CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Mikhail Vrubel

In 1890 V. Serov introduced his close friend Mikhail Vrubel (1856—1910) to Mamontov. It was to prove the turning-point of Vrubel's artistic life. He had had a brilliant early career at the Petersburg Academy, which he entered in 1880. Even before he graduated, Vrubel's teachers recommended him to Prolessor Prakhov who came to the school in 1883 to find students who would help him with the restoration of the twelfth-century church of Saint Cyril in Kiev. The opportunity to become familiar with Byzantine art at first hand proved decisive in Vrubel's development. At this point began that relentless search for a new pictorial vocabulary which was the driving force throughout his work. It was during Vrubel's work in Saint Cyril that he discovered the eloquence of line. "Byzantine painting", wrote Vru-bel later, "differs fundamentally from three-dimensional art. Its whole essence lies in the ornamental arrangement of form which emphasises the flatness of the wall." This use of ornamental rhythms to point up the flat surface of the canvas was constantly exploited by Vrubel. An example of this is "The Dance of Tamara", a water-colour of 1890. This is one of the series by Vrubel illustrating Lermontov's poem "The Demon", commissioned for a jubilee edition published in 1890. It was Vrubel's first Moscow commission.

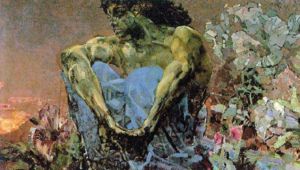

The passionate study of Byzantine art which Kiev inspired in Vrubel took him next to Venice. In Kiev he had discovered line, in Venice he discovered colour. When Vrubel returned to Russia in 1885 he began the series of "Demon" pictures inspired by Lermontov. This image came to haunt him more and more persistently. From a confiding presence, a soaring sorrowful spirit, it becomes a hostile sentry  and a glowering, angry head. Finally, in the last years of his creative life it. is a crushed or swooning body, sucked into a giddy whirlpool'. In some of his last works Vrubel resurrects the figure as a massive head with tragic staring eyes: a pure spirit which looms out of the mist, dominant at last, but with its empire gone. Apart from his work on monumental painting, Vrubel had concentrated largely on water-colour during the last ten years of his life; he considered this medium to be the most exacting discipline.

and a glowering, angry head. Finally, in the last years of his creative life it. is a crushed or swooning body, sucked into a giddy whirlpool'. In some of his last works Vrubel resurrects the figure as a massive head with tragic staring eyes: a pure spirit which looms out of the mist, dominant at last, but with its empire gone. Apart from his work on monumental painting, Vrubel had concentrated largely on water-colour during the last ten years of his life; he considered this medium to be the most exacting discipline.

More than any other artist Vrubel was the inspiration to the "avant-garde" in Russia during the next twenty years. He might be termed the Russian Cezanne, for they share a number of characteristics: both artists bridge the centuries in their work, and not only the centuries, but the two visions which so radically divide the nineteenth century from the twentieth; "modern art" from the art of Europe since the Renaissance and the birth of "easel painting".

Most of Vrubel's drawings are studies of flowers, but not of flowers growing in the field in their natural environment; they are penetrating close-ups of the tangled interplay of forms, giving them in their artificial isolation a peculiar dramatic rhythm. Vrubel is at his greatest in these exquisite water-colour and pencil sketches. His searching pencil attacks the model from every viewpoint: in transparent interweaving patterns, in balancing mass against mass, in mosaic-like patterning. It is for this tireless, exhaustive examination of the possibilities of pictorial representation that the next generations so revered Vrubel, as well as for his extraordinary imaginative vision.

Vladimir Favorsky

Vladimir Favorsky (1886—1964) left his mark in many spheres of art. As a young man, he worked enthusiastically at easel painting and later retained a fondness for painting still-lifes and landscapes. Until the end of his days lie continued to enjoy pencil drawing, particularly portraits. His experiments in the sphere of monumental painting are also worth mentioning; they show a profound understanding of the indissoluble link between wall painting and architecture.

In spite of all this, Favorsky was undoubtedly first and foremost an engraver, and his medium was wood. It was to the wood engraving that he devoted the greatest effort and owed those great successes which secured for him one of the first places in modern art. Favorsky realised the fascination of the actual technique of the woodcut and wood engraving, the beauty of the material which the artist is called upon to reveal in the very process of imposing his own will upon it.

The chief place in Favorsky's work belongs to book illustration. This, however, did not prevent him from producing a number of wall prints (often in linoleum), in which he incorporated the experience gained from his work on books.

To appreciate the originality of Favorsky's engraving's, it is essential to bear in mind that he was never satisfied with the creation of illustrations as separate, graphic pictures not seen as integral parts of the printed page.

When beginning a series of illustrations, Favorsky usually worked from a preliminary design of the book he was planning. This design takes into account the size of the book, the width of the margins, cover and title page, initial letters and headpieces, the order in which the illustrations will be placed and any ornamentation within the text.

Favorsky uses his skill in composition not only in the designing of whole books and whole pages, but in the structure of each separate image. With great sensitivity he succeeds in expressing the essence of his subject by the very way in which the component parts fall into position. In the illustration to "The Lay of the

Host of Igor", which shows Igor at the beginning of the battle, the figures of the prince and his warriors are moved out into the immediate foreground, it is as though they were already advancing on the enemy, the black banner above their heads expresses the might of the Russian host. In the figure of the prince vertical lines dominate. The figures of his enemies are round the edges so that they are merely on the periphery of the main group. In the next print, showing the battle between the Russians and the Polovtsy, the distribution of figures is of quite a different character. Here, the galloping figure of Igor's ally prince Vse-volod is only glimpsed in the depths of the composition and the foreground is densely occupied by squat figures of the Polovtsy, who appear to have cut us off from the Russian host. The solemn, statuesque attitudes are replaced by the tempo of the gallop. With a few exceptions when he has recourse to colour Favorsky confines himself to the use of black, white and intermediary tones. So acute is his sensitivity to the mutual effects of dark and light that even in monochrome engravings he manages to create an illusion of colour harmony. In the Samarkand linocuts we feel the brilliance of the eastern weaves, in the Dante print the number "9" stands out like a scarlet initial, the black flag in "The Lay of the Host of Igor" creates the impression of a patch of colour.

Use one of the following topics for oral or written composition.

Use one of the following topics for oral or written composition.

1. Speak about the main features in the work of the most outstanding Russian portrait-painters, genre-painters and landscape-painters.

2. Make a report on your favourite Russian painter and describe one or two of his pictures.

3. Speak about the development of Russian painting in: a) the XVIII, b) the XIX and c) the XX centuries.

Date: 2015-01-02; view: 1613

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Valentin Serov | | | DESCRIBING A PAINTING |