure on the bag). If you need to flatten the note you get, you can put some bees-wax on the lower edge of the tuning hole. (in the lower edge, to minimize the effect on the D note, which is tuned using the same tuning hole). |

| Switching between major and minor while playing Usually, the piper tunes the chanter to major or minor before starting to play. This is done by uncovering, or covering, the upper of the two finger holes under the left hand long finger (with bees-wax for example). In other words, on an E/A-chanter you select in beforehand if you want the left hand long finger to control the note C# (when in major) or C (when in minor). If both C and C# are required in the same tune, you should tune to major, i.e. uncover the C# hole. C# is then played as ususal, by lifting the finger. When playing C, you start bending it off instead, as if you wanted to slide up to C# (see the question on glissando). This you do until only the C-hole is open, then you stop. This requires that the C# hole is closer to the left hand side of the chanter than the C hole, which is usually the case. Some pipers prefer to roll the finger upwards instead. This has the advantage that it works also if the C# hole is on the wrong side. Pipers who cover the finger holes with the end part of the finger can pull the finger to the side, towards the hand, instead of bending or rolling, given that the C# hole is on the left hand side. Sound example Music example: Glad Sigfrid |  Another jam session in Ransäter, 2003 Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson Another jam session in Ransäter, 2003 Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson

|

Rino Rotevatn and Mikael Lund (Pipers' meeting in Gagnef 2002) Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson Rino Rotevatn and Mikael Lund (Pipers' meeting in Gagnef 2002) Photo: Anne-Marie Eriksson

| Playing in G or D major on an E/A-chanter

This requires two things from your chanter.

|

| Top E, and beyond, on D/G-chanters without an E-key Some chanters in D/G have a key above the left hand index finger, sounding E when pressed. (The corresponding key on an E/A-chanter would be an F#-key, but is very rare.) The hole uncovered by the key is very close to the reed and the tone is therefore stronger and more raw than any other on the chanter - you probably don't want to stay there for long. However, on many D/G-chanters (depending on the reed) you can take this note in another way, with nicer sound and without using the key! Play top D (lift your left thumb) with all other fingers, including the right hand thumb and little finger, on the chanter. Now go directly down to low C, i.e. cover the E-hole with your thumb, but at the same time lower the arm pressure on the bag (a lot). It is very probable that this causes the chanter to shreek instead of sounding low C. That "shreek" is actually a note - on all chanters I have tried this on, it is an E, i.e. the same note that would be reached by pressing the key (if you have one), but the sound is much nicer. Softer, like a falsetto. Unfortunately, it is difficult to time the pressure drop so that the chanter produces an E at exactly the right moment in the melody you play, so it is usually better to take this note another way: Play top D again, as above with all other fingers on the chanter. Now, instead of covering the thumb hole the usual way, bend your thumb and force your thumb nail into the hole. You then cover only part of the hole (recorder players probably recognize this technique). With some practice, you'll learn just how much of the hole to cover to produce the same note as above, top E. The advantage is that you do not have to decrease your arm pressure on the bag as much, and this makes it easier to time right. On some chanters you can then lift you right hand little finger and reach even higher than E. In this Sound example I first play top E using the key I have on my chanter. The second time I reach E by lowering the pressure as above. The third time I use the trick with the thumb nail instead. Finally, the fourth time I go up to F# by also lifting my right hand little finger. Unfortunately, this trick very seldom works on E/A-chanters - I don't know why. This is particularly unfortunate, since E/A-chanters usually do not have a key for the extra note either. But, so far, it has worked on every D/G-chanter I have tried (including Estonian Torupills in the same key). It seems to be more reliable on bellows blown bagpipes than on mouth blown ones. Tip: Don't practice this when your neighbours are in! |  15th century bagpiper in Härkeberga kyrka in Uppland. 15th century bagpiper in Härkeberga kyrka in Uppland.

|

| Conclusion: More than an octave and a half! | |

Just to show (off) that all these tricks are doable on the same chanter, I include here a sound example where I play all the extra notes mentioned above. This, I do on my chanter in D/G. It is difficult to play these notes in any order, but they are all there. The range is now an octave and a fifth! Yet, I have excluded a note which I can play sometimes, but only sometimes (which is why I have not described it here) - a rough low A on the D/G chanter (H on a E/A chanter). Including that, my chanter has a range of an octave and sixth:

The range of my D/G chanter

Even if you, your chanter and/or your reed won't play along with all these tricks, I'm sure that you can squeeze some extra notes from it. Enjoy! The range of my D/G chanter

Even if you, your chanter and/or your reed won't play along with all these tricks, I'm sure that you can squeeze some extra notes from it. Enjoy!

|

Date: 2016-01-03; view: 1806

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| THE SUPPOSITIONAL MOOD | | | Some beginner friendly tunes |