CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

The Psychology of War

Why do human beings find it so difficult to live in peace?

Published on March 5, 2014 by Steve Taylor, Ph.D. in Out of the Darkness

Read any book about the history of the World and it’s likely that you’ll be left with one overriding impression: that human beings find it impossible to live in peace with one another. And just when the world appears to be close to another major conflict—the stand off between Russia and Ukraine which has been developing over the last few days—it seems a good time to ponder over why this seems to be the case.

Books on world history usually begin with the civilizations of Sumer and Egypt, which arose at around 3000 BC, and from that point until the present day, history is little more than a catalogue of endless wars. Between 1740 and 1897, there were 230 wars and revolutions in Europe, and during this time countries were almost bankrupting themselves with their military expenditure. Warfare actually became slightly less frequent during the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries, but this was only because of the awesome technological power which nations could now utilize, which meant that wars were over more quickly. In actual fact, the death toll from wars rose sharply. Whereas only 30 million people died in all the wars between 1740 and 1897, estimates of the number of dead in the First World War range from 5 million to 13 million, and a staggering 50 million people died during the Second World War. (Since then, deaths from warfare have declined significantly, for reasons which I will discuss later.)

Theories of Warfare

So how can we explain this pathological behavior?

Evolutionary psychologists sometimes suggest that it’s natural for human groups to wage war because we’re made up of selfish genes which demand to be replicated. So it’s natural for us to try to get hold of resources which help us to survive, and to fight over them with other groups. Other groups potentially endanger our survival, and so we have to compete and fight with them. There are also biological attempts to explain war. Men are biologically primed to fight wars because of the large amount of testosterone they contain, since it is widely believed that testosterone is linked to aggression. Violence may also be linked to a low level of serotonin, since there is evidence that when animals are injected with serotonin they become less aggressive.

However, these explanations are highly problematic. For example, they cannot explain the apparent lack of warfare in early human history, or pre-history, and the relative lack of conflict in most traditional hunter-gatherer societies. This is a hotly debated issue, and there are some scholars and scientists who claim that warfare has always existed in human societies. However, many archaeologists and anthropologists dispute this, and I believe that the evidence is firmly on their side. For example, last year the anthropologists Douglas Fry and Patrik Soderberg published a study of violence in 21 modern day hunter-gatherer groups, and found that, over the last two hundred years, lethal attacks by one group on another were extremely rare. They identified 148 deaths by violence amongst the groups during this period, and found that the great majority were the result of one-on-one conflict, or family feuds. Similarly, the anthropologist R. Brian Ferguson has amassed convincing evidence to show that warfare is only around 10,000 years old, and only became frequent from around 6000 years ago.

And one problem biological theories of warfare is that, while they might be able to explain specific outbreaks of violence, warfare is actually much more than this. Warfare is a highly planned and highly organized activity, mostly conducted and organized in non-violent situations - which does not involve a great deal of actual fighting.*

Psychological Explanations

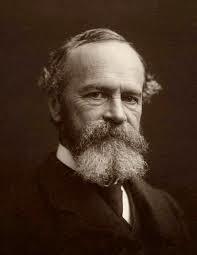

William James

The first psychologist to investigate war was William James, who wrote the seminal essay ‘The Moral Equivalent of War’ in 1910. Here James suggested that warfare was so prevalent because of its positive psychological effects, both on the individual and on society as whole. On a social level, war beings a sense of unity, in the face of a collective threat. It binds people together—not just the army engaged in battle, but the whole community. It brings what James referred to as ‘discipline’—a sense of cohesion, with communal goals. The ‘war effort’ inspires individual citizens (not just soldiers) to behave honorably and unselfishly, in the service of a greater good.

On an individual level, one of the positive effects of war is that it makes people feel more alive, more alert and awake. In James’ words, it ‘redeem[s] life from flat degeneration.’ It supplies meaning and purpose, transcending the monotony of everyday life. As James puts it, ‘Life seems cast upon a higher plane of power.’ Warfare also enables the expression of higher human qualities which often lie dormant in ordinary life, such asdiscipline, courage, unselfishness and self-sacrifice.

In my book Back to Sanity, I emphasize two further important factors. One obvious factor the drive to increase wealth, status and power. A major motivation of warfare is the desire of one group of human beings—usually governments, but often the general population of a country, tribe or ethnic group—to increase their power and wealth. The group tries to do this by conquering and subjugating other groups, and by seizing their territory and resources. Pick almost any war in history and you’ll find some variant of these causes: wars to annex new territory, to colonize new lands, to take control of valuable minerals or oil, to help build an empire to increase prestige and wealth, or to avenge a previous humiliation, which diminished a group’s power, prestige, and wealth. The present conflict in the Ukraine can be partly interpreted in these terms—the result of Russia’s desire to increase its territory and prestige by gaining control of the Crimea, and responding to the prestige-weakening blow of losing its favoredgovernment in the Ukraine.

Secondly, war is strongly related to group identity. Human beings in general have a strong need for belonging and identity which can easily manifest itself in ethnicism, nationalism, or religious dogmatism. It encourages us to cling to the identity of our ethnic group, country or religion, and to feel a sense of pride in being ‘British,’ ‘American,’ ‘White,’ ‘Black,’ ‘Christian,’ ‘Muslim,’ or ‘Protestant’ or ‘Catholic.’

The problem with this isn’t so much having pride in our identity, but the attitude it engenders towards other groups. Identifying exclusively with a particular group automatically creates a sense of rivalry and enmity with other groups. It creates an ‘in–out group’ mentality, which can easily lead to conflict. In fact, most conflicts throughout history have been a clash between two or more different ‘identity groups’—the Christians and Muslims in the Crusades, the Jews and Arabs, Hindus and Muslims in India, the Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland, the Israelis and Palestinians, the Serbs, Croats, and Bosnians, and so on. Again, the present conflict in Ukraine is easily interpreted in these terms. The dispute over Crimea lies in the fact that most of the region’s population identify themselves as ethnically Russian, while the ethnic Ukrainians wish to preserve their own independent identity, away from Russian influence.

The issue of empathy is important here too. One of the most dangerous aspects of group identity is what psychologists call ‘moral exclusion.’ This happens when we withdraw moral and human rights to other groups, and deny them respect and justice. Moral standards are only applied to members of our own group. We exclude members of other groups from our ‘moral community,’ and it becomes all too easy for us to exploit, oppress, and even kill them.

Date: 2015-01-02; view: 3498

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| The late Ockie at Rockhampton Zoo | | | The Decline of Warfare |