CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Caledonia, Cambria and Hibemia 3 page

The National Health Service is established (see chapter 18).

Coal mines and railways are nationalized. Other industries follow (see chapter 15).

Ireland becomes a republic.

Coronation of Elizabeth II

The Clean Air Act is the first law of widespread application to attempt to control pollution (see chapter 3).

The first motorway is opened (see chapter 17).

The twentieth century 29

The twentieth century

By the beginning of this century. Britain was no longer the world's richest country. Perhaps this caused Victorian confidence in gradual reform to weaken. Whatever the reason, the first twenty years of the century were a period of extremism in Britain. The Suffragettes, women demanding the right to vote, were prepared both to damage property and to die for their beliefs; the problem of Ulster in the north of Ireland led to a situation in which some sections of the army appeared ready to disobey the government; and the government's introduction of new types and levels of taxation was opposed so absolutely by the House of Lords that even Parliament, the foundation of the political system, seemed to have an uncertain future in its traditional form. But by the end of the First World War, two of these issues had been resolved to most people's satisfaction (the Irish problem remained) and the rather un-British climate of extremism died out.

The significant changes that took place in the twentieth century are dealt with elsewhere in this book. Just one thing should be noted here. It was from the beginning of this century that the urban working class (the majority of the population) finally began to make its voice heard, m Parliament, the Labour party gradually replaced the Liberals (the 'descendants' of the Whigs) as the main opposition to the Conservatives (the 'descendants' of the Tories). In addition, trade unions managed to organize themselves .In 1926, they were powerful enough to hold a General Strike, and from the 193os until the 19805 the Trades Union Congress (see chapter 14) was probably the single most powerful political force outside the institutions of government and Parliament.

The school-leaving age is raised to sixteen.

The 'age of majority' (the age at which somebody legally becomes an adult) is reduced from twenty-one to eighteen.

British troops are sent to Northern Ireland.

Capital punishment is abolished.

1971

Decimal currency is introduced (see chapter ij).

Britain joins the European Economic Community.

Marriage of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer.

Falklands War (see chapter 12)

Privatization of British Telecom. This is

the first time that shares in a nationalized company are sold direct to the public (see chapter 15).

Gulf War (see chapter 12)

Channel tunnel opens.

30 2History

QUESTIONS

1 1066 And All That is the title of a well-known joke history book published before the Second World War which satirizes the way that history was taught in British schools at the time. This typically involved memorizing lots of dates. Why, do you think, did the writers choose this title?

2 In 1986, the BBC released a computer-video package of detailed information about every place in Britain. It took a long time to prepare this package but the decision to publish it in 1986 (and not, for example, 1985 or 1987) was deliberate. What is significant about the date?

3 Which of the famous names in popular British history could be described as 'resistance fighters'?

4 Around the year 1500, about 5 million people used the English language - less than the population of Britain at the time. Today, it is estimated that at least 600 million people use English regularly in everyday life - at least ten times the present population of Britain. Why has the use of English expanded so much in the last 500 years?

5 How would you describe the changing relationship between religion and politics in British history? Are the changes that have taken place similar to those that have occurred in your country?

6 Britain is unusual among European countries in that, for more than 300 years now, there has not been a single revolution or civil war. What reasons can you find in this chapter which might help to explain this stability?

SUGGESTIONS

• Understanding Britain by John Randle (Basil Blackwell, Oxford) is a very readable history of Britain, written with the student in mind.

• The Story of English is a BBC series of nine programmes which is available on video. Episodes 2—4 are largely historical in content and very interesting.

• There is a strong tradition of historical novels in English (set at various times in Britain's history). The writings of Georgette Heyer, Norah Lofts, Jean Plaidy, Rosemary Sutcliffe and Henry and Geoffrey Treece are good examples.

|

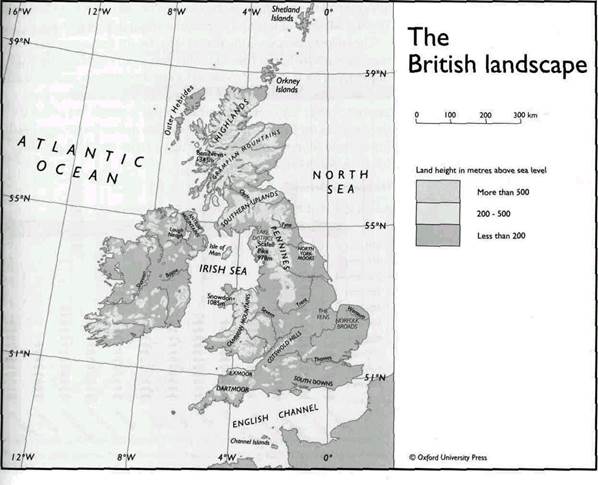

Geography

It has been claimed that the British love of compromise is the result of the country's physical geography. This may or may not be true, but it is certainly true that the land and climate in Britain have a notable lack of extremes. Britain has mountains, but none of them are very high; it also has flat land, but you cannot travel far without encountering hills; it has no really big rivers; it doesn't usually get very cold in the winter or very hot in the summer; it has no active volcanoes, and an earth tremor which does no more than rattle teacups in a few houses is reported in the national news media.

32 3 Geography

Climate

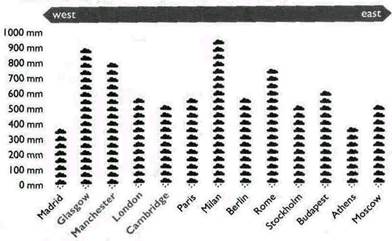

The climate of Britain is more or less the same as that of the northwestern part of the European mainland. The popular belief that it rains all the time in Britain is simply not true. The image of a wet, foggy land was created two thousand years ago by the invading Romans and has been perpetuated in modern times by Hollywood. In fact, London gets no more rain in a year than most other major , European cities, and less than some (o How wet is Britain?).

The amount of rain that falls on a town in Britain depends on where it is. Generally speaking, the further west you go, the more rain you get. The mild winters mean that snow is a regular feature of the higher areas only. Occasionally, a whole winter goes by in lower-lying parts without any snow at all. The winters are in general a bit colder in the east of the country than they are in the west, while in summer, the south is slightly warmer and sunnier than the north.

Why has Britain's climate got such a bad reputation? Perhaps it is for the same reason that British people always seem to be talking about the weather. This is its changeability. There is a saying that Britain doesn't have a climate, it only has weather. It may not rain very much altogether, but you can never be sure of a dry day; there can be cool (even cold) days in July and some quite warm days in January.

The lack of extremes is the reason why, on the few occasions when it gets genuinely hot or freezing cold, the country seems to be totally unprepared for it. A bit of snow and a few days of frost and the trains stop working and the roads are blocked; if the thermometer goes above 8o°F (27°C) (> How hot or cold is Britain?), people behave as if they were in the Sahara and the temperature makes front-page headlines. These things happen so rarely that it is not worth organizing life to be ready for them.

> How wet is Britain?

Annual total rainfall (approximate) in some European cities

Land and settlement 33

| Land and settlement Britain has neither towering mountain ranges, nor impressively large rivers, plains or forests. But this does not mean that its landscape is boring. What it lacks in grandeur it makes up for in variety. The scenery changes noticeably over quite short distances. It has often been remarked that a journey of i oo miles (i 60 kilometres) can, as a result, seem twice as far. Overall, the south and east of the country is comparatively low-lying, consisting of either flat plains or gently rolling hills. Mountainous areas are found only in the north and west, although these regions also have flat areas (l> The British landscape). Human influence has been extensive. The forests that once covered the land have largely disappeared. Britain has a greater proportion of grassland than any other country in Europe except the Republic of Ireland. One distinctive human influence, especially common in southern England, is the enclosure of fields with hedgerows. This feature increases the impression of variety. Although many hedgerows have disappeared in the second half of the twentieth century (farmers have dug them up to increase the size of their fields and become more efficient), there are still enough of them to support a great variety of bird-life. How hot or cold is Britain? Annual temperature range (from hottest month to coldest month) in some European cities |

| > The vanishing coastline Britain is an island under constant attack from the surrounding sea. Every year, little bits of the east coast vanish into the North Sea. Sometimes the land slips away slowly. But at other times it slips away very suddenly. In 1993 a dramatic example of this process occurred near the town of Scarborough in Yorkshire. The Holbeck Hotel, built on a clifftop overlooking the sea, had been the best hotel in town for i i o years. But on the morning of 4 June, guests awoke to find cracks in the walls and the doors stuck. When they looked out of the window, instead of seeing fifteen metres of hotel garden, they saw nothing — except the sea. There was no time to collect their belongings. They had to leave the hotel immediately. During the day various rooms of the hotel started leaning at odd angles and then slipped down the cliff. The Holbeck Hotel's role in the tourism industry was over. However, by 'dying' so dramatically, it provided one last great sight for tourists. Hundreds of them watched the action throughout the day. |

|

|

| Most people in Britain are happier using the Fahrenheit scale of measurement (F). To them, a temperature 'in the upper twenties' means that it is freezing and one 'in the low seventies' will not kill you — it is just pleasantly warm. |

| The Holbeck Hotel falling into the sea |

| The British Isles: where people live |

| 0 50 100km |

| The environment and pollution 35 |

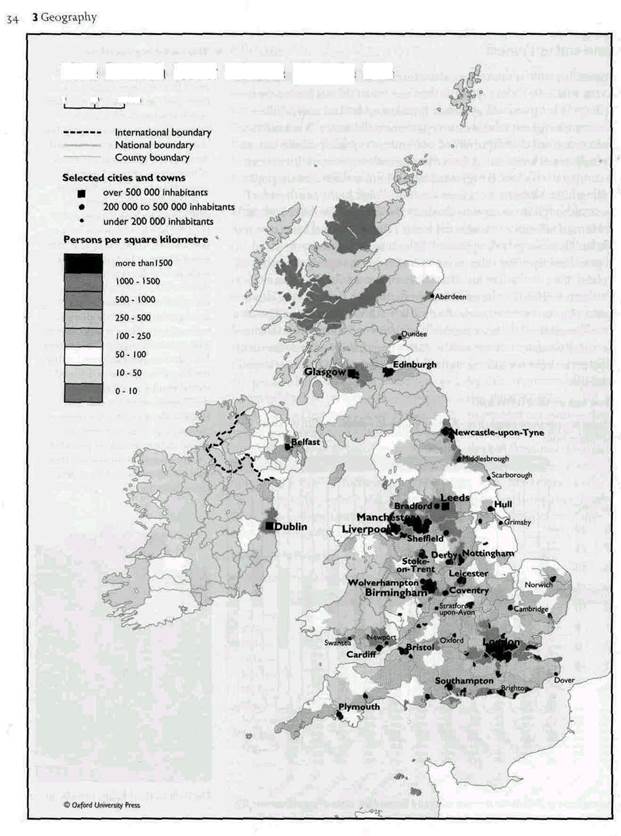

| Much of the land is used for human habitation. This is not just because Britain is densely populated (o The British Isles: where people live). Partly because of their desire for privacy and their love of the countryside (see chapter 5'), the English and the Welsh don't like living in blocks of flats in city centres and the proportion of people who do so is lower than in other European countries. As a result, cities in England and Wales have, wherever possible, been built outwards rather than upwards (although this is not so much the case in Scottish cities). For example, Greater London has about three times the population of greater Athens but it occupies ten times the area of land. However, because most people (about 75%) live in towns or cities rather than in villages or in the countryside, this habit of building outwards does not mean that you see buildings wherever you go in Britain. There are areas of completely open countryside everywhere and some of the mountainous areas remain virtually untouched. The environment and pollution It was in Britain that the word 'smog' was first used (to describe a mixture of smoke and fog). As the world's first industrialized country, its cities were the first to suffer this atmospheric condition. In the nineteenth century London's 'pea-soupers' (thick smogs) became famous through descriptions of them in the works of Charles Dickens and in the Sherlock Holmes stories. The situation in London reached its worst point in 1952. At the end of that year a particularly bad smog, which lasted for several days, was estimated to have caused between 4,000 and 8,000 deaths. Water pollution was also a problem. In the nineteenth century it was once suggested that the Houses of Parliament should be wrapped ; in enormous wet sheets to protect those inside from the awful smell of the River Thames. Until the i96os, the first thing that happened to people who fell into the Thames was that they were rushed to hospital to have their stomachs pumped out! Then, during the 1960s and 1970s, laws were passed which forbade the heating of homes with open coal fires in city areas and which stopped much of the pollution from factories. At one time, a scene of fog in a Hollywood film was all that was necessary to symbolize London. This image is now out of date, and by the end of ' the 1970 it was said to be possible to catch fish in the Thames outside Parliament. However, as in the rest of western Europe, the great increase in 1 the use of the motor car in the last quarter of the twentieth century | caused an increase in a new kind of air pollution. This problem has become so serious that the television weather forecast now regularly issues warnings of 'poor air quality'. On some occasions it is bad enough to prompt official advice that certain people (such as asthma I sufferers) should not even leave their houses, and that nobody should take any vigorous exercise, such as jogging, out of doors. |

| 36 3 Geography |

London

London (the largest city in Europe) dominates Britain. It is home for the headquarters of all government departments, Parliament, the major legal institutions and the monarch. It is the country's business and banking centre and the centre of its transport network. It contains the headquarters of the national television networks and of all the national newspapers. It is about seven times larger than any other city in the country. About a fifth of the total population of the UK lives in the Greater London area.

The original walled city of London was quite small. (It is known colloquially today as 'the square mile'.) It did not contain Parliament or the royal court, since this would have interfered with the autonomy of the merchants and traders who lived and worked there. It was in Westminster, another 'city' outside London's walls, that these national institutions met. Today, both 'cities' are just two areas of central London. The square mile is home to the country's main financial organizations, the territory of the stereotypical English 'city gent'. During the daytime, nearly a million people work there, but less than 8,000 people actually live there.

Two other well-known areas of London are the West End and the East End. The former is known for its many theatres, cinemas and expensive shops. The latter is known as the poorer residential area of central London. It is the home of the Cockney (see chapter 4) and in the twentieth century large numbers of immigrants settled there.

There are many other parts of central London which have their own distinctive characters, and central London itself makes up only a very small part of Greater London. In common with many other European cities, the population in the central area has decreased in the second half of the twentieth century. The majority of 'Londoners' live in its suburbs, millions of them travelling into the centre each day to work. These suburbs cover a vast area of land.

Like many large cities, London is in some ways untypical of the rest of the country in that it is so cosmopolitan. Although all of Britain's cities have some degree of cultural and racial variety, the variety is by far the greatest in London. A survey carried out in the 1980s found that 137 different languages were spoken in the homes of just one district.

In recent years it has been claimed that London is in decline. It is losing its place as one of the world's biggest financial centres and, in comparison with many other western European cities, it looks rather dirty and neglected. Nevertheless, its popularity as a tourist destination is still growing. And it is not only tourists who like visiting London - the readers of Business Traveller magazine often vote it their, favourite city in the world in "which to do business. This popularity is probably the result of its combination of apparently infinite cultural variety and a long history which has left many visible signs of its richness and drama.

Southern England 37

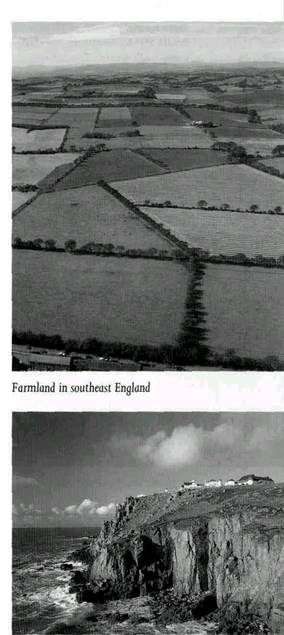

| Southern England The area surrounding the outer suburbs of London has the reputation of being 'commuter land'. This is the most densely populated area in the UK which does not include a large city, and millions of its inhabitants travel into London to work every day. Further out from London the region has more of its own distinctive character. The county of Kent, which you pass through when travelling from Dover or the Channel tunnel to London, is known as 'the garden of England' because of the many kinds of fruit and vegetables grown there. The Downs, a series of hills in a horseshoe shape to the south of London, are used for sheep farming (though not as intensively as they used to be). The southern side of the Downs reaches the sea in many places and forms the white cliffs of the south coast. Many retired people live along this coast. Employment in the south-east of England is mainly in trade, the provision of services and light manufacturing. There is little heavy industry. It has therefore not suffered the slow economic decline of many other parts of England. The region known as 'the West Country' has an attractive image of rural beauty in British people's minds - notice the use of the word 'country' in its name. There is some industry and one large city (Bristol was once Britain's most important port after London), but farming is more widespread than it is in most other regions. Some parts of the west country are well-known for their dairy produce, such as Devonshire cream, and fruit. The south-west peninsula, with its rocky coast, numerous small bays (once noted for smuggling activities) and wild moorlands such as Exmoor and Dartmoor, is the most popular holiday area in Britain. The winters are so mild in some low-lying parts that it is even possible to grow palm trees, and the tdurist industry has coined the phrase 'the English Riviera'. East Anglia, to the north-east of London, is also comparatively rural. It is the only region in Britain where there are large expanses of uniformly flat land. This flatness, together with the comparatively dry climate, has made it the main area in the country for the growing of wheat and other arable crops. Part of this region, the area known as the Fens, has been reclaimed from the sea, and much of it still has a very watery, misty feel to it. The Norfolk Broads, for example, are criss-crossed by hundreds of waterways but there are no towns here, so this is a popular area for boating holidays. The Midlands Birmingham is Britain's second largest city. During the Industrial Revolution (see chapter 2), Birmingham, and the surrounding area of the West Midlands (sometimes known as the Black Country) developed into the country's major engineering centre. Despite the decline of heavy industry in modern times, factories in this area still convert iron and steel into a vast variety of g oods. |

|

| Land's End, the extreme southwest point of England |

38 3 Geography

| >The north-south divide There are many aspects of life in Britain which illustrate the so-called 'north-south divide'. This is a well-known fact of British life, although there is no actual geographical boundary. Basically, the south has almost always been more prosperous than the north, with lower rates of unemployment and more expensive houses. This is especially true of the south-eastern area surrounding London. This area is often referred to as the 'Home Counties'. The word 'home' in this context highlights the importance attached to London and its domination of public life. |

|

| An industrial town in northern England |

| There are other industrial areas in the Midlands, notably the towns between the Black Country and Manchester known as The Potteries (famous for producing china such as that made at the factories of Wedgewood, Spode and Minton), and several towns in the East Midlands, such as Derby, Leicester and Nottingham. On the east coast, Grimsby, although a comparatively small town, is one of Britain's most important fishing ports. Although the midlands do not have many positive associations in the minds of British people, tourism has flourished in 'Shakespeare country' (centred on Stratford-upon-Avon, Shakespeare's birthplace), and Nottingham has successfully capitalized on the legend of Robin Hood (see chapter 2). Northern England The Pennine mountains run up the middle of northern England like a spine. On either side, the large deposits of coal (used to provide power) and iron ore (used to make machinery) enabled these areas to lead the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth century. On the western side, the Manchester area (connected to the port of Liverpool by canal) became, in the nineteenth century, the world's leading producer of cotton goods; on the eastern side, towns such as Bradford and Leeds became the world's leading producers of woollen goods. Many other towns sprang up on both sides of the Pennines at this time, as a result of the growth of certain auxiliary industries and of coal mining. Further south, Sheffield became a centre for the production of steel goods. Further north, around Newcastle, shipbuilding was the major industry. In the minds of British people the prototype of the noisy, dirty factory that symbolizes the Industrial Revolution is found in the industrial north. But the achievements of these new industrial towns also induced a feeling of civic pride in their inhabitants and an energetic realism, epitomized by the cliched saying 'where there's muck there's brass' (wherever there is dirt, there is money to be made). The decline in heavy industry in Europe in the second half of the twentieth century hit the industrial north of England hard. For a long time, the region as a whole has had a level of unemployment significantly above the national average. The towns on either side of the Pennines are flanked by steep slopes on which it is difficult to build and are surrounded by land most of which is unsuitable for any agriculture other than sheep farming. Therefore, the pattern of settlement in the north of England is often different from that in the south. Open and uninhabited countryside is never far away from its cities and towns. The typically industrial and the very rural interlock. The wild, windswept moors which are the setting for Emily Bronte's famous novel Wutherina Heights seem a world away from the smoke and grime of urban life - in fact, they are just up the road (about 15; kilometres) from Bradford! |

| Scotland 39 |

Further away from the main industrial areas, the north of England is sparsely populated. In the north-western corner of the country is the Lake District. The Romantic poets of the nineteenth century, Wordsworth, Coleridge and Southey (the 'Lake Poets'), lived here and wrote about its beauty. It is the favourite destination of people who enjoy walking holidays and the whole area is classified as a National Park (the largest in England).

Scotland

Scotland has three fairly clearly-marked regions. Just north of the border with England are the southern uplands, an area of small towns, quite far apart from each other, whose economy depends to a large extent on sheep farming. Further north, there is the central plain. Finally, there are the highlands, consisting of mountains and deep valleys and including numerous small islands off the west coast. This area of spectacular natural beauty occupies the same land area as southern England but fewer than a million people live there. Tourism is important in the local economy, and so is the production of whisky.

It is in the central plain and the strip of east coast extending northwards from it that more than 80% of the population of Scotland lives. In recent times, this region has had many of the same difficulties as the industrial north of England, although the North Sea oil industry has helped to keep unemployment down.

Scotland's two major cities have very different reputations. Glasgow is the third largest city in Britain. It is associated with heavy industry and some of the worst housing conditions in Britain (the district called the Gorbals, although now rebuilt, was famous in this respect). However, this image is one-sided. Glasgow has a strong artistic heritage. A hundred years ago the work of the Glasgow School (led by Mackintosh) put the city at the forefront of European design and architecture. In 1990, it was the European City of Culture. Over the centuries, Glasgow has received many immigrants from Ireland and in some ways it reflects the divisions in the community that exist in Northern Ireland (see chapter 4). For / example, of its two rival football teams, one is Catholic (Celtic) and the other is Protestant (Rangers).

Edinburgh, which is half the size of Glasgow, has a comparatively middle-class image (although class differences between the two cities are not really very great). It is the capital of Scotland and is associated with scholarship, the law and administration. This reputation, together with its many fine historic buildings, and also perhaps its topography (there is a rock in the middle of the city on which stands the castle) has led to its being called 'the Athens of the north'. The annual Edinburgh Festival of the arts is internationally famous (see chapter 22).

40 3 Geography

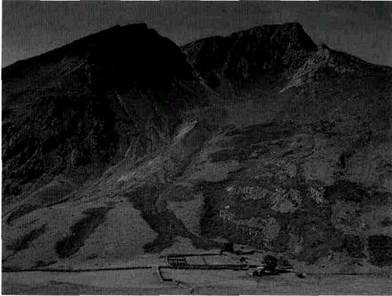

| Part of Snowdonia National Park |

Wales

As in Scotland, most people in Wales live in one small part of it. In the Welsh case, it is the south-east of the country that is most heavily

populated. Coal has been mined in many parts of Britain, but just as British people would locate the prototype factory of the industrial revolution in the north of England, so they would locate its prototype coal mine in south Wales. Despite its industry, no really large cities have grown up in this area (Cardiff, the capital of Wales, has a population of about a quarter of a million). It is the only part of Britain with a high proportion of industrial villages. Coal mining in south Wales has now ceased and, as elsewhere, the transition to other forms of employment has been slow and painful.

Most of the rest of Wales is mountainous. Because of this, communication between south and north is very difficult. As a result, each part of Wales has closer contact with its neighbouring part of England than it does with other parts of Wales: the north with Liverpool, and mid-Wales with the English west midlands. The area around Mount Snowdon in the north-west of the country is very beautiful and is the largest National Park in Britain.

Northern Ireland

With the exception of Belfast, which is famous for the manufacture of linen (and which is still a shipbuilding city), this region is, like the rest of Ireland, largely agricultural. It has several areas of spectacular natural beauty. One of these is the Giant's Causeway on its north coast, so-called because the rocks in the area form what look like enormous stepping stones.

Date: 2015-12-18; view: 2935

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Caledonia, Cambria and Hibemia 2 page | | | Caledonia, Cambria and Hibemia 4 page |