CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Ritual and Religion in the Neolithic

Julian Thomas

School of Arts, Histories and Cultures

University of Manchester

Introduction: A fear of gods?

The archaeological record of the Neolithic period in Europe potentially provides rich raw material for the student of prehistoric ritual and religion. This includes megalithic tombs associated with protracted funerary practices, complex artefacts which imply symbolic significance, ceremonial monuments which could enclose groups of participants, and ambiguous, highly formalised types of visual expression such as figurines and megalithic art. Accordingly, the Neolithic has provided a focus for debates on the archaeology of ritual in recent years (e.g. Barrett 1991; Bradley 2005; Shanks and Tilley 1982; Thomas 2004, inter alia). Yet as Timothy Insoll has pointed out, the same period has seen a surprising reluctance on the part of archaeologists to explicitly address questions of religion (Insoll 2004a: 1; 2004b: 77). Insoll suggests a number of reasons why this might be the case: the embedding of archaeologists within a secular contemporary culture; concerns over the generality of the term ‘religion’; the evanescence of religious meanings. In this contribution, I will attempt to explain the decline of debate on Neolithic religion, and suggest ways in which the field might be revitalised, before turning to the question of ritual through a specific example.

Insoll (2004a: 2) expresses some reservations over any rigid distinction between world religions and ‘traditional’ or ‘primal’ religion, noting that it is possible for the categories to overlap or coincide. Yet it is clear that this division lies behind some of the concerns that have been raised over the investigation of prehistoric religion. Consider, for instance, John Barrett’s criticism of the notion that megalithic tombs were the temples of a unified, pan-European cult (1994: 50). Barrett specifically calls into question Stuart Piggott’s comparison between the architecture of the West Kennet long barrow (Fig. 1) and that of medieval parish churches (Piggott 1962: 61). Piggott’s analogy, says Barrett, relates to a ‘religion of the book’ and its liturgy, so that the spatial organisation of the church is to some extent prescribed by a pre-existing text. ‘There never was a single body of beliefs which characterised ‘Neolithic religion’’, he contends (Barrett 1994: 50). Megalithic tombs reveal a wide range of different practices, which cannot be reduced to a single cultural scheme. Rather, there are broad elements of shared symbolism, deployed in entirely different ways within separate local traditions.

World religions, such as Christianity, Islam and Buddhism, are distinguished by an imperative to proselytise, and consequentially have creeds, scriptures and liturgies that are of potentially universal applicability, and which can be transferred between contexts (Keane 2008: 112). These texts (written or verbal) represent an objectification or distillation of a religious tradition, and are a kind of ‘blueprint’ for religious conduct. Where these texts exist, it may be that an archaeology of scriptural religion is a relatively straightforward task, evaluating the relationship between the text and the archaeological evidence. But in the case of traditional religions, the challenge that presents itself appears to be one of reconstructing religious ideas or beliefs on the basis of material residues. It is arguable that the present generation of archaeologists have intuitively recoiled from such an enterprise, because it implies that abstract ideas precede and underlie acts in the physical world. This perception is manifested in Durkheim’s claim that religious performances ‘are merely the external envelope concealing mental operations’ (quoted by Insoll 2004a: 3). Such a view relies on a Cartesian model of the human being as a corporeal shell concealing an inner world of thought, from within which our actions emanate. Accordingly, archaeologists have drawn a distinction between ritual (which is concerned with practices with tangible outcomes) and religion (which is metaphysical), and elected to concern themselves exclusively with the former.

However, it may be possible to circumvent this problem, and provide a different foundation for an archaeology of Neolithic religious activity. Arguing against the notion of a universal definition of religion, Talal Asad (1993: 29) rejects Clifford Geertz’s view that religion can be understood as a symbolic system that is virtually autonomous from power and practices (see Geertz 1973: 91). For Asad, religion is never a state of mind, but a practical knowledge of institutions and conventions, which amounts to a mode of conduct in the world. As he points out, it is perfectly possible for people to live a religious life without being able to explicitly articulate their religious knowledge (Asad 1993: 36). It is conceivable that some of our difficulties arise from the centrality of belief in Christianity, the religion with which many archaeologists working on the European Neolithic are most familiar. This focus on belief cannot necessarily be extended to all religions, and in any case ‘belief’ can refer to shared, public understandings. In the Christian tradition since St. Augustine the notion that belief is an inner state has formed part of a more general preoccupation with inwardness, in which the route to the deity is found through the contemplation of the inner self (Ruel 1997: 56-9; Taylor 1989: 127).

As Webb Keane has recently argued, it is more helpful to emphasise the primacy of religious acts and phenomena over inner states, and he identifies the former as semiotic forms (Keane 2008: 114). Such forms have a worldly character that renders them open to experience and interpretation, through which understandings are generated. In this sense, beliefs may be ‘parasitic’ upon practices, rather than underlying or generating them. Religious actions and paraphernalia can persist over time and space, and thus be reinterpreted and incorporated into new human projects. Yet, says Keane, although religious phenomena have a tangible quality that allows beliefs to cluster around them, they generally also have the capacity to evoke an ‘ontological divide’. That is, their performance alerts one to the proximity of abnormal or even sacred agencies (ibid: 120). In these terms, the investigation of Neolithic religious activity would cease to be the search for specific deities and spirits, beliefs about the order of the cosmos, or systems of symbols, hidden beneath the surface of the archaeological evidence. Rather, the focus might fall on practices, performances and materials, and the ways in which they functioned to generate and transform understandings of the seen and unseen worlds. In this sense, the rigid separation of religion and ritual begins to narrow somewhat. Yet as we shall see, the study of Neolithic religion to date has been dominated by the conviction that the material evidence is the outward manifestation of beliefs that were widespread and enduring.

The varieties of Neolithic religious experience

As we have already noted, one of the perennial themes in Neolithic archaeology over the past century has been the notion that megalithic tombs were the creation of some form of widely-distributed cult. In much the way that we have just noted, similar ways of treating the dead have been inferred to derive from a shared set of beliefs concerning death and rebirth (Fleming 1969: 297). But beyond this, the idea of ‘megalithic missionaries’ dispersed from the eastern Mediterranean can be attributed to the particular predisposition of culture-historic archaeology to identify sets of artefacts and monuments as the material signatures of distinct groups of people. The gradual development of Gordon Childe’s ideas concerning megalith-builders in Britain are instructive in this context. In The Dawn of European Civilization Childe emphasised the continuity between the British Mesolithic and Neolithic, but argued that megalithic tombs represented an exogenous element, introduced from Mediterranean Europe through coastal trade (1929: 287, 291). However, having collaborated with Stuart Piggott on a study of British Neolithic pottery and its continental affinities, Childe became convinced that the country had been colonized by representatives of the ‘Western Neolithic’ family of cultures, the Windmill Hill people (1931: 41). Childe reasoned that the Western Neolithic cultures were peasant folk who had originated in Africa, perhaps the Nile Delta, and had slowly migrated across Europe (1935: 74). However, megalithic architecture was not a primary feature of Western Neolithic groups. Because Childe saw human beings as fundamentally conservative, he was reluctant to recognise new cultural elements being spontaneously created within prehistoric cultures. As a result, he argued that the megaliths must have had a separate origin, perhaps with the early Minoan tombs of the Aegean. The introduction of an exotic form of mortuary activity from the eastern Mediterranean was most easily explained in terms of religious fanatics who braved the long journey to Britain in order to impose themselves on the Windmill Hill folk as ‘chiefs and wizards’, a ‘spiritual aristocracy’ (Childe 1940: 78; 1957: 326). The architectural variability of Neolithic tombs was consequently attributed to schisms between different elements of the megalithic cult.

What is important to recognise is that Childe’s explanation was a deus ex machina (if the term is not inappropriate in this context). Unable to find a place for megaliths within the cultural repertoire of the Windmill Hill people, he was obliged to identify an alternative origin for them. As culture-history views all human products as the materialisation of the cognitive cultural norms of specific communities, a means had to be devised to account for this extraneous architectural form. Since funerary rites were attributed to religious belief, the incursion of a Mediterranean cult provided an adequate rationalisation. However, Childe resisted the temptation to speculate over the content of the megalithic religion. Yet as Ronald Hutton has elegantly demonstrated, this silence would soon be filled by ideas of a ‘Great Goddess’ that had been developing within Romantic thought during the previous century (Hutton 1997: 92). As Hutton points out, the association of the earth with the female sublime is a thoroughly modern conception, dressed up as a rediscovered primal truth. The various elements of the Goddess theory (a central female deity presiding over a golden age of matriarchy that was eventually destroyed by patriarchal warrior bands from the north) were eventually pulled together by the classicist Jane Ellen Harrison at the start of the twentieth century (ibid: 93).

In Britain, the vision of the Great Goddess was championed by Jacquetta Hawkes during her later career, by when she had elected to write to a more popular audience. In A Land, Hawkes described the worship of the Goddess or Earth Mother as having been brought to Britain from the Mediterranean, and characterises the female deity and her son/lover as the archetypal gods of the ancient world, from which all others were derived (1951: 158). She went on to argue that the scarce chalk figurines from some causewayed enclosures, and the disputed figure from Grimes Graves flint mine, were representation of the ‘White Goddess’. Here, Hawkes was explicitly leaning on Robert Graves’s work of poetic mythology (1948), which draws together themes from Welsh, Irish, Greek and Middle Eastern texts. As with her reliance on Jungian psychology (Hutton 1996: 96) this reveals a willingness to see Neolithic religious practices as having been underpinned by symbols and themes that remained unchanged for millennia, and which relate to fundamental human dispositions. This kind of essentialism was characteristic of its time.

For Hawkes, it was the Great Goddess who presided over the rituals that took place in megalithic tombs, whose swollen mound containing a hidden chamber within which bodies might be crouched in a foetal position betrayed a symbolism of birth and regeneration rather than death and ancestry (Hawkes 1951: 159). She went on to propose that Neolithic society had been matriarchal, and that the lack of representations of warfare and killing attributable to the period demonstrated that the good sense and ‘earthiness’ of the women had restrained the aggressive urges of the men (ibid: 160). Sadly, the growing evidence for village massacres and skeletal trauma indicates that the European Neolithic was no idyllic age of peaceful coexistence (Price, Wahl and Bentley 2006; Schulting and Wysocki 2005; Wahl and König 1987; Wild et. al. 2004). Yet Hawkes proposed that it was the Beaker folk who brought warlike ways of Britain, identifying them as Indo-European ‘high pastoralists, a restless patriarchal society in which the masculine principle had raised the Sky God to pre-eminence’ (Hawkes 1951: 161).

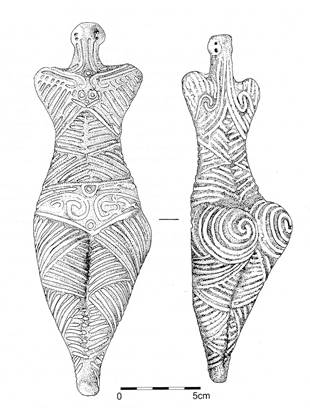

The idea that shared material patterns betrayed shared spiritual beliefs was further developed by O.G.S. Crawford in his The Eye Goddess (1957), in which he proposed that a fertility cult with a female deity had spread from Western Asia to north-west Europe during the Neolithic. The cult’s defining material trait was the motif of the female face or the eye, which degenerated into the spirals and concentric circles of megalithic art. However, the concept of the Neolithic Mother Goddess reached its apogee in the work of Marija Gimbutas (1982; 1989). Gimbutas presented an Old European world-view, which she argued to have been codified in a plethora of symbols, most notably female figurines (1989: xv) (Fig. 2). This religious symbolism had originated in the Palaeolithic, and had not been immediately transformed by the introduction of agriculture to the continent. It related to a mythology of birth, death and the renewal of life, which was central to a society in which women had been clan-heads and queen-priestesses. A single Great Goddess had been venerated throughout the continent, and as in Hawkes’ account had been supplanted by the warrior gods of the Indo-European Kurgan folk (Gimbutas 1989: 321). Like Hawkes and Crawford, Gimbutas tended to conflate material from over a wide geographical area, in the service of a rather grand vision. The cost of this was a degree of insensitivity to the contexts from which figurines were recovered, and the practices in which they may have been engaged (Bailey 2005: 149; Meskell 1995: 75). Despite these failings, Gimbutas continues to have a massive following in the eco-feminist movement, for however flawed her methodology, the image of a peaceful matriarchal past is a deeply attractive one (Meskell 1995: 75). Equally, the notion of a primordial female deity remains a potent one within mainstream Neolithic archaeology, emerging periodically as a default explanation (see Cassen 2000: 242 for comments on the place of the Great Goddess in French archaeology).

The development of processual archaeology in the 1960s and 1970s coincided with a decline in the investigation of Neolithic religion. This is slightly surprising, for while some culture-historic archaeologists had declared matters of belief to be beyond the competence of the discipline (Hawkes 1954), the New Archaeologists had sought to demonstrate that all aspects of culture had an adaptive significance. Thus Binford (1971) had presented mortuary rites as a means by which the loss of a social actor might be communicated to the group as a whole, enabling their roles and statuses to be passed on to others. So it might have been expected that the systemic role of ritual and religion in prehistoric European societies would have been explored by processual archaeologists. Such had been the perceived excesses of the Goddess cultists, however, that the period was largely given over to the debunking of arguments connecting putative prehistoric migrations with Earth-Mother beliefs (e.g. Renfrew 1967: 276). Thus Fleming (1969: 248) offered a detailed evaluation of the evidence for the worship of female deities in the Neolithic of Western Europe, and concluded that the forms of expression represented by statue-menhirs, gallery-graves and other megalithic art were localised and chronologically dispersed (Fig. 3). Rather than a universal Great Goddess, they probably amounted to localised traditions of limited duration. It was only later that the idea of a ‘cognitive processualism’ developed, bringing with it the implication that religious ideas might play a part in the collective adaptation of human communities (Renfrew 1994: 48). Once again, though, this form of archaeology identifies religion with belief, and locates belief inside the human mind.

If much of Neolithic archaeology has sought the root of diverse forms of symbolic behaviour in a uniform and enduring body of religious beliefs, a rather different form of essentialism has emerged in recent years. With various collaborators, David Lewis-Williams has explored the proposition that all religions are attempts to codify and interpret ecstatic experiences, which are the outcome of mental states produced by the brain under unusual conditions (Lewis-Williams and Pearce 2005: 25). Broadly speaking, religions involving the experience and exegesis of such altered states are referred to as ‘shamanism’. The Neolithic involved new ways of understanding these mental states, which were increasingly cast as an esoteric knowledge that was revealed only to a restricted elite. Thus the complicated imagery of megalithic art inside chambered tombs in Brittany and Ireland demonstrates the efforts of emerging elites to control and restrict hallucinatory religious experience (Fig. 4), and to monopolise the revelations that flowed from it (Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1993: 60). Attempting to refine this neuro-psychological model, Jeremy Dronfield produced a classification of the types of imagery associated with a variety of forms of mind-altering practice. He argued that migraine, flickering lights, and the use of hallucinogenic substances might all have been responsible for generating the images that were translated into Irish passage tomb art (Dronfield 1994: 545; 1995: 272). However, Dronfield (1996) went on to emphasise the particular importance of ‘subjective tunnel experiences’ (such as tunnel vision), which were monumentalised in the increasingly lengthy passages of the Irish tombs. These he reasoned to have represented the entrance to an alternative reality experienced within the architecture.

While the neuro-psychologists break radically with some aspects of previous interpretations of Neolithic religious practice, they none the less sustain the view that acts in the physical world are the outcomes of mental states, although in this case chemically-induced rather than transmitted as collective norms. Rather than imagining universal bio-psychological states being passed through some form of cultural filter and contextually rationalised, it might be profitable to consider shamanic practices as both corporeal and social. Drug-taking and the induction of trance states are embodied experiences, often conducted collectively: they are never raw cognitive stimuli over which cultural understanding is draped. While altered states may have formed an element of Neolithic ceremonial activities, they would always have been understood from within established expectations, and sanctioned by social convention. As with the preoccupation with belief as the focal element of prehistoric religion, we would do well to shift our concern toward practice, and its place within the social lives of embodied subjects embedded in cultural traditions.

The archaeology of ritual revisited

We can turn now from religion to ritual, a topic that has been more thoroughly investigated within Neolithic archaeology. We can begin with a paradox: much of the recent archaeological literature expresses a desire to break down the opposition between ritual and the everyday, and yet there are certain kinds of performances, such as funerals and initiations, that we are happy enough to label as ‘rituals’ (Brück 1999: 316). The recent work conducted under the aegis of the Stonehenge Riverside Project at the Late Neolithic henge monument of Durrington Walls in Wiltshire has brought this problem into focus, by revealing evidence for a range of different practices, some of which we might wish to identify as ‘ritual’ or ‘ritualised’ (Parker Pearson et. al. forthcoming) (Fig. 5). Durrington Walls has a significant place in the history of archaeological attempts to grapple with the issue of ritual, and back in 1984 Colin Richards and the author used the material from Geoffrey Wainwright’s excavations of 1966-7 in order to try and establish a method for identifying ritual using the structural qualities of the archaeological evidence (Richards and Thomas 1984; Wainwright and Longworth 1971). Following Maurice Bloch (1974: 58), we argued that ritual represents a formalised and restricted form of communication, sanctioned by tradition, which enables dominant messages to be expressed in ways that are not susceptible to evaluation. Ritual employs archaic forms of speech, rhyme and song, and prescribed bodily postures and patterns of movement in order to convey cardinal truths, which are not to be argued with.

We suggested that the same formality and restriction should be manifested in the use and deposition of material culture, and set out to demonstrate that the spatial variation in pottery decoration, and the representation of stone tools and faunal remains within the Durrington henge was highly patterned, reflecting control, segregation, and ordering in the use of material symbols. Different patterns of deposition and association were suggested for the Northern and Southern timber circles, the midden and platform, and the henge ditch. Over the past twenty years, the debate has moved on, and new excavations have clarified the structural sequence at Durrington Walls. It is now appropriate to reflect on how our views of the practices documented by the internal features within the henge might be affected by these developments.

Recently, a number of authors have drawn attention to the presumed separation of ritual from everyday life in archaeological thought. Richard Bradley (2005: 28), for instance, has noted that domestic activity is often imagined to have been spatially separate from, and to have followed a different logic to, ritual. Similarly, Joanna Brück (1999: 317) identifies the distinction between irrational, non-productive, highly symbolic ritual and practical, functional, technical action with modern western rationality. Ritual, she argues, is perceived as not doing anything, so that it comes to be understood as signifying something else, or at best as functioning ideologically, to mask and misrepresent social reality. Yet in pre-modern contexts, ritual is not separated from the secular. In what Brück refers to as animist or monist systems of thought, there is no distinction between functional and symbolic action. A single practical logic governs all forms of action, and ritual is understood as having tangible outcomes, in terms of curing, divination, or intercession with spirits.

Brück’s argument is that if we persist in distinguishing between ritual and the everyday, we are likely to neglect apparently mundane contexts in which deposition was nonetheless governed by cultural logics quite distinct from our own. She therefore recommends dispensing with the category of ritual altogether. But on the other hand, she recognises in passing the existence of rites of transformation, such as burial and marriage, but she isn’t clear about how these should be dealt with archaeologically (Brück 1999: 329). Now, we can agree with virtually all of Brück’s argument, especially when she advocates above all the investigation of past rationalities, without having to accept her conclusion that we should not talk about ritual at all. Instead, it may be that we should identify ritual not as a separate sphere of practice, but as a distinct mode of conduct, which people move into and out of in the course of their day. An obvious example would be the way in which an industrial worker might break off from their labours, unroll a mat, and pray for a few minutes. The worker’s comportment signals that something has changed, even if he has not entered a consecrated space or made use of sanctified artefacts.

In the contemporary west, ritual may have been set apart from the everyday, but this should perhaps alert us to the very different role and significance that ritual can have in different societies. In modern nation-states, ritual still serves to bring the past to mind, to reinforce social ties, or to sustain minority identities (James 2003: 107). But it is less often understood as having a tangible efficacy, as Brück maintains. The distinction between ritual and mundane action lies not between different logics, but in an intensification or heightening of the experience of one’s immediate situation, including cosmological relations. This is brought about through submitting oneself to a discipline, which draws on tradition and precedent, and establishes distinctive social conditions (Barrett 1991: 4). Revealingly, the Ndembu world for ‘ritual’ also means ‘obligation’ (Turner 1969: 11). Ritual is based on memory, reiterating or quoting past events and utterances, but as a heightening of experience it is itself often highly memorable (Connerton 1989: 44). As Victor Turner pointed out, symbols are the basic elements of ritual, but these symbols may be less concerned with communication than with expression, which is to some degree open to interpretation (Turner 1967: 19). People often know what acts and utterances are required to make ritual efficacious, without actually knowing what they mean (Lewis 1980: 6).

Moreover, although everything in ritual is a symbol, these should not be thought of as arbitrary signifiers, so that ritual becomes an empty code that merely refers to other things. On the contrary, ritual symbols bring powers, connotations, virtues and allusions to bear on a specific location, and render them manipulable. Ritual symbols provide a microcosm that is networked to the macrocosm, offering influence in the world at large through performative engagement. Brück is correct in saying that in pre-modern worlds there may be no distinction between sacred and secular, meaning and function, so that powers and spiritual qualities may be immanent in the world as a whole. None the less, there may be places, occasions and persons that allow privileged access to these powers and qualities, and this is often what ritual provides, in non-western contexts.

Some rituals constitute ceremonial events, distinct from everyday life, or punctuating the seasonal cycle (Van Gennep 1960). But there are also everyday observances, like daily prayer or formalised ways of serving and consuming food. In these circumstances, elements of ritual are not only embedded in mundane activity, but they take on a habitual character which make them unconsidered aspects of personal and group identity. It follows from this that from an archaeological point of view there will be a very fuzzy line around the edge of what we consider to be ritual activity. At one end of the continuum there will be distinctive rites and ceremonies, but we should expect these to shade out into varying degrees of ritualisation, including the unconsidered and the unconscious.

Reconsidering ritual at Durrington Walls

This picture perhaps better expresses the situation now revealed at Durington Walls, where new fieldwork has identified a complex and protracted structural sequence. The different elements of the site that were effectively treated as equivalents in the 1984 analysis are not necessarily contemporary, their character has often been reassessed, and the nature of deposition varies between the repetitive and the episodic. The platform outside the Southern timber circle has been identified as a fragment of a metalled avenue that connects the circle with the River Avon; the ‘midden’ may represent one or more terraced buildings; and much of the feasting activity on the site (see Albarella and Serjeantson 2002) appears to pre-date the construction of the henge bank and ditch, which themselves seem to represent a final statement terminating the complex (Parker Pearson 2007: 129; Parker Pearson et. al. 2007: 631).

At the Southern Circle, what had formerly been designated ‘Circle 1B’ (that is, part of the first-phase structure) is likely to have been integral to the second phase, where the smaller post-holes may have supported shuttering or fencing, creating a secluded inner space within the timber circle (Thomas 2007). Such a space would have been similar in size and character to the space within the sarsen trilithon horseshoe at Stonehenge, now demonstrated to have been roughly contemporary with the Southern Circle (Parker Pearson et. al. 2007: 626). Indeed, the stone settings at Stonehenge and the Southern Circle can now be seen as complementary structures, similar in architectural organisation and forming the two ends of a unified pattern of movement down the River Avon and the two avenues. The first phase of the Southern Circle was thus a simpler structure, very comparable with the Northern Circle. It probably consisted of four central posts, surrounded by a single ring of lesser posts, approached by an avenue and crossed by a façade. The implication of this is that the second phase stands alongside Woodhenge and Stonehenge as examples of an extremely elaborate architecture which built on simpler precedents (Pollard and Robinson 2007: 167).

Following the 1967 excavation at Durrington Walls, Wainwright argued that the Southern Circle had been a massive roofed timber building, and that within this structure offerings of pottery, stone and animal bones had been placed at the feet of the posts supporting the roof (Wainwright with Longworth 1971: 23-38). However, the recognition that the circle was incomplete supports the view that the structure was composed of free-standing posts (Fig. 6). Hence it is unlikely that objects would have survived un-weathered on the surface to be incorporated into the ‘weathering cones’ left behind by the rotting out of the posts. These Wainwright argued to have been created by the eroding-back of the post-packing, creating features that trapped most of the artefacts recovered from the Circle. Excavations in 2005-6 demonstrated that these were actually re-cut pits, dug into the tops of the post-holes after the timbers had rotted out (Thomas 2007: 151). Within these re-cuts, finds formed dense clusters, obviously placed or tipped rather than having fallen haphazardly into the cut. There was often a distinct sequence to the deposition, with spreads of animal bone succeeded by layers of knapping waste, followed by the pacing of individual Grooved Ware sherds.

Importantly, all of this material must have been deposited after the timber circle had fallen into ruin, a point that was barely addressed in the 1984 paper. The placing of these deposits therefore appears to have been commemorative in character, creating an ‘architecture of memory’ which referred to the vanished monument, very probably at the same time as the natural amphitheatre of Durrington Walls was being enclosed by the henge ditch. So, although the re-cutting was a singular event rather than a repetitive practice, it was very explicitly one that drew on and cited the past. Moreover, it is highly significant that the spatial distribution of artefacts in the re-cuts echoed that of the antler picks which had been deposited in the original packing of the post-holes. In both cases, the post-holes around the entrance to the circle were emphasised. The deliberate deposition of the antler picks used to excavate ditches, pits and shafts during the Neolithic is a fine example of a ritualised act that punctuates the cycle of labour and construction. More than a generation later, antlers and posts were cited and brought back to notice through the act of re-cutting. All of these acts are ritual, not just because they were highly structured, but because they betray a mode of conduct in which people were highly attentive to substances and materials, their histories, powers and connotations.

200 metres west from the Southern Circle, a group of at least six penannular structures have been revealed by geophysical survey, arranged around a terrace overlooking the timber circle and the eastern entrance (Thomas 2007: 152). Two of these were investigated in the summer of 2006, and rather than burials or timber circles, they proved to contain buildings similar to those that had been investigated in a Late Neolithic settlement at the eastern entrance of Durrington Walls (Parker Pearson 2007: 133). However, both were contained within timber palisades as well as hengiform ring-ditches. The larger one, in Trench 14, also had a façade of massive posts immediately in front of the building, in close-set pairs which may indicate that they were the wooden equivalent of the Stonehenge trilithons. In other words, these structures combined the characteristic Grooved Ware house form with architectural elements that were associated with timber circles. While the surface had been subject to erosion before a thick layer of colluvium had been laid down, there were no finds at all on the house floors or in the post-holes. A large pit outside Building 14 contained quantities of animal bone and Grooved Ware, giving the impression of the clearing-up operations required to keep the structure clean. This contrasts very markedly with the general filthiness of the eastern entrance houses. Beside the façade posts, another shallow pit contained the butchered remains of two pigs, with numerous articulated bones indicating a rather more prompt burial than the clean-up pit.

While the eastern entrance houses demonstrate ritual acts of various kinds conducted in what was broadly a domestic setting (see Parker Pearson 2007: 138), the Western Enclosures suggest the same kind of building being subject to a very different kind of conduct, as well as being structurally elaborated in order to provide deeply secluded spaces. They may simply have represented elite residences, but the evidence could also be read to indicate that they were shrines, cult-houses, or spirit-lodges (Fig. 7). Overall, the evidence from the internal structures at Durrington Walls does not show that this was a ‘ritual site’, for there is no such thing. There are simply sites at which ritual has taken place, and at Durrington a variety of acts of various degrees of ritualisation, from formal rites to habitual practices, were woven into a complicated history, marking moments of crisis, transformation, and daily routine.

Conclusion

Despite a long history of research, the archaeology of ritual and religion in Neolithic Europe has yet to realise its potential. This chapter has suggested some ways in which the rich evidence available to us can be used to address these issues. The way forward lies with abandoning the attempt to reconstruct past mental states, and recognising that both ritual and religion involved practices enacted in the material world.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Tim Insoll for the invitation to contribute to this volume. Part of the text was delivered at a meeting of the Neolithic Studies Group, and I should like to thank Stuart Needham for organising that event.

References

Asad. T. 1993 Genealogies of Religion. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Albarella, U. and Serjeantson, D. 2002 A passion for pork: meat consumption at the British Late Neolithic site of Durrington Walls. In P. Miracle and N. Milner (eds) Consuming Passions and Patterns of Consumption, 33-49. Cambridge: McDonald Institute.

Bailey, D.W. 2005 Prehistoric Figurines: Representation and Corporeality in the Neolithic. London: Routledge.

Barrett, J.C. 1991 Towards an archaeology of ritual. In: P. Garwood, D. Jennings, R. Skeates and J. Toms (ed.) Sacred and Profane, 1-9. Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology.

Barrett, J.C. 1994 Fragments from Antiquity: An Archaeology of Social Life in Britain, 2900-1200 BC. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bloch, M. 1974 Symbols, song, dance and features of articulation. Archives of European Sociology 15, 55-81.

Bradley, R.J. 2005 Ritual and Domestic Life in Prehistoric Europe. London: Routledge.

Brück, J. 1999 Ritual and rationality: some problems of interpretation in European Archaeology. Journal of European Archaeology 2, 313-44.

Cassen, S. 2000 Stelae reused in the passage graves of Western France: history of research and sexualisation of the carvings. In: A. Ritchie (ed.) Neolithic Orkney in its European Context, 233-46. Cambridge: McDonald Institute.

Childe, V.G. 1925 The Dawn of European Civilisation. London: Kegan Paul.

Childe, V.G. 1931 The continental affinities of British Neolithic pottery. Archaeological Journal 88, 37-66.

Childe, V.G. 1935 The Prehistory of Scotland. London: Kegan Paul.

Childe, V.G. 1940 Prehistoric Communities of the British Isles. London: Chambers.

Childe, V.G. 1957 The Dawn of European Civilisation [6th edition]. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Connerton, P. 1989 How Societies Remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crawford, O.G.S. 1957 The Eye Goddess. London: Phoenix House.

Dronfield, J. 1994 Subjective vision and the source of Irish megalithic art. Antiquity 69, 539-49.

Dronfield, J. 1995 Migraine, light and hallucinogens: the neurocognitive basis of Irish megalithic art. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 14, 261-75.

Dronfield, J. 1996 Entering alternative realities: cognition, art and architecture in Irish passage tombs. Cambridge Journal of Archaeology 6: 7-72.

Fleming, A. 1969 The myth of the mother-goddess. World Archaeology 1, 247-61.

Geertz, C. 1973 Religion as a cultural system. In: C. Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures, 87-125. New York: Basic Books.

Gimbutas, M. 1989 The Language of the Goddess. London: Thames and Hudson.

Graves, R. 1948 The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth. London: Faber and Faber.

Hawkes, C.F.C. 1954 Archaeological theory and method: some suggestions from the Old World. American Anthropologist 56, 155-68.

Hawkes, J. 1951 A Land. London: Cresset Press.

Hutton, R. 1997 The Neolithic great goddess: a study in modern tradition. Antiquity 71, 91-9.

Insoll, T. 2004a Are archaeologists afraid of gods? Some thoughts on archaeology and religion. In: T. Insoll (ed.) Belief in the Past, 1-6. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Insoll, T. 2004b Archaeology, Ritual, Religion. London: Routledge.

James, W. 2003 The Ceremonial Animal: A New Portrait of Anthropology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Keane, W. 2008 The evidence of the senses and the materiality of religion. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute Special Issue 2008, S110-27.

Lewis, G. 1980 Day of Shining Red: An Essay on Understanding Ritual. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. and Dowson, T.A. 1993 On vision and power in the Neolithic: evidence from the decorated monuments. Current Anthropology 34, 55-65.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. and Pearce, D. 2005 Inside the Neolithic Mind. London: Thames and Hudson.

Meskell, L. 1995 Goddesses, Gimbutas and ‘New Age’ archaeology. Antiquity 69, 74-86.

Parker Pearson, M. 2007 The Stonehenge Riverside Project: excavations at the east entrance of Durrington Walls. In: M. Larsson and M. Parker Pearson (eds.) From Stonehenge to the Baltic, 125-44. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports s1692.

Parker Pearson, M., Cleal, R., Marshall, P., Needham, S., Pollard, J., Richards, C., Ruggles, C., Sheridan, A., Thomas, J., Tilley, C., Welham, K., Chamberlain, A., Chenery, C., Evans, J., Knüsel, C., Linford, N., Martin, L., Montgomery, J., Payne, A. and Richards, M. 2007 The age of Stonehenge. Antiquity 81, 617-39.

Parker Pearson, M., Pollard, J., Richards, C., Thomas, J., Tilley, C., and Welham, K. forthcoming The Stonehenge Riverside Project: exploring the Neolithic landscape of Stonehenge. Documenta Praehistorica 35.

Parker Pearson, M. and Ramilsonina 1998 Stonehenge for the ancestors: the stones pass on the message. Antiquity 72, 308-26.

Piggott, S. 1962 The West Kennet Long Barrow: Excavations 1955-56. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Pollard, J. and Robinson, D. 2007 A return to Woodhenge: the results and implications of the 2006 excavations. In: M. Larsson and M. Parker Pearson (eds.) From Stonehenge to the Baltic, 159-68. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports s1692.

Price, T.D., Wahl, J. and Bentley, R.A. 2006 Isotopic evidence for mobility and group organisation amongst Neolithic farmers at Talheim, Germany, 5000 BC. European Journal of Archaeology 9, 259–284.

Renfrew, C. 1967 Colonialism and megalithismus. Antiquity 41, 276-88.

Renfrew, C. 1994 The archaeology of religion. In: C. Renfrew and E. Zubrow (eds.) The Ancient Mind: Elements of Cognitive Archaeology, 47-54. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, C.C. and Thomas, J.S. 1984 Ritual activity and structured deposition in later Neolithic Wessex. In: R. Bradley and J. Gardiner (eds) Neolithic Studies, 189-218. Oxford: BAR.

Ruel, M. 1997 Belief, Ritual and the Securing of Life: Reflexive Essays on Bantu Religion. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Schulting, R. and Wysocki, M. 2005 'in this chambered tumulus were found cleft skulls ...': an assessment of the evidence for cranial trauma in the British Neolithic. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 71, 107-38.

Shanks, M. and Tilley, C.Y. 1982 Ideology, symbolic power and ritual communication: a reinterpretation of Neolithic mortuary practices. In: I. Hodder (ed.) Symbolic and Structural Archaeology, 129-154. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, C. 1989 Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thomas, J.S. 2004 The ritual universe. In: I. Shepherd and G. Barclay (eds.) Scotland in Ancient Europe, 171-8. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

Thomas, J.S. 2007 The internal features at Durrington Walls: investigations in the Southern Circle and western Enclosures, 2005-6. In: M. Larsson and M. Parker Pearson (eds.) From Stonehenge to the Baltic, 145-58. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports s1692.

Turner, V. 1967 The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Turner, V. 1969 The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. New York: Aldine De Gruyter.

Van Gennep, A. 1960 The Rites of Passage. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Wahl, J. and König, H.G. 1987 Anthropologisch-traumatologisch untersuchung der menschlichen skelettreste aus dem Bandkeramischen massgrab bei Talheim, Kreis Heilbronn. Fundberichte Baden-Württemberg 12, 65-193.

Wainwright, G.J. and Longworth, I.H. 1971 Durrington Walls: excavations 1966-1968. London: Society of Antiquaries.

Wild, E.M., Stadler, P., Häusser, A., Kutschera, W., Steier, P., Teschler-Nicola, M., Wahl, J. and Windl, H. 2004 Neolithic massacres: local skirmishes or general war in Europe? Radiocarbon 46, 377-85.

Figures

Fig. 1: The façade of the West Kennet long barrow, north Wiltshire (photo: author).

Fig. 2 Cucuteni figurine from Draguseni (after Bailey 2005).

Fig. 3: La Gran’mére du Chimquiére, statue-menhir from Guernsey (after Shee Twohig 1981).

Fig. 4: Megalithic art at Newgrange, Ireland (photo: author).

Fig. 5: Durrington Walls, Wiltshire; location of excavations 2004-7 (illustration Mark Dover for Stonehenge Riverside Project.

Fig. 6: Reconstruction of the Southern Circle at Durrington Walls, constructed for a Time Team TV programme (photo: author).

Fig. 7: The Western Circles at Durrington Walls (reconstruction image by Aaron Watson).

Date: 2015-12-11; view: 2676

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Suicidal Person Sues Subway Train Authority | | | Down the coast of Africa |