CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Reach versus Power

The second thing to understand about the evolution of the corporation is that the apogee ofpower did not coincide with the apogee of reach. In the 1780s, only a small fraction of humanity was employed by corporations, but corporations were shaping the destinies of empires. In the centuries that followed the crash of 1772, the power of the corporation was curtailed significantly, but in terms of sheer reach, they continued to grow, until by around 1980, a significant fraction of humanity was effectively being governed by corporations.

I don’t have numbers for the whole world, but for America, less than 20% of the population had paycheck incomes in 1780, and over 80% in 1980, and the percentage has been declining since (I have cited these figures before; they are from Gareth Morgan’s Images of Organization and Dan Pink’s Free Agent Nation). Employment fraction is of course only one of the many dimensions of corporate power (which include economic, material, cultural, human and political forms of power), but this graph provides some sense of the numbers behind the rise and fall of the corporation as an idea.

It is tempting to analyze corporations in terms of some measure of overall power, which I call “reach.” Certainly corporations today seem far more powerful than those of the 1700s, but the point is that the form is much weaker today, even though it has organized more of our lives. This is roughly the same as the distinction between fertility of women and population growth: the peak in fertility (a per-capita number) and peak in population growth rates (an aggregate) behave differently.

To make sense of the form, the divide between the Smithian and Schumpeterian growth epochs is much more useful than the dynamics of reach. This gives us a useful 3-phase model of the history of the corporation: the Mercantilist/Smithian era from 1600-1800, the Industrial/Schumpeterian era from 1800 – 2000 and finally, the era we are entering, which I will dub the Information/Coasean era. By a happy accident, there is a major economist whose ideas help fingerprint the economic contours of our world: Ronald Coase.

This post is mainly about the two historical phases, and are in a sense a macro-prequel to the ideas I normally write about which are more individual-focused and future-oriented.

I: Smithian Growth and the Mercantilist Economy (1600 – 1800)

The story of the old corporation and the sea

It is difficult for us in 2011, with Walmart and Facebook as examples of corporations that significantly control our lives, to understand the sheer power the East India Company exercised during its heyday. Power that makes even the most out-of-control of today’s corporations seem tame by comparison. To a large extent, the history of the first 200 years of corporate evolution is the history of the East India Company. And despite its name and nation of origin, to think of it as a corporation that helped Britain rule India is to entirely misunderstand the nature of the beast.

Two images hint at its actual globe-straddling, 10x-Walmart influence: the image of the Boston Tea Partiers dumping crates of tea into the sea during the American struggle for independence, and the image of smoky opium dens in China. One image symbolizes the rise of a new empire. The other marks the decline of an old one.

The East India Company supplied both the tea and the opium.

At a broader level, the EIC managed to balance an unbalanced trade equation between Europe and Asia whose solution had eluded even the Roman empire. Massive flows of gold and silver from Europe to Asia via the Silk and Spice routes had been a given in world trade for several thousand years. Asia simply had far more to sell than it wanted to buy. Until the EIC came along

A very rough sketch of how the EIC solved the equation reveals the structure of value-addition in the mercantilist world economy.

The EIC started out by buying textiles from Bengal and tea from China in exchange for gold and silver.

Then it realized it was playing the same sucker game that had trapped and helped bankrupt Rome.

Next, it figured out that it could take control of the opium industry in Bengal, trade opium for tea in China with a significant surplus, and use the money to buy the textiles it needed in Bengal. Guns would be needed.

As a bonus, along with its partners, it participated in yet another clever trade: textiles for slaves along the coast of Africa, who could be sold in America for gold and silver.

For this scheme to work, three foreground things and one background thing had to happen: the corporation had to effectively take over Bengal (and eventually all of India), Hong Kong (and eventually, all of China, indirectly) and England. Robert Clive achieved the first goal by 1757. An employee of the EIC, William Jardine, founded what is today Jardine Matheson, the spinoff corporation most associated with Hong Kong and the historic opium trade. It was, during in its early history, what we would call today a narco-terrorist corporation; the Taliban today are kindergarteners in that game by comparison. And while the corporation never actually took control of the British Crown, it came close several times, by financing the government during its many troubles.

The background development was simpler. England had to take over the oceans and ensure the safe operations of the EIC.

Just how comprehensively did the EIC control the affairs of states? Bengal is an excellent example. In the 1600s and the first half of the 1700s, before the Industrial Revolution, Bengali textiles were the dominant note in the giant sucking sound drawing away European wealth (which was flowing from the mines and farms of the Americas). The European market, once the EIC had shoved the Dutch VOC aside, constantly demanded more and more of an increasing variety of textiles, ignoring the complaining of its own weavers. Initially, the company did no more than battle the Dutch and Portuguese on water, and negotiate agreements to set up trading posts on land. For a while, it played by the rules of the Mughal empire and its intricate system of economic control based on various imperial decrees and permissions. The Mughal system kept the business world firmly subservient to the political class, and ensured a level playing field for all traders. Bengal in the 17th and 18th centuries was a cheerful drama of Turks, Arabs, Armenians, Indians, Chinese and Europeans. Trade in the key commodities, textiles, opium, saltpeter and betel nuts, was carefully managed to keep the empire on top.

But eventually, as the threat from the Dutch was tamed, it became clear that the company actually had more firepower at its disposal than most of the nation-states it was dealing with. The realization led to the first big domino falling, in the corporate colonization of India, at the battle of Plassey. Robert Clive along with Indian co-conspirators managed to take over Bengal, appoint a puppet Nawab, and get himself appointed as the Mughal diwan (finance minister/treasurer) of the province of Bengal, charged with tax collection and economic administration on behalf of the weakened Mughals, who were busy destroying their empire. Even people who are familiar enough with world history to recognize the name Robert Clive rarely understand the extent to which this was the act of a single sociopath within a dangerously unregulated corporation, rather than the country it was nominally subservient to (England).

This history doesn’t really stand out in sharp relief until you contrast it with the behavior of modern corporations. Today, we listen with shock to rumors about the backroom influence of corporations like Halliburton or BP, and politicians being in bed with the business leaders in the Too-Big-to-Fail companies they are supposed to regulate.

The EIC was the original too-big-to-fail corporation. The EIC was the beneficiary of the original Big Bailout. Before there was TARP, there was the Tea Act of 1773 and the Pitt India Act of 1783. The former was a failed attempt to rein in the EIC, which cost Britain the American Colonies. The latter created the British Raj as Britain doubled down in the east to recover from its losses in the west. An invisible thread connects the histories of India and America at this point. Lord Cornwallis, the loser at the Siege of Yorktown in 1781 during the revolutionary war, became the second Governor General of India in 1786.

But these events were set in motion over 30 years earlier, in the 1750s. There was no need for backroom subterfuge. It was all out in the open because the corporation was such a new beast, nobody really understood the dangers it represented. The EIC maintained an army. Itsmerchant ships often carried vastly more firepower than the naval ships of lesser nations. Its officers were not only not prevented from making money on the side, private trade was actually a perk of employment (it was exactly this perk that allowed William Jardine to start a rival business that took over the China trade in the EIC’s old age). And finally — the cherry on the sundae — there was nothing preventing its officers like Clive from simultaneously holdingpolitical appointments that legitimized conflicts of interest. If you thought it was bad enough that Dick Cheney used to work for Halliburton before he took office, imagine if he’d worked there while in office, with legitimate authority to use his government power to favor his corporate employer and make as much money on the side as he wanted, and call in the Army and Navy to enforce his will. That picture gives you an idea of the position Robert Clive found himself in, in 1757.

He made out like a bandit. A full 150 years before American corporate barons earned the appellation “robber.”

In the aftermath of Plassey, in his dual position of Mughal diwan of Bengal and representative of the EIC with permission to make money for himself and the company, and the armed power to enforce his will, Clive did exactly what you’d expect an unprincipled and enterprising adventurer to do. He killed the golden goose. He squeezed the Bengal textile industry dry for profits, destroying its sustainability. A bubble in London and a famine in Bengal later, the industry collapsed under the pressure (Bengali economist Amartya Sen would make his bones and win the Nobel two centuries later, studying such famines). With industrialization and machine-made textiles taking over in a few decades, the economy had been destroyed. But by that time the EIC had already moved on to the next opportunities for predatory trade: opium and tea.

The East India bubble was a turning point. Thanks to a rare moment of the Crown being more powerful than the company during the bust, the bailout and regulation that came in the aftermath of the bubble fundamentally altered the structure of the EIC and the power relations between it and the state. Over the next 70 years, political, military and economic power were gradually separated and modern checks and balances against corporate excess came into being.

The whole intricate story of the corporate takeover of Bengal is told in detail in Robins’ book. The Battle of Plassey is actually almost irrelevant; most of the action was in the intrigue that led up to it, and followed. Even if you have some familiarity with Indian and British history during that period, chances are you’ve never drilled down into the intricate details. It has all the elements of a great movie: there is deceit, forgery of contracts, licensing frauds, murder, double-crossing, arm-twisting and everything else you could hope for in a juicy business story.

As an enabling mechanism, Britain had to rule the seas, comprehensively shut out the Dutch, keep France, the Habsburgs, the Ottomans (and later Russia) occupied on land, and have enough firepower left over to protect the EIC’s operations when the EIC’s own guns did not suffice. It is not too much of a stretch to say that for at least a century and a half, England’s foreign policy was a dance in Europe in service of the EIC’s needs on the oceans. That story, with much of the action in Europe, but most of the important consequences in America and Asia, is told in Mahan’s book. (Though boats were likely invented before the wheel, surprisingly, the huge influence of sea power upon history was not generally recognized until Mahan wrote his classic. The book is deep and dense. It’s worth reading just for the story of how Rome defeated Carthage through invisible negative-space non-action on the seas by the Roman Navy. I won’t dive into the details here, except to note that Mahan’s book is theessential lens you need to understand the peculiar military conditions in the 17th and 18th centuries that made the birth of the corporation possible.)

To read both books is to experience a process of enlightenment. An illegible period of world history suddenly becomes legible. The broad sweep of world history between 1500-1800 makes no real sense (between approximately the decline of Islam and the rise of the British Empire) except through the story of the EIC and corporate mercantilism in general.

The short version is as follows.

Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in 1453 and the last Muslim ruler was thrown out of Spain in 1492, the year Columbus sailed the ocean blue. Vasco de Gama found a sea route to India in 1498. The three events together caused a defensive consolidation of Islam under the later Ottomans, and an economic undermining of the Islamic world (a process that would directly lead to the radicalization of Islam under the influence of religious leaders like Abd-al Wahhab (1703-1792)).

The 16th century makes a vague sort of sense as the “Age of Exploration,” but it really makes a lot more sense as the startup/first-mover/early-adopter phase of the corporate mercantilism. The period was dominated by the daring pioneer spirit of Spain and Portugal, which together served as the Silicon Valley of Mercantilism. But the maritime business operations of Spain and Portugal turned out to be the MySpace and Friendster of Mercantilism: pioneers who could not capitalize on their early lead.

Conventionally, it is understood that the British and the Dutch were the ones who truly took over. But in reality, it was two corporations that took over: the EIC and the VOC (the Dutch East India Company, Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, founded one year after the EIC)the Facebook and LinkedIn of Mercantile economics respectively. Both were fundamentally more independent of the nation states that had given birth to them than any business entities in history. The EIC more so than the VOC. Both eventually became complex multi-national beasts.

A lot of other stuff happened between 1600 – 1800. The names from world history are familiar ones: Elizabeth I, Louis XIV, Akbar, the Qing emperors (the dynasty is better known than individual emperors) and the American Founding Fathers. The events that come to mind are political ones: the founding of America, the English Civil War, the rise of the Ottomans and Mughals.

The important names in the history of the EIC are less well-known: Josiah Child, Robert Clive, Warren Hastings. The events, like Plassey, seem like sideshows on the margins of land-based empires.

The British Empire lives on in memories, museums and grand monuments in two countries. Company Raj is largely forgotten. The Leadenhall docks in London, the heart of the action, have disappeared today under new construction.

But arguably, the doings of the EIC and VOC on the water were more important than the pageantry on land. Today the invisible web of container shipping serves as the bloodstream of the world. Its foundations were laid by the EIC.

For nearly two centuries they ruled unchallenged, until finally the nations woke up to their corporate enemies on the water. With the reining in and gradual decline of the EIC between 1780 and 1857, the war between the next generation of corporations and nations moved to a new domain: the world of time.

The last phase of Mercantilism eventually came to an end by the 1850s, as events ranging from the first war of Independence in India (known in Britain as the Sepoy Mutiny), the first Opium War and Perry prying Japan open signaled the end of the Mercantilist corporation worldwide. The EIC wound up its operations in 1876. But the Mercantilist corporation died many decades before that as an idea. A new idea began to take its place in the early 19th century: the Schumpeterian corporation that controlled, not trade routes, but time. It added the second of the two essential Druckerian functions to the corporation: innovation.

II. Schumpeterian Growth and the Industrial Economy (1800 – 2000)

The colonization of time and the apparently endless frontier

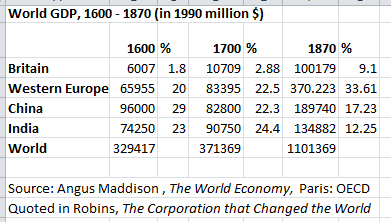

To understand what changed in 1800, consider this extremely misleading table about GDP shares of different countries, between 1600-1870. There are many roughly similar versions floating around in globalization debates, and the numbers are usually used gleefully to shock people who have no sense of history. I call this the “most misleading table in the world.”

Chinese and Indian jingoists in particular, are prone to misreading this table as evidence that colonization “stole” wealth from Asia (the collapse of GDP share for China and India actually went much further, into the low single digits, in the 20th century). The claim of GDP theft is true if you use a zero-sum Mercantilist frame of reference (and it is true in a different sense of “steal” that this table does not show).

But the Mercantilist model was already sharply declining by 1800.

Something else was happening, and Fareed Zakaria, as far as I know, is the only major commentator to read this sort of table correctly, in The Post-American World. He notes that what matters is not absolute totals, but per-capita productivity.

We get a much clearer picture of the real standing of countries if we consider economic growth and GDP per capita. Western Europe GDP per capita was higher than that of both China and India by 1500; by 1600 it was 50% higher than China’s. From there, the gap kept growing. Between 1350 and 1950 — six hundred years — GDP per capita remained roughly constant in India and China (hovering around $600 for China and $550 for India). In the same period, Western European GDP per capita went from $662 to $4,594, a 594 percent increase.

Sure, corporations and nations may have been running on Mercantilist logic, but the undercurrent of Schumpeterian growth was taking off in Europe as early as 1500 in the less organized sectors like agriculture. It was only formally recognized and tamed in the early 1800s, but the technology genie had escaped.

The action shifted to two huge wildcards in world affairs of the 1800s: the newly-born nation of America and the awakening giant in the east, Russia. Per capita productivity is about efficient use of human time. But time, unlike space, is not a collective and objective dimension of human experience. It is a private and subjective one. Two people cannot own the same piece of land, but they can own the same piece of time. To own space, you control it by force of arms. To own time is to own attention. To own attention, it must first be freed up, one individual stream of consciousness at a time.

The Schumpeterian corporation was about colonizing individual minds. Ideas powered by essentially limitless fossil-fuel energy allowed it to actually pull it off.

By the mid 1800s, as the EIC and its peers declined, the battle seemingly shifted back to land, especially in the run-up to and aftermath of, the American Civil War. I haven’t made complete sense of the Russian half of the story, but that peaked later and ultimately proved less important than the American half, so it is probably reaosonably safe to treat the story of Schumpeterian growth as an essentially American story.

If the EIC was the archetype of the Mercantilist era, the Pennsylvania Railroad company was probably the best archetype for the Schumpeterian corporation. Modern corporate management as well Soviet forms of statist governance can be traced back to it. In many ways the railroads solved a vastly speeded up version of the problem solved by the EIC: complex coordination across a large area. Unlike the EIC though, the railroads were built around the telegraph, rather than postal mail, as the communication system. The difference was like the difference between the nervous systems of invertebrates and vertebrates.

If the ship sailing the Indian Ocean ferrying tea, textiles, opium and spices was the star of the mercantilist era, the steam engine and steamboat opening up America were the stars of the Schumpeterian era. Almost everybody misunderstood what was happening. Traveling up and down the Mississippi, the steamboat seemed to be opening up the American interior. Traveling across the breadth of America, the railroad seemed to be opening up the wealth of the West, and the great possibilities of the Pacific Ocean.

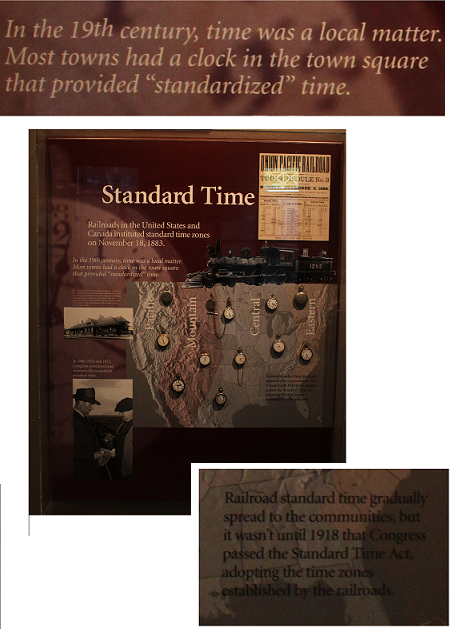

Those were side effects. The primary effect of steam was not that it helped colonize a new land, but that it started the colonization of time. First, social time was colonized. The anarchy of time zones across the vast expanse of America was first tamed by the railroads for the narrow purpose of maintaining train schedules, but ultimately, the tools that served to coordinate train schedules: the mechanical clock and time zones, served to colonize human minds. An exhibit I saw recently at the Union Pacific Railroad Museum in Omaha clearly illustrates this crucial fragment of history:

The steam engine was a fundamentally different beast than the sailing ship. For all its sophistication, the technology of sail was mostly a very-refined craft, not an engineering discipline based on science. You can trace a relatively continuous line of development, with relatively few new scientific or mathematical ideas, from early Roman galleys, Arab dhows and Chinese junks, all the way to the amazing Tea Clippers of the mid 19th century (Mokyr sketches out the story well, as does Mahan, in more detail).

Steam power though was a scientific and engineering invention. Sailing ships were the crowning achievements of the age of craft guilds. Steam engines created, and were created by engineers, marketers and business owners working together with (significantly disempowered) craftsmen in genuinely industrial modes of production. Scientific principles about gases, heat, thermodynamics and energy applied to practical ends, resulting in new artifacts. The disempowerment of craftsmen would continue through the Schumpeterian age, until Fredrick Taylor found ways to completely strip mine all craft out of the minds of craftsmen, and put it into machines and the minds of managers. It sounds awful when I put it that way, and it was, in human terms, but there is no denying that the process was mostly inevitable and that the result was vastly better products.

The Schumpeterian corporation did to business what the doctrine of Blitzkrieg would do to warfare in 1939: move humans at the speed of technology instead of moving technology at the speed of humans. Steam power used the coal trust fund (and later, oil) to fundamentally speed up human events and decouple them from the constraints of limited forms of energy such as the wind or human muscles. Blitzkrieg allowed armies to roar ahead at 30-40 miles per hour instead of marching at 5 miles per hour. Blitzeconomics allowed the global economy to roar ahead at 8% annual growth rates instead of the theoretical 0% average across the world for Mercantilist zero-sum economics. “Progress” had begun.

The equation was simple: energy and ideas turned into products and services could be used to buy time. Specifically, energy and ideas could be used to shrink autonomously-owned individual time and grow a space of corporate-owned time, to be divided between production and consumption. Two phrases were invented to name the phenomenon: productivity meant shrinking autonomously-owned time. Increased standard of living through time-savingdevices became code for the fact that the “freed up” time through “labor saving” devices was actually the de facto property of corporations. It was a Faustian bargain.

Many people misunderstood the fundamental nature of Schumpeterian growth as being fueled by ideas rather than time. Ideas fueled by energy can free up time which can then partly be used to create more ideas to free up more time. It is a positive feedback cycle, but with a limit. The fundamental scarce resource is time. There is only one Earth worth of space to colonize. Only one fossil-fuel store of energy to dig out. Only 24 hours per person per day to turn into capitive attention.

Among the people who got it wrong was my favorite visionary, Vannevar Bush, who talked ofscience: the endless frontier. To believe that there is an arguably limitless supply of valuable ideas waiting to be discovered is one thing. To argue that they constitute a limitless reserve of value for Schumpeterian growth to deliver is to misunderstand how ideas work: they are only valuable if attention is efficiently directed to the right places to discover them and energy is used to turn them into businesses, and Arthur-Clarke magic.

It is fairly obvious that Schumpeterian growth has been fueled so far by reserves of fossil fuels. It is less obvious that it is also fueled by reserves of collectively-managed attention.

For two centuries, we burned coal and oil without a thought. Then suddenly, around 1980, Peak Oil seemed to loom menacingly closer.

For the same two centuries it seemed like time/attention reserves could be endlessly mined. New pockets of attention could always be discovered, colonized and turned into wealth.

Then the Internet happened, and we discovered the ability to mine time as fast as it could be discovered in hidden pockets of attention. And we discovered limits.

And suddenly a new peak started to loom: Peak Attention.

Date: 2014-12-29; view: 1125

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| The Smithian/Schumpeterian Divide | | | III. Coasean Growth and the Perspective Economy |