CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Nuclear terrorism. New threats

The very existence of nuclear weapons and their production endanger our safety because they are susceptible to terrorist exploitation. Nuclear weapons and production sites all over the world are vulnerable to terrorist attack or to theft of weapons or weapons-grade materials. Russia, due to the breakup of the former Soviet Union, has a weakened command and control system, making their substantial arsenal especially vulnerable to terrorists. In addition, nuclear weapons are not helpful in defending against or responding to terrorism because nuclear weapons cannot target a group that is unlocatable.

Many people believe that nuclear weapons are well protected and that the likelihood of terrorists obtaining these weapons is low. In the aftermath of the Cold War, however, the ability of the Russians to protect their nuclear forces has declined precipitously. In addition, a coup in a country with nuclear weapons, such as Pakistan, could lead to a government coming to power that was willing to provide nuclear weapons to terrorists. In general, the more nuclear weapons there are in the world and the more nuclear weapons proliferate to additional countries, the greater the possibility that nuclear weapons will end up in the hands of terrorists. The best remedy for keeping nuclear weapons out of the hands of terrorists is to drastically reduce their numbers and institute strict international inspections and controls on all nuclear weapons and weapons-grade nuclear materials in all countries, until these weapons and the materials for making them can be eliminated.

In light of the Cold War’s end, many people believed that nuclear threats had gone away. While the nature of nuclear threats has changed since the end of the Cold War, these threats are far from having disappeared or even significantly diminished. During the Cold War, the greatest threat was that of a massive nuclear exchange between the United States and Soviet Union. In the aftermath of the Cold War, a variety of new nuclear threats have emerged. Among these are the following dangers:

1. Increased possibilities of nuclear weapons falling into the hands of terrorists who would not hesitate to use them

2. Nuclear war between India and Pakistan

3. Policies of the US government to make nuclear weapons smaller and more usable

4. Use of nuclear weapons by accident, particularly by Russia, which has a substantially weakened early warning system

5. Spread of nuclear weapons to other states, such as North Korea, that may perceive them to be an “equalizer” against a more powerful state

7. Nuclear-weapon-free zones

The concept of nuclear-weapon-free zones (NWFZs) in populated parts of the globe (as distinct from uninhabited areas, such as the Antarctic) was devised primarily to prevent the emergence of new nuclear-weapon states. To the extent that the incentive to acquire nuclear weapons may emerge from regional security considerations, the establishment of such zones strengthens the cause of nuclear non-proliferation.

NWFZs have come to be recognized by the international community as a part of a phased approach to the process of nuclear arms control and disarmament. In this regard, the four existing NWFZ arrangements have a number of common characteristics:

1) a legal obligation to place all nuclear material and installations under full-scope IAEA safeguards;

2) to clearly demarcate the geographic limits of the zone of application in the territories of member states;

3) to specify the obligations, rights and responsibilities of contracting and protocol parties;

4) to promote international cooperation in the peaceful applications of nuclear energy under safeguards;

5) to give indefinite duration to the NWFZ treaties. In contrast to the NPT, NWFZs do not permit the "stationing" of nuclear weapons on the territories of states parties or "nuclear sharing" arrangements among nuclear-weapon and non-nuclear-weapon states. Currently, more than 100 non-nuclear-weapon states (NNWS) are parties to NWFZ treaties.

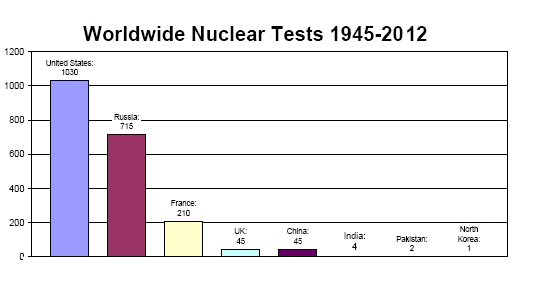

World's nuclear weapon

Nuclear-weapon-free zones

Conclusion

Today, the gravest threat comes from the possibility of terrorists acquiring the nuclear weapons. This threat is compounded by the dangers of nuclear proliferation, as more and more countries hedge against potentially negative in their regions by acquiring the wherewithal to build the bomb. Then there is the increasing global demand for nuclear energy, which will spread the infrastructure necessary to produce fissile nuclear materials still wider. The world, in short, is on the verge of entering an age of more nuclear weapons states, more nuclear materials, and more nuclear facilities that are poorly secured—making the job of the terrorists seeking the bomb easier and the odds that a nuclear weapon will be used greater.

Nevertheless, if the world wants to move toward zero nuclear weapons, it must first stop moving in the wrong direction. That means, among other things, halting the further production of fissile materials (plutonium and highly enriched uranium) for nuclear weapons and banning nuclear weapons tests. The international community has long sought to achieve those objectives through the negotiation and entry into force of multilateral treaties: the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty (FMCT) and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). But neither of these efforts has been fully realized.

Putting in place legally binding constraints on fissile material production and nuclear weapons testing must remain a high priority. Most alarmingly, the likelihood that non-state terrorists will get their hands on nuclear weaponry is increasing. In today's war waged on world order by terrorists, nuclear weapons are the ultimate means of mass devastation. And non-state terrorist groups with nuclear weapons are conceptually outside the bounds of a deterrent strategy and present difficult new security challenges.

What should be done? First and foremost is intensive work with leaders of the countries in possession of nuclear weapons to turn the goal of a world without nuclear weapons into a joint enterprise. Nuclear disarmament depends upon cooperation between nations possessing nuclear weapons and those without them.

And this situation cannot be sustained indefinitely. As long as some states have nuclear weapons, others will inevitably aspire to possess them for national security, as status symbols, or for terrorist uses. We must contemplate nuclear weapons issues not just as a state-based interest issue, but rather as an overall issue posed to all of humanity. Only in a world verifiably free of nuclear weapons will there be no proliferation. That will be a safer world and a better world for all — equally.

Date: 2015-12-11; view: 982

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| The Non-proliferation treaty | | | Nová grafika NVIDIA |