CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

How one family changed art history

Discovering Matisse and Picasso

Americans in Paris

How one family changed art history

·

A walk on the wild side

A walk on the wild side

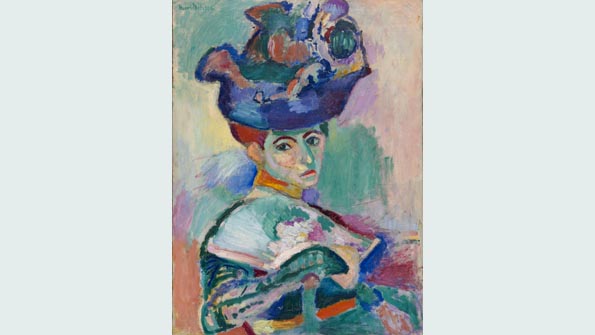

BRIGHT orange hair peeps out from under a woman's navy-blue hat, its brim casting an emerald-green shadow on her brow. When this portrait of his wife by Henri Matisse was shown in a contemporary-art salon in Paris just after it was completed in 1905 people jeered. Leo Stein, an American artist-in-training who was living in the city at the time, called it “the nastiest smear of paint”.

Yet he kept returning to it, often with his younger sister and flatmate, Gertrude. Five weeks later it became his first avant-garde purchase. Now “Woman with a Hat” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the final incarnation of a travelling show that has already been to Paris and San Francisco. All but a handful of the 113 works by Matisse and Picasso were bought by Leo, Gertrude or their older brother Michael and his wife Sarah, who lived not far away.

“The Steins Collect” focuses on the lives and acquisitions of these remarkably prescient buyers. Photographs from the time document the staggering abundance of treasures that hung in their flats. In Leo's small studio, Picasso's tender, haunting “Boy Leading a Horse” (pictured) and “Girl with a Basket of Flowers” soon joined the Matisse portrait and the even bolder “Blue Nude”. Both artists were visitors. The younger Picasso, goaded by Matisse's innovations, raced to catch up with the French artist and overtake him.

The exhibition spotlights each Stein in turn. It opens with Leo, goes on to dreamy but pragmatic Sarah and Michael and ends with the ambitious, self-publicising, trail- blazing modernist writer, Gertrude. Even those who have never read her work recognise her famous sentence, “A rose is a rose is a rose.” The first room is hung with art that influenced Leo when he moved to Paris in 1903. Eight subsequent galleries show how the collection changed.

When Leo and Gertrude were joined by Gertrude's lover Alice B. Toklas in 1910 the collection continued to grow, but then shrank dramatically four years later when Leo decamped for Italy and their art was divided. “Woman with a Hat” was among the many works that stayed with Gertrude. She eventually passed it to Michael and Sarah, who developed a particular passion for Matisse. They owned scores of his works and Sarah became his most ardent supporter. Gertrude, by contrast, championed Picasso. When he painted her portrait, their friendship deepened. That monumental sculpture in paint became the image by which she wanted to be remembered. On her death in 1946 she left it to the Met.

The Steins had private incomes, but they were not hugely rich. “You can either buy clothes or buy pictures,” Gertrude instructed the young Ernest Hemingway. When they started collecting, works by Matisse and Picasso cost little. Leo spoke eloquently about these geniuses when visitors came to their Saturday evening salons. The curious became fans. The family promoted the artists so successfully, that they were soon priced out of the market. Their collections are of early works; as this show proves so well, they chart genius coming into flower.

“More than any exhibition in my 22 years at the Metropolitan, this one is a chameleon,” says Rebecca Rabinow, the Metropolitan's curator for “The Steins Collect”. In San Francisco it focused on the family's social and business activities there. In Paris the emphasis was on Gertrude, who lived there until her death. In New York, its last stop, Leo is the man. He had the eye and the courage to act on it.

Gertrude's writings are rarely read today. But Leo's acquisitions look more and more farsighted. It was he who led his family on the journey that changed the course of modern art. “The Steins Collect” shows how this happened.

·

·

The Steins in the courtyard of 27 rue de Fleurus, from left: Leo Stein, Allan Stein,

Date: 2015-12-17; view: 1256

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Vital Signs: One Problem, Many Faces | | | Oligopoly Literature |