CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

American Revolution and War for Independence

| T |

sports supplement has

been recalled because

of a “new and improved”

ingredient. The company’s

CEO wonders: Why do the

decisions we make keep

coming back to haunt us?

HE COLD JANUARY SKY was just

dawning gray over Minneapolis as Don

Rifkin awoke. With every cell in his

body, he longed to put a pillow over his

head and sleep, but the alarm added in-

sult to injury. Slapping the off button

and pulling on his oversized Turkish

bathrobe, he stole from the bedroom

and quietly shut the door behind him,

leaving his wife to sleep. He padded

toward the kitchen and turned on the

coffeemaker.

Sitting down at the kitchen table, Don

sleepily clicked a few keys on his laptop

and began glancing through his favorite

stock chat. Scanning the list of senders,

he saw a red exclamation point next to

the name Stan with the headline “Bad

news!” When he read the message, Don

gasped:

Did anyone hear that Wally Cum-

mings just resigned from Dipensit?

Turns out he lied on his resume –

never received that PhD from U.C.

Berkeley as he’d claimed! The stock’s

gonna drop fast once this hits the

street.

Don felt slightly queasy. A year ear-

lier, his own company, Nutrorim, had

purchased a small stake in Dipensit.

“Sheesh, I didn’t exactly trust that guy,”

he grumbled.

He recalled how smoothly the whole

decision process had seemed to go when

Laurence Wiseman, the hard-driving

CFO of Nutrorim, had championed the

purchase of the Dipensit stock, insist-

ing that the small company might make

an excellent acquisition candidate in

the future. A subcommittee had been

formed to carefully review the purchase

decision. Don vaguely remembered that

the best-selling performance-enhancing

sports powder on the market.

The following year, when the new ver-

sion of ChargeUp had been in its final

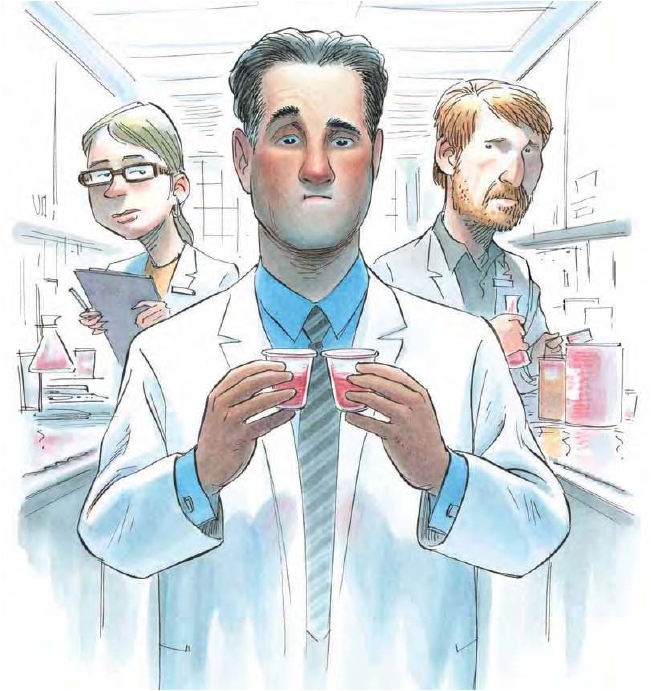

stages of development, Don and R&D

head Steve Ford had dressed in white

coats and walked through the com-

pany’s huge lab, agleam with chrome

and white tile. They wended their way

Wiseman, Ford, and a group of others

tended to form strong opinions and

push them aggressively. And while Don

had his own opinions–and often voiced

them – he also worked hard to keep the

company’s decision-making processes

open and democratic, and made a point

of asking for input from as many people

as possible.

there had been a few murmurs of con-

cern–someone had even questioned the

credentials of Cummings, the start-up’s

CEO. But in the end, the subcommittee

seemed to have addressed the concerns,

and the senior team stood behind the

decision.

Don cinched his bathrobe tighter.

“For decisions with a certain amount of built-in

predictability…the process seems to work really well.

But if a decision involves clear winners and losers,

it stalls.”

During the past year, Nutrorim had suf-

fered from a spate of bad decisions. In

fact, that’s what today’s meeting was

about. A consultant, hired to review the

company’s decision-making processes,

was coming in that morning to present

the results of his individual interviews

with senior managers.

To Everyone’s Taste?

The previous spring, Nutrorim had been

at the top of its game. Founded in 1986

by an organic farmer and his wife, the

company had sold its products through

a network of individual distributors

before Don had joined as CEO in 1989.

Thanks to a series of testimonials of-

fered by doctors and personal trainers,

Nutrorim’s products had gained na-

tional attention. Then, following an en-

dorsement by a famous Olympic ath-

lete, sales of ChargeUp, the company’s

organic, performance-enhancing sup-

plement powder, had gone through the

roof. As a result, Nutrorim had hired

hundreds of new employees, expanded

its production facilities, and acquired

two vitamin firms. After going public in

1997, the company had expanded dis-

tribution of ChargeUp through exclu-

sive deals with nutrition stores and ath-

letic clubs, and by 2002, ChargeUp was

past stainless steel tables where techni-

cians milled seeds and blended the all-

organic ingredients that comprised Nu-

trorim’s various lines of vitamins and

nutritional supplements.

“Hey, Darlene, how are you?” Don

waved at a lab technician who was wear-

ing gloves, a hair bonnet, and a face

mask and pushing a trundle cart down

an aisle. Though she was recognizable

only by the walnut-rimmed glasses she

wore, she smiled –he could tell by the

wrinkles around her eyes – and said a

brief “Fine, boss, thanks.”

Don loved being in the lab. Though

he was a manager and not a scientist, he

was an increasingly enthusiastic student

of microbiology; every day, he learned

something new about the nutritional

benefits of Nutrorim’s products. He also

believed strongly in management by

walking around. From the start, he had

tried hard to foster a happy, participa-

tory, democratic culture at Nutrorim.

This had seemed relatively easy, since

most of the company’s employees hailed

from the Minneapolis area, where“Min-

nesota nice” was practically a state law.

It was also partly an act of defiance:

When Don was fresh out of business

school, he’d had a terrible run-in with

his boss, the dictatorial CEO of a retail

chain.

Of course, there were some excep-

tions to Minnesota nice, especially

among the more competitive, highly

analytical types in upper management.

Steve stopped at a table where a tech-

nician was mixing raspberry-colored

powder from two large canisters into

two beakers of water. “Hey, Jerri, mind

if Don does the blind taste test?” he

asked.

“Not at all, it would be an honor,”

Jerri replied, pouring some liquid from

a beaker into two cups.

“Shut your eyes,”said Steve. Don com-

plied, and Steve handed him one of the

cups.“Down the hatch.”

Sipping from the first cup, Don recog-

nized the familiar taste of ChargeUp.

It smelled like a combination of dried

raspberries, newly mowed grass, and

burnt toast.

“Here, take a sip of water before you

try the next one,” Steve offered. Don

drank some, then tried the second cup.

“So?” Steve inquired.

“No difference.” Don opened his eyes

and looked at Steve.

“That’s what we like to hear,” said

Steve. “The only real difference is that

the second cup is the one with Lipitrene

in it.”

“Ah,” said Don. Lipitrene, developed

in Nutrorim’s labs, was a new combina-

tion of organic oils and seeds that ap-

peared to enhance fat burning. Steve

wore his pride in the new ingredient like

a new father.

“We’ve finished with all the tests,

and now we’re gathering final input on

the taste,” Steve said, his eyes glinting.

“The handoff to marketing and sales

is already in gear.” He paused. “In fact,

is already in gear.” He paused. “In fact,

I was invited to the product marketing

meeting at 2:00. Any chance you’ll be

there?”

“I’ll drop in,” Don replied,“at least for

a minute.”

•••

The meeting started out peaceably

enough. Cynthia Pollington, the prod-

uct marketing manager, presented three

final designs for the new ChargeUp can-

ister, all of which had “Now with Lip-

itrene”splayed across them in large, em-

bossed letters. She asked everyone in

the room for feedback. In the end, the

majority – including Steve and Don –

liked the label with the gold letters. But

when asked for her opinion, Nora Stern,

a former entrepreneur whose company

had been acquired by Nutrorim the pre-

vious year, was recalcitrant.

“Do I have to vote?” she asked.

“Well, we’d like your opinion, yes,”

said Cynthia.

“Okay, here it is,” Nora responded.

“I know this whole thing is already a

done deal, but I don’t understand why

there was this huge need to improve

ChargeUp. It’s selling very well as it is.

Why fix something that isn’t broken?”

Steve shot back,“Nora,you don’t know

what you’re talking about.” Everyone

stared at Steve; the silence was palpable.

DECISION MAKING

Don jumped in, feeling the need to re-

store peace. “Tell you what, Nora and

Steve. Let’s take this off-line, OK?”

The Recall

By late September, at the end of the first

quarter, sales of ChargeUp with Lip-

itrene had leapfrogged the standard

product by 20% in the test market of

greater Minneapolis. Plans for a state-

wide launch, followed by a national one,

were well under way. Don was pleased.

In an all-staff meeting, he asked Steve

and the ChargeUp team to stand and be

recognized.“You have all demonstrated

the kind of gung ho spirit that makes

Nutrorim a leader,” he noted, nodding

to Steve while the audience broke into

applause.

•••

The phone call came on October 5.“Mr.

Rifkin?” said a male voice.“My name is

Matthew Norton, and I’m an investiga-

tor with the Minnesota state depart-

ment of health. I’m calling because

we’ve been investigating 11 cases of gas-

trointestinal distress among people who

took your ChargeUp supplement with

Lipitrene.”

“What? Are you sure?”

“Unfortunately, yes,” the inspector

responded.“The affected parties are all

members of Syd’s Gyms, and they all

June Rotenberg looked increasingly

grim. When Don finished, she spoke up.

“I just checked my voice mail,” she said.

“It was Linda Dervis at KXAQ radio. One

of the people who got sick must have

contacted her.” She looked around the

room.“Guys, once this news hits, things

are going to go downhill quickly.”

Jerry Garber, the general counsel,

chimed in. “I think we have no choice

but to pull ChargeUp off the shelves,”

he said.“If we don’t, we could be facing

a class action lawsuit. Talk about PR

problems…”

“Why are we even considering a re-

call?”asked Ned Horst, who headed the

Sports Supplements division. “There’s

nothing wrong with the product.I should

know, because I’ve been using it since it

came out.”

“I suspect you’re right,” Jerry added.

“And a recall will cost us.”

“Well, thank God we haven’t ex-

panded distribution yet,” said Don.

“Recalls are expensive,”said June.“But

under the circumstances, I’m with Jerry.

Besides, think about the cost of not re-

calling a potentially bad product.”

“Damn it, people, there’s no way

ChargeUp is unsafe!” Steve exclaimed,

slamming his hand down on the confer-

ence table. “We put Lipitrene through

enough. The public always seems to re-

member how a crisis is handled more

than the crisis itself. People will remem-

ber only how long it takes us to act.”

Suddenly everyone began talking at

once. Steve took an increasingly en-

trenched position against June, who

tried to get him to see things from the

public’s perspective. Ned worried openly

about Nutrorim’s relationships with

Syd’s Gyms and other channel partners.

Jerry tried to remind everyone of fa-

mous recall cases – the Tylenol crisis

faced by Johnson & Johnson, Suzuki’s

recall of its 2002 and 2003 auto mod-

els–and noted how the companies dealt

with them.

The din in the room grew louder and

louder. Don, frustrated, whistled every-

one to attention.

“Look, we’re getting nowhere,” he

said. “The first question here is, What

are the criteria for making a recall deci-

sion? What lenses should we use to

reach such an important decision? We

need that kind of framework to come up

with an answer, and we need that an-

swer fast. You, you, and you,” he said,

pointing to June, Jerry, and Ned. “Go

find out as much relevant data as you

can, and pull together an analysis in the

next 24 hours. I’ll meet with you, and

recall using the product there between

September 25 and 29. The victims range

in age from 19 to 55.”

Don felt the blood drain from his face.

“Are you telling me that the product has

to be recalled?”

“It seems like everything is a matter of debate.”

Nora sighed. “Ever since I came here, I’ve been

in too many meetings about meetings.”

“I don’t have the authority–or the ev-

idence – to make you do that. So for the

time being, I’d simply like your cooper-

ation in conducting an investigation. I

understand that distribution is limited

to the Twin Cities area, is that correct?”

“Yes.”

“That’s fortunate. Meanwhile, you

may want to consider a voluntary re-

call,” he said just before hanging up.

Don asked his assistant to call an

emergency meeting with the heads of

PR, sales, R&D, Sports Supplements,

and legal.

As he described his discussion with

the inspector to the team, PR director

two full years of testing. We ran all kinds

of toxicity studies in animals and on

human volunteers. Then we did another

tier of clinical trials in humans.” He

looked hard at June.“If you need me to

defend ChargeUp to the health depart-

ment, the reporters, or anyone else, I

have about 500,000 pages of documen-

tation to show them.”

“Of course we all believe you, Steve,”

June replied tentatively, “but that kind

of response can look like defensiveness,

and it can backfire.” She looked plead-

ingly at Don. “I’ve already drafted a

press release saying we’ll fully cooperate

with any investigation, but that’s not

we’ll form a preliminary view. I’m call-

ing all the senior managers for an 8 am

meeting tomorrow. You can present our

findings, and we’ll take a vote.”

He looked hard at Steve, who was

scowling. “Steve, I want you out of the

discussion for the time being. You’re a

little too passionate about this, and I

need some cool analysis here. You can

speak your mind at tomorrow’s meeting.”

The following morning, after hearing

the analyses and prognoses, the major-

ity of senior managers quickly agreed

with the subcommittee’s view that re-

calling the product was the only choice.

Following the meeting, June issued a

press release announcing the decision.

The release included a quote from Don,

assuring the public that Nutrorim was

“doing everything possible to cooperate

with the investigation.”

Two weeks later, Don received an-

other call from Matthew Norton.“I have

good news,” he said. “It turns out that

the people who got sick picked up a bug

from the gym’s smoothie bar.”

Don gasped.“So that means Nutrorim

is exonerated?” he asked.

“Yes, and fully,” the inspector replied.

“We’ll send out a press release saying so

today.”

Calling All Volunteers

The boardroom was abuzz as Nutrorim’s

15 top managers settled into their seats.

The consultant sat quietly on Don’s

right, sipping coffee.

“Okay, let’s get started,” said Don.

“As you all know, we’re going to hear

this morning from Synergy Consulting

Group’s Gibson Bryer, who will present

his preliminary findings. But first, let me

review quickly why I, with the full sup-

port of the board, wanted this process

review.”

Don reported that the board had

been heartened by a recent analyst’s

report calling the series of unfortunate

events with ChargeUp a “fluke” for an

“otherwise solid firm that has a history

of making sound decisions.”Despite the

fact that the analyst had recommended

a “buy,” the board members were con-

cerned about the damage to the Charge-

Up brand and adamant about making

absolutely sure that this type of thing

would never happen again. To that end,

the board strongly recommended a top-

to-toe process review. Gibson, having

worked with two CEOs who sat on the

board, was the “obvious choice” for a

consultant.

Someone turned down the lights as

the first PowerPoint slide appeared

on the conference room screen.“I want

to thank each of you for allowing me to

speak with you during the past month,”

the consultant began. “My initial find-

ings show areas of agreement and dis-

agreement about the effectiveness of the

decision-making process at Nutrorim.”

He clicked to another slide. “You told

me that for decisions with a certain

amount of built-in predictability – deci-

sions like how to improve your distribu-

tion network, whether to alter your

print ads – the process seems to work

really well.”He clicked to the next slide.

“But if a decision involves clear winners

and losers, it stalls.”Click.“A preliminary

survey about the inner workings of the

process itself, however, reveals mixed re-

views.” Click.

“Some of you feel that this company

is too consensus driven and that things

don’t get done in a timely fashion.”Click.

“Others say that the decision-making

process is fine the way it is. Still others

get a bit frustrated at times, wishing

that the CEO would make definitive

calls more often.” Click. “Some say that

the company deals well with tough is-

sues; others say that conflict is too often

suppressed or swept under the rug and

that this causes resentment.” Click.

“Some feel that the culture of the com-

pany is democratic and inclusive; oth-

ers worry that the louder voices and

squeakier wheels dominate. Lights up,

please. I’m assuming many of you have

questions.”

Some hands went up, and Bryer spent

45 minutes methodically addressing the

concerns. Don looked at the clock and

then stood up to thank him.“It’s almost

time for us to end this meeting, but be-

fore we do, I need three volunteers for a

subcommittee,”he said.“The next phase

of our work with Gibson is to come up

with a better, more resilient decision-

making process that works well both in

calm times and in rough. Anyone?”

No one volunteered. Then Anne Han-

nah, who headed the vitamin division,

and Ned Horst tentatively raised their

hands. Don looked around the room

and gazed at Nora, the former entre-

preneur. “Nora, I’d like you on the

team,” he said. “Your perspective is al-

ways invaluable.”

Just Make a Decision!

“Hey, Nora,”Steve said sarcastically, wav-

ing to her as the meeting disbanded,

“congratulations for volunteering. Jolly

good show.”

Don, who was talking to another

manager, pretended not to hear. A few

minutes later, he walked to Nora’s office

and tapped on the door.“Got a second?”

he said, poking his head in the door.

Nora nodded, and Don perched on

the corner of her desk. “You don’t look

very pleased about this,” Don said

soothingly.

“Well, no,” Nora said, clearly peeved.

“I’m completely buried in this market-

ing launch at the moment, and I have

other fish to fry. And to be honest,” she

went on, “I’m pretty tired of all this

navel-gazing nonsense.”

“Well, I picked you because you seem

to hold back in the senior management

meetings,” Don replied, trying his best

to be gentle. “You know, the ChargeUp

problem presented us with a real oppor-

tunity to look at what’s broken. You

come from outside the company, and

you have clever, fresh ideas. I think you

are just the person to bring these issues

to the fore.”

“Look, Don, I appreciate that, and I

completely sympathize with what you’re

trying to do. But I come from a com-

pany where all decisions were made in

the room. I didn’t allow anyone to leave

until a call was made. Here, it seems

like everything is a matter of debate.”

She sighed. “You know, this consultant-

driven committee is just more evidence

of what’s wrong. Ever since I came here,

I’ve been in too many meetings about

meetings.”

She tightened her lips. “Maybe it’s

time for you to take a more dictatorial

approach to decision making.”

What’s the right decision-making

process for Nutrorim? •

| I |

DECISION MAKING

DECISION MAKING

Christopher J. McCormick

is the president and CEO of

L.L.Bean in Freeport, Maine.

f I were to give points for good intentions,

then Don Rifkin would score pretty well.

He seems honest and genuinely interested in

doing the right thing. Both are laudable

attributes in a leader, but they go only so far.

Rifkin does not appear to have a problem

making decisions and, as evidenced by his

choice to launch the new and improved

ChargeUp, he appears to encourage creativ-

ity, innovation, and risk taking.

On the other hand, it seems that Rifkin has

created a culture devoid of candid inquiry,

where objective analysis and oversight take a

backseat to maintaining a “happy, participa-

tory, democratic culture.” As a consequence,

Rifkin now realizes that the outcomes of de-

cisions made in this kind of culture are lead-

ing to an unhealthy organizational dynamic,

paradoxically creating the type of corporate

culture he disdains.

Rifkin’s biggest problem is that he doesn’t

ask enough questions.I often say that my com-

pany’s greatest asset is its people, and that

this asset is at its best when engaged. Without

But how they utilize and play off the strengths

and skills of their in-house experts is key. This

ability to juggle skill sets includes knowing

how to leverage personalities so that each

team member is continually challenging

status-quo thinking and developing new

problem-solving techniques. For Rifkin in

particular, this skill also involves asking the

right questions of the people he relies on to

provide critical information. Granted, there is

an art to creating this type of engagement,

but it seems as though Rifkin doesn’t have

even the slightest idea how to initiate those

conversations.

A look back at how my organization re-

cently responded to a change in local labor

market conditions speaks to the value of this

interplay. As site work began on a new

L.L.Bean customer contact center, another

company announced its plans to locate an

even larger call center right next door. Be-

cause this development posed a reasonable

threat to our seasonal staffing needs, the

challenge I put forward to the organization

was “Is it too late to reconsider? What are

By asking the right questions of the experts

in his organization, Rifkin would put into

play healthy dynamics that would lead to

more cross-functional collaboration.

a culture of inquiry, engagement doesn’t hap-

pen. In addition to being a champion of inno-

vation, a CEO is responsible for constantly

assessing risk through questioning. Unfortu-

nately, Rifkin is not asking the types of ques-

tions that will create the environment of ac-

countability his organization needs to succeed.

By not probing the experts on his staff,

Rifkin has missed a huge opportunity to re-

shape the culture of his organization and es-

tablish himself as a strong leader. A stricter

mode of inquiry would have, among other

things, made the decision about whether to

recall ChargeUp much easier.

Of course, it must be understood that suc-

cessful top managers are rarely experts in

more than a few organizational disciplines.

our options, and what are the costs?” These

questions led to countless others that imme-

diately mobilized the entire company to con-

sider alternatives, despite the fact that ground

had already been broken. The result is that

we found a new location and started opera-

tions in the same amount of time and on bet-

ter terms than we had for the original project.

Rifkin’s challenge is complicated by the fact

that his decision-making process has led to a

reactionary culture characterized by consider-

able resentment and second-guessing on the

part of his management team.With a renewed

focus on inquiry, Rifkin would experience two

important benefits. First, he would create ac-

cess to the information he needs to make bet-

ter decisions.Second,he would set an example

for his own managers that speaks to the value

of diligence and personal accountability.

By asking people the right questions,

Rifkin would put into play healthy dynamics

that would lead to more cross-functional col-

laboration, greater acceptance of decisions,

and better business results in which his en-

tire team would feel more fully vested.

DECISION MAKING

DECISION MAKING

| R |

former boss and has strived to form a

corporate culture that takes into account

the “Minnesota niceness” of most of his em-

ployees. While these objectives are good

starting points, the lack of consistency in

The decision-making crisis at

Nutrorim is a blessing in disguise,

for it offers Rifkin a chance to

install irm management rules and

build trust within the company.

Rifkin’s approach to management and deci-

sion making undermines trust. It’s difficult

for teams to function well together when

there is so much inconsistency and volatility

at work.

Let’s start with Rifkin’s leadership style. In

the case of the bad stock purchase, he showed

poor judgment, a lack of professionalism, and

an inability to view facts objectively. In addi-

tion to not taking simple business precau-

tions by personally vetting Dipensit, Rifkin

demonstrated selective hearing that kept

him from absorbing dissent.

The picture is different in the case of the

recall. If you look at it from the perspective

of decision theory, Rifkin reacted in a rational

manner. Nutrorim faced two scenarios: Ei-

ther ChargeUp with Lipitrene would be found

all quality of decision making. Fortunately,

there are a few things he can do to improve

matters. First, he should demonstrate strong

leadership by setting firm management pro-

cess rules – especially for investment and

M&A decisions, product launches, and risk

management – that are easy to apply and

transparent to everyone.

M&A decisions, for example, should be

formed on the basis of precisely defined cri-

teria that cover everything from due dili-

gence, strategic and operational aspects of

the merger, and a clear exit strategy. Trans-

parent rules prevent management from

growing too bullish, practicing selective hear-

ing, and ignoring risks. They also go a long

way toward establishing trust, because peo-

ple know what to expect and what they’re

responsible for.

I would also recommend that Rifkin un-

dergo intensive coaching to help him de-

velop a consistent leadership style and learn

to take a more active role in managing his

team. Coaching could help Rifkin do a better

job of developing his people. For example,

it’s clear that Nora Stern is a hands-on man-

ager, rather than a talker, so Rifkin should

keep her on practical tasks – such as giving

her responsibility for a plant where she can

develop her skills–rather than force her onto

subcommittees. He should also let his man-

agers know what is expected of them, espe-

cially in terms of team behavior. He can

praise Steve Ford for his R&D expertise but

Hauke Moje (hauke_moje

@de.rolandberger.com) is

a partner at Roland Berger

Strategy Consultants in

Hamburg, Germany.

to be the cause of the customers’ illness, or it

would not. Likewise, Nutrorim had two op-

tions: Recall the product, or don’t. If the

product turned out to be faulty, keeping it on

the market would most likely have meant the

company’s demise, given the possibility of

a lawsuit. Management could not take that

risk, since the probability of the product

being faulty was obviously beyond a negligi-

ble level and there was no time for further in-

vestigation. Rifkin did a good job of hearing

people out and decisively following the sub-

committee’s recommendation to withdraw

the product immediately.

But Rifkin’s inconsistent approach to these

events undercuts his authority and the over-

make him understand that his is only one

viewpoint among many, and that he must

remain a team player even if he does not

agree with particular decisions.

As the Swiss novelist Max Frisch wrote,“A

crisis is a productive situation–you only have

to take away the flavor of catastrophe.” The

decision-making crisis at Nutrorim is a bless-

ing in disguise, for it offers Rifkin a chance to

install firm management rules. And Rifkin

can build trust within his management team

by setting an example and openly commu-

nicating his intentions and goals for the

company. In accomplishing both, he’s doing

what is necessary to improve the company’s

decision-making processes.

DECISION MAKING

DECISION MAKING

“What’s the right decision-making process for

Nutrorim?” raises another question: “What’s the

right decision-making process for Don Rifkin?”

| I |

columbia.edu) is a professor

of professional practice in

the management division of

Columbia Business School in

New York.

agree with Gibson Bryer that the current

decision-making process at Nutrorim

seems to work fine for decisions with some

built-in predictability but not for those with

clear winners and losers. Day-to-day opera-

tional and procedural issues are one thing;

important problems or strategic matters that

involve conflict or debate are quite another.

And when it comes to the latter, the process

at Nutrorim is broken.

The problems with the decision-making

process at Nutrorim stem primarily from

Rifkin’s aversion to conflict. He believes that

he keeps the process open and asks for input,

but he doesn’t realize that his approach to

building a friendly culture squelches dissent

and debate. He’s trying to build a “nice” cul-

ture by making it homogeneous, and that’s

causing trouble. Murmurs go unaddressed,

opinions are unbalanced, top managers feel

increasingly frustrated, and bad decisions are

the norm. Hence, the final question–“What’s

the right decision-making process for Nu-

trorim?”–raises another question:“What’s the

right decision-making process for Rifkin?”

It would help if Rifkin could view conflict

as an important source of energy and see

that it’s his responsibility to understand all

sides of an issue. To do this, he needs to ex-

plore his own issues first. If I were coaching

him, I would begin by asking him why he

hasn’t investigated the “murmurs” he’s over-

heard, and why he chooses to deal with con-

flict in private rather than in public. I might

ask,“How has the decision to take things off-

line helped you in the past? What are the

benefits and drawbacks of doing things this

way?” The difficulties he’s had with his man-

agers reflect his aversion to conflict. All lead-

ers face people like Steve Ford from time to

time. Commitment and passion are worth

encouraging in direct reports, but assertive-

ness and conviction can have their down-

sides. To become more comfortable dealing

with people who possess these qualities, par-

ticularly in group settings, Rifkin needs to

get away from his and others’ personal feel-

ings. In a group meeting, he could say, for ex-

ample,“We’ve heard a strong case for Y. Does

anyone else have data or experiences that

might suggest another approach?”

Rifkin should also take a good, hard look at

the way he selects members of his subcom-

mittees. In his desire to avoid disagreements,

he seems to seek out homogeneity. Public re-

lations and legal, for example, are corporate

kindred spirits, and leaving the head of R&D

out of a discussion on a product recall looks

a lot like deck stacking. If Rifkin wants a better

balance of views and, hence, better decisions,

he should choose members more carefully.

Nora Stern makes an important point

when she says that in her former company,

debate was held out in the open, and differ-

ences were worked out in the group. Follow-

ing this example would cut down on the frus-

tration among Rifkin’s managers, reduce

lobbying, and bring to light some key opin-

ions. I recommend that Rifkin use subgroups

to gather data, identify assumptions, and cre-

ate options. Each subgroup should report

regularly to the larger group, which can then

debate a given issue’s pros and cons. These

groups can be set up like teams of lawyers,

with one critical exception: Those individu-

als with the strongest opinions should argue

the case for the opposing side. This kind of

decision-making structure can go a long way

toward unearthing the opinions of all in-

volved, including those who feel left out, and

toward building the kind of balance Rifkin

needs to develop in his company.

I would stress to Rifkin that he has two pri-

mary responsibilities: to guide the decision-

making process so that all the data, opinions,

assumptions, and options are identified and

fairly discussed, and to make the final deci-

sions. It would also help if he explained the

reasoning behind his decisions to his direct

reports.

What’s the Right Decision-Making Process for Nutrorim? >> C A S E C O M M E N TA R Y

What’s the Right Decision-Making Process for Nutrorim? >> C A S E C O M M E N TA R Y

| N |

Nora Stern, as the outsider, is the voice

of reason when she notes that there is too

much navel-gazing at the company. Too

many people, including Rifkin, are operat-

ing on hunches and gut reactions that could

put the company at risk. Rifkin abdicates his

responsibility when he fails to sponsor a

learning organization that builds knowledge

as a competitive advantage. He needs to

show leadership and a willingness to make

decisions.

The stock purchase is a perfect case in

point. The CFO, Laurence Wiseman, may

have his talents, but it seems he pushed

through the decision to purchase stock in

Dipensit without exercising due diligence.

Investing in a company is like buying a

house: One makes the purchase decision

based on a combination of hard factors such

as price, condition, and school system, as

well as soft factors such as general impres-

sions, conversations with neighbors, and so

on. It is inexcusable that Rifkin allowed share-

holders’ money to be spent on a stake in

Rifkin can’t allow his team members to

create their own versions of reality. For exam-

ple, Ford, the R&D head with vested inter-

ests and a difficult personality, prevents

people from having candid conversations

when they are most needed – during times

of crisis. Rifkin needs to buckle down and

make it clear to Ford and everyone else that

they will be held accountable for their ac-

tions and their results and that no one gets to

steamroll others. Without this rule, the com-

pany can only react after the horse has left

the stable.

To ensure better decision making, Rifkin

should work hard to create a culture that re-

wards on the basis of unit performance as

well as individual contributions. He should

spend more time developing leaders – I like

to think of them as mini-CEOs – who have a

passion for results and understand how their

actions affect the company. Rifkin’s job is to

monitor his managers’ progress, motivate

them, and give them feedback. He should

make sure that results are openly celebrated

and that when failure occurs, everyone learns

Paul Domorski (pdomorski@

avaya.com) is the vice presi-

dent of service operations at

Avaya, a communications

network and service provider

in Basking Ridge, New Jersey.

The payoff for a lot of hard work and seemingly endless

preparation occurs when it’s time to make hard decisions.

Dipensit without having launched a thor-

ough investigation of the CEO’s background

when questions first arose. Rifkin and his

team should have delved into any rumors,

probed any allegations, studied the business

model, and fully understood any contractual

obligations.

The same fact-finding failure occurred

with the ChargeUp fiasco, which should have

been investigated immediately. Rifkin should

have dispatched a qualified team to Syd’s

Gyms to investigate the facts and interview

the people affected. Ford and his team should

have reviewed the allegations in light of ear-

lier toxicity studies and clinical trials to deter-

mine whether any of the alleged problems

had ever occurred during testing. Indeed, a

thorough investigation might have prevented

the crisis in the first place.

from it. Like members of a sports team, every

one of these individuals is accountable for

his or her own assignment. Without that

accountability, the team cannot win. In the

end, Rifkin should play the role of a quarter-

back and be the one calling all the plays.

Getting this role right sometimes leads to

tough discussions, but the results can be

outstanding.

Sometimes the answers to dilemmas will

be obvious; other times, more analysis will be

required. Either way, the teams at Nutrorim

must do a better job of getting at the heart of

problems. The payoff for a lot of hard work

and seemingly endless preparation occurs

when it’s time to make hard decisions.

.

American Revolution and War for Independence

Prepared by

Master’s Degree

student

Alexander Druzik

Scientific supervises

Senior Lecturer

V. Shimansky

Minsk 2014

Date: 2014-12-29; view: 1001

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| All the Wrong Moves | | | Introduction |