CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

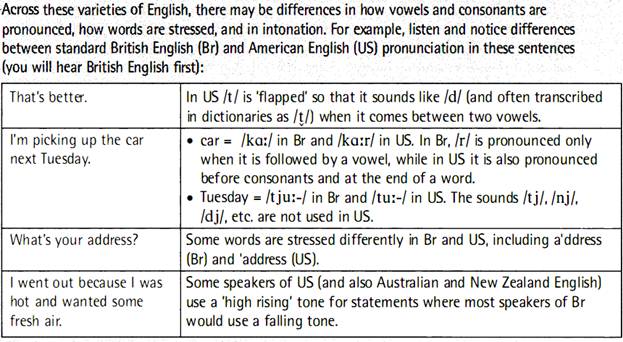

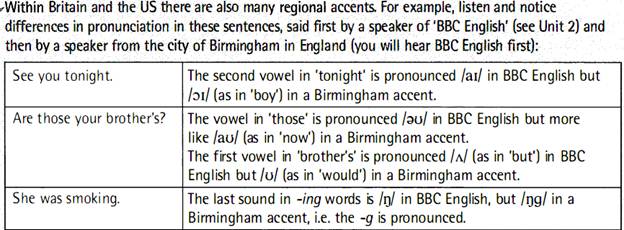

Accents and varieties of English

Peak Attention and Alternative Attention Sources

I am not sure who first came up with the term Peak Attention, but the analogy to Peak Oil is surprisingly precise. It has its critics, but I think the model is basically correct.

Peak Oil refers to a graph of oil production with a maximum called Hubbert’s peak, that represents peak oil production. The theory behind it is that new oil reserves become harder to find over time, are smaller in size, and harder to mine. You have to look harder and work harder for every new gallon, new wells run dry faster than old ones, and the frequency of discovery goes down. You have to drill more.

There is certainly plenty of energy all around (the Sun and the wind, to name two sources), but oil represents a particularly high-value kind.

Attention behaves the same way. Take an average housewife, the target of much time mining early in the 20th century. It was clear where her attention was directed. Laundry, cooking, walking to the well for water, cleaning, were all obvious attention sinks. Washing machines, kitchen appliances, plumbing and vacuum cleaners helped free up a lot of that attention, which was then immediately directed (as corporate-captive attention) to magazines and television.

But as you find and capture most of the wild attention, new pockets of attention become harder to find. Worse, you now have to cannibalize your own previous uses of captive attention. Time for TV must be stolen from magazines and newspapers. Time for specialized entertainment must be stolen from time devoted to generalized entertainment.

Sure, there is an equivalent to the Sun in the picture. Just ask anyone who has tried mindfulness meditation, and you’ll understand why the limits to attention (and therefore the value of time) are far further out than we think.

The point isn’t that we are running out of attention. We are running out of the equivalent of oil: high-energy-concentration pockets of easily mined fuel.

The result is a spectacular kind of bubble-and-bust.

Each new pocket of attention is harder to find: maybe your product needs to steal attention from that one TV obscure show watched by just 3% of the population between 11:30 and 12:30 AM. The next displacement will fragment the attention even more. When found, each new pocket is less valuable. There is a lot more money to be made in replacing hand-washing time with washing-machine plus magazine time, than there is to be found in replacing one hour of TV with a different hour of TV.

What’s more, due to the increasingly frantic zero-sum competition over attention, each new “well” of attention runs out sooner. We know this idea as shorter product lifespans.

So one effect of Peak Attention is that every human mind has been mined to capacity using attention-oil drilling technologies. To get to Clay Shirky’s hypothetical notion of cognitive surplus, we need Alternative Attention sources.

To put it in terms of per-capita productivity gains, we hit a plateau.

We can now connect the dots to Zakaria’s reading of global GDP trends, and explain why the action is shifting back to Asia, after being dominated by Europe for 600 years.

Europe may have increased per capita productivity 594% in 600 years, while China and India stayed where they were, but Europe has been slowing down and Asia has been catching up. When Asia hits Peak Attention (America is already past it, I believe), absolute size, rather than big productivity differentials, will again define the game, and the center of gravity of economic activity will shift to Asia.

If you think that’s a long way off, you are probably thinking in terms of living standards rather than attention and energy. In those terms, sure, China and India have a long way to go before catching up with even Southeast Asia. But standard of living is the wrong variable. It is a derived variable, a function of available energy and attention supply. China and India willnever catch up (though Western standards of living will decline), but Peak Attention will hit both countries nevertheless. Within the next 10 years or so.

What happens as the action shifts? Kaplan’s Monsoon frames the future in possibly the most effective way. Once again, it is the oceans, rather than land, that will become the theater for the next act of the human drama. While American lifestyle designers are fleeing to Bali, much bigger things are afoot in the region.

And when that shift happens, the Schumpeterian corporation, the oil rig of human attention, will start to decline at an accelerating rate. Lifestyle businesses and other oddball contraptions — the solar panels and wind farms of attention economics — will start to take over.

It will be the dawn of the age of Coasean growth.

Adam Smith’s fundamental ideas helped explain the mechanics of Mercantile economics and the colonization of space.

Joseph Schumpeter’s ideas helped extend Smith’s ideas to cover Industrial economics and the colonization of time.

Ronald Coase turned 100 in 2010. He is best known for his work on transaction costs, social costs and the nature of the firm. Where most classical economists have nothing much to say about the corporate form, for Coase, it has been the main focus of his life.

Without realizing it, the hundreds of entrepreneurs, startup-studios and incubators, 4-hour-work-weekers and lifestyle designers around the world, experimenting with novel business structures and the attention mining technologies of social media, are collectively triggering the age of Coasean growth.

Coasean growth is not measured in terms of national GDP growth. That’s a Smithian/Mercantilist measure of growth.

It is also not measured in terms of 8% returns on the global stock market. That is a Schumpeterian growth measure. For that model of growth to continue would be a case of civilizational cancer (“growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell” as Edward Abbey put it).

Coasean growth is fundamentally not measured in aggregate terms at all. It is measured in individual terms. An individual’s income and productivity may both actually decline, with net growth in a Coasean sense.

How do we measure Coasean growth? I have no idea. I am open to suggestions. All I know is that the metric will need to be hyper-personalized and relative to individuals rather than countries, corporations or the global economy. There will be a meaningful notion of Venkat’s rate of Coasean growth, but no equivalent for larger entities.

The fundamental scarce resource that Coasean growth discovers and colonizes is neither space, nor time. It is perspective.

The bad news: it too is a scarce resource that can be mined to a Peak Perspective situation.

The good news: you will likely need to colonize your own unclaimed perspective territory. No collectivist business machinery will really be able to mine it out of you.

Those are stories for another day. Stay tuned.

Note #1: This post weighs in at over 7000 words and is a new record for me.

Note #2: I hope those of you who have read Tempo got about 34.2% more value out of this post.

Note #3: Yeah, I am opening up a new blogging battlefront, after nearly two years of pussyfooting around geopolitics and globalization via things like container shipping and garbage. Frankly, I’ve been meaning to for a while, but simply wasn’t ready.

Accents and varieties of English

(A2)

(A3)

Date: 2014-12-29; view: 1238

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| III. Coasean Growth and the Perspective Economy | | | EXERCISES |