CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother 2 page

86 8 The government

| ^Whitehall This is the name of the street in London which runs from Trafalgar Square to the Houses of Parliament. The Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Ministry of Defence are both located here. These are the two oldest government departments. The term 'Whitehall' is sometimes used to refer to the government as a whole (although other departments are in other streets nearby). This is done when the writer or speaker wishes to emphasize the administrative aspects of government. The phrase, 'the opinion in Whitehall...' refers not only to the opinions of government ministers but also, and perhaps more so, to the opinions of senior civil servants. |

|

| that four government ministers 'verbally abused' their civil service advisers and generally treated them 'with contempt'. It was the first time that such a complaint had been made. It seemed that the unpre-cedentedly long period of government by the same party (the Conservatives - see chapter 10) had shifted the traditional balance of power. However, the British civil service has a (largely) deserved reputation for absolute political impartiality. Many ministers have remarked on the struggle for power between them and their top civil servants, but very few have ever complained of any political bias. Top civil servants know that their power depends on their staying out of'politics' and on their being absolutely loyal to their present minister. Modern criticism of the civil service does not question its loyalty but its efficiency. Despite reforms, the top rank of the civil service is still largely made up of people from the same narrow section of society - people who have been to public school (see chapter 14) and then on to Oxford or Cambridge, where they studied subjects such as history or classical languages. The criticism is therefore that the civil service does not have enough expertise in matters such as economics or technology, and that it lives too much in its own closed world, cut off from the concerns of most people in society. In the late twentieth century, ministers tried to overcome these perceived deficiencies by appointing experts from outside the civil service to work on various projects and by having their own political advisers working alongside (or, some would say, in competition with) their civil servants. Central and local government Some countries, such as the USA and Canada, are federal. They are made up of a number of states, each of which has its own government with its own powers to make laws and collect taxes. In these countries the central governments have powers only because the states have given them powers. In Britain it is the other way around. Local government authorities (generally known as 'councils') only have powers because the central government has given them powers. Indeed, they only exist because the central government allows them to exist. Several times in the last hundred years British governments have reorganized local government, abolishing some local councils and bringing new ones into existence. The system of local government is very similar to the system of national government. There are elected representatives, called councillors (the equivalent of MPs). They meet in a council chamber in the Town Hall or County Hall (the equivalent of Parliament), where they make policy which is implemented by local government officers (the equivalent of civil servants). | |

Central and local government 87

|

| „,-.,....,, I BELFAST 14 FERMANAGH Key to England and Wales , newtownabbey 15 OMAGH ^ 1 WEST YORKSHIRE1} BEDFOMSHIIIE 3 CARRICKFERGUS 16 COOKSTOWN 2 GKEATER MANCHESTEK 14 BUCKINGHAMSHIRE 4 CASTLEREAGH 17 MAGHERAFELT 3 SOUTH YORKSHIRE 15 GLOUCESTERSHIRE 5 NORTH DOWN 18 STRABANE 4 DERBYSHIRE 16 HERTFORDSHIRE 6 ARDS 19 DERRY 5 NOTTINGHAMSHIRE17 OXFORDSHIRE 7 DOWN 20 LIMAVADY 6 STAFFORDSHIRE18 GREATER LONDON (see inset) 8 NEWRY AND MOURNE 21 COLERAINE 7 LEICESTERSHIRE 19 BERKSHIRE 9 BANBRIDGE 22 BALLYMONEY 8 WEST MIDLANDS 20 HAMPSHIRE 10 LISBURN 23 MOYLE 9 CAMBRIDGESHIRE 21 WILTSHIRE II CRAIGAVON 24 BALLYMENA 10 NORTHAMPTONSHIRE 22 GWENT 12 ARMAGH 25 LARNE 11 WARWICKSHIRE 23 MID GLAMORGAN 13 DUNGANNON 26 ANTRIM 12 HEREFORD AND WORCESTER 24 SOUTH GLAMORGAN © Oxford University Press Most British people have far more direct dealings with local government than they do with national government. Local councils traditionally manage nearly all public services. Taken together, they employ three times as many people as the national government does. In addition, there is no system in Britain whereby a national government official has responsibility for a particular geographical area. (There is no one like a 'prefect' or 'governor'). In practice, therefore, local councils have traditionally been fairly free from constant central interference in their day to day work. Local councils are allowed to collect one kind of tax. This is a tax based on property. (All other kinds are collected by central government.) It used to be called 'rates' and was paid only by those who owned property. Its amount varied according to the size and location of the property. In the early 1990 s it was replaced by the 'community charge' (known as the 'poll tax'). This charge was the |

| > Counties, boroughs, parishes Counties are the oldest divisions of the country in England and Wales. Most of them existed before the Norman conquest (see chapter 2). They are still used today for local government purposes, although a few have been 'invented' more recently (e.g. Humberside) and others have no function in government but are still used for other purposes. One of these is Middlesex, which covers the western part of Greater London (letters are still addressed 'Middx.') and which is the name of a top-class cricket team. Many counties have 'shire' in their name (e.g. Hertfordshire, Hampshire, Leicestershire). 'Shires' is what the counties were originally called. Boroughs were originally towns that had grown large and important enough to be given their own government, free of control by the county. These days, the name is used for local government purposes only in London, but many towns still proudly describe themselves as Royal Boroughs. Parishes were originally villages centred on a local church. They became a unit of local government in the nineteenth century. Today they are the smallest unit of local government in England. The name 'parish' is still used in the organization of the main Christian churches in England (see chapter 13). |

88 8 The government

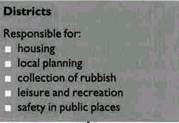

| same for everybody who lived in the area covered by a council. It was very unpopular and was quickly replaced by the 'council tax', which is based on the estimated value of a property and the number of people living in it. Local councils are unable to raise enough money in this way for them to provide the services which central government has told them to provide. In addition, recent governments have imposed upper limits on the amount of council tax that councils can charge and now collect the taxes on business properties themselves (and then share the money out between local councils). As a result, well over half of a local council's income is now given to it by central government. The modern trend has been towards greater and greater control by central government. This is not just a matter of controlling the way local government raises money. Thereare now more laws governing the way councils can conduct their affairs. On top of this, schools and hospitals can now 'opt out' of local-government control (see chapters 14 and 18). Perhaps this trend is inevitable now that national party politics dominates local politics. Successful independent candidates (candidates who do not belong to a political party) at local elections are becoming rarer and rarer. Most people now vote at local elections according to their national party preferences, if they bother to vote at all, so that these elections become a kind of opinion poll on the performance of the national government. Local government services Most of the numerous services that a modem government provides are run at local level in Britain. These include public hygiene and environmental health inspection, the collecting of rubbish from outside people's houses (the people who do this are euphemistically known as 'dustmen'), and the cleaning and tidying of all public places (which is done by 'street sweepers') (> The organization of local government). They also include the provision of public swimming pools, which charge admission fees, and public parks, which do not. The latter are mostly just green grassy spaces, but they often contain children's playgrounds and playing fields for sports such as football and cricket which can be reserved in advance on payment. Public libraries are another well-known service (> Public libraries). Anybody can go into one of these to consult the books, newspapers and magazines there free of charge. If you want to borrow books and take them out of the library, you have to have a library card or ticket (these are available to people living in the area). Sometimes CDs and video cassettes are also available for hire. The popularity of libraries in Britain is indicated by the fact that, in a country without identity cards (see chapter 6), a person's library card is the most common means of identification for someone who does not have a driving licence. |

| > The Greater London Council The story of the Greater London Council (GLC) is an example of the struggle for power between central and local government. In the early 1980s Britain had a right-wing Conservative government. At a time when this government was unpopular, the left-wing Labour party in London won the local election and gained control of the GLC. The Labour-controlled GLC then introduced many measures which the national government did not like (for example, it reduced fares on London's buses and increased local taxes to pay for this). The government decided to abolish the GLC. Using its majority in the House of Commons, it was able to do this. The powers of the GLC were either given to the thirty-two boroughs of London ,or to special commitees. It was not until the year 2000 that a single governmental authority for the whole of London came into existence again and the city got its first ever direcdy-elected mayor. > Public libraries In comparison with the people of other western countries, the British public buy relatively few books. However, this does not necessarily mean that they read less. There are about 5,000 public libraries in Britain (that's about one for every 12,000 people). On average, each one houses around 45,000 books. A recent survey showed that 70% of children between the ages of four and sixteen use their local library at least twice a month, and that 5 1 % of them use it once a week or more. In addition, and unfortunately, many British people seem to prefer , libraries to bookshops even when they want to own a book. Nearly nine million books are stolen from the shelves of libraries every year. |

Questions and suggestions 8 9

The organization of local government (1995)

|

|

|

QUESTIONS

1 Do you think the theory of collective responsibility is a good one? Does it exist in your country?

2 What would be the equivalent titles in your country for: Chancellor, Home Secretary, Foreign Secretary?

3 A British Prime Minister has no status in law which puts him or her above other politicians. So why are modern British PMs so powerful?

4 How does the relationship between central and local government in Britain compare with that in your country?

5 Local government in Britain is responsible for most of the things that affect people in everyday life. So why do you think so few people bother to vote in local elections in Britain?

SUGGESTIONS

• Margaret Thatcher (Prime Minister from 1979 to 1990) has been the subject

of several biographical studies which offer insights into the workings of government. For example, One of us by Hugo Young (Pan Books).

| Parliament |

The activities of Parliament in Britain are more or less the same as those of the Parliament in any western democracy. It makes new laws, gives authority for the government to raise and spend money, keeps a close eye on government activities and discusses those activities.

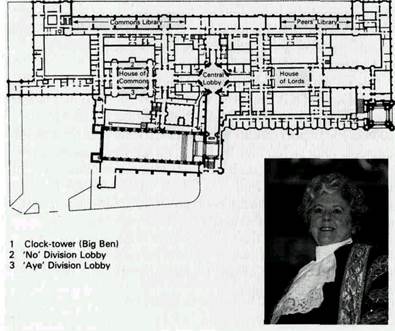

The British Parliament works in a largebuilding called the Palace of Westminster (popularly known as 'the Houses of Parliament'). This contains offices, committee rooms, restaurants, bars, libraries and even some places of residence. It also contains two larger rooms. One of these is where the House of Lords meets, the other is where the House of Commons meets. The British Parliament is divided into two 'houses', and its members belong to one or other of them, although only members of the Commons are normally known as MPs (Members of Parliament). The Commons is by far the more important of the two houses.

The atmosphere of Parliament 91

| The atmosphere of Parliament Look at the picture of the inside of the meeting room of the House of Commons (i> The House of Commons). Its design and layout differ from the interior of the parliament buildings in most other countries. These differences can tell us a lot about what is distinctive about the British Parliament. First, notice the seating arrangements. There are just two rows of benches facing each other. On the left of the picture are the government benches, where the MPs of the governing party sit. On the right are the opposition benches. There is no opportunity in this layout for a reflection of all the various shades of political opinion (as there is with a semi-circle). According to where they sit, MPs are seen to be either 'for' the government (supporting it) or against it. This physical division is emphasized by the table on the floor of the House between the two rows of benches. The Speaker's chair, which is raised some way off the floor, is also here. From this commanding position, the Speaker chairs (that is, controls) the debates (> The Speaker). The arrangement of the benches encourages confrontation between government and opposition. It also reinforces psychologically the reality of the British two-party system (see chapter 6). There are no 'cross-benches' for MPs who belong neither to the governing party nor the main opposition party. In practice, these MPs sit on the opposition benches furthest from the Speaker's chair (at the bottom right of the picture). Plan of the Palace of Westminster (principal floor) |

|

| > The Speaker Anybody who happened to be watching the live broadcast of Parliament on 27 April 1992 was able to witness an extraordinary spectacle. A female MP was physically dragged, apparently against her will, out of her seat on the back benches by fellow MPs and was forced to sit in the large chair in the middle of the House of Commons. What the House of Commons was actually doing was appointing a new Speaker. The Speaker is the person who chairs and controls discussion in the House, decides which MP is going to speak next and makes sure that the rules of procedure are followed. (If they are not, the Speaker has the power to demand a public apology from an MP or even to ban an MP from the House for a number of days). It is a very important position. In fact, the Speaker is, officially, the second most important 'commoner' (non-aristocrat) in the kingdom after the Prime Minister. Hundreds of years ago, it was the Speaker's job to communicate the decisions of the Commons to the King (that is where the title 'Speaker' comes from). As the king was often very displeased with what the Commons had decided, this was not a pleasant task. As a result, nobody wanted the job. They had to be forced to take it. These days, the position is a much safer one, but the tradition of dragging an unwilling Speaker to the chair has remained. The occasion in 1992 was the first time that a woman had been appointed Speaker, so that MPs had to get used to addressing not 'Mr Speaker', as they had always done in the past, but "Madam Speaker' instead. Once a Speaker has been appointed, he or she agrees to give up all party politics and remains in the job for as long as he or she wants it. Betty Boothroyd, the first woman Speaker of the House of Commons |

| 92 9Parliament |

Second, the Commons has no 'front', no obvious place from which an MP can address everybody there. MPs simply stand up and speak from wherever they happen to be sitting. Third, notice that there are no desks for the MPs. The benches where they sit are exactly and only that - benches, just as in a church. This makes it physically easy for them to drift in and out of the room, which is something that they frequently do during debates. Fourth, notice that the House is very small. In fact, there isn't enough room for all the MPs. There are more than 6^0 of them, but there is seating for less than 400. A candidate at an election is said to have won *a seat* in the Commons, but this 'seat' is imaginary. MPs do not have their 'own' place to sit. No names are marked on the benches. MPs just sit down wherever (on 'their' side of the House) they can find room.

All these features result in a fairly informal atmosphere. Individual MPs, without their own 'territory' (which a personal seat and desk would give them), are encouraged to co-operate. Moreover, the small size of the House, together with the lack of a podium or dais from which to address it, means that MPs do not normally speak in the way that they would at a large public rally. MPs normally speak in a conversational tone, and because they have nowhere to place their notes while speaking, they do not normally speak for very long either! It is only on particularly important occasions, when all the MPs are present, that passionate oratory is sometimes used.

One more thing should be noted about the design of the House of Commons. It is deliberate. Historically, it was an accident: in medieval times, the Commons met in a church and churches of that time often had rows of benches facing each other. But after the House was badly damaged by bombing in 1941, it was deliberately rebuilt to the old pattern (with one or two modern comforts such as central heating added). This was because of a belief in the two-way 'for and against' tradition, and also because of a more general desire for continuity.

The ancient habits are preserved today in the many customs and detailed rules of procedure which all new MPs find that they have to learn. The most noticeable of these is the rule that forbids MPs to address one another directly or use personal names. All remarks and questions must go 'through the Chair'. An MP who is speaking refers to or asks a question of 'the honourable Member for Winchester' or 'my right honourable friend'. The MP for Winchester may be sitting directly opposite, but the MP never says 'you'. These ancient rules were originally formulated to take the 'heat' out of debate and decrease the possibility that violence might break out. Today, they lend a touch of formality which balances the informal aspects of the Commons and further increases the feeling of MPs that they belong to a special group of people.

AnMP'slife 93

| An MPs life The comparative informality of the Commons may partly result from the British belief in amateurism. Traditionally, MPs were not supposed to be specialist politicians. They were supposed to be ordinary people giving some of their time to representing the people. Ideally, they came from all walks of life, bringing their experience of the everyday world into Parliament with them. This is why MPs were not even paid until the early twentieth century. Traditionally, they were supposed to be doing a public service, not making a career for themselves. Of course, this tradition meant that only rich people could afford to be MPs so that, although they did indeed come from a wide variety of backgrounds, these were always backgrounds of power and wealth. Even now, British MPs do not get paid very much in comparison with many of their European counterparts. Moreover, by European standards, they have incredibly poor facilities. Most MPs have to share an office and a secretary with two or more other MPs. The ideal of the talented amateur does not, of course, reflect modern reality. Politics in Britain in the last forty years has become professional. Most MPs are full-time politicians, and do another job, if at all, only part-time. But the amateur tradition is still reflected in the hours of business of the Commons. They are 'gentleman's hours'. The House does not sit in the morning. This is when, in the traditional ideal, MPs would be doing their ordinary work or pursuing other interests outside Parliament. From Monday to Thursday, the House does not start its business until 14.30 (on Friday it starts in the morning, but then finishes in the early afternoon for the weekend). It also gives itself long holidays: four weeks at Christmas, two each at Easter and Whitsun (Pentecost), and about eleven weeks in the summer (from the beginning of August until the middle of October). But this apparently easy life is misleading. In fact, the average modern MP spends more time at work than any other professional in the country. From Monday to Thursday, the Commons never 'rises' (i.e. finishes work for the day) before 22.30 and sometimes it continues sitting for several hours longer. Occasionally, it debates through most of the night. The Commons, in fact, spends a greater total amount of time sitting each year than any other Parliament in Europe. MPs' mornings are taken up with committee work, research, preparing speeches and dealing with the problems of constituents (the people they represent). Weekends are not free for MPs either. They are expected to visit their constituencies (the areas they represent) and listen to the problems of anybody who wants to see them. It is an extremely busy life that leaves little time for pursuing another career. It does not leave MPs much time for their families either. Politicians have a higher rate of divorce than the (already high) national average. |

| >Hansard This is the name given to the daily verbatim reports of everything that has been said in the Commons. They are published within forty-eight hours of the day they cover. |

| > The parliamentary day in the Commons from Mondays to Thursdays 14.30 Prayers 14.35 Question time 15•30 Any miscellaneous business, such as a statement from a minister, after which the main business of the day begins. On more than half of the days, this means a debate on a proposal for a new law, known as a 'bill'. Most of these bills are introduced by the government but some days in each year are reserved for 'private members' bills'; that is, proposals for laws made by individual MPs. Not many of these become law, because there is not enough interest among other MPs and not enough time for proper discussion of them. 22.00 Motion on the adjournment: the main business of the day stops and MPs are allowed to bring up another matter for general discussion. 22.30 The House rises (usually). |

94 9Parliament

| > Frontbenchers and backbenchers Although MPs do not have their own personal seats in the Commons, there are two seating areas reserved for particular MPs. These areas are the front benches on either side of the House. These benches are where the leading members of the governing party (i.e. ministers) and the leading members of the main opposition party sit. These people are thus known as 'frontbenchers'. MPs who do not hold a government post or a post in the shadow cabinet (see chapter 8) are known as "backbenchers'. |

| Parliamentary business The basic procedure for business in the Commons is a debate on a particular proposal, followed by a resolution which either accepts or rejects this proposal. Sometimes the resolution just expresses a viewpoint, but most often it is a matter of framing a new law or of approving (or not approving) government plans to raise taxes or spend money in certain ways. Occasionally, there is no need to take a vote, but there usually is, and at such times there is a 'division'. That is, MPs have to vote for or against a particular proposal. They do this by walking through one of two corridors at the side of the House — one is for the 'Ayes' (those who agree with the proposal) and the other is for the 'Noes' (those who disagree). But the resolutions of the Commons are only part of its activities. There are also the committees. Some committees are appointed to examine particular proposals for laws, but there are also permanent committees whose job is to investigate the activities of government in a particular field. These committees comprise about forty members and are formed to reflect the relative strengths of the parties in the Commons as a whole. They have the power to call certain people, such as civil servants, to come and answer their questions. They are becoming a more and more important part of the business of the Commons. The party system in Parliament Most divisions take place along party lines. MPs know that they owe their position to their party, so they nearly always vote the way that their party tells them to. The people who make sure that MPs do this are called the Whips. Each of the two major parties has several MPs who perform this role. It is their job to inform all MPs in their party how they should vote. By tradition, if the government loses a vote in Parliament on a very important matter, it hasto resign. Therefore, when there is a division on such a matter, MPs are expected to go to the House and vote even if they have not been there during the debate. The Whips act as intermediaries between the backbenchers and the frontbench (i> Frontbenchers and backbenchers) of a party. They keep the party leadership informed about backbench opinion. They are powerful people. Because they 'have the ear' of the party leaders, they can have an effect on which backbenchers get promoted to the front bench and which do not. For reasons such as this, 'rebellions' among a group of a party's MPs (in which they vote against their party) are very rare. Sometimes the major parties allow a 'free vote', when MPs vote according to their own beliefs and not according to party policy. Some quite important decisions, such as the abolition of the death penalty and the decision to allow television cameras into the Commons, have been made in this way. |

The party system in Parliament 97

|

| Tony Blair, Prime Minister from 1997, answering questions in the House of Commons |

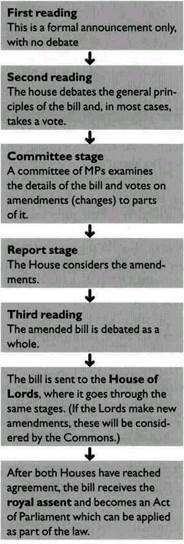

| > How a bill becomes a law Before a proposal for a new law starts its progress through Parliament, there will have been much discussion. If it is a government proposal, Green and White Papers will probably have been published, explaining the ideas behind the proposal. After this, lawyers draft the proposal into a bill. Most bills begin life in the House of Commons, where they go through a number of stages. |

| > Question time This is the most well-attended, and usually the noisiest, part of the parliamentary day. For about an hour there is no subject for debate. Instead, MPs are allowed to ask questions of government ministers. In this way they can, in theory at least, force the government to make certain facts public and to make its intentions clear. Opposition MPs in particular have an opportunity to make government ministers look incompetent or perhaps dishonest. The questions and answers, however, are not spontaneous. Questions to ministers have to be 'tabled' (written down and placed on the table below the Speaker's chair) two days in advance, so that ministers have time to prepare their answers. In this way the government can usually avoid major embarrassment. The trick, though, is to ask an unexpected "supplementary" question. After the minister has answered the tabled question, the MP who originally tabled it is allowed to ask a further question relating to the minister's answer. In this way, it is sometimes possible for MPs to catch a minister unprepared. Question time has been widely copied around the world. It is also probably the aspect of Parliament most well-known among the general public. The vast majority of television news excerpts of Parliament are taken from this period of its day. Especially common is for the news to show an excerpt from the half-hour on Wednesdays when it is the Prime Minister's turn to answer questions. |

|

Date: 2015-12-18; view: 2366

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother 1 page | | | Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother 3 page |