CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

The one thing the English will never forgive the Germans for is 1 page

Working too hard.

GEORGE MIKES

This statement was written by a Hungarian humourist who emigrated to Britain in 1938. He wrote it in the 196os, when the German economy was rapidly overtaking Britain's. Living standards in Britain have risen steadily since then, but not as fast, perhaps, as they have in other EU countries. Britain used to be one of the wealthiest countries in Europe. These days it is often, by most standards of measurement, poorer than the EU average. (In fact, in 1992 it was even poor enough to qualify for special EU funding for poorer member states, though national pride prevented it from applying.)

Earning money

The statement above is, of course, not literally true. However, it does reflect a certain lack of enthusiasm for work in general. At the upper end of the social scale this attitude to work exists because leisure has always been the main outward sign of aristocracy. And because of Britain's class system, it has had its effects throughout society. If you have to work, then the less it looks like work the better. Traditionally therefore, a major sign of being middle class (as opposed to working class) has been that you do non-manual work. The fact that skilled manual (or 'blue-collar') workers have been paid more highly than the lower grades of'white-collar' (i.e. non-manual) worker for several decades has only slightly changed this social perception. This 'anti-work' outlook among the working class has led to a relative lack of ambition or enthusiasm and a belief that high earnings are more important than job satisfaction.

These attitudes are slowly changing. For example, at least half of the workforce now does non-manual work, and yet a majority describe themselves as working class (see chapter 4). It would therefore seem that the connection between being middle class and doing non-manual work is growing weaker. Nevertheless, the connection between class distinctions and types of work lives on in a number of ways. One illustration of this is the different way in which earnings

14 2 15 The economy and everyday life

| > Top people In Britain, particular occupations are no longer as closely associated with particular classes as they used to be. The feminist movement, the expansion of higher education and an egalitarian atmosphere have reduced the influence of old-established, male-dominated institutions such as public schools and Oxbridge (see chapter 14). A popular claim is that in modern Britain people achieve their positions by exercising their abilities rather than as a result of their backgrounds. In the early 1990s it was true that even the Prime Minister (John Major) had been educated at a state school and had left full-time education at the age of sixteen. However, there is a limit to these changes. In 1992 The Economist magazine drew up a list of the holders of 100 of the most important positions in the country (in politics, the civil service, the armed forces, academia, the arts, business and finance). The backgrounds of these 'top' people were then compared with those of people in similar positions in 1972. Here are the results: |

| > How they are paid |

|

| In both years two-thirds of the top people had been to public school (to which less than ^% of the population goes) and an astonishing proportion to just one of these. It was more important in 1992 to be highly educated than it was in 1972. But still half of all the top jobs were held by people from just two of the country's universities. And women are almost completely excluded (in both years' lists, one of those women was the Queen!). |

|

| are conventionally expressed and paid (> How they are paid). Another is the fact that certain organizations of professional workers, such as the National Union of Teachers (NUT), have never belonged to the Trades Union Congress (see below). The connection can also be seen if we look at those people who hold the most important jobs in the country (> Top people). Perhaps the traditional lack of enthusiasm for work is the reason why the working day, in comparison with most European countries, starts rather late (usually at eight o'clock for manual workers and around nine for non-manual workers). However, measured by the number of hours worked in a week, the British reputation for not working hard enough appears to be false (l> The industrious British). The normal lunch break is an hour or less, and most people (unless they work part-time) continue working until five or later. Many people often work several hours overtime a week. In addition, a comparatively large proportion of British people stay in the workforce for a comparatively large part of their lives. The normal retiring age for most people is sixty-five (sixty for some, including a greater proportion of women). There are three main ways in which people look for work in Britain: through newspapers (national ones for the highest-qualified, otherwise local ones), through the local job centre (which is run as a government service) and through privately-run employment agencies (which take a commission from employers). The overall trend in employment over the last quarter of the twentieth century has been basically the same as elsewhere in western Europe. The level of unemployment has gradually risen and most new job opportunities are in the service sector (in communications, health care and social care, for example). This situation has led to an interesting irony with regard to the two sexes. The decline of heavy industry means fewer jobs in stereotypical 'men's work', while the rise in service occupations means an increase in vacancies for stereotypical 'women's work'. In 1970 around 65% of all those in work in Britain were men. In 1993 men made up only 51% of the workforce. When the law against sex discrimination in employment was passed in 1975, it was intended |

Average length of working week (1989)

• full-time employees B full-time self-employed hours

Work organizations 143

Percent of population in the labour force (1989)

Those either in work or looking for work

| mainly to protect women. However, in 1994 nearly half of the complaints received by the Equal Opportunities Commission (which helps to enforce the law) came from men. In that year there were two-and-a-half times as many unemployed men as there were unemployed women. Many men now seek employment as nurses, child carers, shop assistants, secretaries and other kinds of office worker. But they often find that, for no justifiable reason, they are not hired. It seems that these jobs are still considered to be more suitable for women. One of the reasons for this may be the low rates of pay in these areas of work. Although it is illegal for women to be paid less than men for the same job, in 1993 the average full-time male employee earned about 50% more than the average full-time female worker. Work organizations The organization which represents employers in private industry is called the Confederation of British Industry (CBI). Most employers belong to it and so the advice which it gives to trade unions and the government is quite influential. The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a voluntary association of the country's trade unions. There are more than a hundred of these, representing employees in all types of business. Most British unions are connected with particular occupations. Many belong to the Labour party (see chapter 6) to which their members pay a 'political levy'. That is, a small part of their union membership subscription is passed on to the party, although they have the right to 'contract out' of this arrangement if they want to. However, the unions themselves are not usually formed along party lines; that is, there is usually only one union for each group of |

| > The industrious British The British may not like work very much. But they seem to spend a lot of time doing it. Look at the European comparisons above. The figures show that in Britain, full-time employees work the longest ,hours in Europe, self-employed people work longer than in most other European countries and more people between the ages of twenty-five and sixty, especially women, stay in 'the job market' than they do in most other European countries. Moreover, holiday periods in Britain are comparatively short and the country has a comparatively small number of public holidays (see chapter 23). |

144 15 The economy and everyday life

| > Labour relations: a glossary When there is a dispute between employees and management, the matter sometimes goes toarbitration; that is, both sides agree to let an independent investigator settle the dispute for them. Refusing to work in the normal way is generally referred to as industrial action (even when the work has nothing to do with industry). This can take various forms. One of these is awork-to-rule, in which employees follow the regulations concerning their jobs exactly and refuse to be flexible or co-operative in the normal way. Another is ago slow. Finally, the employees might go on strike. Strikes can be official, if all the procedures required to make them legal have taken place, or unofficial (when they are sometimes referred to as wildcat strikes). When there is a strike, some strikers act as pickets. They stand at the entrance to the worksite and try to dissuade any fellow-workers who might not want to strike (whom they call blacklegs) from going into work. |

|

| employees rather than a separate one for each political party within that group. Unions have local branches, some of which are called 'chapels', reflecting a historical link with nonconformism (see chapter 13). At the work site, a union is represented by a shop steward, who negotiates with the on-site management. His (very rarely is it 'her') struggles with the foreman, the management-appointed overseer, became part of twentieth century folklore. Union membership has been declining since 1979 (> The decline of the unions). Immediately before then, the leader of the TUC (its General Secretary) was one of the most powerful people in the country and was regularly consulted by the Prime Minister and other important government figures. At that time the members of unions belonging to the TUC made up more than half of all employed people in the country. But a large section of the public became disillusioned with the power of the unions and the government then passed laws to restrict this power. Perhaps the decline in union membership is inevitable in view of the history of British unions as organizations for full-time male industrial workers. To the increasing numbers of . female and part-time workers in the workforce, the traditional structure of British unionism has seemed less relevant. In an effort to halt the decline, the TUC declared in 19 94 that it was loosening its contacts with the Labour party and was going to forge closer contacts with other parties. One other work organization needs special mention. This is the National Union of Farmers (NUF). It does not belong to the TUC, being made up mostly of agricultural employers and independent farmers. Considering the small number of people involved in agriculture in Britain (the smallest proportion in the whole of the EU), it has a remarkably large influence. This is perhaps because of the special fascination that 'the land' holds for most British people (see chapter ^), making it relatively easy for the NUF to make its demands heard, and also because many of its members are wealthy. |

The structure of trade and industry 145

| The structure of trade and industry The 'modernization* of business and industry happened later in Britain than it did in most other European countries. It was not until the 19605 that large corporations started to dominate and that a 'management class', trained at business school, began to emerge. Even after that time, many companies still preferred to recruit their managers from people who had 'worked their way up' through the company ranks and/or who were personally known to the directors. Only in the 1980s did graduate business qualifications become the norm for newly-hired managers. British industry performed poorly during the decades following the Second World War (some people blamed this on the above characteristics). In contrast, British agriculture was very successful. In this industry, large scale organization (i.e. big farms) had been more common in Britain than in other European countries for quite a long time. As in all European countries, the economic system in Britain is a mixture of private and public enterprise. Exactly how much of the country's economy is controlled by the state has fluctuated a great deal in the last fifty years and has been the subject of continual political debate. From 1945 until 1980 the general trend was for the state to have more and more control. Various industries became nationalized (in other words, owned by the government), especially those concerned with the production and distribution of energy. So too did the various forms of transport and communication services (as well, of course, as the provision of education, social welfare and health care). By 1980, 'pure' capitalism probably formed a smaller part of the economy than in any other country in western Europe. From 1980 the trend started going in the other direction. A major part of the philosophy of the Conservative government of the 198os was to let 'market forces' rule (which meant restricting the freedom of business as little as possible) and to turn state-owned companies into companies owned by individuals (who became shareholders). This approach was a major part of the thinking of Thatcherism (Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister at that time). Between 1980 and 1994 a large number of companies were privatized (or 'denationalized'). That is, they were sold off by the government. By 1988 there were more shareholders in the country than there were members of unions. In addition, local government authorities were encouraged to 'contract out' their responsibility for services to commercial organizations. The privatization of services which western people now regard as essential has necessitated the creation of various public 'watchdog' organizations with regulatory powers over the industries which they monitor. For example, Offtel monitors the activities of the privatized telephone industry, and Off Wat monitors the privatized water companies. |

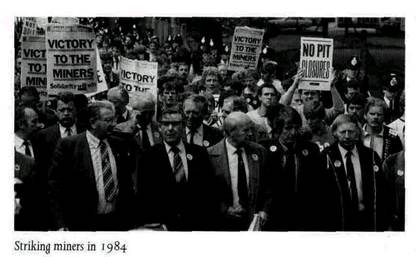

| > The decline of the unions In the 19805 the British government passed several laws to restrict the power of the unions. One of these abolished the 'closed shop' (an arrangement which employers made with unions to hire only people who belonged to a union). Another made strikes illegal unless a postal vote of all union members had been conducted. In 1984 there was a long miners' strike. The National Union of Miners refused to follow the new regulations. Its leader, Arthur Scargill, became a symbol (depending on your point of view) of either all the worst lunacies of unionism or the brave fight of the working classes against the rise of Thatcherism. Previous miners' strikes in the twentieth century had been mostly successful. But this one was not (the miners did not achieve their aims); a sign of the decline in union power. Here is another sign (the TUC is the Trades Union Congress, the national association of trade unions): Total membership of the TUC millions |

|

| 146 > The widening gap between rich and poor |

| £0.50 -\ |

|

| Source: Social Trends 1994 The graph shows that for every pound that the poorest 20% of the population in Britain had in 1978, most people had two pounds and the richest 20% of the population had three pounds. In 1994 the gap in wealth had grown. The richest people were about 50% richer, and most people were about 25'% richer. The poorest people had, however, become slightly poorer. > Collecting taxes The government organization which is responsible for collecting taxes in Britain is called the Inland Revenue. For employees, paying their income tax is not something they have to worry about. It is deducted from their pay cheque or pay packet before they receive it. This system is known as PAYE ( = pay as you earn), The tax added to the price of something you buy is called VAT (= value added tax). |

| The distribution of wealth In the early 1970s Britain had one of the most equitable distributio: of wealth in western Europe. By the early 1990s it had one of the least equitable. The rich had got richer but the poor had not. Some surveys suggested that, by this time, the gap between the richest 10% of the population and the poorest 10% was as great as it had been in the late nineteenth century and that large numbers of house holds were living below the 'poverty line', which meant that they did not have enough money for basic things such as food and heating. Class and wealth do not run parallel in Britain (see chapter 4), so it is not a country where people are especially keen to flaunt their wealth. Similarly, people are generally not ashamed to be poor. Of course, they don't like being poor, but they do not feel obliged to hide the fact. This can sometimes lead to an acceptance of poverty which is surprising for an 'advanced' country. When, in 1992, new of its increasing extent came to wider public attention, the government neither pretended that greater poverty did not exist, nor promised to do anything radical about it. Instead, it issued, through the Ministry of Agriculture, a suggested diet which it claimed even the poorest could afford. There were, of course, public comments about the patronizing nature of this action, but criticism in the press concentrated on how unrealistic the diet was, on how the figures didn't add up (and on the mystery of how a person should prepare and eat the recommended half an egg a week!). One reason for the increasing disparity of wealth in Britain in the 1970s and 1980s is that rates of income tax changed. For a short period in the 1960s the basic rate was 40%. By the early eighties it was 30% and it then went down to 25%. During the same period, the top rate of income tax fell from a high of 98% to 40%. Of course, these figures do not mean that this is how much is deducted from a person s earnings. People in different situations are allowed to earn varying amounts before tax is deducted. People earning twice the average wage have about 25% of their gross income deducted. Somebody earning less than half the average wage pays very little tax at all. Nevertheless, there is, at the time of writing, a great disparity in different people's 'take-home pay'. During the 1980s, rates of pay for the best-paid jobs increased faster than those for badly-paid jobs. People in the best-paid jobs now take home about ten times as much as those in the lowest paid jobs. Many company directors, for example, take home seven times as much as the average wage. Finance and investment Wealth (and poverty) are relative concepts. Despite its relative economic decline, Britain is still one of the wealthiest places in the world. The empire has gone, the great manufacturing industries have |

Finance and investment 147

| nearly gone, but London is still one of the centres of the financial world. The Financial Times-Stock Exchange (FT-SE) Index of the 100 largest British companies (known popularly as the 'Footsie') is one of the main indicators of world stock market prices. The reason for this is not hard to find. The same features that contributed to the country's decline as a great industrial and political power — the preference for continuity and tradition rather than change, the emphasis on personal contact as opposed to demonstrated ability when deciding who gets the important jobs — are exactly the qualities that attract investors. When people want to invest a lot of money, what matters to them is an atmosphere of stability and a feeling of personal trust. These are the qualities to be found in the 'square mile' of the old City of London (see chapter 3), which has one of the largest concentrations of insurance companies, merchant banks, joint-stock banks and stockbrokers in the world. As regards stability, many of the institutions in what is known as 'the City' can point to a long and uninterrupted history. Some of them have directors from the same family which started them perhaps over 200 years ago. Although there have been adaptations to modern conditions, and the stereotyped bowler-hatted 'city gent' is a thing of the past, the sense of continuity, epitomized by the many old buildings in the square mile, is still strong. As regards trust, the city has a reputation for habits of secrecy that might be thought of as undesirable in other aspects of public life, but which in financial dealings become an advantage. In this context, 'secrecy' means 'discretion'. Although more than half of the British population has money invested in the city indirectly (because the insurance companies and pension funds to which they have entrusted their money invest it on the stock market), most people are unaware of what goes on in the world of 'high finance'. To most people, money is just a matter of the cash in their pockets and their account with one of the 'high street' banks (> The high street banks). Not every adult has a bank account. In 1970 only about 30% used these banks. But with the increasing habit of paying wages by cheque and the advent of cash dispensing machines, a majority now do so. Many, however, still prefer to use their National Savings account at the post office or one of the country's many building societies (see chapter 19). An indication of the importance of bank accounts in people's lives is the strong dislike of the banks that has developed. During the 1990s the newspapers carried horror stories about their practices. In the years 1988 to 1993 banking profits rose by 50% while charges to customers rose by 70%. It is often difficult for people to do anything about bank charges — if they try to discuss them with their bank, they get charged for the phone calls and letters! So far, the one clear improvement has been in bank opening times. These used to be from nine-thirty to three-thirty, Mondays to Fridays only. Now, many banks stay open later and also open on Saturday mornings. |

| > The old lady ofThreadneedle Street This is the nickname of the Bank of England, the institution which controls the supply of money in Britain and which is located, of course, in the 'square mile'. Notice how the name suggests both familiarity and age - and also conservative habits. The bank has been described as 'fascinated by its own past'. It is also notable that the people who work there are reported to be proud of the nickname. |

|

| > The high street banks The so-called 'big four' banks, which each have a branch in almost every town in Britain are: the National Westminster Bank (NatWest); Barclays Bank; Lloyds Bank; Midland Bank. The Bank of Scotland also has a very large number of branches. So does the Trustee Savings Bank (TSB). |

|

> Currency and cash

The currency of Britain is the pound

sterling, whose symbol is'£', always written before the amount. Informally, a pound is sometimes called a 'quid', so £20 might be expressed as 'twenty quid'. There are 100 pence (written 'p', pronounced 'pea') in a pound.

The one-pound coin has four different designs: an English one, a . Scottish one, a Northern Irish one and a Welsh one (on which the inscription on the side is in Welsh;

on all the others it is in Latin).

In Scotland, banknotes with a Scottish design are issued. These notes are perfectly legal in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, but banks and shops are not obliged to accept them if they don't want to and nobody has the right to demand change in Scottish notes.

Before 1971 Britain used the 'LSD' system. There were twelve pennies in a shilling and twenty shillings in a pound. Amounts were written like this: £3 12s. 6d. (= three pounds, twelve shillings and sixpence). If you read any novels set in Britain before 1971, you may come across the following:

a farthing = a quarter of a penny

(not used after 1960) a ha'penny (halfpenny) = half of a

penny

a threepenny bit = threepence a tanner = an informal name for a sixpenny coin a bob = an informal name for ashilling a half crown = two-and-a-half shillings (or two and sixpence)

People were not enthusiastic about the change to what they called 'new money'. For a long time afterwards, the question 'what's that in old money?' was used to imply that what somebody had just said was too complicated to be clear. In fact, money provides frequent opportunities for British conservatism (see a chapter ^) to show itself. When the one-pound coin was introduced in 1983, it was very unpopular. People said they were sad to see the end of the pound note, which it replaced, and that a mere coin didn't seem to be worth as much. Another example is the reaction to the European euro. Since 1991 this has had the same status in Britain as Scottish banknotes have in England. But the first signs were that most shops and banks were refusing to accept them.

| > How much do you want? On tins and packets of food in British shops, the weight of an item is written in the kilos and grams familiar to people from continental Europe. However, most British people have little idea of what these terms mean (see chapter s). Therefore, many of their packets and tins also record their weight in pounds (written as 'Ibs') and ounces (written as 'oz'). Moreover, nobody ever asks for a kilo of apples or 200 grams of cheese. If those were the amounts you wanted, you would have to ask for 'two pounds or so' of apples and 'half a pound or less' of cheese and you would be about right. Shoe and clothing sizes are also measured on different scales in Britain. The people who work in shops which sell these things usually know about continental and American sizes too, but most British people don't. |

| Spending money: shopping The British are not very adventurous shoppers. They like reliability and buy brand-name goods wherever possible, preferably with the price clearly marked (they are not very keen on haggling over prices). It is therefore not surprising that a very high proportion of the country's shops are branches of chain stores. Visitors from northern European countries are sometimes surprised by the shabbiness of shop-window displays, even in prosperous areas. This is not necessarily a sign of economic depression. It is just that the British do not demand art in their shop windows. In general, they have been rather slow to take on the idea that shopping might actually be fun. On the positive side, visitors are also sometimes struck by the variety of types of shop. Most shops are chain stores, but among those that are not, there is much individuality. Independent shopowners feel no need to follow conventional ideas about what a particular shop does and doesn't sell. In the last quarter of the twentieth century supermarkets began moving out of town, where there was lots of free parking space. As they did so, they became bigger, turning into 'hypermarkets' stocking a wider variety of items. For example, most of them now sell alcoholic drinks, which are conventionally bought at shops called 'off-licences'. They also sell petrol and some items traditionally found in chemists and newsagents. However, this trend has not gone as far as it has in some other European countries. For example, few supermarkets sell clothes, |

Date: 2015-12-18; view: 3623

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| There are no important official or | | | The one thing the English will never forgive the Germans for is 2 page |