CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Part XI: Major Differences between American and British variants of the English Language

A well-known joke defines Britain and America as two countries divided by a common tongue. Oscar Wilde wrote, “We have really everything in common with America nowadays except, of course, language” (1882, p. 2). There are several approaches to the problem of the relationship between British English and American English. Some scholars treat British and American English as two different languages (Mencken, 1921). Others say that American English is but a dialect of the mother tongue.

A more realistic approach posits American English (AE) as an equal partner with British English (BE). AE and BE are varieties rather than two different languages. Actually, the languages spoken in Britain and America have too much in common to be treated as different languages. Their grammar is basically the same. The main part of the lexicon is essentially the same. Historically, the period of their separate development is too short for them to become absolutely independent. On the other hand, during this period which is not nearly four centuries, the two nations have been living their separate lives which differ in many aspects: different environments, different political systems, different realities of their everyday life, different contacts with other languages, and so on. All this could not but influence the development of their respective language. It is only natural that innovations mainly influence vocabulary, which is always the most flexible and the most changeable part of any language.

Albert Baugh and Thomas Cable believe that the American variant of the English language is an archaic form of British English. They observe that American pronunciation is a somewhat old-fashioned British English pronunciation. It may be true because the Middle English pronunciation of [hw] is still present in American English (AE). It is obvious how the Americans pronounce Whitman as [′hwitmǝn] (as it was pronounced during the Middle English period), not [′witmǝn] (as it is pronounced in BE). Baugh and Cable insist that AE has “qualities that were characteristic of English speech in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries” (1978, p.351), noting that the preservation of the sound [r] in AE and flat [æ] in fast, path, bath, class, and others were abandoned in “southern England at the end of the eighteenth century” (p.351). The pronunciation of AE either [′i¶ǝ] and neither[n′i¶ǝ] was replaced by the diphthong [ai] in BE [′ai¶ǝ] and [′nai¶ǝ], but AE still retains [i]. The use of gotten is a trace of Old English.

In Middle English a great change affected the system of verb conjugation. The difference among the endings of the infinitive –an, the Past tense forms in plural –on, and the Past Participle –en disappeared, and all the endings acquired –en, but by the fourteenth century, the ending –n fell off; however, in AE gotten retained its ending in Past Participle. BE itself retained –en in Past Participle of write (written), beget (begotten), bid (bidden), bite (bitten), choose (chosen), and other irregular verbs. The Americans still use mad in the sense of angry, as Shakespeare and his contemporaries did. Fall is also a BE archaic word for a season. It was recorded in 1545 and is short for leaf-fall. Autumn (slang) in BE meant a hanging through a drop door. Later autumn replaced fall for a season in BE, but AE retained this old-fashioned word fall. The origin of the American I guess goes back to Chaucer period and was still used in the seventeenth century. In general, it is worth noting that AE “preserved certain older features of the language which have disappeared from Standard English in England” (1978, p.353).

Some scholars believe that after the Revolution, the idea of creating the American language, or Americanism, emerged. The word Americanism was coined by President Witherspoon of Princeton. He wrote in 1784, Works, IV, 460, “The word Americanism, which I have coined for the purpose, is exactly similar in its formation and signification to the word Scottish” (as cited in Krapp, 1925, 1966, p.72). The term was created for the “use of phrases and terms, or construction of sentences, even among persons of rank and education, different from the use of the same terms or phrases, or the construction of similar sentences, in Great Britain” (p. 72). The new nation needed a new vocabulary. Thomas Jefferson wrote, “Here [in America] when all is new, no innovation is feared which offers good…. And should the language of England continue stationary, we shall probably enlarge our employment of it, until its new character may separate it in name, as well as in power, from the mother tongue” (as cited in Krapp, 1925, 1966, p.74). Jefferson was right. With the innovations taking place in America, new words were born, and not only the British but also other nations have gone on to borrow these words from America. The influence of American technology, movies, and television on the British vocabulary is immense. However, the influence of British and other countries’ films and television should not be discounted, either.

9.1 Differences in Vocabulary between American and British English

In the sphere of word-building, the difference between British and American English lies in the intensity of the process. American English is more open to neologisms. Among the most productive ways of word-formation one must mention conversion. Nouns are easily formed from verbs: frame-up (n) from frame up (v), verbs from nouns: bus (v) from bus (n), nouns from adjectives: husky (n) from husky (adj), and so on. Back-formation is also very productive: edit (v) is formed from editor (n), laze (v) from lazy (adj), commute (v) from commuter (n), fax (v) from fax (n), and so on. All kinds of shortenings and portmanteau words are very popular with Americans: ad (advertisement), copter (helicopter), motel (motor + hotel), and auditoria (auditorium + cafeteria).

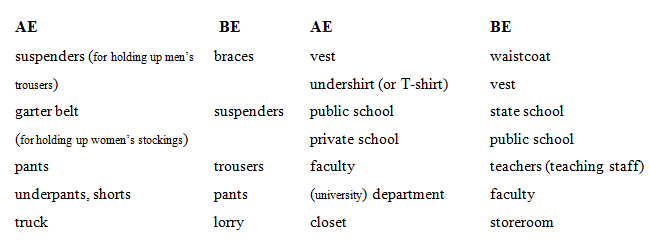

The distance in which BE and AE have traveled in their separation can be measured by vocabulary. There are several differentiations of vocabulary in AE and BE: common ideas expressed by different words, the same words having different meanings, and words expressing reality with no counterparts in the other variant. Since the American legal system is based on the English legal system, the legal terms are similar, e.g., jury, juvenile and justice of peace. However, the definitions of these terms are slightly different. Common ideas expressed by different words and the same words having different meanings are closely connected and produce inconvenience in understanding AE and BE. This part of the word-stock provides the material for common confusion and popular jokes. British cars run on petrol, whereas American cars run on gas(oline). In America, one rents a car, but in Britain, one hires a car. In an American high school, students graduate. In a British school, a pupil (never a student) leaves school. The Americans put coal on a grate, while the British use coals for the same reason. In BE and AE the same words may have different meanings. British chips are American French fries; however, American chips are British crisps. In America an employer hires an employee, but in Britain, one hires a car.

The third type of the word-stock is based on the pioneers and later immigrants from different countries, and they all brought or bring a new vocabulary with them: trapper, frontiersman, pitcher, rum, sequoia, canyon, guacamole, pico de gallo, and others.

Crystal contends that in the lexicon of BE and AE, there are three distinctions which have to be made: some words are found only in AE; some are found only in BE, and some came from either source, thus establishing World Standard English (WSE) (p. 308). He points out that the remaining words represent different kinds of semantic contrast in AE and BE. His classification of semantic contrast is based on M. Benson, E. Benson, and R. Ilson’s (1986b) categories:

· Some words reflect cultural differences but are not a part of World Standard English (WSE): AE Ivy League, Groundhog, revenue sharing and BE A-levels, giro, VAT, and others.

· Some words have a single sense, and they have synonyms in the other variety: BE current account and AE checking account.

· Some words have one meaning in WSE and one or more additional meanings which are specific to BE or AE: caravan (a group of travelers) is common to both BE and AE, but only BE has an additional meaning a vehicle towed by a car, whereas AE uses in this sense the word trailer.

· Some words have one meaning in WSE and a synonym in one or both AE and BE, e.g., both have pharmacy, but AE has drugstore, and BE has chemist’s.

· Some words have no WSE meaning but have different meanings in BE and AE: AE flyover = BE flypast; however, BE flyover = AE overpass.

· Some words are used in AE and BE, but in one of them they are more common, e.g., flat is more common in BE, but apartment is used more often in AE. Other examples are post (BE) vs. mail (AE) and shop (BE) vs. (AE) store (Crystal, p.308).

As we commented earlier, the difference between American and British vocabulary is lessened because many American words made their way into British use, and their number is increasing. Some words, such as advocate, placate, and antagonize, had to overcome a long opposition during most of the nineteenth century. The American traveling to Great Britain and the Englishman traveling to America are amused by differences, but they are not puzzled, because these words are still recognizable. The BE word for railroad is railway, the engineer is a driver, and the conductor is a guard. The baggage car is a van, and the baggage carried is luggage. Regarding the automobile, the English speak of a lorry (AE truck), windscreen (AE windshield), bonnet (AE hood), sparking plugs (AE spark plugs), gear lever (AE gearshift), gearbox (AE transmission), dynamo (AE generator), silencer (AE muffler), boot (AE trunk), and petrol (AE gasoline or gas) (Baugh & Cable, 1978, p. 387).

Such differences can be found in every part of the vocabulary: BE ironmongery = AE hardware, BE lift = AE elevator, BE post = AE mail, BE underground = AE subway, and others. Baugh and Cable observe that some words have a deceptive nature. BE lumber is AE timber, but in BE timber is discarded furniture. A lobbyist in England is a parliamentary reporter, while in America he or she is the one who attempts to influence legislation. A pressman is a reporter in England, while in America the word means the one who works in the pressroom where a newspaper is printed (Baugh & Cable, p. 387). The American sidewalk is an old British word which was cited in the New English Dictionary (1739). However, this word has fallen out of favor in BE and has become a common word in America. The British replaced it with footway or pavement.

American English is rich in fantastically coined or combined words. Two examples are bodacious (blend of bold and audacious) and slantindicular (blend of slanting and perpendicular). Some other Americanisms are bogus, cantankerous, catawampus, cohogle, and rambunctious, to name a few.

The difference in the two nations’ vocabularies is very difficult to trace because a great number of Americanisms are borrowed into British English, so they lose their specific American character. Nevertheless, as the examples above show, a considerable number of words betray a speaker’s nationality. For example, if a British girl and an American girl were out shopping together, the British girl, pointing to a shop window, might say, “I’d like to go into that shop and look at that frock,” while her American friend would more likely say, “I’d like to go into that store and look at that dress.”

9.2 Spelling Differences between American and British English

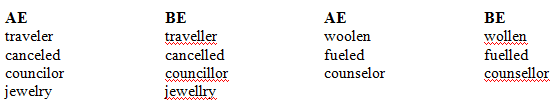

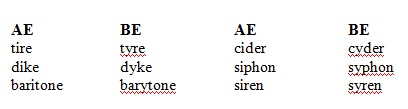

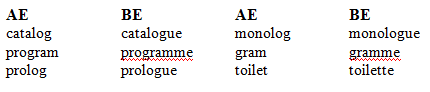

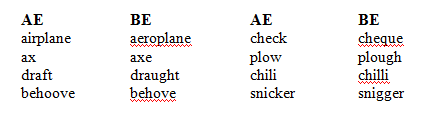

The most significant spelling differences which can be detected in AE and BE can be classified as follows:

American –or versus British –our

American –z versus British –s

American –er versus British –re

American –l versus British –ll

American –ense versus British –ence

The change of y into a, ia or i:

The omission of unaccented foreign terminations

Simplification of ae and oe

Miscellaneous spelling differences

7.3 Grammatical Differences between American and British English

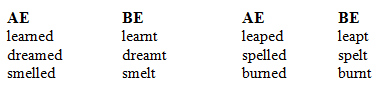

The grammatical systems of languages are more or less stable. Still, close contacts with some other languages often bring about certain simplifications of grammar, which is exactly the case with American English. In the morphological system there are a number of verbs usually treated as regular in American English and as irregular in British English, e.g.:

The following verbs have retained the archaic forms of the past participle in both AE and BE: proven, written, ridden, risen, driven, frozen, spoken, stolen, woven, broken, forgotten, bitten, hidden, eaten, chosen, given, shaken, taken, fallen, swollen, and others. Only AE retained –en in gotten.

While speaking about verb forms, it is necessary to mention the preference of the auxiliary verbs will and would in AE to shall and should in BE: I shan’t go. We shall not leave. I won’t go. We will not leave. The Americans sometimes use past simple where the British use the present perfect: I just wrote vs. I have just written.

Crystal mentions differences of word order in the noun phrases: Hudson River (AE) vs. River Thames (BE), a half hour (AE) vs. half an hour (BE). There is a difference in the use of articles as well: in the future (AE) vs. in future (BE), in the hospital (AE) vs. in hospital (BE), and others (p.311).

One of the most striking grammatical differences is the usage of prepositions. The British live in a street and American live on a street. The English would say, “The university was named after him,” or “He is nervous of doing something,” while the Americans would say, “The university was named for him,” or “He is nervous about doing something.” Here are some more examples:

| AE membership in chat with under the circumstances a week from Tuesday to protest war on the street | BE membership of chat to in the circumstances a week on Tuesday to protest against the war in the street | AE mad about on the weekend out the window on the firing line a new lease on life | BE mad on at the weekend out of the window in the firing line a new lease of life |

There are also different prepositional constructions in British and American English:

| AE to check something | BE To check up on something | AE to visit with someone | BE to call on someone |

BE requires on before a day of the week or a specific date, but AE (especially colloquial) frequently does without it:

| AE The school year begins September 1st. Let’s do it Sunday. | BE The school year begins on September 1st. Let’s do it on Sunday. |

Generally speaking, Americans tend to omit prepositions where the British carefully insert them:

| AE I work nights as a bartender. Is Mary home? | BE I work at nights as a barman. Is Mary at home? |

This tendency to simplify grammatical constructions can be illustrated by different forms of grammatical tenses and moods:

(BE) Have you (got) a pencil? (AE) Do you have a pencil?

In BE, Do you have…? means “Do you habitually have…?” while Have you (got)…? has the meaning “Do you own or possess it at this moment?”

–Have you (got) strawberries? --No, unfortunately not.

--Do you have them? --Yes, usually in the morning.

Subjunctive Mood

The construction They suggested that Brown be dropped from the team is chiefly American English, while They suggested that Brown should be dropped from the team is preferred by British English. AE uses the infinitive with the particle to, while BE uses the construction should + infinitive:

| AE He said to go with him. | BE He said that I should go with him. |

Past Participle seems to be much more popular in the U.S. than it is in England.

AE BE

he lay sprawled he lay sprawling

Many verbs become transitive in AE that are intransitive in BE, e.g.:

| AE to protest something to battle something | BE to protest against something to battle against something |

The examples above are but a few grammatical differences between British and American English.

To sum up, there are significant differences between British and American English. Yet, they do not split these two variants into entirely different languages. Faster communication in the future is likely to override language changes so that the current tendency for American and British English to converge is likely to continue. This does not mean that American and British English will ever become indistinguishable, but they are not likely to become mutually unintelligible, either. In the meantime, as Robert Burchfield, the editor of the Supplement to the Oxford English Dictionary, emphasizes, “American English is and will continue to be the major global form of English into the indefinite future” (1986).

Date: 2015-12-18; view: 2256

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Part VIII: Word Groups and Phraseological Units | | | Part X: Lexicography |