CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

What Is Democracy?

CONTENTS

Introduction

Defining Democracy

Rights

The Rule of Law

Elections

The Culture of Democracy

Democratic Government

Politics, Economics, and Pluralism

Editor: Howard Cincotta

Internet Editor/Designer: Barbara Morgan

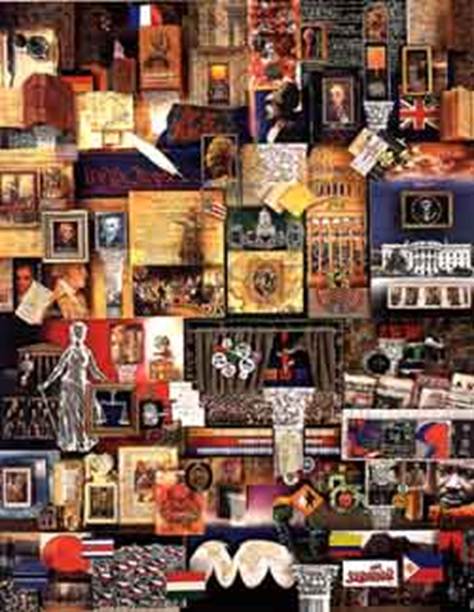

Illustrations: Robert Banks

Photos: Scheré Johnson

The staff is indebted to the following individuals and organizations, whose advice and papers were instrumental in organizing and shaping many of the ideas presented in the text:

Eric Chenoweth

John P. Crisp, Jr.

Matthew Gandal

Chester E. Finn, Jr.

Andrew Forsaith

John O. Frank

Diane Ravitch

Theodore Rebarber

Educational Excellence Network

American Federation of Teachers' Education for Democracy/International

INTRODUCTION

We live in a time when the call for freedom and democracy echoes across the globe. Eastern Europe has cast off the totalitarian governments of almost half a century, and the republics of the former Soviet Union are struggling to replace the Communist regime of almost 75 years with a new democratic order, something they could never before experience. But the drama surrounding the extraordinary political changes in Europe obscures the remarkable degree to which the promise of democracy has mobilized peoples throughout the world. North and South America are now virtually a hemisphere of democracy; Africa is experiencing an unprecedented era of democratic reform; and new, dynamic democracies have taken root in Asia.

This worldwide phenomenon belies the skeptics who have contended that modern liberal democracy is a uniquely Western artifact that can never be successfully replicated in non-Western cultures. In a world where democracy is practiced in nations as different as Japan, Italy, and Venezuela, the institutions of democracy can legitimately claim to address universal human aspirations for freedom and self-government.

Yet freedom's apparent surge during the last decade by no means ensures its ultimate success. Chester E. Finn, Jr., professor of education and public policy at Vanderbilt University and director of the Educational Excellence Network, said in remarks before a group of educators and government officials in Managua, Nicaragua: "That people naturally prefer freedom to oppression can indeed be taken for granted. But that is not the same as saying that democratic political systems can be expected to create and maintain themselves over time. On the contrary. The idea of democracy is durable, but its practice is precarious."

Democratic values may be resurgent today, but viewed over the long course of human history, from the French Revolution at the end of the 18th century to the rise of one-party regimes in the mid-20th century, most democracies have been few and short-lived. This fact is cause for neither pessimism nor despair; instead, it serves as a challenge. While the desire for freedom may be innate, the practice of democracy must be learned. Whether the hinge of history will continue to open the doors of freedom and opportunity depends on the dedication and collective wisdom of the people themselves--not upon any of history's iron laws and certainly not on the imagined benevolence of self- appointed leaders.

Contrary to some perceptions, a healthy democratic society is not simply an arena in which individuals pursue their own personal goals. Democracies flourish when they are tended by citizens willing to use their hard-won freedom to participate in the life of their society--adding their voices to the public debate, electing representatives who are held accountable for their actions, and accepting the need for tolerance and compromise in public life. The citizens of a democracy enjoy the right of individual freedom, but they also share the responsibility of joining with others to shape a future that will continue to embrace the fundamental values of freedom and self-government.

Date: 2015-04-20; view: 1512

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| A. AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT | | | DEFINING DEMOCRACY |