CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

The Sanctity of Private Property

A Match the captions (1-4) with the pictures (a-d).

1.In education, computers can make all the difference____________

2.Using a cashpoint, or ATM________________

3.The Internet in your pocket_____________

4.Controlling air traffic______________

B How are computers used in the situations above? In pairs, discuss your ideas.

C Computers are everywhere nowadays. Here is the text about some of their possible uses. Read the text and check your answers to B.

Text C. THE DIGITAL AGE

We are now living in what some people call the digital age, meaning that computers have become an essential part of our lives. Young people who have grown up with PCs and mobile phones are often called the digital generation. Computers help students to perform mathematical operations and improve their maths skills. They are used to access the Internet, to do basic research and to communicate with other students around the world.

Teachers use projectors and interactive whiteboards to give presentations and teach sciences, history or language courses. PCs are also used for administrative purposes – schools use word processors to write letters, and databases to keep records of students and teachers. A school website allows teachers to publish exercises for students to complete online.

Students can also enrol for courses via the website and parents can download official reports.

Mobiles let you make voice calls, send texts, email people and download logos, ringtones or games. With a built-in camera you can send pictures and make video calls in face-to-face mode. New smartphones combine a telephone with web access, video, a games console, an MP3 player, a personal digital assistant (PDA) and a GPS navigation system, all in one.

In banks, computers store information about the money held by each customer and enable staff to access large databases and to carry out financial transactions at high speed. They also control the cashpoints, or ATMs (automatic teller machines), which dispense money to customers by the use of a PIN-protected card. People use a Chip and PIN card to pay for goods and services. Instead of using a signature to verify payments, customers are asked to enter a four-digit personal identification number (PIN), the same number used at cashpoints; this system makes transactions more secure. With online banking, clients can easily pay bills and transfer money from the comfort of their homes.

Airline pilots use computers to help them control the plane. For example, monitors display data about fuel consumption and weather conditions. In airport control towers, computers are used to manage radar systems and regulate air traffic. On the ground, airlines are connected to travel agencies by computer.

Travel agents use computers to find out about the availability of flights, prices, times, stopovers and many other details.

D When you read a text, you will often see a new word that you don't recognize. If you can identify what type of word it is (noun, verb, adjective, etc.) it can help you guess the meaning.

Find the words (1-10) in the text above. Can you guess the meaning from context? Are they nouns, verbs, adjectives or adverbs? Write n, v, adj or adv next to each word.

| 1. perform __________ 2. word processor __________ 3. online __________ 4. download __________ 5. built-in __________ | 6. digital __________ 7. store __________ 8. financial __________ 9. monitor __________ 10. data __________ |

E Match the words in D (1 -10) with the correct meanings (a-j).

| a) keep, save b) execute, do. c) monetary d) screen e) integrated | f) connected to the Internet.. g) collection of facts or figures. h) describes information that is recorded or broadcast using computers i) program used for text manipulation.. j) copy files from a server to your PC or mobile |

F Now find the words in the text and match them with the meanings below.

| a. information ______ b. execute (do) ______ c. connected with money ______ d. keep (save) ______ e. massive ______ f. linked ______ | g. self-acting, mechanical ______ h. screen ______ i. powerful computer usually connected to a network ______ j. program used for text manipulation ______ |

G In pairs, discuss these questions.

1.How are/were computers used in your school?

2.How do you think computers will be used in school in the future?

3. Language work: Articles (revisions)

Study these nouns.

a supermarket technology a computer money

Supermarket and computer are countable nouns.

We say a supermarket and supermarkets. Technology and money are uncountable nouns. They have no plural and you cannot use them with a or an.

Study this paragraph.

Computers have many uses. In shops a computer scans the price of each item. Then the computer calculates the total cost of all the items.

We use a plural noun with no article, or an uncountable noun, when we talk about things in general.

Computers have many uses.

Information technology is popular.

We use a/an when we mention a countable noun for the first time.

In shops a computer scans the price of each item.

When we mention the same noun again, we use the.

The computer calculates the total cost.

We use the with countable and uncountable nouns to refer to specific things.

The price of each item.

The total cost of all the items.

The speed of this computer.

A Here are some common nouns in computing. With the help of the dictionary divide them into countable and uncountable nouns. In most dictionaries nouns are marked C for countable and U for uncountable.

1. capacity 2. memory 3. drive 4. data 5. monitor 6. speed 7. device 8. mouse 9. port 10. disk 11. software 12. modem

B Complete these texts with a/an, the (or nothing at all) as necessary.

The Walsh family have (1) ______ computer at home. Their son uses (2) ______ computer to help with (3) ______ homework and to play (4) ______ computer games. Their student daughter uses (5) ______ computer for (6) ______ projects and for (7) ______ email. All (8) ______ family use it to get (9) ______ information from (10) ______ Internet.

I use (1)______ computers to find information for (2)______ people. Readers come in with a lot of queries and I use either our own database or (3)______ national database that we’re connected to to find what they want. They might want to know (4) ______ name and address of (5) ______ particular society, or last year’s accounts of a company and we can find that out for them. Or they might want to find (6)______ particular newspaper article but they don’t know (7) ______exact date it was published so we can find it for them by checking on our online database for anything they can remember: (8) ______ name or the general topic. And we use (9) ______ computers to catalogue (10) ______ books in (11) ______ library and to record (12) ______ books that (13) ______ readers borrow.

Language work: collocations 1

C Look at the HELP BOX and then match the verbs (1-5) with the nouns (a-e) to make collocations from the text on pages 2-3.

| 1. give 2. keep 3. access 4. enter 5. transfer | a) money b) a PIN c) databases d) presentations e) records | HELP BOX Collocations 1 Verbs and nouns often go together in English to make set phrases, for example access the Internet. These word combinations are called collocations, and they are very common. Learning collocations instead of individual words can help you remember which verb to use with which noun. Here are some examples from the text on pages 2-3: perform operations, do research, make calls, send texts, display data, write letters, store information, complete exercises, carry out transactions. |

D Use collocations from A and the HELP BOX to complete these sentences.

1. Thanks to Wi-Fi, it's now easy to __________________ from cafes, hotels, parks and many other public places.

2. Online banking lets you __________________between your accounts easily and securely.

3. Skype is a technology that enables users to __________________ over the Internet for free.

4. In many universities, students are encouraged to __________________ using PowerPoint in order to make their talks more visually attractive.

5. The Web has revolutionized the way people __________________ with sites such as Google and Wikipedia, you can find the information you need in seconds.

6. Cookies allow a website to __________________ on a user's machine and later retrieve it; when you visit the website again, it remembers your preferences.

7. With the latest mobile phones, you can __________________ with multimedia attachments – pictures, audio, even video.

Language work: Past Simple – Present Perfect (revision)

E The artist is being interviewed. Make questions to match his answers. Use the correct form of the Past simple or Present perfect, whichever is correct. For example:

Question: What did you do yesterday'?

Answer: Worked on the computer.

| 1. Q What... A Worked on a CD of my paintings. 2. Q How many... A About a third. 3. Q What... A I destroyed them. 4. Q How... A I scanned them in. 5. Q How... A I've organised them into themes. | 6. Q Have... A Yes, I've added a sound track. 7. Q How long... A It's taken me about a week. 8. Q When... A I started about ten years ago. 9. Q What... A Before I had a computer, I had to use slides. 10. Q Have... A Yes, I've sold a few. |

F Put the tenses in this dialogue in the correct form: Past simple or Present perfect.

A What (do) today?

B I (work) on my project. I (search) the Web for sites on digital cameras.

A (find) any good ones?

B I (find) several company sites - Sony, Canon,... but I (want) one which (compare) all the models.

A Which search engine (use)?

B Dogpile mostly, (ever use) it?

A Yes, I (try) it but I (have) more luck with Ask Jeeves. Why don't you try it?

B I (have) enough for one night. I (spend) hours on that project.

A I (not start) on mine yet.

B Yeh? I bet you (do) it all.

4. Computers at work

A Listen to four people talking about how they use computers at work. Write each speaker's job in the table.

electrical engineer secretary librarian composer

| Speaker | Job | What they use computers for? |

B Listen again and write what each speaker uses their computer for.

5. Computer Users

A How do you think these professions might use computers? Compare answers with others in your group.

Architects, interior designers, farmers, landscape gardeners, musicians, rally drivers, sales people

B Work in pairs. Find out this information from your partner. Make sure you use the correct tense in your questions. For example:

download music from the Internet [what site]

A Have you ever downloaded music from the Internet?

B What site did you use?

1.send a video email attachment [who to, when]

2.fit an expansion card [which type]

3.replace a hard disk [what model]

4.fix a printer fault [what kind]

5.make your own website [how]

6.have a virus [which virus]

7.watched TV on the Internet [which station]

8.write a program [which language]

C Describe how you use computers in your study and in your free time.

6. Other applications

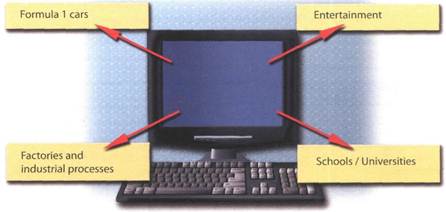

A In small groups, choose one of the areas in the diagram below and discuss what you can do with computers in that area. Look at the Useful language box below to help you.

|

USEFUL LANGUAGE:

Formula 1 cars: design and build the car, test virtual models, control electronic components, monitor engine speed, store (vital) information, display data, analyse and communicate data

Entertainment: download music, burn CDs, play games, take photos, edit photos, make video clips, watch movies on a DVD player, watch TV on the computer, listen to MP3s, listen to the radio via the Web

Factories and industrial processes: design products, do calculations, control industrial robots, control assembly lines, keep record of stocks (materials and equipment)

School/University: access the Internet, enrol online, search the Web, prepare exams, write documents, complete exercises online, do research, prepare presentations

Computers are used to...

A PC can also be used for...

People use computers to ...

B Write a short presentation summarizing your discussion. Then ask one person from your group to give a summary of the group's ideas to the rest of the class.

C. Write a list of as many uses of the computer, or computer applications, as you can think of.

D Now read the text below and underline any applications that are not in your list.

What can computers do?

Computers and microchips have become part of our everyday lives: we visit shops and offices which have been designed with the help of computers, we read magazines which have been produced on computer, we pay bills prepared by computers. Just picking up a telephone and dialing a number involves the use of a sophisticated computer system, as does making a flight reservation or bank transaction.

We encounter daily many computers that spring to life the instant they’re switched on (e.g. calculators, the car’s electronic ignition, the timer in the microwave, or the programmer inside the TV set), all of which use chip technology.

What makes your computer such a miraculous device? Each time you turn it on, it is a tabula rasa that, with appropriate hardware and software, is capable of doing anything you ask. It is a calculating machine that speeds up financial calculations. It is an electronic filing cabinet which manages large collections of data such as customers’ lists, accounts, or inventories. It is a magical typewriter that allows you to type and print any kind of document – letters, memos or legal documents. It is a personal communicator that enables you to interact with other computers and with people around the world. If you like gadgets and electronic entertainment, you can even use your PC to relax with computer games.

The Sanctity of Private Property

by

Anthony M. Ludovici

Heath Cranton Limited

London

1932

- p. v -

Preface

The present little work consists of an address delivered by the author to a meeting of the St. James's Kin of the English Mistery on November 10th, 1931. In view of the interest which, in these days of high taxation and Communistic propaganda, attaches to the problem of private property, the members of the English Mistery, as also the author, hoped that a wider public might be glad of this concise discussion of the subject, and it was therefore decided to issue it in book form.

The right of private property and the question of its sanctity or profanity have so long been debated by the two opposing schools of Capitalism and Communism, and every term and position in the controversy is now so deeply infected with prejudice, that a brief and impartial review of the history and philosophy of the subject, together with a suggested solution of the problem of proprietary rights, based neither on the Capitalist nor on the Communist standpoint, cannot, it is thought, fail to be of help, if only as a starting point for the reader's own speculations.

- p. 7 -

The Sanctity of Private Property

1. It would be impossible in the limited space at my disposal to give an adequate idea of the confusion that prevails in modern thought, modern historical interpretation and modern anthropological theories, regarding the institution of private property.

Suffice it to say that, in the course of their enquiry into this institution, economists and scholars always claim the scientific method as the justification for their conclusions, and that this method is almost as frequently abused, feigned, or neglected. A mass of literature has been published on the subject, and three-quarters of it consists merely of preconceptions and prejudice. The anxiety to establish the institution of private property upon the solid foundation of a first principle of life or human nature, upon a natural or divine law, or even upon irrefutable data concerning origins, has led most investigators astray, and made them forget that human institutions are all ultimately derived from human taste and selection, and that as a rule their credit endures only so long as the taste of their founders is shared or at least approximately equalled by posterity.

2. To deal with the anthropological theories first, we may, for the sake of brevity, divide them into two, as belonging respectively to the principal hostile scientific camps — the theory of those who argue from their study of primitive races that all property was originally communal, and the theory of those who,

- p. 8 -

arguing from more or less the same data, claim, on the contrary, that all property was originally private. The first regard communism as natural, and private ownership as a subsequent corruption, while the latter regard the converse as true.

These enquiries of the anthropologists regarding the question of property have been pursued in accordance with a method that has crept into the science of economics and sociology, and which consists in the practice of seeking the raison d'être, and the soundness of modern political or social institutions, or sometimes even the warrant for them, in the habits, traditions and ceremonies of savages. It is as if the motive behind such a method were the conviction that whenever an institution can be found to exist among men in a state of nature, it must possess some extraordinary quality compelling respect and consideration. It is really an effort along the lines of evolutionary sociology, having for its object the establishment of modern sociological principles and laws upon the logic of unsophisticated humanity surviving in the heart of nature. It is, however, a romantic or sentimental method of procedure; for interesting as the habits and ceremonies of savages may be in themselves, they cannot be very helpful to us as guides in the criticism or elaboration of the rules governing our own society, nor can they tell us much concerning its evolution.

Nevertheless, countless volumes have been written and are still being written along these lines. We are surfeited with facts concerning primitive marriage, primitive religion and primitive morality. But, for our present purpose at least, it is necessary to record only one achievement that has resulted from all this labour, which is that both of the old rival schools of anthropology — that which regarded communal possession and that which regarded private ownership as the original institutions of mankind — have been proved

- p. 9 -

equally wrong. For the correct verdict turns out to be that the blend of communal with individual ownership is characteristic of all primitive society and "no irrational, undifferentiated absorption of the individual in the group can be discovered."

Naturally the Communists, men like Engels and Marx, seized upon the evidence in favour of communal possessions in primitive societies, in order to support their own political aims, while those in favour of a capitalistic order made an equally one-sided use of the other evidence. But even if one of these — say the Communists — had found communal possession universally established among existing primitive races (W. H. R. Rivers on purely scientific grounds actually championed the view that communal ownership was the primitive form), or among past primitive races, what would this have proved in favour of establishing the same order at the present time?

Surely it must soon become evident to our learned sociologists and economists that the attempt to explain, illustrate, or support our own civilized institutions by a study of the institutions of existing or past primitive peoples, cannot fail, quite apart from the sentimental bias behind it, to prove the sorriest waste of useful energy, because it is always open to the sceptic to ask whether the fact that these existing primitive peoples have remained at the bottom of the hierarchy of races may not be due to the very institutions which we study with so much reverence and humility. In any case, the attempt to base upon such anthropological data any rule for the observance of modern mankind, or any first principle on which to build a system, must be unscientific, because, at best, these data cannot tell more than an incomplete story — the story of the most backward peoples. They must omit the very earliest history of those races whom we have known or can know only as civilized or half-civilized.

- p. 10 -

To those whom it may interest, however, let the fact be known for what it is worth, that nowhere in existing primitive races, or among past primitive races, has communal possession been found to exist unblended with private ownership or vice versa.

3. Turning now to the philosophers and their work on the problem of private property, we encounter much the same striving as among the anthropologists, though with this difference — that while the latter sought their authority or basis for one form or the other of ownership in the customs of primitive man, the former seek for a fundamental law, or an a priori and self-evident principle, inherent in humanity or human society in general, which makes either communal possession or private ownership appear to be sacrosanct, or natural and proper to the animal man.

Regarding at least the early philosophers and legislators, a word of warning seems to be necessary. Because Europe has been very deeply influenced by them it is always well to bear in mind, if we can, that, after all, they were first and foremost townsmen. They had the urban mind, the urban attitude to all things. Their thought and speculations on this matter of property fit very much more perfectly the England of to-day than the England of yesterday. In fact, quite apart from the problem of property, the modern world may never fully understand how much of its tendency to develop and multiply large urban centres to the sacrifice of everything else, may not in part be due to the circumstance that, from the very start, European thought was the thought of men born and bred in city states. This has tinctured the whole of our philosophy. Could it possibly have failed to be translated into action?

When Maine said, "It is . . . Roman jurisprudence which, transformed by the theory of Natural Law,

- p. 11 -

has bequeathed to the moderns the impression that individual ownership is the normal state of proprietary right," he had this important fact in mind. At all events, the urban life of the thinkers and lawyers of Athens, Sparta and Rome, is more than usually apparent in their treatment of our problem, and we might say with justice that it was among these men that the notion that the ownership of all things might be absolute first occurred to the Western World.

And this is more or less comprehensible. For what a townsman handles, what he is accustomed to hold as his own, is chiefly the kind of property which may form the object of unconditional or unlimited ownership, or ownership divorced from duties — the kind of property which English law terms "choses in possession," such as cattle, clothes, coin, house furniture, carriages, etc., and of which English law precisely states that they "are the objects of absolute ownership, that is, of a right of exclusive enjoyment, mainly including the right to maintain or recover possession of the things against or from all persons, and further comprehending the right of free use, alteration, or destruction [this last is important as divorcing the owner of the object entirely from any duty of obligation to others in connexion with his ownership] and the right of free alienation, with the corresponding liability to alienation for debt." 1

Now I suggest that it was natural for townsmen, for men bred in city states, to develop this idea of property, because this was the kind of property with which they were chiefly concerned. They knew little of any other kind. 2 Had they known more, they would probably have felt less inclined to extend

1 J. Williams: Principles of the Law of Personal Property.

2 This, on the whole, is more true of the modern Western European townsman than of the townsman of Athens or Rome; but its partial truth even in regard to the latter, is an important factor, which is too often overlooked.

- p. 12 -

even to this kind of property the idea of freedom from all social duty or obligation. And that is why the history of the law and of the ideas on property, in the ancient world of Greece and Rome, tends to follow this course — gradually to include in the class of things of which absolute ownership is normal and possible to the townsman — clothes, trinkets, furniture, ornaments — those things of which ownership divorced from duty is not, or should not be possible, either to the townsman or anyone else — the land, the rivers, the lakes, great riches beyond a man's physical needs, etc.

Thus Maine is able to say with good reason that the history of Roman Property Law is the history of the assimilation of Res mancipi to Res nec mancipi, or of things which require a mancipation to things which do not require it.

But this is also the history of English and French Law. Things which could not without danger become objects of absolute ownership, that is to say free from all social duties and obligations, like land and riches beyond the individual's physical and professional needs, have, through the influence of the urban mind, first of Greece and Rome, and finally of London and Paris, working at the same problem, become entirely emancipated. But whether London and Paris would ever have arrived so quickly at the idea of absolute ownership in all things, without the antecedent influence of Greece and Rome, it is impossible to say. I venture to doubt it. In any case, France was a little slower than England; for whereas France, a country which might be supposed to have been more influenced by Roman Law, recognized rights of absolute ownership in all things only at the time of the Revolution in 1793, 1 individual ownership in

1 I am not, of course, including the period previous to the Barbarian Invasion, in which, as is well known, the ownership of the land had become free and personal in Gaul under Roman rule.

- p. 13 -

all things divorced from duties and obligations was finally made possible in England at the close of the Puritans' all too lengthy spell of power in 1660.

When, therefore, we study the philosophers on this question of private property, it is well to remember the biassed beginnings of thought on property in Europe, and to bear in mind through what influence the impression arose that absolute individual ownership is the normal state of proprietary right.

At all events, it may be admitted at once that, although the right of private property has been advocated and defended by Western European philosophers and lawyers from the dawn of history as something self-evident, not one has ever succeeded in establishing it on a fundamental law or principle of life, morality or logic, while the attempt to do the same for communal ownership has been even more hopeless.

There is no a priori truth, no self-evident principle from which the right of private property can be derived.

But of the various attempts to derive it in this manner, I may mention the claims of:—

(a) Those who argue that occupation is the origin of private property. Among these are the Roman lawyers, and thinkers like Kant, Thiers, Lewinski (the latter writing against Maine), and St. Thomas Aquinas.

(b) Those who point to work or labour as the origin or sanctification of private property. Foremost among these is Locke and through him the economists Adam Smith, Ricardo, Say; the Communists, Engels, Karl Marx, Lassalle, Lenin, Stalin, etc. Spencer and Mill also to some extent held and supported Locke's view, but with as little intention as Locke himself had of giving arguments to the Communists.

(c) Those who set up the idea of contract as the origin of private property. Among these are Hobbes and his followers, including Rousseau and his followers,

- p. 14 -

together with men like Grotius, Pufendorf, etc. Hume with his idea of an original "convention" belongs to this group, as does also Kant.

(d) Those who say that law creates private property. Among these, who here and there necessarily merge into the preceding group, are St. Augustine, Bossuet, Mirabeau, Tronchet, Robespierre, Montesquieu, Trendelenburg, Hume, Wagner, Kant, Bentham.

(e) Those who say that the nature of man makes it necessary and useful. Among these are Roscher, Bentham, Mill — in fact all the Utilitarians. Hume can be included in this group also. His discussion of the subject, although it reveals, here and there, startling instances of shallowness, is nevertheless very searching and reasonable.

(f) Those who claim it as a natural human right. Among these are Blackstone (to some extent the Roman lawyers and the Catholic Church), Fichte, Portalis, Professor Ahrens, Daloz, Laveleye, and Herbert Spencer, who, like Kant, bases it on what he calls "the law of equal freedom." There is, however, no reason to suppose that Spencer was inspired by Kant. Schiller was also one of these with his:—

| "Etwas muss er sein eigen nennen, Oder der Mensch wird morden und brennen." (Wallensetin's Lager, xi) |

None of these thinkers, however, except the Utilitarians and those who see in law and expediency a warrant for private property, makes a very good case. Most of them, including Locke and his followers, who rest proprietary rights on labour, end in absurdity, and we find ourselves forced to the conclusion that just as "private property has meant an immense number of different things at different times and places," so there are as many solutions of the problem

- p. 15 -

of property as there are kinds of civilization. According to the end we wish to achieve with man and society, according to the degree of permanence we wish to secure, so shall we determine the kind of proprietary rights which it is expedient to grant to individuals, and the establishment of such rights is a matter of taste, custom and law. But, in exercising taste and judgment in this undertaking, it is as well to bear constantly in mind that we are children of a long line of people — a line stretching across two millenniums — who, more or less gratuitously, have taken individual proprietary rights as self-evident; that, moreover, as we have seen, the thinkers along this line have been more concerend about finding a fundamental principle to explain the self-evidence and inviolability of individual proprietary rights than about justifying them, and that in justifying them — and justified they must be — presentday thinkers are to some extent treading absolutely virgin soil.

I have said that it was through no accident that the classical thinkers and lawyers should gradually have extended the notion of absolute private ownership (dominium) to all things, even to those things which in their earlier history had allowed only of the notion of limited, conditional, or usufructuary possession (possessio). They were townsmen, accustomed to the baubles which a man can hold without having to give an account of them to anyone.

But there was perhaps less readiness to grant or admit absolute individual ownership in Greece than in Rome. The compulsory readjustments of wealth and property in ancient Greece — readjustments which, unlike the Agrarian Laws of the Gracchi, were successfully maintained — point to this, as do also the innumerable public services which the wealthy were called upon and expected to perform. It is perfectly true that the wealthy Romans also performed public services; but these appear to have been more volun-

- p. l6 -

tary than those of the Greeks, and more regularly prompted by mere ostentation, while it should always be remembered that they were most conspicuous at a time when Roman citizens were entirely free from direct taxation (167 B.C. to A.D. 284), a freedom never enjoyed in Athens to the same extent. On the whole, the general impression obtained from a comparison of the two civilizations is that private wealth in Greece was regarded as very much more dutiable and accessible to the public than it was in Rome. Perhaps this may explain why, in Aristotle, we find a recommendation regarding wealth which reveals a point of view very much wiser than the later Roman conception of free individual ownership.

In the Politics, Aristotle defends private ownership as being economically superior (because all men regard more what is their own than what others share with them in, to which they pay less attention than is incumbent on everyone); as being a source of pleasure (for it is unspeakable how advantageous it is that a man should think he has something which he may call his own. . . . Besides, it is very pleasing to us to oblige and assist our friends and companions, etc.); and as being more conducive to the development of character (for restraint and liberality are made possible by it). But he insists repeatedly on the desirability of blending private and communal ownership. "It is evident then," he concludes, "that it is best to have property private, but to make the use of it common." There is no explicit statement that private property when it exceeds certain limits involves certain duties and obligations, but this meaning can be read into Aristotle's words without difficulty. There was in Rome little of the feeling that is consonant with this view of property, and that is probably why Christianity found such a favourable environment for its teaching in the Roman

- p. 17 -

Empire. The revolt against riches which was already discernible in Stoicism, and forms so prominent a part of Christian doctrine and the writings of the early Christian Fathers, was no doubt stimulated by the rigour of the Roman conception of absolute private ownership in a way in which it would never have been stimulated by the Greek attitude.

Thought in Europe on the problem of property thus became absorbed in a negative or hostile attitude to riches as such, before it had had the time or the opportunity to develop Aristotle's more balanced view. To early Christianity the institution of private property was not merely unwise, it was actually sinful, and was classed among the many evil and inevitable consequences of the Fall. Not only did the early Fathers of the Church regard Communism as the original state of innocent and blissful mankind, but, as we know, in the early years of the Church, Christians also practised and advocated Communism. Charity was not the duty of giving, it was the duty of restoring to the destitute that which was their own. It was not an act of mercy, but an act of simple justice. St. Thomas Aquinas actually advocated robbery as a means of relieving destitution. St. Gregory said, when we give to the poor we render to them that which is their own, we do not give what is ours. Now although, side by side with these dubious exhortations to charity, private property was explicitly declared to be a necessary though regrettable consequence of our fallen condition, nobody can deny that from St. Gregory's inflammatory utterance to Lenin's cry to the people of St. Petersburg in April, 1917, "Rob back that which has been robbed," is not a very great step.

And it is significant that this cry of Lenin's also came after a long spell of the rigorous observance of private ownership in the most absolute and irresponsible sense.

- p. 18 -

The compromise between the Roman idea of private proprietary rights in the sense of dominium, and the claims of Christianity, resulted, of course, in charity; and, apart from the spontaneous growth of Feudalism in Europe, the origin of which no one precisely knows, and the original designers of which nobody can name, there has been no attempt since Aristotle first stated the principle, of even thinking out any practical means, any social structure, through which the advantages of private property might be preserved while its asperities and gross abuses were mitigated.

Was it perhaps this thought that caused J. S. Mill to remark: "The principle of private property has never yet had a fair trial in any country; and less so, perhaps, in this country than in some others"? If, by this, Mill meant that the institution of private property has never yet been protected against itself, he means what I do.

Nor is it any good now, at this late hour, to follow the philosophic method and try to convince mankind afresh along logical and self-evident lines, of the desirability of either private property or Communism. For, unless we are prepared to evolve a system based on Aristotle's principle, by which the right of private property can be re-wedded to function and duty, and freed from its present irresponsibility and consequent abuses, unless we can contrive a method by which property can be enjoyed jointly only in so far as it does not destroy freedom and character, and privately only in so far as it expresses and preserves both (and such a system was Feudalism), we shall merely be wasting our time and hastening the disintegration that threatens.

On the whole, then, it may be said that there is little that has been heard since Aristotle which improves on his position or which adds to it, and we can pass over the thinkers and philosophers and turn to history.

- p. 19 -

4. The historical method of enquiry into the problem of private property is certainly more helpful than the philosophic method, and it is one expressly advocated by Aristotle. For although we may be seeking for no canon, and are not prepared, like many modern sociologists, to accept as sacrosanct or respectable that which primitive people or early societies of mankind have practised, we may, nevertheless, feel sure that the study of history will at least enable us to see the different institutions of civilized mankind in the process of working, and to judge of their viability and worth by the extent of their endurance and the kind of people and culture with which they were associated.

But, again, in the work of the historians, it is difficult to escape preconceptions, prejudice and deliberate misrepresentation, and the enquiry has to be prosecuted with consistent scepticism.

Who, for instance, after reading the Whig histories with which alone we have been provided for generations in this country, would ever have imagined that the Puritans, those austere moralists of the seventeenth century, those scholars of Old Testament lore, and critics of Charles I's finance, sense of honour, and "oppressive" notions of rule, were the men who, following Calvin, rejected the Canon Law against usury, and were most eager to be "freed from the efforts of the King's council to bring home to the employing and mercantile classes their duty to the community?" 1 But such is indeed the fact.

Who, after reading the histories, both English and French, of the French Revolution, would ever suspect that this event in France stripped the peasant of his rights of common, and other secular rights of equal importance, and delivered him up defenceless into the

Date: 2014-12-28; view: 2010

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| The digital age | | | Archdeacon Cunningham: The Moral Witness of the Church on the Investment of Money, pp. 25, 26. |