CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Chapter 3. The Happy Planet Index

The Happy Planet Index (HPI) is a new measure of progress. It tells us how well nations are doing in terms of supporting their inhabitants to live good lives now, while ensuring that others can do the same in the future. It points the way towards sustainable well-being for all.

The HPI provides a single, easily communicable headline indicator which gives an overall sense of whether a society is heading in the right direction.

Of course, human society is complicated. There are so many things that matter to us, so many things going on, that measuring everything would be impossible. The Earth and the health of its ecosystems are no simpler. What can we measure that will allow us to decide whether our societies are improving or not? What can we model to judge whether a particular course of action is likely to be for the better or the worse?

Overall indicator needs to take two things into account – current well-being and our impact on the planet. The following paragraphs explain how the HPI measures these factors through three components: experienced well-being, life expectancy, and Ecological Footprint; and how it brings them together into a single meaningful efficiency measure, to produce one of the first global measures of sustainable well-being.

Well-being

If you want to know how well someone’s life is going, your best bet is to ask them. The HPI uses data from surveys which do just that, providing a measure of experienced well-being.

When asking people how they themselves feel about their lives, researchers allow them to decide what is important to them, to assess the issues according to their own criteria, to weight each one as they choose, and to produce an overall response. This democratic, non-paternalistic approach does not rely on experts knowing what is ‘best’ for people. It also measures something which is universally considered valuable – everybody wants to feel good about their life. This applies across cultures and also across time.

Another approach that could be adopted would be to create a list of things which researchers think are important to people’s well-being – for example, education, income, and safety – measure them, and then bring them together into some kind of index. But how do researchers decide what things to include in that list and how do they combine them? Should some things be given more weighting than others? And what does the number that comes out at the end actually mean?

Measuring well-being through direct measures of experience using survey data, builds on a rich vein of psychology, economics, and sociology research. In this report, experienced well-being is assessed using a question called the ‘Ladder of Life’ from the Gallup World Poll. This asks respondents to imagine a ladder, where 0 represents the worst possible life and 10 the best possible life, and report the step of the ladder they are currently standing on.

Life expectancy

Alongside experienced well-being, researchers also include a measure of health – life expectancy. They use this measure because health is also universally considered important. For example, the OECD has recently collected data from its Better Life Index website which allows it to compare how people rate the importance of a range of different life domains. The two highest ratings are given to life satisfaction (a measure of experienced well-being), and health. Furthermore, these two domains remain the top two factors in eight out of eleven world regions. Average life expectancy is a well-established indicator that has been calculated since the nineteenth century. In fledgling Germany, Bismarck based the state retirement age of 65 on life expectancy data. The UN’s Human Development Index has included life expectancy since its inception.

Researchers have combined life expectancy and experienced well-being in a variation of an indicator called Happy Life Years, developed by sociologist Ruut Veenhoven. Modelled on the indicator Quality Adjusted Life Years, this indicator is calculated by adjusting life expectancy in a country by average levels of experienced well-being.

Environmental impact

Unless you care nothing for the future – neither your own, nor that of your children, nor that of future generations – environmental impact matters. We live in a world of scarce resources.

A society that achieves high well-being now, but consumes so much that sufficient resources are not available for future generations, can hardly be considered successful. Nor could one that depends on the extraction of resources from other countries, leaving their inhabitants with nothing. For that reason, resource consumption is central to the HPI.

Researchers use the Ecological Footprint, a metric of human demand on nature, used widely by NGOs, the UN, and several national governments. It measures the amount of land required to sustain a country’s consumption patterns. It includes the land required to provide the renewable resources people use (most importantly food and wood products), the area occupied by infrastructure, and the area required to absorb CO2 emissions. Crucially it includes ‘embedded’ land and emissions from imports. So the CO2 associated with the manufacture of a mobile phone made in China, but then bought by someone living in Chile, will count towards Chile’s Ecological Footprint, not China’s.

Calculating the index

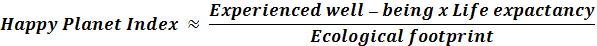

Achieving the two elements of sustainable well-being requires efficiency. The HPI measures this as the number of Happy Life Years achieved per unit of resource use. This is calculated approximately by dividing Happy Life Years by Ecological Footprint. (‘Approximately’ because there are some adjustments to ensure that all three components – experienced well-being, life expectancy and Ecological Footprint – have equal variance so that no single component dominates the overall Index).

Date: 2014-12-21; view: 1695

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Chapter 2. Measuring happiness | | | Chapter 4. results: an amber planet |