CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

The Nature and Analysis of Faults

Contents

Preface

Using this Book

Speech as a Habit

The Nature and Analysis of Faults

Analysis of faults • Correction of problems •

Attitude to correction • Principles of correction

Relaxation

Some common causes of tension • Exercises

Posture

Common faults • Recommended standing position

Exercises to improve general posture

PROBLEMS OF VOICE PRODUCTION Faulty Breathing

Recommended methods • Main faults • Popular misconceptions about breathing • Exercises for breathing ■ To establish the movement of ribs and diaphragm • Exercises for capacity and control • Exercises for power • Practice material for breathing and phrasing

Inadequate Pitch Range in the Voice

Main faults ■ Correction • Exercises • Practice pieces

Faulty Tone

Correction • Balanced use of the resonators • Exercises

Routines for Establishment of Forward Placing of the Voice

SPEECH FAULTS

Introductory

The English R Sound

Main faults • Correction • Exercises • Forming R Words to practise R ■ Sentences to practise R

The S Sound

Main faults ■ Correction • Forming S • Words to practise S ■ Sentences to practise S

Clear and Dark L

Main faults • Correction • Exercises ■ Practice words ■ Sentences

The TH Sound

Main faults • Correction • Forming TH ■ Practice words ■ Sentences

The Glottal Stop

Main faults • Correction • Exercises

Indistinct Speech

Exercises for the lips ■ Exercises for the tongue • Exercises for the soft palate and back of the tongue • Consonant exercises • Exercises for general agility of the organs of speech

Note to Teachers

Preface

Being mindful of the title and intent of this book, I have considerably revised and enhanced the chapter on Indistinct Speech. I have attempted to provide an improved explanation for this 'catch-all' term. In addition I have included exercises for the articulation of final consonants and some more exercises for the general agility of the organs of speech. I am genuinely pleased that this book has had such an enduring impact and hope that this new edition with its improvements may prove to be equally helpful.

Using this Book

'I do not much dislike the matter, but the manner of his speech.'

Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra

How many people, in all walks of life, have had their career, even their personal relationships, marred by some little quirk of voice or speech that reduces their ability to communicate fully what they want to express? Yet it is surprising how easily and effectively such habits can be changed, given the necessary information.

There are thousands of people who need this kind of help: they may be dissatisfied with the quality of their voice, or they may feel that there are certain intrusive elements in their speech which are so distinctive as to draw attention to their mode of delivery rather than what they are trying to say. These are usually faults which can be corrected.

This is not to say that our voice or our manner of speech is not a highly personal expression of personality - it is. For that reason, this book makes no attempt to pass judgement on distinctions of dialect, nor to lay down some artificial definition of 'correct speech'. It leaves the reader free to make his or her individual decisions on the voice that he or she wants. Having made those decisions the techniques described here may be used to take the appropriate corrective action.

For example, the actor who has an unusual 'R' sound will very probably feel that that particular sound is not adequate to meet the needs of the variety of characters he or she must represent. So a change is made and the most common formation of the sound is acquired - he or she can also learn how to produce faulty formations if they best represent the character to be played. Likewise the public speaker who finds that the voice lacks strength or the authority to make the point may make a choice to

develop the required characteristics in his or her voice. In each of these cases, changes are being made in habits of voice or speech which may have been found perfectly satisfactory in ordinary conversation but are obviously unsatisfactory for specific situations.

The study of voice and speech can be complex. It is a subject beset by attitudes ranging from fear to bewilderment at its mystique. The aim of this book is to remove some of the fears and to unravel the mystique. Truly scientific study of the nature of voice and speech is a recent development, since only recently have we had the technology to provide sophisticated machinery which can measure with any exactitude the activities involved in producing speech. Over a very short period of time a large amount of knowledge has been accumulated on the formation of speech, and in these pages I have tried to present some of that knowledge, as simply and directly as possible. I have not attempted to produce an exhaustive textbook on phonetics, nor a study of those complex, often physiological problems of speech which are more appropriately dealt with by a qualified speech therapist. What I have covered are the problems I have most commonly met in a long period of professional voice teaching, with particular attention to those which respond to well-directed self-help.

In the sections that follow, therefore, you will first find the facts necessary to understand a particular problem -what is its cause, what is the correct formation - followed by tested, practical exercises to help bring about the correction required.

I have deliberately avoided the use of complex and unfamiliar technical terms, to keep the book readable and to enable even the inexperienced reader to follow its descriptions. This does not mean that the book renders a teacher superfluous. The teacher who reads this book will find a wealth of corrective exercises on which to draw, and be aware of the simplifications of terminology and analysis which have been made in order to stress the practical element in retraining the habit. Wherever possible, the nonexpert should consult a teacher on the best use of this book and its exercise material. If, however, such help is not available, you should find that you can achieve a great deal for yourself by patient and careful application to the principles and exercises given here.

None of the faults analysed here is attributable to a physical or structural fault in the speech-mechanism - these must be the concern of trained professionals. We are concerned with the misunderstanding or mismanagement of an otherwise healthy instrument. The whole emphasis is on the readjustment of habits - a readjustment anyone can make through thorough, frequent, and informed practice of the material in these pages.

Speech as a Habit

Speech and the use of voice are habits which are built up and consolidated during the lifetime of an individual. From an early age one experiences the necessity and value of making verbal communication with another individual, and through a gradual process of imitation and selection the habit is formed. Just as a baby recognises that to point at something denotes interest in the object so he or she learns that to identify it verbally has the same effect. This involves the child in a serious study of recognition; first, of other people's capacity to verbalise, and then his or her own physical ability to form all the constituent sounds which accumulate into a message. In attempting to correspond with the verbal habits of the environment a child gradually begins to gain control over his or her voice and speech and to learn its value in bringing satisfaction to the appetites, whether physical or emotional.

Naturally, in developing the habit of voice and speech, only those features which ensure maximum effectiveness within the environment are acquired. For example where the intellectual demands are very small in the first years of life a child will require little subtlety of intonation or definition of sounds. As the demands for precision in thought and articulation are increased, so the habit of speech is modified and extended accordingly.

Since the habit of speech is acquired in specific response to the environment he or she will gradually build a habit to operate most effectively within that limited area. It may well be, and often is the case, that as a person grows older and his or her horizons, geographical, social and emotional, are extended he or she will find that certain early habit-patterns are of limited, or no, use.

The Nature and Analysis of Faults

Voice and speech problems divide themselves, simply, into three basic categories:

1. Those caused by some structural deficiency in the mechanism, for example cleft palate speech or hare lip.

2. Emotional and psychological problems.

3. Adequate mechanism but basic mismanagement of it.

It is not the scope of this book to deal with 1 and 2. These require the skills of Speech Therapists and suitably qualified medical practitioners.

In order to establish what a 'fault' in voice and speech is it is necessary to establish a Norm by which all other assumptions as to speech adequacy are relative.

These 'norms' are not universal and the discretion of the speaker or teacher has to be sensitively exercised to determine the relative acceptability of a problem. For instance the uvular R heard in French and German is not a usual element of English speech. As a result the use of such an R in English, although not inhibiting the understanding of the message conveyed by the speaker, would normally draw attention to itself and the way that the speaker is communicating. It is this element of conspicuous diction with which this book is concerned.

Normal, or rather adequate, speech is that form of verbal communication which may be anticipated in any given environment. It draws the least attention to the way in which a speaker communicates while expressing the message of the speaker with maximum control over his environment; and the realisation of all his objectives in terms of response from his audience.

It is easy to see the application of the foregoing statements in relation to speech, where the chances of a child speaking with a defective form of R sound are greater if the whole of his or her immediate family use the same kind of sound, but these principles apply equally to the production of voice. Examples are the family which permanently uses a high pitched voice, or the worker who develops an habitual loud volume as a result of competing with noisy machinery in his or her job.

Given that voice and speech are developed by habit it follows that, in order to effect a correction or modification, it is necessary to build up a new habit.

ANALYSISOF FAULTS

In order to establish a clear understanding of the problems of a speaker it is necessary to approach the problem analytically. In general, given that the speaker possesses a healthy vocal instrument with no organic defect, the problems divide themselves into the following categories:

1. Problems of voice production. These are concerned with the basic sound which the speaker produces. Voice is the means by which we recognise the identity of a speaker.

2. Problems of articulation. These are the difficulties experienced in making specific speech sounds, individually and in combination, in any given language. Speech may be defined as the pattern of sound which we create by movements of the tongue, lips and soft palate.

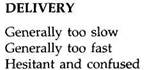

3. Problems of delivery. Once the voice is adequately produced and the speech pattern is acceptable it is still possible that the delivery does not efficiently communicate the attitude of the speaker to the listener or to the subject matter. For example: the voice and speech may be technically exact, but the rate of delivery is too fast either for the listener to assimilate or for the speaker to express adequately the feeling implied.

The following list may provide a reasonable means of assessing the adequacy of voice and speech:

VOICE PRODUCTION

Date: 2015-12-24; view: 900

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Lži o Katyni odhaleny | | | PRINCIPLES OF CORRECTION |