CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

WHAT ARE METEORITES?

by Geoffrey Notkin

What are Meteors? Every year hundreds of hopeful people contact me because they believe that an unusual or out-of-place rock they have found is a meteorite. I frequently receive emails which contain an amusing but impossible statement along the lines of: "I think I've found a meteor." In order to appreciate the humor inherent in this sentence we must first understand the difference between meteors and meteorites. Meteor is the scientific name for a shooting star: the light emitted as fragments—usually rather small—of cosmic material which we sometimes see at night, burning high up in the earth's atmosphere. The bright, and typically very short-lived flame, is caused by atmospheric pressure and friction as pieces of extraterrestrial material become so hot they literally incandesce, as does the air around them. Manned spacecraft such as NASA's space shuttle and the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo capsules experienced similar heating during re-entry into our atmosphere, which is why they employ heat shields to protect the astronauts and cargoes inside.

Meteor Showers There are a number of periodic meteor showers visible each year in the night sky: the Perseids in August, and the Leonids in November usually being the most interesting to observe. The annual meteor showers are the result of our planet passing through debris trails left by comets. The meteors we see during those annual displays are typically small pieces of ice which rapidly burn up in the atmosphere and never make it to the surface of our planet.

Sporadic Meteors An sporadic is a meteor which is not associated with one of the periodic showers and the majority of those meteors also burn up entirely in the atmosphere which acts as a shield, protecting us earthbound humans from falling space debris. Any portion of a meteor which does survive its fiery flight and falls to the surface of the earth is called a meteorite. So, meteorite scientists and hunters understandably chuckle to themselves when a hopeful person claims to have discovered a meteor. The excited people who ask me to help them identify a strange rock should actually be saying: "I think I've found a meteorite." A polite and charming lady once telephoned the Aerolite Meteorites office and asked if we had, for sale, any meteorites from the constellation of Castor and Pollux. I explained to her that most—or possibly all—meteorites found on earth originate from within the Asteroid Belt between Mars and Jupiter, but there is a chance that some meteorites come to us from farther afield. It has been theorized that rare carbon-bearing meteorites known as a carbonaceous chondrites—such as Murchison which fell in Victoria, Australia in 1969—may be the remnants of a comet nucleus, but that remains conjecture. The stone meteorite Zag, which was seen to fall in the Western Sahara in 1998 and later recovered by nomads, contains water and so a slightly more fanciful but intriguing theory developed which suggests that large meteorites may have carried both water and amino acids (the so-called "building blocks of life") to our planet in the distant past.

What are Meteorites?

Meteorites are rocks, usually containing a great deal of extraterrestrial iron, which were once part of planets or large asteroids. These celestial bodies broke up, or perhaps never fully formed, millions or even billions of years ago. Fragments from these long-dead alien worlds wandered in the coldness of space for great periods of time before crossing paths with our own planet. Their tremendous terminal velocity, which can result in an encounter with our atmosphere at a staggering 17,000 miles per hour, produces a short fiery life as a meteor. Most meteors burn for only a few seconds, and that brief period of heat is part of what makes meteorites so very unique and fascinating. Fierce temperatures cause surfaces to literally melt and flow, creating remarkable features which are entirely unique to meteorites, such as regmaglypts ("thumbprints"), fusion crust, orientation, contraction cracks, and rollover lips. These colorful terms will be discussed and examined in future editions of Meteorwritings.

Meteorites: Very Rare and Very Old Meteorites are among the rarest materials found on earth and are also the oldest things any human has ever touched. Chondrules—small, colorful, grain-like spheres about the size of a pin head—are found in the most common type of stone meteorite, and give that class its name: the chondrites. Chondrules are believed to have formed in the solar nebula disk, even before the planets which now inhabit our solar system. Our own planet was probably once made up of chondritic material, but geologic processes have obliterated all traces of the ancient chondrules. The only way we can study these 4.6 billion year old mementoes from the early days of the Solar System is by looking at meteorites. And so meteorites become valuable to scientists as they are nothing less than history, chemistry, and geology lessons from space.

Gemstones from Space Some meteorites even contain gemstones. The beautiful Brenham pallasite, found in Kiowa County, Kansas is packed with sea-green olivine crystals, which is also known as the semi-precious gemstone peridot. Both the Allende meteorite which fell in Chihuahua, Mexico, and the Canyon Diablo iron which formed Arizona's immense and erroneously named Meteor Crater (craters are formed by large meteorites, not meteors) contain micro diamonds. The rarity of meteorites, along with the fact that they are the only way in which most of us will ever have the chance to touch a piece of an alien world, make them of great interest to an ever-expanding network of private meteorite collectors. Meteorite collecting is an exciting and growing hobby and there are perhaps a thousand active enthusiasts in the world today. The international space rock market is something else we will explore in the months ahead.

Geoff Notkin's Meteorite Book

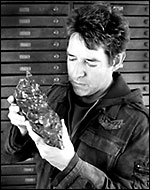

Geoffery Notkin, co-host of the Meteorite Men television series and author of Meteorwritings on geology.com has written an illustrated guide to recovering, identifying and understanding meteorites. Meteorite Hunting: How to Find Treasure From Space is a 6" x 9" paper back with 83 pages of information and photos.

About the Author

|

Date: 2014-12-29; view: 1570

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| History of Geology and Timeline of Geology | | | The Sliding Rocks of Racetrack Playa |